|

|

|

Indian Pediatr Suppl 2009;46: S37-S42 |

|

Pyritinol for Post-asphyxial Encephalopathy in

Term Babies – A Randomized Double-Blind Controlled Trial |

|

MKC Nair, Babu George and L Jeyaseelan*

From Child Development Centre, Medical College,

Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, India and

*Department of Biostatistics, Christian Medical College, Vellore,

Tamilnadu, India.

Correspondence to: Dr MKC Nair, Professor of Pediatrics

and Clinical Epidemiology and,

Director, Child Development Centre, Medical College, Thiruvananthapuram

695 011, Kerala, India.

E-mail: [email protected]

|

Abstract

Objective: To evaluate the efficacy of

pyritinol in improving the neurodevelopmental outcome at one year of age

among term babies with post-asphyxial encephalopathy.

Setting: Level II Neonatal Nursery and Child

Development Centre, Medical College, Thiruvananthapuram.

Design: Randomised placebo controlled double

blind trial.

Participants: 108 term babies with post-asphyxial

encephalopathy, stratified into three grades based on clinical criteria.

Intervention: The treatment group (n=54) received

pyritinol and the control group (n=54) received placebo, in exactly the

same increasing dosage schedule of 1 to 5mL liquid drug (20-100 mg) from

8th postnatal day until the end of six months.

Outcome variables: Mean Mental Development Index

(MDI) and mean Psychomotor Development Index (PDI) measured on Bayley

Scales of Infant Development at one year of age.

Results: No statistically significant difference

was observed in MDI or PDI scores at one year between the treatment and

control groups. The confidence interval for the differences ranged from

–6.3 to+8.7 for MDI and from –4.1 to+12.7 for PDI. On multiple

regression analysis using one year MDI and PDI scores, even after

controlling for birthweight, there was no statistically significant

difference between the treatment and control groups.

Conclusion: Pyritinol is not useful in improving

the neurodevelopmental status of babies with post-asphyxial

encephalopathy at one year of age.

Keywords: Neurodevelopmental outcome, Post- asphyxial

encephalopathy, Pyritinol.

|

|

P

erinatal hypoxia has been

recognized as a possible cause of mental and physical handicaps in

childhood for more than 100 years(1). Approximately 23% of the 4 million

annual global neonatal deaths are attributable to birth asphyxia(2). In a

prospective cohort study undertaken in the principal maternity hospital of

Kathmandu, an upper estimate for the prevalence of major neuro-impairment

at 1 year, attributable to birth asphyxia was 1 per 1000 live births(3).

The best predictive risk factors for the neurological prognosis at

follow-up is reported to be severe perinatal asphyxia at birth and/or

evidence of encephalopathy in neonatal period(4,5). Newborn encephalopathy

(Grades I, II and III), particularly with seizures and recurrent apnea,

has been demonstrated to be an important predictor of subsequent motor and

cognitive handicaps(6-9). Clinical presentation of birth asphyxia with

severe newborn depression has demonstrated that most children who survived

with sequelae had clinical signs of encephalopathy during the neonatal

period(10).

Pyritinol or pyritinol dihydrochloride mono-hydrate, is

a derivative of pyridoxine with a chemical structure of two pyridoxine

molecules linked by a disulphide bridge and has only 0.1% of vitamin B6

activities. Benesova, et al.(11), based on a controlled trial of

pyritinol, reported significant improvement in neurodevelopmental outcome

at one year and every year after that till six years of age. However, this

was not a controlled trial and hence the results, not conclusive. The drug

was effective only if used early and for prolonged periods(12). This drug

is not routinely used in our hospital nursery and during follow up,

although pediatricians may use it in individual cases. Only a randomized

controlled double blind trial can give a definite answer on the efficacy

of pyritinol in perinatal asphyxia.

The broad objective of the study was to evaluate the

efficacy of pyritinol in improving the neurodevelopmental outcome at one

year of age among term babies with post-asphyxial encephalopathy, using

Bayley Scales of Infant Development (BSID), the most widely accepted

objective developmental assessment tool(13). The hypothesis tested in this

randomized placebo controlled double blind trial was that the mean Mental

Developmental Index (MDI) and the mean Psychomotor Developmental Index

(PDI) scores obtained in BSID, for the group of term post-asphyxial

encephalopathy babies receiving pyritinol is greater than for the control

group of babies.

Methods

A sample size of 54 in each group was calculated to

detect a mean clinically significant difference of 16 in the MDI or PDI

scores for two-tailed test with 90% power, significance level at 0.05 and

with 5% drop-out rate(14). A pilot study was done on a sample of 15 babies

with post-asphyxial encephalopathy.

The sequential criteria for inclusion in the study

were: born in the labor room of Medical College, Thiruvananthapuram;

completed 37 weeks of gestation; admitted to the special care nursery with

a clinical diagnosis of birth asphyxia; clinical evidence of

encephalopathy observed in the first 7 days of postnatal life; alive on

8th postnatal day; and, parents agreeing to randomization and monthly

follow-up. The specific exclusion criteria were, total serum bilirubin

more than 15mg/dL on the 7th postnatal day, blood glucose level less than

30mg/dL recorded on two occasions 4 hours apart any time during the first

7 days of postnatal life, neonatal meningitis in the first 7 days of life,

chromosomal anomaly, microcephaly, hydrocephalus, and any congenital

anomaly known to affect growth and development.

The study was conducted with the approval of the

ethical committee of the Medical College, Thiruvananthapuram. After

obtaining the informed consent, participants were randomized on the 8th

post natal day into treatment and control groups, using block

randomization and separate random number series for the three grades to

get the same number of treatment and control patients in each grade (I, II

and III) of post-asphyxial encephalopathy. Serially numbered opaque

envelops, containing the allocation detail of a subject were developed at

the Department of Biostatistics, Christian Medical College, Vellore.

Both the groups of babies received similar treatment as

per the routine practice of the hospital till the 8 th

postnatal day. Eligible cases received, according to the randomized

coding, placebo or active drug (pysitimol, 1 mL=20 mg) both having same

consistency, colour and smell and the only difference being the batch

number. The same dosage schedule was followed for drug and placebo and

given orally as a single dose in the morning so as to avoid any possible

sleep disturbances. A calibrated 1 ml medicine dropper was supplied for

ease of administration of correct dose at home.

The increasing dosage schedule included 1 mL of the

solution (placebo/pyritinol) per day from day 8 to day 30, increased by 1

mL every 15 days to 5 mL per day by day 76. This amount of the solution

was continued till six months of age.

The parents were given a detailed discharge summary and

a special Child Development Centre monthly follow-up schedule card.

Contamination was avoided by checking the details of any medication

received for more than one week. The medication bottle was brought along,

collected and measured as an indicator of compliance. During the monthly

follow-up visit, the mother was asked about any problem the baby had in

the previous month and a thorough physical examination was done,

specifically looking for any possible side effect of the drug. Any rash

resembling a drug rash, clinical jaundice after one month of age, clinical

increase in liver size at least 2cms more than on the previous visit and

proteinuria (qualitatively reported as 2+ or above) were specifically

noted.

The one year primary outcome measurement was Mental

Development Index and Psychomotor Development Index obtained on the Bayley

Scales of Infant Development (BSID), Baroda, India norms. BSID was

administered in a separate quiet room by a well-trained observer blind to

the treatment status of the babies. Every effort was made to adhere to the

detailed instructions of the BSID test manual(13). The test items were

presented in order of difficulty and those items passed were ticked, but

added up only at a later stage to avoid any test bias. The raw scores

obtained separately for mental scale and motor scale, by adding together

the number of items passed on each scale separately, were then converted

to MDI and PDI scores, respectively, using conversion tables provided in

the test manual. Secondary outcome measurements at one year included

weight taken without clothes, using a beam type of weighing machine

calibrated against a standard weight once-a-week, length taken using a

simple infantometer, (with the baby supine, knees together and legs in a

straight position) and, head circumference measured using a metal tape

running through the most prominent part posteriorly and just above

glabella anteriorly.

The criteria for loss to follow-up was not reporting

for 1 year assessment of outcome variables even after sending two

reminders to the home address and one to the alternative address at 7 days

interval and evidence of having left the place. Quality check of the data

being collected was done by perusal of individual data sheets at the

weekly meetings of the research team. Out of 108 babies randomised on the

8 th postnatal day, 100 babies

(treatment group 51, control group 49) with outcome measurements available

at one year, were included in the initial "intention to treat" analysis.

All 100 babies had received the trial medication for periods of 75% or

more of the total days the baby should have received the medication.

Therefore, there was no need to consider any separate analysis of those

with completed treatment. An analysis of the baseline characteristics was

done using chi-square statistic and student’s t-test to look for

any statistically significant differences between the treatment and

control groups. To test the hypothesis regarding MDI and PDI, Student’s

t-test was used to compare means of the two independent samples, after

seeing that the data were approximately normally distributed. A 95%

confidence interval for the true difference in population means was also

calculated. Multiple regression analysis using MDI and PDI scores at one

year of age was done with pyritinol/placebo and any baseline variable with

significant difference between the groups, as explanatory variables.

The double blind nature of the study was strictly

maintained at all stages of the trial. An independent person kept the

coding about the treatment status of the patient. The parents of the

babies, the neonatal consultant, the investigator, the research assistants

and the outcome evaluators did not know the treatment status of the

babies.

Results

During the recruitment period of 17 months there were a

total of 21,604 deliveries, with 349 babies with diagnosis of asphyxia. Of

these, 155 did not develop post-asphyxial encephalopathy, 20 babies

meeting exclusion criteria were excluded and 62 babies died in the labor

room or nursery, leaving 112 cases of post-asphyxial encephalopathy

available for randomi-sation on the 8th postnatal day. Excluding four

babies whose parents expressed inability to come for monthly visits, 108

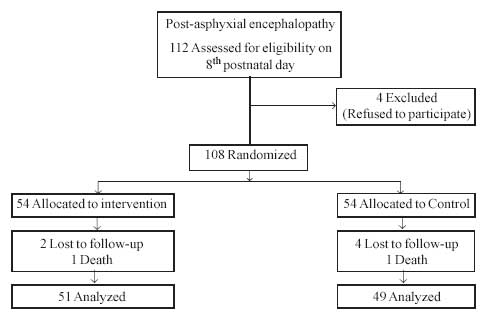

babies were randomised (Fig. 1). After block randomisation

we could obtain only 5 each of grade II and 2 each of grade III

encephalopathy, possibly because it is babies with severe asphyxia who are

likely to develop grade II and III encephalopathy, who die early and

cannot be saved without ventilator support.

|

|

Fig. 1 Flow diagram of patients in the

study. |

Table I shows comparison of baseline

characteristics of the two groups at the time of randomization. There was

a statistically significant difference observed for the weight at birth

between treatment and control groups. Table II shows no

statistically significant difference in MDI or PDI scores at one year

between the treatment and control groups. There were also no statistically

significant differences observed between the treatment and the control

groups on growth parameters of weight, height and head circumference. As a

statistically significant difference was observed for the weight at birth

between treatment and control groups, adjustment for this potential

confounder was needed in the analysis of outcomes. On multiple regression

analysis using one year MDI and PDI scores, even after controlling for

birth weight there was no statistically significant difference between the

treatment and control groups.

TABLE I

Comparison of Treatment and Control Groups at Randomization

| Characteristics |

Treatment (n=54) (SD) |

Control (n=54) (SD) |

P value |

| Encephalopathy |

|

|

1.0 |

| Grade I |

47 |

47 |

|

| Grade II |

5 |

5 |

|

| Grade III |

2 |

2 |

|

| Abnormal delivery |

27 |

27 |

1.0 |

| Male: female ratio |

32:22 |

34:20 |

0.34 |

| Low birthweight (<2500g) |

11 |

15 |

0.49 |

| Low SE status |

40 |

43 |

0.64 |

| Mean weight at birth |

2841 (513.1) |

2627 (461.3) |

0.02 |

| Mean length at birth |

48.1 (2.8) |

48.0 (1.8) |

0.76 |

| Mean head circumference at birth |

33.7 (1.9) |

33.2 (1.1) |

0.10 |

| Mean gestational age |

39.1 (1.3) |

39.1 (1.3) |

0.95 |

| Days of nursery stay (mean) |

3.7 (2.1) |

4.0 (3.6) |

0.70 |

| Mother’s education (years) (mean) |

7.5 (3.2) |

8.2 (2.9) |

0.31 |

| Father’s education

(years) (mean) |

7.4

(2.6) |

8.1

(2.6) |

0.18 |

TABLE II

Comparison of Mental Development Index Score, Psychomotor Development Index

Score and Growth Parameters at 1 Year

| Score |

Treatment Group

(n=51)

Mean (SE) |

Control Group

(n=49)

Mean (SE) |

Difference in Means

(95% CI)

|

P value |

| Mental Development Index |

91.6 (2.9) |

92.8 ( 2.5) |

1.2 (–6.3, +8.7) |

0.75 |

| Psychomotor Development Index |

96.0 (3.2) |

100.3 (2.7) |

4.3 (–4.1, +12.7) |

0.31 |

| Weight (kg) |

8.6 (0.2) |

8.6 (0.2) |

0.0 (–0.5, +0.5) |

0.86 |

| Length (cm) |

71.9 (1.4) |

72.1 (1.5) |

0.2 (–3.8, +0.5) |

0.94 |

| Head circumference (cm) |

44.8 (0.2) |

45.0 (0.2) |

0.2 (–0.4, +0.8) |

0.63 |

Discussion

As physicians we always feel inadequate if we cannot

offer drugs for a medical problem that we face and birth asphyxia is no

exception. The drug pyritinol is widely used among asphyxiated babies by

practitioners in India, South East Asia and some East European countries,

even without strong evidence and hence this study is timely and

appropriate. Availability of good objective outcome measurements is

crucial for successful completion of any good trial. The objective

neurodevelopmental measurement of MDI and PDI using Bayley scales of

infant development standardized for the Indian population were used as the

one-year outcomes in this study(14).

One of the main issues that we have to face when we try

to relate asphyxia and outcome is the problem of defining post-asphyxial

brain damage(15). We chose post- asphyxial encephalopathy as marker of

asphyxia in this study because of the dual advantage of fairly accurate

prediction of outcome and generalisability, as majority of neonatal units

in India are level II without ventilation facilities.

This trial has failed to show any evidence to suggest

that pyritinol is useful in improving the neurodevelopmental status at one

year of age. For any negative trial result it is important to consider the

following methodological issues. Firstly, did the study have adequate

power? The sample size calculated to detect a clinically significant

difference of 16 MDI or PDI score with 90% power at 0.05 significance

level was 96 and we have one year out come measurements available for 100

babies. Secondly, did the study get adequate drug compliance? For all the

babies for whom one-year outcome measurements were made, there was

evidence that they had consumed more than 75% of the total expected drug/

placebo. Thirdly, did the study have mortality and or complications? There

were two deaths one on the 58th day, a case of grade-III encephalopathy

belonging to the control group, and the other baby belonging to the

treatment group died at home due to bronchopneumonia, both likely to be

unrelated to use of drug. None of the babies belonging to either the

pyritinol or the control group had evidence of drug complications. This

was the same as observed in the Prague study(11), suggesting that the drug

is safe to be used in infants at doses below 100 mg per day.

Retrospective power calculations were done for MDI and

PDI. The current power is 6% and 19% respectively. At the planning stage,

the study group expected minimum of 16 units difference between the two

arms as this was clinically meaningful difference and we wanted to

achieve. However, the current power suggested that the Pyritinol arm is as

good as control arm. This implied fact that the effect due to Pyritinol is

absolutely nil. It is also evident that failing to reject the null

hypothesis is not due to lesser numbers. Moreover, it is unwise to show a

small difference in MDI to be statistically significant by recruiting

thousands of children.

This study has failed to show any positive effect of

pyritinol in improving the neurodevelopmental status of babies with

post-asphyxial encephalopathy at one year of age. Therefore, widespread

use of the drug should be discouraged not only for economic reasons but

also for ethical reasons.

Acknowledgments

Director and faculty of Centre for Clinical

Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of New Castle, Australia; Staff

of Neonatal Nursery; Asokan N, and other staff of Child Development

Centre, Medical College, Thiruvananthapuram.

Contributors: MKCN was involved in designing the

study and preparation of the manuscript and will act as guarantor. BG was

involved in the data collection and manuscript writing, LJ was involved in

analysis of data.

Funding: M Med Sc Research Grant, University

of New Castle.

Competing interests: None stated. The findings and

conclusions in this study are those of the authors and do not necessarily

represent the views of the funding agency.

|

What the Study Adds?

• Pyritinol does not improve neurodevelopmental

status of babies with post-asphyxial encephalopathy at one year of

age. |

References

1. Little WJ. On the influence of abnormal parturition,

difficult labour, pre-mature birth and asphyxia neonatorum on the mental

and physical condition of the child; especially in relation to

deformities. Transact of the Obst Soc London 1862; 3: 293-344.

2. Lawn JE, Cousens S, Zupan J. 4 million neonatal

deaths: When? where? why? Lancet 2005; 365: 891-900.

3. Ellis M, Manandhar N, Shrestha PS, Shrestha L,

Manandhar DS, Anthony M. Outcome at 1 year of neonatal encephalopathy in

Kathmandu, Nepal. Dev Med Child Neurol 1999; 41: 689-695.

4. Gonzalez de Dios J, Moya M. Perinatal asphyxia,

hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy and neuro-logical sequelae in full-term

newborns. II. Description and interrelation Rev Neurol 1996; 24: 969-976.

5. Gonzalez de Dios J, Moya M, Vioque J. Risk factors

predictive of neurological sequelae in term newborn infants with perinatal

asphyxia. Rev Neurol 2000; 32: 210-216.

6. Sarnat HB, Sarnat MS. Neonatal encephalopathy

following foetal distress. Arch Neurol 1976; 33: 696-705.

7. Fenichel GM. Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy in the

newborn. Arch Neurol 1983; 40: 261-266.

8. Nelson KB, Ellenberg JH. Neonatal signs as

predictors of cerebral palsy. Pediatrics 1979; 64: 225-232.

9. Low JA, Galbraith RS, Muir DW, Killen HL, Pater EA,

Karchmar EJ. The predictive significance of biologic risk factors for

deficits in children of a high-risk population. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1983;

145:1059-1068.

10. Scott H. Outcome of severe birth asphyxia. Arch Dis

Child 1976; 51: 712-716.

11. Benesova O, Petova J, Vinsova N (Eds.). Perinatal

distress and brain development. Prague: Avicenum, Czechoslovak Medical

Press 1980. p. 52-130.

12. Petova J, Vinsova N, Benesova O. Psychomotor

development of high risk neonates during early and long-term

administration of pyritinol. Cesk Neurol Neurochir 1979; 42: 402-412.

13. Phatak P (Ed). Manual for using Bayley Scales of

Infant Development based on Baroda studies and Baroda norms, India: MS

University of Baroda 1973.

14. Dobson AJ. Calculating sample size. Transactions of

the Menzies Foundation 1984; 7: 75-79.

15. Shankaran S, Woldt E, Koepke T, Bedard MP, Nandayal R. Acute

neonatal morbidity and long-term central nervous system sequelae of

perinatal asphyxia in term infants. Early Hum Dev 1991; 25: 135-148. |

|

|

|

|