M

ovement disorders are

conditions

characterized by involuntary postures and/or movements. It represents a common

presentation in pediatrics and is often a source of clinical and

diagnostic dilemmas [1]. Classically, movement disorders are

classified into hyperkinetic and hypokinetic disorders.

Hyperkinetic disorders are charac-terized by abnormal

involuntary movements and include dystonia, chorea, athetosis,

stereotypies, myoclonus, tics and tremor. Hypokinetic disorders

have in common a paucity of movements and include rare

conditions like parkinsonism [2]. Dystonia and chorea are the

most common forms of movement disorders. In many conditions,

multiple types of movement disorders co-exist and it may be

difficult to identify the type of movements.

There are no estimates on the prevalence of

movement disorders in children or their proportion amongst

pediatric presentations. The exact pathophysiology of movement

disorders is not well understood; however, evidence suggests the

involvement of either basal ganglia or cere-bellar circuits in

most of the conditions, which includes parts of thalamus and

cortex [3]. We, herein, cover common movement disorders with

emphasis on treatable conditions.

DYSTONIA

Dystonia is characterized by sustained or

intermittent muscle contractions causing abnormal, often

repetitive movements, postures, or both. Dystonic movements are

typically patterned (repeatedly involve the same group of

muscles), twisting, and may be tremulous [4]. The postures are

exaggerated on voluntary actions and during stress and subside

during sleep. It may be painful, if severe and continuous. In

the affected body parts, muscle tone is typically variable,

fluctuating from low to high. Children also demonstrate a

splaying approach (spreading of fingers while approaching an

object) and striatal toe sign (intermittent/persistent extension

of the great toe). Sometimes, patients may show the oscillatory

movement of limbs due to intermittent muscle contractions, known

as dystonic tremors [5]. Often dystonia co-exists with

spasticity in children with a severe brain injury like those

with cerebral palsy.

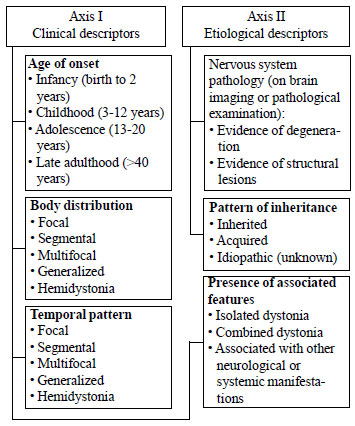

According to a recent consensus [4], each

patient with dystonia should be classified on a set of clinical

(axis I) and etiological (axis II) descriptors (Fig. 1),

as it aids in diagnosis and treatment. Historically, dystonia

has been classified as primary and secondary. Primary refers to

conditions that manifest with pure dystonia, without any

associated other neurological features and without evidence of

pathological abnormalities. All non-primary dystonia are

labelled as secondary. In this review, disorders are grouped

based on the presence of associated features, with an added

category of acute-onset dystonia and paroxysmal dystonia.

|

|

Fig. 1 Classification of

dystonia [4].

|

Isolated Dystonia

Isolated dystonia refers to conditions in

which dystonia is the only motor feature, with an exception of

tremors [4]. Almost all these conditions are genetic in origin

and most children have a period of normal motor development

before the onset of dystonia. Most often there is a focal onset

of dystonia with gradual progression. As most dystonia are

associated with other movement disorders/neurological

comorbidities; with the increasing number of cases described in

literature, entities with isolated dystonia are shrinking.

DYT-TOR1 dystonia is the most common entity

within this group. It an autosomal dominant disorder with onset

in late childhood or adolescence. It starts with focal limb

dystonia, later progressing to generalized dystonia. DYT-HCPA

dystonia starts within first decade with upper limb and cervical

dystonia. Other forms of isolated dystonia can start with

cranial or cervical dystonia (DYT-THAP and DYT-ANO3) [5,6].

Combined Dystonia

This group includes conditions in which

dystonia is accompanied by features of parkinsonism or

myoclonus, in absence of other neurological abnormalities.

Dopa-respon-sive dystonia or Segawa disease (DYT-GCH1) is an

impor-tant condition in this group. It is an autosomal dominant

disorder that presents between 5-10 years of age with limb

dystonia, with more severe involvement of lower limbs. The most

characteristic feature is diurnal variation with children

typically performing motor activities better in the morning or

after a nap. Few children have some associated features of

parkinsonism. Some cases may mimic spastic cerebral palsy.

Dopa-responsive dystonia is a treatable condition and small to

moderate doses of levodopa bring about a complete response. This

also forms the basis of a trial of levodopa in any child with

dystonia [5,7].

Other entities in this group include

myoclonus-dystonia (DYT-SGCE, DYT-ANO3, DYT-TOR1A or

DYT-CACNA1B) and rapid-onset dystonia-parkin-sonism

(DYT-ATP1A3). Myoclonus-dystonia is genetically heterogeneous

and can present any time after infancy with upper body myoclonus

and limb dystonia. In patients with rapid onset

dystonia-parkinsonism, symptoms are trigge-red with emotional or

physical stress and there is often a stuttering course [5,8].

Associated With Other Manifestations

Children with cerebral palsy, and

neurodegenerative and metabolic disorders form a major part of

this group. Dystonia is often a feature in children with

bilirubin induced neurological damage (BIND) and severe

hypoxic-ischemic brain injury at birth.

Monoamine neurotransmitter disorders are a

hetero-geneous group of conditions that result from deficiency

of cerebral dopamine, serotonin, or both. Most patients become

symptomatic in infancy or early childhood with varying

combination of developmental delay, encephalo-pathy, epilepsy,

spasticity, dystonia, chorea and autonomic dysfunction. Some

children may show diurnal variation. Analysis of CSF

neurotransmitter levels aid in diagnosis. Dopa-responsive

dystonia is also a monoamine neuro-transmitter disorders but has

fewer manifestations [9]

Progressive dystonia and spasticity in early

childhood may be a manifestation of hypomyelinating

leukoence-phalopathies like Pelizaeus Merzbacher syndrome, which

typically presents with pendular nystagmus, developmental delay

and hypotonia in early infancy. Dystonia and ence-phalopathy can

be seen in organic academia and mitochondrial encephalopathies

[5]. Pantothenate kinase–associated neurodegeneration (PKAN)

presents around 3 years of age with clumsiness and gait

abnormality due to lower limb dystonia and spasticity, along

with pigmentary retinopathy [10].

In children with onset of dystonia in late

childhood or adolescence, Wilson disease is an important

differential. Besides dystonia, tremors, dysphagia, dysarthria,

drooling and walking difficulty may be present. Almost all

patients have Kayser-Fleischer rings on eye examination [11].

Acute-Onset Dystonia and Paroxysmal Dystonia

Acute-onset dystonia can be a manifestation

of adverse effects of drugs, stroke, encephalitis, and

functional disorder. Anti-emetics (like metoclopramide) and

antipsychotic drugs (like haloperidol and risperidone) are most

commonly implicated in drug induced dystonia [12]. Dystonia is a

common manifestation of neurotuberculosis and Japanese

encephalitis.

Some genetic conditions manifest with

episodic involuntary movements lasting from seconds to hours,

most often with well-defined triggers. In between the episodes,

the child is usually normal. This group includes conditions like

Paroxysmal kinesigenic dystonia (triggered by sudden movement),

Paroxysmal non-kinesigenic dystonia (triggered by stress,

alcohol, etc.) and Paroxysmal exertional dystonia (triggered by

exercise) [5,13].

Glut-1 deficiency is a rare condition that

occurs due to a deficiency of glucose transporter type 1 in the

brain. It manifests as absence epilepsy, ataxia, developmental

delay and paroxysmal exertional dystonia in early childhood. Low

CSF glucose is the biochemical hallmark and symptoms show a

dramatic response to ketogenic diet [14].

Status Dystonicus

Status dystonicus, or dystonic storm is a

life-threatening condition characterized by frequent or

continuous severe episodes of generalized dystonic spasms.

Although it can occur in any condition causing dystonia, it is

most often seen in children with cerebral palsy and

neurodegenerative disorders. Infections (febrile illnesses) and

other stressors act as triggers. Severe spasm may result in

pain, dehydration, respiratory compromise, rhabdomyolysis and

acute renal failure [15,16].

Clinical Approach

While evaluating a child with dystonia,

ascertain the age of onset, distribution (focal or generalized),

temporal pattern (i.e. diurnal, static, or progressive) and

associated neurological and systemic abnormalities. An important

clue to etiology is that primary dystonia begins as action

dystonia and can persist in kinetic form while secondary or

symptomatic dystonia often begins as sustained postures or tonic

form. Fig. 2 provides an algorithm for clinical

diagnosis.

|

|

Fig. 2 Clinical approach to

diagnosis of dystonia in children.

|

Eye examination and brain MRI help in

narrowing the differential diagnosis. Eye evaluation should be

focused on KF ring, optic atrophy and retinitis pigmentosa. MRI

is essentially normal in primary dystonia (DYT dystonia). MRI

has diagnostic significance in Wilson disease (T2 hyperintensity

in basal ganglia), PKAN (‘Eye of the Tiger’ sign in globus

pallidus), hypomyelinating disorders (white matter changes) and

Japanese encephalitis (bilateral thalamic involvement) [5].

Metabolic screening is warranted in a child

with encephalopathy. In a child with fluctuating weakness, CSF

analysis will help in ruling out neurotransmitter defect and

Glut-1 deficiency. A therapeutic trial of levodopa is

recommended for all children; although, very few dystonias are

levodopa responsive, and there is a lot of variability in dose

range for children who do respond [17]. In patients with

suspected genetic etiology, dystonia gene panel testing may

provide the definitive diagnosis. With the increasing

availability of whole exome sequencing (WES), the diagnostic

process can be significantly shortened [18].

Management

The drugs used in management of dystonia are

detailed in Table I. In most patients with severe

dystonia, outcomes are unsatisfactory. Neurosurgical procedures

like deep brain stimulation (DBS) and intra-thecal baclofen pump

(ITB) can be used in refractory dystonia. DBS has shown

substantial benefits in children with primary dystonia, whereas

in children with dyskinetic cerebral palsy, mild to moderate

improvement occurs [22].

|

The management of status dystonicus is

multi-pronged. Patients should be monitored for renal functions,

creatine kinase, blood gas, and urine and/or blood myoglobin

levels. Addressing the precipitant and providing supportive care

(hydration, respiratory support, hemodialysis etc.) is

important. The mainstay of therapy is careful use of sedatives.

Chloral hydrate is recommended as initial therapy (30-100 mg/kg

orally every 3-4 hours). Most patients need the addition of

clonidine (initial dose 3µg/kg 8 hourly, can be increased up to

3-5 µg/kg/hour given as 3-hourly dose. In unresponsive patients,

continuous midazolam infusion may be effective. Besides

sedatives, dystonia specific drugs like trihexyphenidyl,

pimozide and tetrabenazine are also required. In patients with

poor response to drugs, DBS should be offered. The role of ITB

is less clear but may be more effective in patients with

concomitant spasticity [15-16].

TREMORS

Tremors refer to rhythmic, regular

back-and-forth or oscillatory movement of part of the body about

a joint axis [23]. Tremors are classified as resting tremors and

action tremors.

Resting tremors are quite rare in childhood;

however, can be seen in juvenile parkinsonism, Wilson disease,

PKAN, Huntington disease and midbrain lesions [24]. Psychogenic

and dystonic tremors can also be present at rest. In context to

developing countries, infantile tremor syndrome (ITS) is an

important cause. ITS typically manifest in exclusively breastfed

infants of vegetarian mothers, with developmental

delay/regression, anemia, skin hyperpigmentation, and tremors.

Tremors usually start with upper limbs and subside during sleep.

Almost all patients have vitamin B12 deficiency and respond to

supplementation [25].

Action tremors are further classified as

simple kinetic, intention, isometric, task-specific and

postural. Simple kinetic tremor is present during simple limb

movements. It is typically a feature of essential tremor.

Essential tremor affects only the upper limbs and family history

is present in many patients. Usually, the onset is in adulthood

or later, but can sometimes occur in children. A duration of 3

years is required for diagnosis [24]. Functional and

drug-induced tremors can also be simple kinetic. In intention

tremor, the amplitude of tremor increases as the body part is

reaching a visual target. It is characteristically seen in

cerebellar disorders but can also be present in midbrain lesions

[24,26].

Postural tremor is seen when a body part is

held in a position against gravity. Each individual has some

physiological postural tremor, best appreciated in an

outstretched hand. This can be exaggerated by stress, fasting,

illness, strenuous exercise, thyrotoxicosis and drugs like

salbutamol and valproate. Isometric dystonia occurs during

sustained muscle contraction against stationary objects like

while holding a book. Exaggerated physiological tremor and

essential tremor can be isometric. Task-specific dystonia is

related to specific tasks like writing or playing an instrument

[24,26].

Clinical Approach and Management

While evaluating a child with tremors, note

the onset, aggravating and relieving factors, drug history and

family history. Examine for tremors along with muscle tone and

gait pattern. Presence of associated dystonia points towards

conditions like PKAN and Wilson disease. Sudden onset and offset

and marked variation in the semiology favours psychogenic

tremor. Some patients with only dystonia may show tremulous limb

movements, referred as dystonic tremors. Other conditions that

mimic tremors include jitteriness, seizures, myoclonus,

shuddering attacks, and stereotypic movements.

Investigations will depend on the suspected

etiology. Thyroid function should be done for enhanced

physiological tremors. Neuroimaging and other relevant workup

should be done for suspected cerebellar disorder or a

neurodegenerative condition. For ITS, vitamin B12 levels should

be obtained.

Propanolol is recommended in severe cases of

essential tremors and patients with physiological tremors who

have functional or social limitations. Other drugs that are

effective in essential tremors include primidone and

benzodiazepines [24,26].

CHOREA

Chorea refers to involuntary, irregular,

non-repetitive dance-like movements of the body parts that

appear to flow from one muscle group to another without

following any pattern. Children with chorea appear hyperactive

or fidgety. The ability to perform voluntary movements remains

unimpaired. Many grown-up children with chorea transform the

choreiform movement into a voluntary act in order to mask it,

referred to as parakinesia [27]. Patients with chorea have motor

impersistence, which refers to the inability to maintain

sustained postures like keeping tongue protruded or arms

outstretched [28]. Like all movement disorders, chorea also

disappears during sleep.

Chorea with large amplitude, rapid flinging

movements, usually affecting the proximal joints is referred as

ballism [23]. Some patients have slower continuous, involuntary

writhing movements affecting the distal upper extremities,

referred to as athetosis. Athetosis is a distinct movement

disorder; however, it co-exists with chorea and ballism, and

represents a clinical spectrum [23].

Chorea due to a known or presumed genetic

cause is referred as primary chorea. Chorea resulting from

infections, injuries, infiltrative conditions or immune mediated

disorders affecting the brain is called as secondary chorea.

Primary Chorea

Huntington disease: It is an

autosomal dominant disorder that manifest in late adulthood with

chorea, dystonia, psychiatric disturbances, and dementia.

Juvenile Huntington disease is rare and more commonly present

with dystonia, parkinsonism, behavior problems, and cognitive

deterio-ration, rather than chorea [29].

Ataxia-telangiectasia:

Choreoathetosis involving the upper extremities is an early

feature of Ataxia-Telangiectasia, however; it is often mild.

Ataxia that develops by 3-6 years of age is the prominent

manifestation and brings the child to medical attention [30].

Benign hereditary chorea: It is an

autosomal dominant condition with median age of onset of 2.5-3

yrs. The intelligence is normal and the condition tends to

become static after the first decade with improvement in

adulthood. Some patients have accompanying hypothyroidism and

pulmonary disease [31].

Others: In some conditions like

spinocerebellar ataxia type 17, ataxia with oculomotor apraxia

and Friedreich ataxia, chorea may be an early feature, though

ataxia predomi-nantes as the disease progresses. Paroxysmal

movement disorders present with intermittent episodes of chorea

and dystonia [13]. There is a growing list of genetic etiologies

of chorea, with mutation in ADCY5 and PDE10A being

important cause of childhood onset movement disorders [32].

Secondary Chorea

Sydenham chorea: This is the most

common cause of acute-onset chorea in children. It is a late

manifestation of acute rheumatic fever and affects children aged

5-15 years. The chorea mainly involves the upper extremities and

at times there may be wide flinging movements (ballism) [27].

The other manifestations include hypotonia, personality changes,

emotional lability, obsessive-compulsive symptoms and

attention-deficit [33]. Diagnosis is mostly clinical as the

laboratory evidence of recent streptococcal infection is often

lacking.

Other immune-mediated conditions:

Chorea may be the presenting or associated feature in children

with systemic lupus erythematosus associated with

anti-cardiolipin antibodies. Chorea may be a feature of

autoimmune encephalitis, the other manifestations being

seizures, encephalopathy and neuropsychiatric disturbances [34].

Chorea associated with brain injury:

Children with dyskinetic cerebral palsy may have chorea,

besides dystonia. Chorea may be a part of neurological sequelae

after viral encephalitis or stroke.

Drug-induced chorea: Certain drugs like

trihexyphenidyl, levodopa, phenytoin and carbamazepine can

precipitate chorea in a child with other types of movement

disorders or brain injury [27].

Clinical Approach and Management

The history should include perinatal events,

previous infections and associated symptoms. The child should be

examined in a distraction-free environment to note the presence

of chorea and any other movement disorder. Video recording of

movements by parents at home help in characterization of

movements. Child should be examined for motor impersistence,

including inability to keep tongue protruded (darting tongue),

maintain sustained arm grip on examiners fingers (milkmaid’s

grip) and keep upper limbs extended above the head with palms

facing inwards [28]. A clinical approach to diagnosis is

discussed in Fig. 3. Diagnostic work-up depends on the

suspected etiology.

|

|

Fig. 3 Clinical approach to

diagnosis of chorea in children.

|

Atypical antipsychotics like olanzapine or

risperidone are effective in the management of acute onset

chorea or acute exacerbation. Tetrabenazine and anti-epileptics

like valproic acid and carbamazepine are alternatives. Valproic

acid can be tried in patients who fail to respond to

anti-psychotics. Patients with severe forms of Sydenham chorea

or those unresponsive to antipsychotics may respond to

intravenous immunoglobulin or corticosteroids [35,36]. In

patients with Huntington disease, the preferred drugs are

tetrabenazine, olanzapine, risperidone, and recently,

deutetranenazine [37].

TIC DISORDER

Tics refer to repeated, individually

recognizable, intermittent movements, movement fragments, or

sounds that are almost always briefly suppressible and are

usually associated with awareness of an urge to perform the

movement [23]. The premonitory urge to carry out the movement is

often distressing to older patients. Tics can manifest after 5-6

years of age; however, adolescents are most severely affected.

Tics may affect the social functioning of an individual and

cause embarrassment. Tics are presumed to be genetic because of

the high concordance rate between twins (53%); however, the

genetic loci are not known. Mostly, tic is a primary problem,

rarely it may be part of other neurological disorders [38,39].

Tics are classified based on type (motor or

vocal) and duration. A tic can be simple (like eye blinking,

head jerking, facial grimacing, brief vocalization, throat

clearing, and sniffing) or complex (like obscene gestures or

copropraxia, posturing, echolalia, and coprolalia). A tic

disorder that has been there for less than a year or subsides

within a year is labelled as transient tic disorder. Those

lasting more than a year are called chronic and include Tourette

syndrome and persistent motor or vocal tic disorder [38,39].

Tourette syndrome is defined by presence of

multiple motor tics (at least two distinct ones) and one or more

vocal tics which wax and wane, but have persisted for more than

one year [39]. It is commonly associated with behavioral

disorders like attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD),

obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), anxiety, mood disorders and

disruptive behavior disorders. About two-third of individuals

meet the criteria of ADHD or OCD at some time during the course

of disease [40]. Persistent motor or vocal tic disorder is

defined as having a single or multiple motor or vocal tics which

may wax and wane but have persisted for more than one year. Tics

may sometimes be part of autism spectrum disorder and

neurodegenerative disorders.

Management

Comprehensive behavioral intervention for

tics (CBIT) is efficacious in reducing tics and is recommended

as the initial treatment. CBIT program consists of habit

reversal therapy, relaxation training, and functional

interventions to address situations that sustain or worsen tics.

If CBIT is ineffective or unavailable, pharmacotherapy can be

used. A variety of drugs are effective including alpha-agonists

like clonidine and guanfacine, anti-psychotics like haloperidol,

pimozide and risperidone and anti-epileptics like topiramate.

Alpha-agonists have lower efficacy than anti-psychotics but are

preferred due to favorable side effect profile. Alpha-agonists

also improve the behavioral comorbidities [41,42].

MYOCLONUS AND STARTLE SYNDROMES

Myoclonus is a sudden, brief, shock-like

involuntary movement of the body. It can involve a single body

part, one half of body or whole body. Myoclonus is mostly

spontaneous, but in some conditions it can be induced by an

action or sensory stimuli like light, sound or touch [1]

Hiccups and sleep starts are considered as

physiological forms of myoclonus. Sleep starts occur during

sleep initiation, manifesting with a sense of falling [1].

Benign neonatal sleep myoclonus and benign myoclonus of early

infancy are viewed as developmental conditions (detailed later)

[47]. Many young children manifest myoclonus during febrile

episodes. Myoclonus can be epileptic as in some epileptic

syndromes (like West syndrome and juvenile myoclonic epilepsy)

and neurodegenerative disorders [1].

Opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome (OMS) is a rare

immune-mediated condition that manifests acutely or sub-acutely

in toddlers with chaotic multi-directional conjugate eyes

movements (opsoclonus), myoclonus, ataxia, irrita-bility and

sleep disturbance. Approximately half of the patients have

associated neural crest tumors (mostly a neuroblastoma). A

combination of pulse corticosteroids or ACTH and intravenous

immunoglobulins are recommen-ded as the initial treatment.

Surgical tumor resection has no effect on the symptoms in the

majority [43,44].

Startle syndromes are conditions

characterized by exaggerated startle in response to a sound,

movement and touch. Hereditary hyperekplexia is an autosomal

dominant disorder that manifest in infants and young child with

exaggerated startle associated with tonic stiffness of the body,

with repeated falls. A bedside test involves demons-tration of

non-habituating head retraction in response to repeated tapping

of the tip of the nose. With increasing age, the severity

improves; however, it can be precipitated by stress or fatigue.

Most children respond to clonazepam in the dose range of 0.01 -

0.1 mg/kg/day [45,46].

Other conditions associated with exaggerated

startle are other forms of hyperekplexia, post-hypoxic and

post-traumatic encephalopathy, encephalitis, brainstem

dysfunc-tion and neurodegenerative disorders like GM1

ganglio-sidosis and Tay-Sach disease [46].

STEREOTYPIC MOVEMENT DISORDERS

Stereotypies refer to repetitive,

non-functional, patterned movements and/or vocalizations that

can be suppressed by distraction. Simple stereotypies like leg

shaking, hair twirling, body rocking, head banging, and humming

are considered as part of normal behavior. Complex stereotypies

like hand flapping, oro-facial movement and eye-poking, which

interfere with functions or are self-injurious are considered as

abnormal [47]. Complex stereotypies are sometimes seen in

typically developing children, but tend to remain stable or

regress with age. More commonly, they are associated with

conditions like autism spectrum disorders, intellectual

disability, Rett syndrome, Down syndrome, phenylketonuria,

visual or auditory impairment, and acquired brain injury

[47,48]. In children with blindness, stereotypies are seen in

more than two-third of patients, the common ones are body

rocking, repetitive handling of objects, hand and finger

movements, eye pressing and eye poking [49]. Behavior therapy

(habit reversal therapy) is the mainstay of treatment for

stereotypies. Drugs like risperidone and fluoxetine have role in

patients with autism [47,48].

PARKINSONISM

Parkinsonism is a hypokinetic movement

disorder, characterized by presence of resting tremors,

bradykinesia (paucity or slowness of movements), rigidity (lead

pipe type) and postural instability. It can occur in conditions

like Huntington disease and Wilson disease, or can be an adverse

effect of tetrabenzine. Juvenile Parkinson disease is a rare

genetic disorder that manifest with parkinsonism and leg

dystonia [50].

FUNCTIONAL MOVEMENT DISORDERS

It refers to involuntary movements that

result from abnormal mental state or condition, and are

incompatible with recognized neurological and medical

conditions. The common presentations in children are tremors,

dystonia and myoclonus; others being gait disturbances, tics,

chorea and tetany. Many children have identifiable precipitating

factors like school examination, bullying, injury, illness,

sexual abuse of the child or family member, parental discord or

domestic violence, and death of a close relative [51-53]. It is

mostly seen in children above 6-7 years and is more common in

girls.

The diagnosis is suggested by a history of

sudden onset, marked variability of symptoms, and sustained

spon-taneous remissions. Examination often shows symptom

variation, incongruous movements, distraction during spontaneous

speech and behavior, the appearance of symptoms, or worsening

during attention and production or suppression of symptoms on

examiner’s suggestion [51]. In psychogenic tremor, entrainment

or alteration with rhythmic tapping of another body part is

seen. For management, behavior therapy and relaxation techniques

are usually employed. Parental education and counseling are

important [53].

DEVELOPMENTAL AND BENIGN MOVEMENT DISORDERS

These are a group of conditions that manifest

during specific developmental phases of childhood in absence of

associated neurological features. They are considered as

manifestation of subtle modification in the developing brain and

have a favorable outcome [54]. The common disorders are detailed

in Table II.

CONCLUSION

Movement disorders in children comprise of a

heterogeneous group of conditions with diverse etiologies. The

predominant conditions are dystonia, chorea, tics and tremors.

Multiple movement disorders coexist in many conditions and often

create diagnostic confusion. Presence of other neurological and

systemic manifestations helps in narrowing the differential

diagnosis. Neuroimaging and genetic studies enables accurate

diagnosis. The management of these conditions is often

challenging. One should always look for easily treatable

conditions like dopa-responsive dystonia and infantile tremor

syndrome.

Contributors: All authors contibuted to

the manuscript preparation, and final approval.

Competing interests: None stated;

Funding: None.

REFERENCES

1. Delgado MR, Albright AL. Movement

disorders in children: definitions, classifications, and

grading systems. J Child Neurol. 2003;18:S1-8.

2. Fahn S. Classification of movement

disorders. Mov Disord. 2011;26:947-57.

3. Wichmann T. Pathophysiologic Basis of

Movement Disorders. Prog Neurol Surg. 2018;33:13–24.

4. Albanese A, Bhatia K, Bressman SB, et

al. Phenomenology and classification of dystonia: a

consensus update. Mov Disord. 2013;28:863-73.

5. Meijer IA, Pearson TS. The twists of

pediatric dystonia: Phenomenology, classification, and

genetics. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2018;25:65-74.

6. Zorzi G, Zibordi F, Garavaglia B, et

al. Early onset primary dystonia. Eur J Paediatr Neurol.

2009;13:488-92.

7. Segawa M. Autosomal dominant GTP

cyclohydrolase I (AD GCH 1) deficiency (Segawa disease,

dystonia 5; DYT 5). Chang Gung Med J. 2009;32:1-11.

8. Balint B, Bhatia KP. Isolated and

combined dystonia syndromes - an update on new genes and

their phenotypes. Eur J Neurol. 2015;22:610-617.

9. Kurian MA, Gissen P, Smith M, et al.

The monoamine neurotransmitter disorders: an expanding range

of neurological syndromes. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:721-33.

10. Hayflick SJ, Kurian MA, Hogarth P.

Neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation. Handb Clin

Neurol. 2018;147:293-305.

11. Roberts EA, Socha P. Wilson disease

in children. Handb Clin Neurol. 2017;142:141-56.

12. Goraya JS. Acute movement disorders

in children: experience from a developing country. J Child

Neurol. 2015;30:406-11.

13. Waln O, Jankovic J. Paroxysmal

movement disorders. Neurol Clin. 2015;33:137 152.

14. Koch H, Weber YG. The glucose

transporter type 1 (Glut1) syndromes. Epilepsy Behav.

2019;91:90-93.

15. Allen NM, Lin JP, Lynch T, et al.

Status dystonicus: a practice guide. Dev Med Child Neurol.

2014;56:105-112.

16. Lumsden DE, King MD, Allen NM. Status

dystonicus in childhood. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2017;29:674-82.

17. Maas RPPWM, Wassenberg T, Lin JP, et

al. l-Dopa in dystonia: A modern perspective. Neurology.

2017;88:1865-1871.

18. Powis Z, Towne MC, Hagman KDF, et al.

Clinical diagnostic exome sequencing in dystonia: Genetic

testing challenges for complex conditions. Clin Genet.

2020;97:305-11.

19. Luc QN, Querubin J. Clinical

Management of Dystonia in Childhood. Paediatr Drugs.

2017;19:447 61.

20. Fehlings D, Brown L, Harvey A, et al.

Pharmacological and neurosurgical interventions for managing

dystonia in cerebral palsy: a systematic review. Dev Med

Child Neurol. 2018;60:356-66.

21. Hegenbarth MA; American Academy of

Pediatrics Committee on Drugs. Preparing for pediatric

emergencies: drugs to consider. Pediatrics. 2008;121:433-43.

22. Elkaim LM, De Vloo P, Kalia SK, et

al. Deep brain stimulation for childhood dystonia: current

evidence and emerging practice. Expert Rev Neurother.

2018;18:773-84.

23. Sanger TD, Chen D, Fehlings DL, et

al. Definition and classification of hyperkinetic movements

in childhood. Mov Disord. 2010; 25:1538-549.

24. Miskin C, Carvalho KS. Tremors:

Essential Tremor and Beyond. Semin Pediatr Neurol.

2018;25:34 41.

25. Goraya JS, Kaur S. Infantile tremor

syndrome: A review and critical appraisal of its etiology. J

PediatrNeurosci. 2016;11:298 304.

26. Prasad M, Ong MT, Whitehouse WP.

Fifteen minute consultation: tremor in children. Arch Dis

Child Educ Pract Ed. 2014;99:130 134.

27. de Gusmao CM, Waugh JL. Inherited and

acquired choreas. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2018;25:42 53.

28. Kojoviæ M, Bhatia KP. Bringing order

to higher order motor disorders. J Neurol.

2019;266:797-805.

29. Roos RA. Huntington’s disease: A

clinical review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;5:40.

30. Pearson TS. More than ataxia:

Hyperkinetic movement disorders in childhood autosomal

recessive ataxia syndromes. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov.

2016;6:368.

31. Peall KJ, Kurian MA. Benign

hereditary chorea: An update. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov.

2015;5:314.

32. Carecchio M, Mencacci NE. Emerging

monogenic complex hyperkinetic disorders. Curr Neurol

Neurosci Rep. 2017;17:97.

33. Punukollu M, Mushet N, Linney M, et

al. Neuropsychiatric manifestations of Sydenham’s chorea: A

systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2016;58:16-28.

34. Cardoso F. Autoimmune choreas. J

Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2017;88:412-17.

35. Walker KG, Wilmshurst JM. An update

on the treatment of Sydenham’s chorea: The evidence for

established and evolving interventions. Ther Adv Neurol

Disord. 2010;3:301-9.

36. Dean SL, Singer HS. Treatment of

sydenham’s chorea: A review of the current evidence. Tremor

Other Hyperkinet Mov. 2017;7:456.

37. Coppen EM, Roos RA. Current

pharmacological approaches to reduce chorea in Huntington’s

disease. Drugs. 2017;77:29-46.

38. Leckman JF. Phenomenology of tics and

natural history of tic disorders. Brain Dev.

2003;25:S24-S28.

39. Fernandez TV, State MW, Pittenger C.

Tourette disorder and other tic disorders. Handb Clin

Neurol. 2018;147:343-54.

40. Hirschtritt ME, Lee PC, Pauls DL, et

al. Lifetime prevalence, age of risk, and genetic

relationships of comorbid psychiatric disorders in Tourette

syndrome. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72: 325-33.

41. Pringsheim T, Okun MS, Müller-Vahl K,

et al. Practice guideline recommendations summary: Treatment

of tics in people with Tourette syndrome and chronic tic

disorders. Neurology. 2019;92:896-906.

42. Quezada J, Coffman KA. Current

approaches and new developments in the pharmacological

management of Tourette synd-rome. CNS Drugs. 2018;32:33-45.

43. Desai J, Mitchell WG. Acute

cerebellar ataxia, acute cerebellitis, and

opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome. J Child Neurol.

2012;27:1482-8.

44. Hero B, Schleiermacher G. Update on

pediatric opsoclonus myoclonus syndrome. Neuropediatrics.

2013;44:324-9.

45. Saini AG, Pandey S. Hyperekplexia and

other startle syndromes. J Neurol Sci. 2020 Sep

15;416:117051.

46. Bakker MJ, van Dijk JG, van den

Maagdenberg AM, et al. Startle syndromes. Lancet Neurol.

2006;5:513-24.

47. Katherine M. Stereotypic Movement

Disorders. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2018;25:19-24.

48. Barry S, Baird G, Lascelles K, et al.

Neurodevelopmental movement disorders - an update on

childhood motor stereotypies. Dev Med Child Neurol.

2011;53:979-985.

49. Fazzi E, Lanners J, Danova S, et al.

Stereotyped behaviors in blind children. Brain Dev.

1999;21:522-28.

50. Niemann N, Jankovic J. Juvenile

parkinsonism: Differential diagnosis, genetics, and

treatment. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2019;67:74-89.

51. Hallett M. Functional (psychogenic)

movement disorders - Clinical presentations. Parkinsonism

Relat Disord. 2016;22: S149-S152.

52. Harris SR. Psychogenic movement

disorders in children and adolescents: an update. Eur J

Pediatr. 2019;178:581-585.

53. Pandey S, Koul A. Psychogenic

movement disorders in adults and children: A clinical and

video profile of 58 Indian patients. Mov Disord Clin Pract.

2017;4:763-67.

54. Bonnet C, Roubertie A, Doummar D, et al. Developmental

and benign movement disorders in childhood. Mov Disord.

2010;25:1317-3.