Prabhjot Mallhi

Pratibha Singhi

From the Department of Pediatrics, Post Graduate Institute for Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh 160012, India.

Reprint requests: Dr. Prahbhjot Malhi, Assistant Professor, Department of Pediatrics, PGIMER, Sector 12, Chandigarh 160012, India.

The importance of early diagnosis and treatment of children with developmental de- lay has emerged in recent years as a matter of growing concern among pediatricians. Early identification of children with delayed development has important implications for their treatment and in preventing risks of future disabilities and secondary problems related to family dysfunction, peer difficulties, and school failure. Successful early identification of delayed development requires that the pediatricians be skilled in the use of screening tests and be aware of the strengths as well as the limitations of developmental screening.

What is Development Screening?

Developmental screening is a brief testing procedure designed to identify children who should receive more intensive diagnosis or assessment(1). Screening refers to the detection of unsuspected deviations from normal development that would not otherwise be identified in routine pediatric practice. The goal of screening is to identify, as early as

possible, developmental disabilities in children at high risk so that

a treatment or remediation can be initiated at an early age when it is

most effective(2-4). Early screening does not merely mean the administration of a single test at one point of time, rather it is a set of processes and procedures used over a period of time(5).

There is a need to distinguish develop- mental screening from

developmental assessment and developmental surveillance. Developmental

assessment refers to a more detailed investigation of developmental

delay and is diagnostic in scope(2,6). On the other hand,

developmental surveillance is a continuous, flexible and comprehensive

process which includes all activities related to the detection of developmental problems and the promotion of development during primary child health care visits. Developmental surveil.1ance includes identification of parental concerns, child observations, screening, immunization and anticipatory guidance(2,7).

Table I lists some of the guidelines re- commended by the Task Force on Screening and Assessment (I).

Approaches to Screening

The three approaches to screening include informal, routine and focussed developmental screening(8).

1. Informal screning is based on observing the child during a routine

pediatric check up and asking parents about their concerns about

child's development. The pediatrician, how- ever, needs to be familiar

with the various developmental milestones at different ages. This is not easy for the general busy practitioner.

Upper limits of normalcy have been used as cut off points to help

identify delay. Such an approach is not a very sensitive way of

screening as it is only useful for not missing major delays in a busy office practice: In addition, several studies report that pediatricians are often inaccurate in their overall estimates of a child's developmental status(9,1O). Almost. half of the children with developmental disabilities are not identified by their pediatricians(11,12). Moreover, parental knowledge of child's development varies greatly and many parents do not appreciate the importance of delay(13). Parents recall of developmental milestones is often inaccurate(l4) and it has been reported that parents tend to overestimate language development and under-rate fine motor skills(15). In light of-these problems, pediatricians may not be able to correctly identify a large majority of children with subtle developmental delays through informal screening methods(6,16).

TABLE I-Guidelines for Screening

1. Screening instruments should be

(I) Reliable and valid

(il) Culturally relevant

(iil) Used only for their specified purpose.

2. Multiple sources of information should be used. 3. Developmental screening should be done only by trained personnel.

4. Screening should be on a recurrent and periodic basis.

5.

.

Family members should be part of the screening

process.

2. Routine formal screening entails systematic developmental screening of

all children with the help of standardized screening instruments. However, such an approach is highly time consuming as it requires large number of trained manpower and may not be warranted given the low incidence of developmental problems among low risk population of children. In our country, as well as in other developing countries, with enormous populations, routine formal screening is neither feasible nor cost effective. Some short screening tests have been developed for use by community health workers(17, 18) but the feasibility, efficacy and cost effectiveness of their use for the entire population is still not known.

Even in the developed countries, the usefulness of routine developmental screening is being questioned. In Sweden where there is an extremely well organized system of screening at child health centers, a recent study has shown that routine examinations at child health centers made a small contribution in the early detection of cerebral palsy(19).

3. Focussed screening involves developmental screening of the following groups of children:

(a) Children whose parents express developmental concerns or in whom teachers and physicians suspect problems.

(b) Newborns with conditions that have known to have high risk for develop- mental delay (Table II).

TABLE II-High Risk Infants Needing Periodic Assessments

Very low birth weight (<1500 g)

Neurologic conditions

Intraventricular hemorrhage Gr. III or IV

Periventricular leukomalacia

Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy

Apgar score 0-3 at 10, 15 and 20 min Meningitis

Persistent seizures

Apnea beyond term

Abnormal neurological condition during first week of life

Hyperbilirubinemia

Symptomatic hypoglycemia with seizures

Septicemia

The concept of "at risk" newborns is being replaced by some authors(20) by the concept of "optimality". Newborns with a low "optimality score" are considered highly likely to develop neuro developmental disabilities later in life. Which 'high risk' newborns require periodic screening ideally needs to be determined locally keeping in mind the feasibility and cost-effectiveness of any neonatal follow-up program. It must, however, be remembered that many babies not considered "at risk" may also manifest developmental problems as they grow. These babies would obviously not be seen during

"at risk" focussed follow up screening.

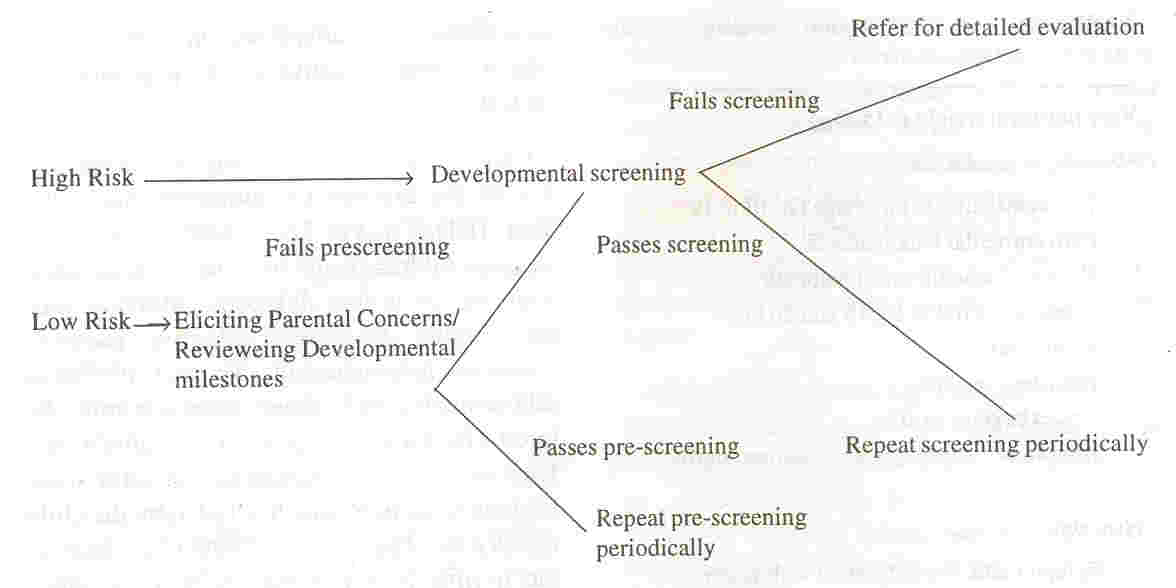

Figure 1 highlights a practical approach

for developmental screening of children.

|

|

Fig. 1 Practical Approach to

Developmental Screening |

Developmental Screening Tests

Several developmental screening tests are available for use in infants and children. There are several well-accepted criteria by which various tests are judged to be appropriate for use in screening programs. It is recommended

that screening test should be simple, brief, convenient to use, cover

all areas of development, have adequate construct validity, be applicable to a wide age range, and have referral criteria that are both specific and sensitive(5,8).

Table III lists some of the commonly used screening tests( 17,18,21-26). It is well to remember that each test has its strength and weaknesses, and the person using it must have an insight into these as well as the correct interpretation of results. It is also important to ensure that the tests have been

developed and standardized on a population which is representative of the population to be tested.

TABLE III

Some Development Screening Tests.

|

Name |

Age |

Domains |

Administration |

Validity |

|

|

range |

evaluated |

time (minutes) |

|

|

Denver Development |

0- 6yr |

Gross Motor, Fine |

20 |

Sensitivity

=

0.13 to 0.46

|

|

Screening Test (DDST)

|

|

Motor, Social, Language, |

|

Specificity = 0.87 to 1.00 |

|

|

|

Self help, Cognitive |

|

|

|

|

Denver II |

0- 6yr |

Gross Motor, Fine |

35 |

NA |

|

|

|

Motor, Social, Language, |

|

|

|

|

|

Self help, Cognitive |

|

|

|

|

Developmental Profile |

0- 91/2 yr Motor, Social, Self help, |

35 |

VC

=

0.52-0.72

|

|

(DP II)

|

|

Cognitive, Language |

|

|

|

|

Cognitive Adaptive Test! |

0- 3yr |

Visual-Motor, Language' |

20 |

Sensitivity

=

0.88

|

|

Clinical Linguistic Auditory

|

|

|

|

|

Specificity

=

0.67

|

|

Milestone Scale |

|

|

|

|

|

|

(CAT/CALMS) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Early Language Milestone |

0- 3 yr |

Language |

15 |

Sensitivity

=

0.97

|

|

Scale (ELM)

|

|

|

|

|

Specificity

=

0.93

|

|

Vineland Social Maturity

|

0-15 yr |

Self help, Locomotion, |

25 |

VC = 0.40-0.50 |

|

scale'" |

|

Occupation, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Communication, Self |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Direction,' Socialization |

|

|

|

|

Tests for Indian Children |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Trivandrum Development |

0- 2 yr |

Gross Motor, Fine |

5 |

Sensitivity

=

0.67

|

|

Screeening Chart (TDSC) |

|

Motor, Cognitive |

|

|

Specificity

=

0.79

|

|

Haroda Development |

0- 2V2 yr Gross Motor, Fine |

10 |

Sensitivity

=

0.66 to 0.93

|

|

Screening Test for Infants.

|

|

Motor, Cognitive |

|

|

Specificity

=

0.77 to 0.94

|

* Indian adaptation available.

VC

=

Validity coefficients (Correlations between screening test and other measures of intelligence, language

or adaptive functions).

NA= Not Available.

By far the most commonly used screening test is the Denver Development Screening Test (DDST)(21). The DDST is used to screen children from two weeks through 6 years of age in four developmental domains; gross motor, fine motor adaptive, personal social and language skills. The test consists of ] 05 items but only those items are administered

which are appropriate to the child's age. Each item is scored pass or

fail. A delay score is given to an item which is failed by the child

that is passed by more than 90% of children in the normative age

group. Scores are interpreted as "abnormal", "questionable", or "normal" in each sector. The main usefulness of the test is that it is easy to administer and score and does not require extensive training or experience in testing.

The DDST is most useful in identifying children with moderate to severe motor or cognitive deficit. However its usefulness is limited in detecting more subtle delays(27). The DDST has been shown to have a high specificity and a low sensitivity(28-30). In other words, the test over refers few children but it fails to identify a large proportion of children who are developmentally at risk. Since the "costs" of under identification exceed the costs of over-identification the DDST should be used with care.

The inadequate psychometric properties of the DDST have been attributed to several factors including the scoring system which emphasizes number of failures per developmental sector rather than total number of failures, dearth of items sampling expressive language production, lack of articulation assessment and conclusion of very few items which tap higher congnitive skills(27).

It is important to recognize, however, that all screening tests, and not just the DDST, suffer from various problems of reliability, validity, and poor prediction of later intelligence

(6). Concern has been expressed whether an ideal screening test can

ever be devised given the inherent problems of predicting later intelligence from infant assess- ments(6,31).

Concerns about the inadequate psycho- metric properties of the DDST prompted a major revision of the test and led to the development

of Denver 11(22). The major differences between the DDST and Denver II are an increase in the language items, inclusion of articulation items, a new age scale, a new category of identifying milder delays, and a behavior rating scale(32). However, this test too has been criticized for its limited specificity and has not been extensively used in the Indian setting.

(DPII) (23). The DP II is designed to assess a child's development from birth through age 9Y2. It is an 186 items inventory which assesses a child's functional developmental age in five domains, i.e., physical, self-help, social, academic and communication. The items can be administered via parental inter- view or by direct testing. The DP II is useful for pediatric practice and the Academic subtest samples the better indicators of development, i.e., cognitive, language and fine motor skills. In our own experience with this instrument we find that at younger ages, i.e., less than 2 years, it is not very useful.

Other useful screening tests developed for use by the pediatricians to

assess the development in infants and toddlers with cognitive ages from 1 to 36 months are the Clinical Adaptive Test (CAT) and the Clinical Linguistic Auditory Milestone Scale (CLAMS)(33). The two scales yield

quantitative development quotients for non language visual motor (CAT DQ) and language

(CLAMS DQ) abilities, as well as a composite score of cognitive function. An advantage of this instrument is that the scores help in discriminating children with mental retardation (i.e., both language and visual motor delay) and those with communication disorders (discrepancy between separate scores with language DQ below visual motor DQ).

Although the Indian adaption of the scales is not available, we have found them highly useful instruments and can be reliably used for screening of Indian children.

Since language development is predictive of later intelligence, many clinicians prefer the use of a language-screening test for early detection of developmental delay. The Early Language Milestone Scale (ELM scale) is a screening test of speech and language development for use with children from birth to 36 months(25). The ELM scale consists of 41 items and covers 3 areas of language function: auditory receptive, auditory expressive and visual language. Majority of the items are scored on the basis of parental report. The

scale can be scored in two different ways. The pass/fail scoring techinque is ideally suited for rapid screening of large number of low risk subjects. The point scoring technique can be converted into a quantitative score and the child's language level can be expressed as a percentile score(34). This scoring system is particularly useful in high risk settings such as Neurodevelopmental clinics, Audiology clinics, and Neonatal high risk follow up clinics.

There are several developmental screening tests which have been developed in India (I 7, 18,35-37). For example, the

Trivandrum Development Screening Chart (TDSE) and the Baroda Development Screening Test for Infants

(BDSTI) have been designed for use by the community workers. These tests are

simple and can be administered with minimal amount of equipment and training.

Common Pitfalls of Developmental Screening

When considering the range of develop- mental problems in children, there are several common pitfalls into which an untrained practitioner is likely to fall. Before using any screening instrument in routine practice, clinicians must be aware of both the strengths and weaknesses of screening.

The most common pitfall revolves around the notion that children who are mentally retarded also look different(38). Evidence indicates that the good looking delayed child is typically identified late(39). Conversely, the child with dysmorphic features may not be necessarily intellectually deficient( 40).

Another pitfall of developmental diagnosis which practitioners often fall prey to is when a child with normal or near normal gross motor development is presumed to be of

normal intelligence. Several authors have emphasized that motor milestones are not predictive of intelligence( 41-43) and studies reveal that many children with moderate and severe mental retardation do not demonstrate gross motor delay(44).

In addition, there is a tendency among practitioners to ignore language delay until about 2 years. It is important to remember that language development, which is measured in terms of expressive and receptive capability, is one of the best predictors of later

intelligence, and no parent with a child with language delay should be reassured without appropriate developmental testing.

One of the most serious pitfalls is when the results of development screening tests are used for predicting later developmental status or intelligence of the child(45). In the first two years of life, scores on development tests have limited predictive value for future

development unless the scores are in the very retarded range(46). Predictions improve as the child grows older but are still subject to

serious error because a child may undergo at least two types of changes in

development after the administration of an early screening test(45,

47). One change in the developmental status of the child as he grows

older is due to the acquisition of new skills which are qualitatively

different from earlier skills. For example, it is possible that a

child's development proceeds normally in the first two years and then

starts to lag behind at a later age when new skills such as problem

solving, abstract thinking are tested. Developmental testing at

different ages means different skills are the focus of testing. While

in infancy, developmental testing is confined to testing of sensorimotor

skills, at older ages screening necessarily involves testing of higher mental abilities(3 I). The second problem relates to the change in the child's circumstances, both physically as

well as psychosocial, over a period of time thus altering a child's rate of development. For example, medical problems such as

rickets, severe malnutritions, chronic systemic disease, etc., developed after initial screening may significantly alter child's earlier

developmental status. Environmental factors and psychosocial stressors such as death of a parent, may also delay development. Keeping this in view, it is recommended that no screening test result should be used in

isolation to make a definite statement of diagnosis. Moreover, a child who fails on a screening test should be periodically screened before making a definitive diagnosis.

Most screening tests do not require long training time to reach proficiency, however, failure to follow prescribed procedures in administration scoring and interpretation often lead to invalid results. In order to ensure accuracy it is recommended that only trained persons administer a screening test(45).

Conclusions

The entire process of developmental screening rests on. the premise that early identification of children with

developmental delay can help in starting early treatment and intervention, before it effects the functioning of the child and the family. In order to sucessfully identify children, who require interventions, it is important that the

practitioners be skilled in the use of some screening tests. Although, there is no perfect screening test available, combination of relying on clinical judgement

based on history, physical examination and office observation, addressing parental concerns and performing a formal screening test will help in identifying most children with delayed development.

|

1.

Meisels SJ, Provence S. Screening and Assessment: Guidelines for Identifying Young Disabled and Developmentally Vulnerable Children

and their Families. Washington DC, National Centre for

Clinical Infant Programs, 1989.

2.

Dworkin PH. Developmental screening-expecting the impossible? Pediatrics 1989; 83: 619-621.

3. Singhi P. Ear]y identification of neuro developmental disorders. Indian J Pediatr 1992; 59: 61- 71.

4.

Chaudhari S. Developmental assessment tests: Scope and limitations. Indian Pediatr 1996; 33: 541-545.

5.Committee on Children with Disabilities. Screening infants and young children

for developmental disabilities. Pediatrics 1994; 93: 863-865.

6.

Dworkin PH. British and American recommendations of developmental monitoring: The role of surveillance. Pediatrics 1989; 84: 1000-10 10.

7.

Frankenburg WK. Preventing developmental delays: Is developmental screening sufficient? Pediatrics 1994; 93: 586-593.

8. Blackman, JA. Developmental screening: Infants, toddlers and preschoolers. In: Developmental Behavioral Pediatrics, Eds. Levine MD, Carey WB, Crocker AC. Philadelphia, W.B. Saunders Co., 1'9'92.

9.

Korsch B, Cobb K, Ashe B. Pediatricians' appraisal of patients' intelligence. Pediatrics 1961;27: 990-995.

10.

Bierman JM, Conner A, Vaage M, Honzik MP. Pediatricians' assessment of the

intelligence of two-year olds and their mental test scores. Pediatrics 1964; 33: 680-690.

11.

Dearlove J, Kearney D. How good is general practice developmental screening? Br Med J 1990; 300: 1177-1180.

12. Bowie D, Parry JA. Court come true - for better or for worse. Br Med J 1984; 299: 1322- 1324.

13.

Mc Cune YO, Richardson MM, Powell JA. Psychosocial health issues in the pediatric practice: Parents' knowledge and concerns. Pediatrics 1984; 74: 183-190.

14.

Hart H, Bax M, Jenkins S. The value of a developmental history. Dev Med Child Neurol 1978; 20: 133-181.

15.

Sonnander K. Parental developmental assessment of 18-month-old children: Reliability and predictive value. Dev Med Child Neurol 1987; 29: 351-362.

16.

Glascoe FP, Dworkin PH. The role of parents in the detection of developmental and

behavioral problems. Pediatrics 1995; 95: 829-836.

17.

Phatak AT, Khurana B. Baroda Developmen- tal Screening Test for infants. Indian Pediatr 1991; 28: 29-35.

18.

Nair MKC, George B, Philip E. Trivandrum Development Screening Chart. Indian Pediatr 1991; 28: 869-872.

19.

Lindstrom K, Bremberg S. The contribution of developmental surveillance to early

detection of cerebal palsy. Acta Pediatr 1997; 86: 736-739.

20.

Prechtl HFR. State of the art of a new functional assessment of the young nervous system: An early predictor of cerebral palsy. Early Hum Dev 1997; 50:

1-11.

21.

Frankenburg WK, Dodds J, Fandal A. Denver Developmental Screening Test. Denver

Uni- versity of Colorado Medical Center, 1975.

22.

Frankenburg WK, Dodds J, Archer P, Shapiro H, Bresnick B. Denver-II Screening Manual. Denver, Denver Developmental Materials Inc., 1990.

23.

Alpern G, Boll T, Shearer M. Developmental Profile II (DP II). Los Angeles, Western

Psychological Services, 1986.

24.

Capute AJ, Pamer FB, Shapiro BK, Wachtel RC, Schmidt S, Ross A. Clinical linguistic and auditory milestone scale: Prediction of

cognition in infancy. Dev Med Child Neuro11986; 28: 762-771.

25.

Coplan J. The Early Language Milestone Scale. Austin, PRO-ED, 1987.

26.

Malin AJ. Indian adaptation of Vineland Social Maturity Scale. Lucknow, Indian Psychological Corporation, 1971.

27.

Meisels SJ. Can developmental screening tests identify children who are developmentally at risk? Pediatrics 1989; 83: 578-585.

28.

Camp B, Van Doornick W, Frankenberg W. Preschool developmental screening: A four-year follow up of the Revised Denver Developmental Screening Test and the role of parent report. Clin Pediatr 1977; 16: 257-263.

29.

Borowitz KC, Glascoe FP. Sensitivity of the Denver Developmental Screening Test in speech and language screening. Pediatrics 1986;78: 1075-1078.

30.

Diamond KE. Predicting school problems from preschool developmental screening: A four-year follow up of the Revised Denver Developmental Screening Test and the role of parent report. J Div Early Child 1987; 11: 247-253.

31.

Sattler JM. Assessment of Children's Intelligence and Special Abilities. Boston, Allyn and Bacon Inc., 1982.

32.

Frankenburg WK, Dodds J, Archer P, Shapiro H, Bresnick B. The Denver II: A major

revision and restandardization of the Denver Developmental Screening Test. Pediatrics 1992; 89: 91-97.

33.

Capute AJ, Shapiro BK, Wachtel RC, Gunther UA, Palmer FB. The Clinical Linguistic and Auditory Milestone Scale (CLAMS). Am J Dis Child 1986; 140: 694-698.

34.

Coplan J, Gleason JR. Quantifying language development from birth to 3 years using the early language milestone scale. Pediatrics 1990; 86: 963-971.

35.

Murlidharan R, Bevli U. Developmental norms of Indian Children 2V2 to 5

years-Language and personal social development. Mimeographed. New Delhi, National Council for Educational Research and Training, 1983.

36.

Murlidharan R. Motor development of Indian Children Developmental norms for Indian Children 2V2 to 5 years. Mimeographed. New Delhi, National Council for Educational Re- search and Training, 1983.

37.

Vazir S, Naidu AN, Vidyasagar P, Lansdown RG, Reddy V. Screening test battery

for assessment of psychosocial development. Indian

Pediatr 1994; 31: 1465-1475.

38. Illingworth RS. Pitfalls.in developmental diagnosis. Arch Dis Child 1987; 42: 860-865.

39.

Lock TM, Shapiro BK, Ross A. Age of presentation in developmental disability. J Dev Behav Pediatr 1986; 7: 340-345.

40. Blasco P A. Pitfalls in developmental diagnosis. Pediatr Clin North Am 1991; 38: 1425-1438.

41.

Hreidarsson SJ, Shapiro BK, Capute AJ. Age

of walking in the cognitively impaired. Clin

Pediatr 1983; 22: 248-252.

42.

Neligan G, Prudham D. Potential value off our

early developmental milestones in screening children for increased risk of later

retardation.

Dev Med Child Neurol 1969; 11: 423-428.

43.

Shapiro BK, Accardo PJ, Capute AJ. Factors

affecting walking in a profoundly retarded

population. Dev Med Child Neuro11979; 21:

369-374.

44.

Knoblach H, Stevens F, Malone AE. Manual.

of Developmental Diagnosis. Hagerstown,

Haper Inc., 1980.

45.

Frankenburg WK, Chen JC, Thornton SM.

Common pitfalls in the evaluation of developmental screening tests. J Pediatr 1988; 113:1110-1113.

46. Illingworth RS. The

Development of the Infant and Young Child, Normal, and Abnormal. Baltimore Williams and Wilkins, 1972.

47.

Hall DMB. Developmental tests and scales. Arch Dis Child 1986:213-215.

|