antrell syndrome is a

rare, usually lethal, congenital malformation [1]. In the

complete form, five anomalies exist, namely a midline

supra-umbilical abdominal wall defect, a sternal defect, an

anterior diaphragmatic defect, a diaphragmatic pericardial

defect and a congenital heart defect. However, the extent of

individual defects and their combination varies considerably;

broad spectrum of associated cardiac abnormalities have been

reported in most cases. We describe a neonate presenting with a

pulsatile umbilical swelling and cyanosis since birth, later

confirmed to be due to Cantrell syndrome.

A full term male neonate with uneventful

antenatal and perinatal course, born to a primigravida mother by

normal vaginal delivery, was noted to have a pulsatile umbilical

mass immediately after birth. Antenatal second trimester

sonographic scans were reported normal, but detailed anomaly

scan was not done. Baby was seen at our institute on day seven

of life. He was feeding well, had a capillary filling time <3

second and normal urine output. Examination revealed tachycardia

with a heart rate of 200 beats per minute, and central cyanosis

(oxygen saturation 85% in room air). A peculiar mass arising

from just above the umbilical stump, measuring 5×2×2 cm was

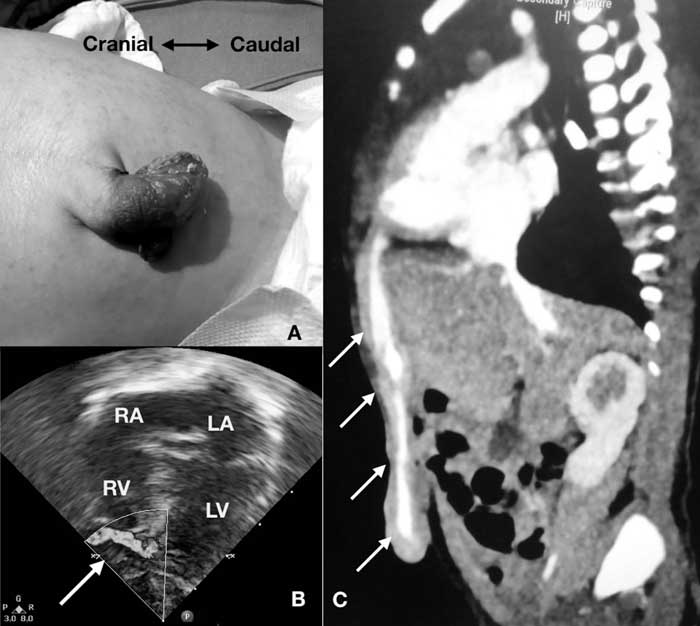

noted. The mass enlarged with each cardiac systole (Fig.

1a). It was covered with skin on its dorsal aspect but its

ventral aspect was devoid of skin. On palpation, the structure

had a forceful impulse and auscultation revealed a loud

to-and-fro murmur over the mass. Cardiovascular examination

revealed no evidence of heart failure, wide split second heart

sound with a soft pulmonic component and a grade 3/6 ejection

systolic murmur at left upper sternal border. A midline defect

was palpable in the anterior abdominal wall.

|

|

Fig. 1 (a) Clinical

photograph of umbilical swelling; (b) echocardiogram in

four chamber view showing a vascular channel (white

arrow) arising from left ventricle apex; (c) CT

angiographic section in sagittal view showing the

abnormal vascular channel (white arrows) arising from

left ventricle apex.

|

Electrocardiogram revealed atrial flutter

with ventricular rate of 200/min. Chest radiograph showed situs

solitus, levocardia, normal sized heart and pulmonary oligemia.

Ultrasound and Doppler evaluation of the mass revealed normal

umbilical arteries, with a connection between umbilical vein and

left ventricle through falciform ligament, suggestive of left

ventricular diverticulum. Echocardiogram showed double outlet

right ventricle with infundibular pulmonary stenosis. There was

a tubular structure arising from apex of left ventricle which

had a to-and-fro Doppler flow through it (Fig. 1b).

Computed tomography (CT) angiography revealed a dilated vascular

channel beginning from the umbilical outpouching and travelling

cranially within the anterior abdominal wall and along the

falciform ligament to drain into the left ventricular apex

through a 2 mm opening. There were multiple stenosis throughout

its course, confirming the diagnosis of left ventricular

diverticulum (Fig. 1c). Defect in anterior

diaphragm was present, but there was no associated sternal

defect.

In view of atrial flutter, patient was

started on propranolol and digoxin, and good heart rate control

was achieved. After discussion with the cardiac surgical team,

it was decided to close the left ventricular diverticulum, the

cardiac lesion to be addressed later, since the oxygen

saturation of the baby stayed above 85%. Left anterolateral

thoracotomy was done and the fistulous tract arising from

anterior most part of the left ventricular apex was identified.

It was double clamped and divided and both ends were sutured.

Defect in diaphragm was closed. The umbilical swelling was

excised and the skin repaired. Patient had a smooth

post-operative course and recovered well. The cardiac rhythm

reverted to sinus rhythm on postoperative day 6. He was

discharged on ninth post-operative day. Digoxin was stopped at

six-week follow-up. Currently, at one-year follow up, baby is

doing well, his oxygen saturation is 80% and he is in sinus

rhythm. He is planned for Glenn surgery in view of non-committed

muscular VSD, and is awaiting the same.

Only 250 cases of Cantrell syndrome have been

reported in the literature [2]. It has high morbidity and

mortality, with more than half of patients dying, many despite

surgery [3]. Abnormal migration of the splanchnic and somatic

mesoderm (which affects the development of the heart and the

major vessels) with premature breakage of the chorion or

vitelline sac at about day 14 to 18 of gestation, may lead to a

mid-line defect [4] Congenital cardiac malformations are

associated in majority, ventricular septal defect is the

commonest abnormality. Association with double outlet right

ventricle has also been previously reported [5].

Over 70% of patients with left ventricular

diverticulum have Cantrell syndrome. The diverticulum originates

from the left ventricular apex in these cases and may be

associated with umbilical hernia and complex cardiac

abnormalities. Ventricular aneurysm must be differentiated from

diverticulum. A narrow mouth and synchronous contractility

characterize a diverticulum. On the other hand, aneurysms show

akinesia or paradoxic contractility of the outpouching, which is

asynchronous with the rest of heart.

Early surgical repair is indicated in cases

of left ventricular diverticulum, as it may rupture

spontaneously, thrombose or produce arrhythmias. It is generally

recommended that the midline thoraco-abdominal defect is treated

first and heart defects be corrected later [6]. We present this

case in view of the interesting presentation in a neonate with a

pulsatile umbilical swelling and cyanosis, and a good outcome

after surgery.

REFERENCES

1. Cantrell JR, Haller JA, Ravitch MM. A

syndrome of congenital defects involving the abdominal wall,

sternum, diaphragm, pericardium and heart. Surg Gynecol Obstet.

1958;107:602-14.

2. Jnah AJ, Newberry DM, England A. Pentalogy

of Cantrell: Case report with review of the literature. Adv

Neonatal Care. 2015;15:261-8.

3. O’gorman CS, Tortoriello TA, McMahon CJ.

Outcome of children with pentalogy of Cantrell following cardiac

surgery. Pediatr Cardiol. 2009;30:426-30.

4. Amato JJ, Douglas WI, Desai U, Burke S.

Ectopia cordis. Chest Surg Clin North Am. 2000;10:297-316.

5. Singh N, Bera ML, Sachdev MS, Aggarwal N,

Joshi R, Kohli V. Pentalogy of Cantrell with left ventricular

diverticulum: A case report and review of literature. Congenital

Heart Dis. 2010;5:454-7.

6. Williams AP, Marayati R, Beierle EA. Pentalogy of

Cantrell. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2019;28:106-10.