|

Dhinagar S.

Vishnu Bhat B.

Verma S.*

Balakrishnan *

From the Departments of Pediatrics and Pathology*, JIPMER, Pondicherry 605 006, India.

Reprint requests: Dr. Vishnu Bhat, Professor of Pediatrics and In-charge of Neonatology

Division, JIPMER, Pondicherry 605 006, India.

Manuscript Received: December 24, 1997; Initial review completed: February 26,1998; Revision Accepted: April 23, 1998

Aplasia cutis congenita is characterized by sharply demarcated areas of absent skin. Nine forms have been described by Frieden(1). Aplasia cutis involving trunk and extremities in association with Epidermolysis bullosa is extremely rare-(2-5). We describe a neonate with this uncommon disease associated with other anomalies.

Case Report

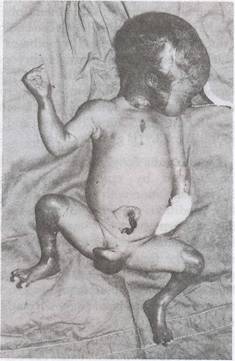

A preterm male baby weighing 2 kg was born at 36 weeks of gestation to a third gravida mother with previous history of one abortion and a stillbirth. The father was mother's first cousin and the antenatal period was uneventful. He was delivered by vaginal route and had Apgar scores of 8 and 9 at one and five minutes, respectively. On examination, this preterm baby had respiratory distress. There were multiple well demarcated raw areas showing absence of skin over scalp, extremities and trunk, varying from 2 x 2 to 7 x 8 cm in diameter with no overlying redundant bullae. The palms and soles were spared unlike lesions in congenital syphilis. He had bilateral small dysplastic pinnae, flat nasal bridge, hypoplastic middle toe of right foot and dysplastic finger and toe nails (Fig. 1). The

baby had oral mucosal ulcers and positive Nikolsky's sign. He developed apnea and expired after 24 hours. The blood VORL on mother and baby were nonreactive. There was no family history of similar lesions.

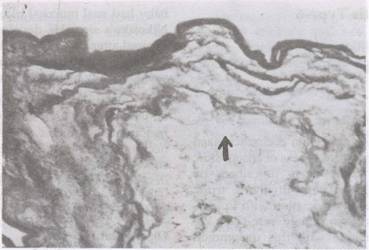

Autopsy revealed ductus arteriosus, fetal lobulation of both kidneys and bilateral mega ureters without ureteric or bladder neck obstruction. Postmortem skin biopsy showed full-thickness absence of skin and dermal appendages in the involved areas, with dermis and epidermis ending abruptly (Fig. 2).

Discussion

Aplasia cutis congenita (ACC) is a rare anomaly characterized by absence of circumscribed areas of skin at birth. The re- ported incidence is one in 10,000 births(6).

|

|

Fig. 1. Clinical photograph showing aplastic lesions over scalp, face and limbs. |

|

|

Fig. 2. Photomicrograph (H&E stain) depicting (arrow) aplastic skin without any appendages. |

It occurs most often sporadically though autosomal recessive and dominant

inheritance have been described(7-9). The etiology is uncertain but suggested

hypotheses include ectodermal arrest during embryogenesis, vascular anomalies in the fetus, intrauterine trauma, amniotic bands and hereditary factors(7,9,10). Frieden has classified aplasia cutis into nine types(8) and its modificatioJ;1(3,9) is given in Table I.

Aplasia cutis congenita (ACC) type-6 is characterized by epidermolysis bullosa (EB) in association with aplasia of skin(3,9). This condition may be associated with other malformations like low set abnormal ears, duodenal atresia, trachea-esophageal fistula, large fontanelle, narrow palpebral fissures, micrognathia,

cleft palate, hypoplasia of nose, joint contractures, rocker bottom feet, genito-urinary malformations, etc.(3,4).

The inheritance is variable depending on the type of EB. Aplasia Cutis (AC) in

association with EB-simplex with mild blistering known as Bart syndrome is inherited

as autosomal dominant and this condition has good prognosis(6). Wojnarowska et al. have described four cases of recessive dystrophic-EB with AC. The healing of aplasia cutis was complete in all cases while EB

remained a problem throughout life with blistering lesions(5). The AC associated with junctional-EB is also transmitted as autosomal recessive without any reported survivors(3).

The present case did not have any bullae at birth but features like dystrophy of nails, positive Nikolsky's sign suggests the diagnosis of epidermolysis bullosa causing intrauterine blistering and a presentation like aplasia cutis(4). This in association with congenital malformations like dysplastic pinnae

and nails, urinary tract anomalies places our case into lethal autosomal recessive form of aplasia cutis Type- 6 (3,9). Although limb anomalies like syn- dactyly, club foot, etc.

have been reported earlier, distal limb reduction as seen in our case has not

been described. The shortening of the middle toe of right foot cannot be explained by EB alone.

TABLE

I-Classification and Salient Features of Aplasia Cutis

|

Type

|

Sites |

Transmission |

Associated malformations |

|

Type 1 |

Scalp |

Autosomal dominant |

Nil |

|

|

(Usually vertex) |

|

|

|

Type 2 |

Scalp |

Autosomal dominant |

Limb reduction anomalies |

|

|

(usually midline) |

|

|

|

. Type 3 |

Scalp |

Sporadic |

Epidermal naevi |

|

|

(asymmetrical) |

|

|

|

Type 4 |

Any |

Sporadic /multifactorial |

Castro intestinal (omphalocele, |

|

|

|

|

gastroschisis), CNS

(encephalocele, spinal |

|

|

|

|

dysraphism,

prosencephaly) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Type 5 |

Limbs / trunk |

Unknown |

Twin pregnancy; Other sibling |

|

|

|

|

usually fetus papyraceous. |

|

Type 6 |

Extremities |

Autosomal recessive |

Duoenal/pyloric atresia |

|

|

|

or |

narrow palpebral fissures, |

|

|

|

dominant |

nasal hypoplasia, low set ears, |

|

|

|

|

micrognathia, syndactyly, |

|

|

|

|

hypoplastic nails, overlapping |

|

|

|

|

of fingers, simian crease. |

|

Type 7 |

Scalp/ |

Sporadic |

Methimazole induced |

|

|

limbs/trunk |

|

|

|

Type 8 |

Linear unilateral |

Sporadic |

Due to herpes/varicella |

|

|

|

|

infection |

|

Type 9 |

Scalp |

Sporadic/ Autosomal |

Trisomy 13,4 p-syndrome |

Since extracellular transudation of embryonic alpha-feto protein usually occurs during the first half of pregnancy, estimation of amniotic fluid alpha-feto protein level may be useful in prenatal diagnosis of aplasia cutis in selected families(4).

The treatment of aplasia cutis depend on the type. If the lesions are small they will heal spontaneously from the margins over a period of time to leave smooth yellowish hairless papery scar. Occasionally hypertrophic

scarring occurs and linear lesions over the limbs may lead to joint contractures. In the majority of simple aplasia cuits,

the prognosis is excellent if attention is paid to the prevention of secondary

infection and further trauma. Sometimes larger defects may need grafting or flap rotation(9). However, cases similar to the present one are uniformally fatal(3).

|

1.

Frieden IJ. Aplasia cutis congenita: A clinical review and proposal for classification. J Am Acad Dermatol 1986; 14: 646- 660.

2.

Bart BJ. Epidermolysis bullosa and congenital localized absence of skin. Arch Dermatol1970; 101: 78-81.

3.

McCarthy MA, Clarke T, Powell FC. Epidermolysis bullosa and aplasia cutis. Int

J

Derm 1991; 30: 481-484.

4.

Carmi R, Sofer S, Karplus M. Aplasia cutis congenita in two sibs discordant for pyloric atresia. Am

J

Med Genetics 1982; 11: 319-328.

5.

Wojnorowska FT, Eady RAJ, Well RS. Dystrophic epidermolysisbullosa presenting with congenital localized absence of skin: Report of four cases. Br

J

Dermatol1983; 108: 477-483.

6.

Bart BJ, Goshin RJ, Anderson VE. Congenital localized absence of skin and associated abnormalities resembling epidermolysis bullosa: Anew syndrome. Arch Dermatol 1966; 93: 296-303.

7.

Levin DL, Nolan KS, Esterly NB. Congenital absence of skin.

J

Am Acad

Dermatol 1980; 2: 203-206.

8.

Bronspiegel N, Zelnick N, Rabinowitz H. Aplasia cutis congenita and intestinal lymphangiectasia: An unusual association. Am J Dis Child 1985;139: 509-513.

9. Atherton DJ, Naewi and other developmetal defects. In: Rook/ Wilkison/Ebling Textbook of Dermatology, Vol. 1 Eds. Champion RH, Burton JL, Ebling FJG. London, Blackweli Scientific Publication, 1992, pp 518-524.

10.

Guillen PS, Pichardo AR, Martinez Fe. Aplasia cutis congenita.

J

Am Acad

Dermatol 1985; 13: 429-433.

|