|

Warren Rodrigues

Archana Kher

Surbhi Rathi

Keya Lahiri

Harsh Merchant

From the Departments of Pediatrics and Radiology, B.Y.L. Nair Charitable Hospital, Mumbai. 400 008, India.

Reprint requests: Dr. Keya Lahiri, B/10, Vijay Kunj, J.N. Road, Santacruz (East),

Mumbai 400 055, India.

Manuscript Received: May 5, 1998; Initial review completed: June 13, 1998;

Revision Accepted: July 30, 1998.

Recurrent seizures have causes that are protean and pose

a diagnostic and management challenge. Neuroimaging, mainly Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) gives a better insight into the etiology and a clinicopathological correlation of the disorder(1). More number of cases of neuronal migration disorder and cortical dysplasia can now be diagnosed. We report a case of cortical dysplasia which was described as pachygyria, giving rise to recurrent seizures.

Case Report

We were presented with a 9-year-old, right handed male child with

complaints of recurrent convulsions. Being asymptomatic until two years

of age with no significant birth history, the child developed focal convulsions becoming

generalized. They were essentially involving the left half of the body,

beginning with the fingers, ascending to involve the left arm, the face, with deviation of the eyes to the left along with frothing at mouth. Each episode lasting

for 3 mintues was preceded by an aura and succeeded by post-ictal weakness involving the left half of the body with deviation of the angle of mouth to the same side. The deficit appeared within an hour of the seizure gradually and recovered over a period of 10 days.

The child received an array of anti-convulsants in the form of phenobarbitone, phenytoin, sodium valproate and carba-mazepine

in various combinations for a period of 7 years but had poor seizure control. There was no history of head trauma or seizure disorder in the family.

Examination revealed a head circumference of 50 cm which was at the 2SD deviation for his age. The patient had normal vital parameters, no neuro-cutaneous markers or stigmata of tuberculosis. The

child was conscious, co-operative, oriented with no meningeal signs, dysarthria, apraxia or agnosia.

A left upper motor neuron facial palsy was noted on CNS examination. The deep tendon reflexes were exaggerated on the left with Babinski

sign positive on the same side. Modalities of touch, pain, temperature

and the vibration sense were maximally reduced on the left, left astereognosis being conspicuous. There was no incoordination or involuntary movements and a minimal circumduction gait was observed on walking. The motor deficit gradually improved over the next 10 days.

With history of recurrent seizures, left astereogonosis and a hemiplegia-'not dense' but recovering, a lesion localized to the right cerebral cortex was contemplated. Causes of recurrent strokes such as Moya- Moya disease, sickle-cell anemia, MELAS, homocystinuria, embolic episodes and hyperlipidemia were considered. However, the cause of the left sided transient weak- ness could be attributed to none other than Todd's paralysis.

The child was investigated keeping in view the above etiologies and the same are summarized below. Hemogram, renal pro- file, liver profile including serum ammonia, lipid profile and serum lactate were within normal range. A urinary amino-acidogram, performed for homocystinuria was normal. A fundoscopy confirmed the absence of papilloedema but the presence of a chorio-retinitis scar in the left fundus

was detected. Right mild conductive deafness and left profound mixed hearing loss were noted on audiogram. EEG was suggestive of a right epileptiform focus. IQ on Kamath's scale was 60. Titres for intra- uterine infections were not very helpful and revealed low positive IgG for toxo-plasma and cytomegalovirus. However,

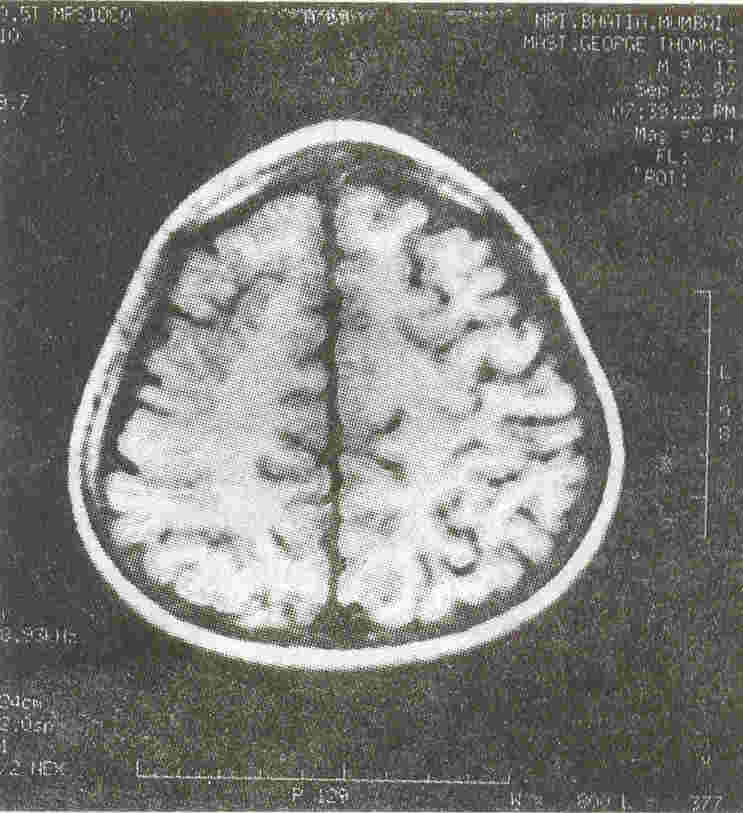

IgM for both infections was negative. Among the neuro-imaging modalities, the CT scan (brain), plain and contrast did not reveal any abnormality. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (Brain) was essentially diag- nostic. MRI revealed a thickening of the cortical grey matter in the right fronto- parietal lobes. There was a paucity of sulcal spaces herein and few of them were found to be shallow (Fig. 1). These findings were in keeping with the diagnosis of pachygyria which is a form of cortical dysplasia.

Discussion

The word 'dysplasia' refers to an abnormality of development and in pathology means an alteration in size, shape and organization of cells. When dysplasia involves the cerebral cortex the latter may act as an irritant focus leading to recurrent seizures. A synopsis of cellular maturation and migration of the brain during embryonic and fetal life would aid understanding the concept of cerebral cortical dysplasias.

|

|

Fig. 1. MRI brain (Tl weighted) image showing broad flat

sulci. |

During the seventh gestational week, neuronal and glial precursors are generated

in the germinal plate that lines the lateral and the third ventricles. Migration of young neurons occurs along the radial glial fibres that extend from the ventricle outwards to form the cortical plate.

Early

arriving neurons take deep positions in the cortex and later arriving neurons, superficial positions, i.e., "inside out" rule(2). A

direct correspondence exists between the site of cell proliferation within the germinal zone and the location with the cerebral cortex. Any alteration in the above gives rise to a neuronal migration defect/ disorder, as discussed.

Cerebral cortical dysplasias can be broadly categorized into two main types namely lissencepalic and non-lissencephalic(3). The non-lissencephalic cortical dysplasias are more of histologic

descriptions and are not easily discerned on MRI scans. They could be diffuse or focal or unilateral or bilateral. Poly-microgyria and Pachygyria are two structural variants of the non-lissencephalic type. The former refers to a diffusely thickened abnormal cortex that has an irregular "bumpy gyral

pattern" with relative paucity of under- lying white matter, whereas the latter

includes focal areas of thickened and flattened cortex giving rise to widened gyri with decreased number of sulci. Associated with pachygyria is the cerebrohepatorenal syndrome of Zellwegar.

However, our patient did not show any resemblence to this syndrome and only had

the typical appearance on MRI. Lissencephalic or agyric or

smooth brain is characterized by a shallow Sylvian fissure and almost no surface sulcation. The insult giving rise to lissencephaly occurs between the third and fourth month of gestation. Lissencephaly

has three types. Type I is a brain characterized by colpocephaly or thickened cortex,

the gyri are typically flat and broad and the shallow Sylvian fissure gives the brain a figure of '8' appearance. Type II or agyria is a brain with poorcortico-medullary demarcation, a thickened cortex with hypo-myelination of white matter. Enlarged ventricles, hypoplastic cerebellum and brain

stem are essential features of Type III. Miller-Dieker syndrome and Walker- Warburg syndrome are associated with Type I and II lissencephaly, respectively.

Other disorders of neuronal migration include Heterotopias and Schizencephaly. Heterotopias are gray matter collections of otherwise normal neurons in abnormal locations which occur secondary to arrest of neuronal migration along the radial glial fibres. Laminar and Nodular are two of its types. Schizencephaly means split-brain is characterized by a gray matter lined CSF filled cleft extending from ependymal surface through the white matter to the pia. There are two types, closed and open lip.

Vascular insult during the third or fourth month of gestation has been postulated as one etiology. Intrauterine infections with cytomegalovirus and, Toxoplasma gondii have been incriminated. Most cases are sporadic but autosomal recessive cases are also known. Dysplasias like these are known with 'Fetal Alcohol Syndrome', wherein the neurons behave like 'drunk neurons' and follow a bizzare pattern of migration(4).

Clinical presentations essentially include microcephaly, disorders of tone, paucity of movements, feeding disturbances and refractory seizures. All cases have severe EEG abnormalities in the form of high amplitude and rapid frequency. Intellect is often impaired.

Our case had microcephaly, intellectual impairment, seizures, impaired cortical sensations and motor deficits. A chorioretinitis scar in the left fundus

coupled with

hearing impairment led us to postulate the probable etiology as cytomegalovirus in this case. In conclusion, Magnetic Resonance Imaging has an important role to play in the diagnosis of these conditions.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank the Dean, Dr. K.D. Nihalani for permitting them to publish this interesting case. We also thank Dr. A.B. Shah, Honorary Professor of Neurology who helped us in evaluating the case.

|

1.

Ashwal S. Congenital structural defects. In: Pediatric Neurology-Principles and Practices, Volume 1, 2nd edn. Ed.

Swaiman K F. Chicago, Mosby Year Book Inc 1994; pp 421-470.

2.

Volpe

J J.

Neuronal proliferation, migration, organisation and myelination. In: Neurology of the Newborn, 3rd edn. Philadelphia, W.B. Saunders Company, 1995; pp 43-92.

3.

Osborn AG, Boyer RS. Disorders of diverticulation, sulcation and cellular migration. In: Brain Development and Con- genital Malformations-Part I: Dignostic Neuroradiology. Chicago CV Mosby Year Book Inc, 1994; pp 37-58.

4.

Campbell AGM, 'Me Intosh N, Brown JK. Disorders of the CNS. In: Forfar and Arneil's Text Book of Pediatrics, 4th edn. Edinburg, ELBS with Churchill Livingstone 1994; pp 713-918.

|