|

|

|

Indian Pediatr Suppl 2009;46: S20-S26 |

|

Effect of Child Development Centre Model Early

Stimulation Among At-risk Babies – A Randomized Controlled

Trial |

|

MKC Nair, Elsie Philip, L Jeyaseelan, Babu George, Suja

Mathews and K Padma

From Child Development Centre, Medical College,

Thiruvananthapuram 695 011, Kerala, India.

Correspondence to: Dr MKC Nair, Professor of Pediatrics

and Clinical Epidemiology, and Director,

Child Development Centre, Medical College, Thiruvananthapuram 695 011,

Kerala, India.

E-mail: [email protected]

|

Abstract

Objective: To study the effectiveness of Child

Development Centre (CDC) model early stimulation therapy done in the

first year of postnatal life, in improving the developmental outcome of

at-risk neonates at one and two years of age.

Design: Randomized controlled trial.

Setting and subjects: The study participants

included a consecutive sample of 800 babies discharged alive from the

level II nursery of Medical College, Thiruvananthapuram.

Intervention: The control group received routine

postnatal check-up as per hospital practice. Intervention group in

addition received CDC model early stimulation therapy (home-based).

Results: The intervention group of babies had a

statistically significant higher score for mental developmental index

(MDI) and psychomotor developmental index (PDI) at one and two years of

age. After adjusting all significant risk factors for development, the

babies who had intervention had significantly higher Bayley scores, 5.8

units at one year and 2.8 units at two year, as compared to control

babies.

Conclusion: Early stimulation therapy was

effective at one year. The beneficial effect also persisted at two

years, without any additional interventions in the second year.

Key words: At-risk neonates, Child development, Early

stimulation, Intervention, MDI, PDI.

|

|

T

here is an increasing awareness

among pediatricians on the role of the environment in mental and cognitive

development. Early stimulation programs were developed that targeted

preservation of the mother-infant relationship, improved stimulation for

preterm infants and reduced stress in the neonatal nursery(1). By early

"infant stimulation" we mean early interventional therapy for babies

at-risk for developmental delay. Developmental deficits occur among babies

with genetic and metabolic disorders, environmental risk factors and

biological risk factors like low birth weight(2). Infants born low

birthweight (<1800g) to disadvantaged mothers are at developmental risk

for both biological and social reasons(3).

Meta-analysis of early intervention efficacy studies

has shown that early intervention is effective in improving the

developmental status, although there is no uniform agreement as to whether

the effects last long(4). A recent Cochrane review of sixteen studies has

shown that early intervention programs for preterm infants have a positive

influence on cognitive outcomes in the short to medium-term(5). Long-term

developmental follow-up of at-risk babies in the community, supported by

early intervention therapy needs to be established, as shown by the

experience in the developed countries(6). Large community early

stimulation programs have shown that efficacy was greatest with programs

involving both the parents and the baby; long-term stimulation improved

cognitive outcomes and child-parent interactions, cognition showed greater

improvements than motor skills and, larger benefits were obtained in

families that combined several risk factors(7).

In India, it has been shown that early intervention

program can be successfully conducted through the high risk clinic

approach(8). But, before a national policy is evolved in this regard, a

randomized controlled trial showing efficacy of early inter-vention is

mandatory. Hence this randomized controlled trial was conducted to study

the effective-ness of Child Development Centre (CDC) model early

stimulation therapy, done in the first year of postnatal life, in

improving the developmental outcome among at-risk babies.

Methods

The study was conducted at the level II neonatal

nursery of Sree Avitam Thirunal (SAT) hospital and follow-up was done at

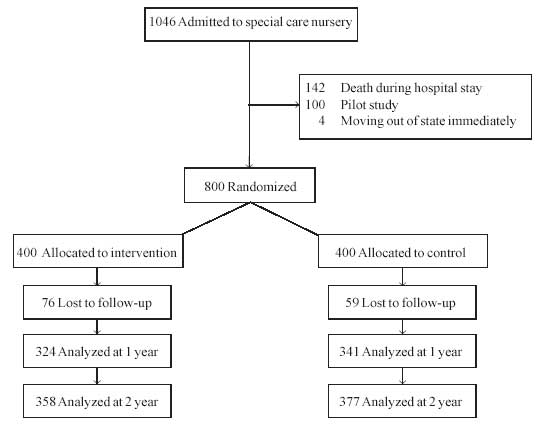

CDC, Medical College, Thiruvananthapuram (Fig. 1). The entry

criteria included; born in SAT hospital, admitted to level II neonatal

nursery, discharged alive and, informed consent for follow-up and early

stimulation. No exclusion criteria were used, so as to give

generalisability to the results obtained. A pilot study on a sample of 100

babies was done to make sure that the randomization procedure, early

stimulation, outcome measure-ments and blinding proceeded as planned.

|

|

Fig. 1 Participant flow in the study. |

Sample Size: As this was designed as a

pragmatic clinical trial, the study participants included a consecutive

sample of 800 babies discharged alive, with no exclusion criteria. A

sample size of 336 in each group was obtained, which was adequate to

detect between groups, 4 clinically significant mental developmental index

(MDI), using Bayley scales of infant development (BSID) with alpha error

of 5% and beta error of 20%. A difference of 4 in the MDI scores was taken

as clinically significant difference because it is same as ¼ standard

deviation on Bayley scales, after normalisation of the raw scores to

scores with a mean of 100 and standard deviation of 16 as explained in the

Bayley manual(9,10). Allowing for 20% loss to follow-up, a total of 800

eligible subjects, who met all the inclusion and exclusion criteria were

randomised to intervention and control group on the day of discharge.

Randomization and allocation: Simple

randomisation was done using RALLOC software. Serially numbered opaque

envelops containing the allocation details of a subject were developed at

the Department of Biostatistics, Christian Medical College, Vellore. The

control group received the routine postnatal check-up as per hospital

practice and the intervention group, in addition, received CDC model early

stimulation therapy(11). CDC model early stimulation aims at stimulating

the child through the normal developmental channel, prevention of

developmental delay, prevention of asymmetries and abnormalities,

detection of transient tone abnormalities and minimization of persistent

tone abnormalities. The four major sensory modalities used are; visual

stimulation, auditory stimulation, tactile stimulation and

vestibular-kinaesthetic stimulation. An occupational therapist at CDC,

trained the mothers individually and in groups, to give CDC model early

stimulation and the mothers continued to do the same at home. The

compliance was assessed during monthly follow-up visits by observing the

ease with which the mother did the early stimulation. Compliance score was

derived from a structured questionnaire designed for this purpose, with a

total score of 35, any score below 31 was taken as poor compliance and

above 31 as good compliance.

Outcome measurements were made at one and two years of

age by an observer blind to the treatment status of the babies. These

included MDI, PDI and Bayley score derived as per the Bayley manual. The

Bayley scores represent the motor and mental raw scores together and, MDI

and PDI represent the deviation quotients for mental and motor scores,

respectively. Anthropometric measurements of weight, length and head

circumference were measured as per standard procedure. Those who did not

report for one-year assessment were contacted individually at home before

the second-year assessment.

Quality check of the data collected was done by perusal

of individual data sheets and random checking of about 10% of the

admission record sheets by the principal investigator. Data were entered

and analysed using Foxplus, and SPSS PC+ softwares. For continuous

outcome, Student’s t-test was used to compare the means in the two

groups. Student’s t-test and two-way analysis of variance were used

to compare the means of the study variables between intervention and

control group. A 95% confidence interval for the true difference in means

was also calculated. For multivariate analysis, the study variables, which

were significant at 10% level of significance in bivariate analyses, were

considered. Stepwise multiple regression analysis was done separately for

MDI, PDI and Bayley scores at the end of first and second year.

Significance of the regression model was obtained by F test. R 2

was also computed. Wald test was used to identify the significance of the

variables included in the model. The ethical committee of Medical College,

Trivandrum provided the ethical clearance for the study.

Results

A total of 1046 babies, born in SAT hospital were

admitted to the level II neonatal nursery during the study period. Out of

these 142 babies died in the nursery, 100 babies were used for the pilot

study and 4 babies planned to move outside the state and hence could not

participate in the study. Outcome measurements were available at the end

of one year for 665 babies excluding 135 lost to follow-up, and at the end

of second year for 735 babies excluding 65 lost to follow-up. Table

I shows that the baseline variables are equally distributed in

both arms. Nearly one third of the mothers studied up to middle school. Of

the children studied, nearly 27% were preterm and 50-55% of the babies

were born with low birth weight. Nearly one fourth of them were SGA.

Table II shows one year and two-year outcomes by intervention

and control groups. There was a statistically significant difference

observed with the intervention group having a higher score for MDI, PDI,

Bayley score and length both at one year and two year.

TABLE I

Study Variables at Baseline

Study variable

|

Intervention

n (%) |

Control

n (%) |

|

Residence: Rural |

298 (74.5) |

324 (81.0) |

|

Religion |

|

|

| Hindu |

304 (76.0) |

278 (69.5) |

| Muslim |

56 (14.0) |

55 (13.8) |

| Christian |

40 (10.0) |

67 (16.8) |

| Male sex |

217 (54.3) |

221 (55.3) |

| Caste |

| SC/ST |

33 (8.4) |

42 (10.6) |

| Others |

360 (91.6) |

356 (89.4) |

| Education of father |

| Middle school |

130 (32.8) |

130 (33.0) |

| High school |

266 (67.2) |

264 (67.0) |

| Education of mother |

| Middle school |

125 (31.6) |

134 (33.9) |

| High school |

271 (68.4) |

261 (66.1) |

| Occupation of father |

| Irregular job |

181 (46.3) |

198 (50.5) |

| Employed |

210 (53.7) |

194 (49.5) |

| Occupation of mother |

| Not employed |

352 (90.7) |

354 (90.8) |

| Employed |

36 (9.3) |

36 (9.2) |

| Families with 1 child |

111 (29.0) |

108 (28.4) |

| Monthly income |

| Low |

266 (68.4) |

272 (69.9) |

| High |

123 (31.6) |

117 (30.1) |

| Nuclear family |

98 (25.6) |

115 (29.8) |

| Joint family |

285 (74.4) |

271 (70.2) |

| Birth order >1 |

174 (44.6) |

161 (41.4) |

| Consanguinity |

39 (9.8) |

37 (9.4) |

| High risk pregnancy |

133 (33.6) |

134 (33.6) |

| Assisted delivery |

169 (42.5) |

178 (44.5) |

| Fetal distress |

70 (17.7) |

70 (17.7) |

| Intrauterine infection |

4 (1.0) |

8 (2.0) |

| Pre-term |

108 (27.1) |

111 (27.8) |

| Birthweight <2500g |

202 (50.8) |

217 (54.3) |

| SGA baby |

94 (23.7) |

97 (24.3) |

| Asphyxia |

| Mild |

86 (28.8) |

106 (26.5) |

| Moderate |

10 (3.3) |

16 (4.0) |

| Normal |

203 (67.9) |

278 (69.5) |

| Neonatal seizures |

17 (4.3) |

20 (5.0) |

| Respiratory problems |

65 (16.3) |

62 (15.5) |

| Meningitis |

3 (0.8) |

2 (0.5) |

| CNS Malformation |

2 (0.5) |

2 (0.5) |

| Chromosomal anomaly |

2 (0.5) |

2 (0.5) |

After converting the raw mental, motor and Bayley

scores at 1 year and 2 years to percentile rankings, using tables in the

Bayley manual, the same was compared between intervention and control

group. Percentile ranking position 1 denotes lowest raw scores group (<3rd

percentile) and rank 5 denotes highest raw score group (>50th percentile).

The proportion of babies with rank 1 was higher in the control groups and

less in the intervention groups for one year and 2 year motor and mental

scores. On the other hand, the proportion of babies with rank 5 was higher

in the intervention groups and less in the control groups for one year and

2 year motor and mental scores. These differences observed were

statistically significant. In the intervention group, the mean SD of 1

year and 2 year MDI, PDI and Bayley scores were compared by the compliance

score derived from a structured questionnaire, below 31 denoting poor

compliance for home intervention program and above 31 denoting good

compliance. It was observed that as the compliance score increased, there

was a statistically significant increase in the MDI, PDI and Bayley

scores, both at 1 and 2 years.

TABLE II

Mean and SD of Outcome at One Year and Two Year

| |

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

P value |

95% CI |

| |

Intervention

(n=324) |

Control

(n=341) |

|

|

|

One Year |

| MDI |

83.6 |

13.7 |

78.5 |

13.3 |

<0.001 |

3.05, 7.15 |

| PDI |

90.9 |

18.1 |

83.7 |

18.2 |

<0.001 |

4.44, 9.96 |

| Bayley Score |

87.3 |

14.1 |

81.1 |

14.2 |

<0.001 |

4.05, 8.35 |

| Weight (kg) |

8.1 |

1.0 |

7.9 |

1.0 |

<0.001 |

0.17, 0.32 |

| Length (cm) |

72.5 |

2.9 |

72.1 |

3.0 |

0.035 |

2.40, 4.39 |

| Head circumference |

44.4 |

2.3 |

44.3 |

1.7 |

0.580 |

–0.206, 0.406 |

Two Year

|

Intervention

(n=324) |

Control

(n=341) |

|

|

| MDI |

83.1 |

13.9 |

80.3 |

13.4 |

<0.005 |

0.83, 4.77 |

| PDI |

99.9 |

15.6 |

95.8 |

16.6 |

<0.005 |

1.77, 6.43 |

| Bayley Score |

91.5 |

13.0 |

88.0 |

13.7 |

<0.005 |

1.57, 5.43 |

| Weight (kg) |

10.3 |

1.4 |

10.1 |

1.3 |

0.089 |

0.005, 0.39 |

| Length (cm) |

83.5 |

3.6 |

82.4 |

5.2 |

0.002 |

0.45, 1.75 |

| Head circumference |

46.1 |

1.8 |

46.3 |

1.7 |

0.173 |

-0.45, 0.05 |

Multiple regression analysis of the study variables for

the outcome measure of Bayley scores at 1 and 2 year was done separately.

Normal birthweight babies had a significantly higher Bayley score, 5.6

units at one year and 6.2 units at two year, as compared to low

birthweight babies. Babies who did not have neonatal seizures had a

significantly higher Bayley score, 7.9 at one year and 9.9 at two year.

Babies who did not have intrauterine infection had significantly higher

Bayley score, 10.8 units at one year and 11.7 units at two, as compared to

others. After adjusting all these significant risk factors for

development, the babies who had intervention had significantly higher

Bayley scores, 5.8 units at one year and 2.8 units at two year as compared

to control babies. The regression models were statistically significant

both at 1year (R 2 = 15.0%, P<0.0001)

and at 2 years (R2 = 18.7%, P<0.0001). Table III

shows that for an increase of every 500 grams, there is a significant and

consistent increase in mean values of Bayley scores, both at one year and

two year. Similarly, in every birth weight group, the mean values were

higher for the intervention group and these differences were statistically

significant. Similar findings were observed for MDI (P=0.005), PDI

(P=0.001), and length (P=0.002), but not for head circumference (P=0.171)

and weight (P=0.090).

TABLE III

Bayley Scores at the Age of One Year and Two Year

| |

Intervention |

Control |

| |

Mean |

SD |

N |

Mean |

SD |

N |

| Bayley score (1 year)* |

| Below 1500g |

83.8 |

12.0 |

38 |

75.3 |

13.2 |

36 |

| 1501 – 2000g |

83.0 |

16.6 |

65 |

80.5 |

15.0 |

67 |

| 2001 – 2500g |

84.4 |

13.4 |

66 |

76.7 |

13.8 |

71 |

| 2501 – 3000g |

91.2 |

12.9 |

100 |

84.2 |

13.1 |

109 |

| 3001 and above |

91.0 |

12.4 |

54 |

85.0 |

14.0 |

58 |

| Bayley score (2 year) |

| Below 1500g |

89.1 |

13.7 |

43 |

81.9 |

13.6 |

43 |

| 1501 – 2000g |

88.0 |

13.5 |

75 |

86.5 |

14.5 |

82 |

| 2001 – 2500g |

87.9 |

14.1 |

71 |

85.1 |

13.3 |

80 |

| 2501 – 3000g |

94.5 |

10.6 |

109 |

91.9 |

11.9 |

110 |

| 3001 and above |

96.4 |

11.9 |

59 |

91.2 |

14.9 |

61 |

* P value <0.001

Discussion

In spite of a long history of mandatory provision of

early intervention programs for at-risk infants in USA, there are still a

few, who genuinely doubt the usefulness of massive state funding for early

intervention programs(12). The term family-centred early intervention

refers to both a philosophy of care and a set of practices, as both have

been used to guide research, training and service delivery(13). Although,

there is no uniform agreement as to the ideal group of babies who would

benefit maximally from early intervention, the neonatal nursery graduates

would probably form the best captive population for providing early

stimulation.

The sample size estimated was a total of 672 and we

have outcome measurements for 665 babies at one year and 735 babies at two

year. In spite of our best efforts, we were not able to evaluate many

babies who missed their one-year assessment appointment date. Home visits

helped to reduce the dropout rate from 17% at one year to only 8% at two

year. Availability of good objective outcome measurements is crucial for

successful completion of any good trial. Hence the objective

neurodevelopmental outcome measurement of MDI and PDI using

internationally accepted Bayley Scales of Infant Development (BSID), which

has been standardized for the Indian population was appropriately used at

one and two years in this study(10).

The intervention group of babies having a statistically

significant higher score for MDI and PDI at one and two year of age,

suggests that not only early stimulation therapy is effective at one year

but also that effect is present even at two years, without additional

intervention in the second year. The observation that, for increase of

every 500 grams, there is a significant and consistent increase in mean

values of the outcomes at 1 and 2 year and that in every birthweight

group, the mean values are higher for the intervention group, again

suggest that early stimulation is effective across the birth weight

groups. Early intervention programs that go into homes have a greater

chance of reaching high-risk infants, compared with those provided at a

distant centre. Better-educated mothers are more likely to be convinced

about the benefits of such inputs(14). In the Indian context, there is a

potential for introducing home-based early stimulation program through the

Integrated Child Development Services. The data provided shows

conclusively that early intervention is effective and hence the results of

this study may have policy implications.

Acknowledgements

Teena Jacoby, Annie John, Leena ML, Asokan N, Child

Development Centre, Medical College, Thiruvananthapuram.

Contributors: MKC was involved in designing the

study and preparation of the manuscript and will act as guarantor. EP was

involved in quality assurance of data, LJ did the analysis of data. BG,

SM, KP were involved in the data collection.

Funding: Kerala Health Research and Welfare

Society, Government of Kerala, Thiruvananthapuram.

Competing interests: None stated. The findings and

conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not

necessarily represent the views of the funding agency.

|

What This Study Adds?

• CDC model early stimulation therapy done by the

mother at home is effective in improving the developmental status of

neonatal nursery graduates at 1 year and the effect persists at 2

years without additional intervention. |

References

1. Bonnier C. Evaluation of early stimulation programs

for enhancing brain development. Acta Paediatr 2008; 97: 853-858.

2. Nair MKC. Simplified developmental assessment.

Indian Pediatr 1991; 28: 837-840.

3. Scarr-Salapatek S, Margaret L, Williams ML. The

effects of early stimulation on low-birth-weight infants. Child

Development 1973; 44: 94-101.

4. White K, Casto G. An integrative review of early

intervention efficacy studies with at risk children: Implications for the

handicapped. Analysis and Intervention in Developmental Disabilities 1985;

5: 7 –31.

5. Spittle AJ, Orton J, Doyle LW, Boyd R. Early

developmental intervention programs post hospital discharge to prevent

motor and cognitive impairments in preterm infants. Cochrane Database of

Systematic Reviews 2007; 2: CD005495.

6. Nair MKC. Early interventional therapy. Indian J

Pediatr 1992; 59: 657-659.

7. Bonnier C. Evaluation of early stimulation programs

for enhancing brain development. Acta Paediatr 2008; 97: 853-858.

8. Pandit A, Choudhuri S, Bhave S, Kulkarni S. Early

intervention programme through the high risk clinic-Pune experience.

Indian J Pediatr 1992; 59: 675-680.

9. Bayley N. Bayley Scales of Infant Development

Manual. New York: The Psychological Corporation; 1969.

10. Phatak P. Manual for using Bayley Scales of Infant

Development based on Baroda studies and Baroda norms, India : MS

University of Baroda 1973.

11. Nair MKC. Early stimulation CDC Trivandrum Model.

Indian J Pediatr 1992; 59: 663 667.

12. White KR, Mott SE. Conducting longitudinal research

on the efficacy of early intervention with handicapped children. J Div

Early Childhood 1987; 12: 13-22.

13. Bruder MB. Family-centered early intervention.

Early Childhood Special Education 2000; 20: 105-115.

14. de Souza N, Sardessai V, Joshi K, Joshi V, Hughes M. The

determinants of compliance with an early intervention programme for

high-risk babies in India. Child Care Health Dev 2006; 32: 63-72. |

|

|

|

|