|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2020;57:801-804 |

|

Pharmaceutical

Excipient Exposure in a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit

|

|

Sara Nasrollahi, 1

Neelathahalli Kasturirangan Meera1

and Sunil Boregowda2

From Department of 1Pharmacy Practice, Visveswarapura Institute of

Pharmaceutical Sciences, and 2Department of Pediatrics, KIMS Hospital

and Research Centre, Bangalore, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Sara Nasrollahi, Department of Pharmacy

Practice, Visveswarapura Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences,

Bangalore, India.

Email: [email protected]

Received: August 20, 2019;

Initial review: December 30, 2019;

Accepted: April 22, 2020.

|

Objective: To study the excipients exposure among neonates in a

neonatal intensive care unit. Method: Prospective observational

study was conducted from January, 2017 to June, 2019. Details of

administered drugs were collected from the hospital case files. List of

excipients of formulations and their quantities were collected from

package insert leaflets or by contacting the manufacturers. Excipients

were grouped into four categories based on available safety data.

Calculated daily exposures to the excipients (mg/kg/day) were compared

with adult acceptable daily intake. Results: More than half of

the included 746 neonates were exposed to harmful excipients. 12.3% and

12.7% of neonates received higher than acceptable daily intake of sodium

metabisulphite and sunset yellow FCF, respectively. Conclusion:

There is a high risk of exposure of neonates to harmful excipients, and

clinicians need to be aware of this during neonatal care.

Keywords: Additives, Harm, Medications, Sodium metabisulphite.

|

|

E xcipients play a major

role in converting medicinal agents to acceptable dosage

forms[1]. Neonates are a vulnerable population and their drug

handling, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic aspects are

different from older children. Neonates may be exposed to risks

and unwanted effects of excipients when they are administered

drug formulations. The reason could be immature physio-logical

functions leading to inadequate metabolism and excretion of such

excipients from body [2-4].

In the 1980s, ten neonatal gasping syndrome

and death were reported in a study as a result of toxicity of

benzyl alcohol (preservative) used in intravenous solutions [5].

Parabens, ethanol and propylene glycol are other examples of

excipients having harmful effects in neonates [1]. Therefore,

this study was conducted to assess types and amount of exposure

to excipients among neonates in neonatal intensive care unit

(NICU).

METHODS

This prospective observational study was

conducted in the NICU of a tertiary care teaching hospital in

Bangalore for duration of 2.5 years (January, 2017 to June,

2019) after approval from institutional human ethics committee.

Valid consent was given by the parents/guardians of included

study subjects who received at least one drug. Neonates dying

within 24 hours of birth were excluded. Demographic details

(gestational age, birthweight, gender, date of birth, post natal

age), length of stay, daily clinical progress of neonates,

information about prescribed medicines for all neonates

(indication, dose, frequency, route of administration, dosage

form and brand names) were recorded. Diagnoses were classified

according to ICD-10 (International statistical classification of

diseases and related health problems, 10th revision, 2016).

Administered drugs were classified according to WHO Anatomical

Therapeutic and Chemical (ATC) classification system.

Lists of excipients and their quantities

present in each prescribed formulation were collected by

referring to package insert leaflets (PIL) of drugs or

contacting the manufacturers. Excipients were categorized into

four groups as per Lass, et al. [1] viz., (a)

known to be harmful to neonates (adverse reactions reported in

neonates); (b) potentially harmful (adverse reactions

reported); (c) no safety data found (no data found in the

literature on human exposure and toxicity); and (d)

description of the excipient in PIL non-specific (description

does not allow a specific literature search).

Statistical analyses: Daily exposure to

excipients (mg/kg/day) were calculated based on available data

on quantity of excipients in formulations, and were compared

with acceptable daily intake (ADI) [6-8] for those which data of

ADI was available.

RESULTS

Of the 790 cases admitted to NICU during the

study period, 41 were excluded as they had received only

phototherapy (no medications), and 3 babies died within 24 hours

of birth. The baseline characteristics of 746 included neonates

are described in Table I. The most frequent

diagnoses were respiratory distress of newborn, neonatal sepsis

and congenital heart disease.

Table I Characteristics of Neonates (N=746)

|

Characteristics |

Value |

|

Male sex |

424 (56.8) |

|

Inborn babies |

576 (77.2) |

|

Gestational age, wk |

|

|

Term ( ³37) |

408 (54.7) |

|

Moderate to late preterm (32 to <37) |

274 (36.7) |

|

Very preterm (28 to <32) |

55 (7.4) |

|

Extremely preterm (<28) |

9 (1.2) |

|

*Length of stay, d |

|

|

Term |

5.7 (0.91) |

|

Moderate to late preterm |

8.4 (0.80) |

|

Very preterm |

19.27 (4.90) |

|

Extremely preterm |

27.33 (4.16) |

|

*Birthweight, g |

2480 (700) |

|

All values in n (%) except *mean (SD). |

The total number of prescribed drugs was

5535, and 77 different drugs were given. Systemic

anti-infectives, blood and blood forming organs, and alimentary

tract and metabolism class were the most commonly prescribed

classes of drugs. Intravenous (49, 63.6%) and oral (18, 23.3%)

were the most common routes of administration.

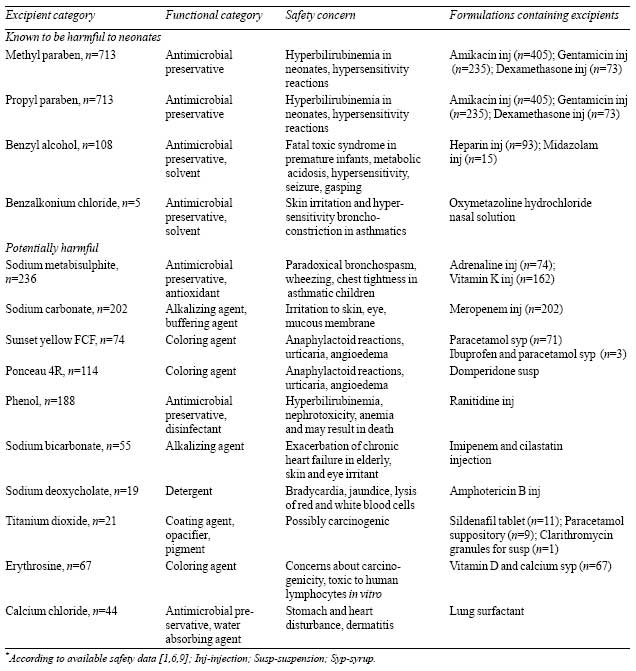

The qualitative and quantitative information

on excipients were available only for 35 and 15 drugs,

respectively. Total of 27 different excipients were identified.

Of all excipients, 4 (14.8%) and 10 (37%) were grouped under

category a and category b, respectively. These excipients were

present in 26% (20/77) of prescribed formulations, details of

which, including safety concerns [1,6,9], are given in

Table III. It was found that the highest proportion of

above mentioned excipient were present in systemic

anti-infectives.

Table II Amount of Exposure to Excipients in Neonates (N=746)*

|

Excipient |

Adult ADI [6-8] |

Daily dose exposure range |

Comparison with adult ADI |

|

Sodium metabisulphite |

0.7 mg/kg/d |

0.09-2.1 mg/kg/d |

‡Higher than ADI

|

|

Benzalkonium chloride |

0.1 mg/kg/d |

0.02-0.09 mg/kg/d |

Within ADI range |

|

Methyl paraben |

10 mg/kg/d |

0.03-1 mg/kg/d |

Within ADI range |

|

Propyl paraben |

10 mg/kg/d |

0.0003-0.09 mg/kg/d |

Within ADI range |

|

#Benzyl alcohol |

5 mg/kg/d |

0.016-1.3 mg/kg/d |

Within ADI range |

|

Phenol |

<50 mg in 10 h period |

0.1-0.8 mg in 12 h |

Within ADI range |

|

Sunset yellow FCF |

2.5 mg/kg/d |

0.3-4.2 mg/kg/d |

^Higher than ADI |

|

*Based on available data on quantity of excipients

present in drugs; ADI: Acceptable daily intake; #should

not be used in neonates; ‡12.3 % of exposures with use

of adrenaline injection; ^12.7 % of exposures with use

of paracetamol syrup. |

Emulsifier 472 C was the only identified

excipient of category c. Remaining excipients (8, 29.6%)

including yellow and red oxides of iron, caramel colour and

flavours were classified under category d. Daily exposure to

excipients of 8 injections (vitamin K, adrenaline, amikacin,

gentamicin, dexamethasone, heparin, midazolam and ranitidine),

oxymetazoline hydrochloride nasal solution and paracetamol syrup

were assessed and compared to ADI (table II).

|

Table III Classification of

Excipients to Which Neonates were Exposed*

|

|

DISCUSSION

This study on qualitative and quantitative

excipient exposure among hospitalized neonates in India found

that 86.9% and 53.8% of neonates were exposed to at least one

excipient known to be harmful or potentially harmful,

respectively. Previous studies conducted in Brazil and Estonia

found that almost all neonates were prescribed drugs containing

at least one harmful excipient [1,3]. We found that harmful and

potentially harmful excipients were present in formulations that

were administered frequently and simultaneously. Hence neonates

could be at greater risk of toxic effects. Similarly, Fister,

et al. [10] reported that 51.6% of added excipients in

formulations were potentially harmful and harmful ones.

Coloring agents (ponceau 4R, sunset yellow

FCF, erythrosine and titanium dioxide) present in oral dosage

forms were included in potentially harmful category. Regulatory

status on colorants in different countries are not similar; in

the European union, medicines containing sunset yellow and

ponceau 4R must carry warning label concerning possible allergic

reactions [6]. In our study, Ponceau 4R was most frequently

observed colorant, though its use is banned in some countries

due to its effect on neurocognitive development and behavior

[2].

The use of category a or b excipients in

intravenous/oral formulations was much lesser in our study than

findings of Lass, et al. [1]. However, in another study

carried out in Spain [11], 32% of intravenous formulations and

62% of oral formulations contained at least one harmful

excipient. These differences can be explained by the

availability of information of excipients present in

formulations in different countries. We found high rates of

exposure (higher than ADI) to sodium metabisulphite and sunset

yellow FCF. Similar findings were reported by Akinmboni, et

al. [12] that 11% of neonates were exposed to a higher

amount of an excipient than the FDA/WHO recommended adult dose.

Daily exposure to phenol (in ranitidine

injection) was within the adult ADI range. However, literatures

show that use of ranitidine in very low birth weight neonates

can increase incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis, mortality

and infection [13]. Safety concern regarding use of ranitidine

was reported to the neonatologist. Daily exposure to benzyl

alcohol did not exceed the adult ADI. However, as per FDA

recommendation and label of the heparin injection, benzyl

alcohol containing formulations should not be used for neonates

and premature infants due to risk of fatal toxic syndrome in

neonates [6,14-16]. Unfortunately, 14.5% of neonates were

exposed to benzyl alcohol containing formulations. For 12.5% of

exposures, alternative preservative free formulation with the

same concentration of heparin sodium injection and similar cost

was available, which were suggested to the neonatologist.

Another study conducted in Netherlands showed that oral liquid

medicines without potentially harmful excipient were available

for 22% of medicines [17].

An important limitation of the present study

was the lack of data on neonatal ADI of excipients due to

barriers to conduct such studies. Another limitation was lack of

information about list of excipients and their quantities

present in each formulation. So, we could not assess the extent

of exposure to all excipients of formulations. However, our

findings with limited available data show that exposure to

harmful excipients is high, and awareness regarding their risks

needs to be raised.

Substitution of those medications with

excipient (harmful) free formulations, at least in high risk

conditions, will avoid unwanted risks. It is also important that

manufacturers disclose detailed qualitative and quantitative

information of excipients of formulations to clinicians and

clinical pharmacists, for risk/benefit assessment of selection

of drugs for neonates.

Ethical clearance: VIPS Human Ethics

Committee; IEC/2016-14 dated December 09, 2016.

Contributors: SN: collected the data,

analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript; NKM: designed,

monitored and supervised the study and approved the final

manuscript; SB: was the neonatologist who co-supervised the

study.

Funding: None; Competing interest:

None stated.

| |

|

What This Study Adds?

•

It is advisable that

excipient exposure be assessed while selecting medicinal

formulations for neonates.

|

REFERENCES

1. Lass J, Naelapää K, Shah U, Käär R,

Varendi H, Turner MA, et al. Hospitalized neonates in

Estonia commonly receive potentially harmful excipients. BMC

Pediatr:2012; 12:136.

2. Whittaker A, Currie AE, Turner MA, Field

DJ, Mulla H, Pandya HC. Toxic additives in medication for

preterm infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed: 2009;94:

F236-40.

3. Souza A Jr, Santos D, Fonseca S, Medeiros

M, Batista L, Turner M, et al. Toxic excipients in

medications for neonates in Brazil. Eur J Pediatr:

2014;173:935-45.

4. Kearns GL, Abdel-Rahman SM, Alander SW,

Blowey DL, Leeder JS, Kauffman RE. Developmental

pharmacology-Drug disposition, action, and therapy in infants

and children. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1157-67.

5. Gershanik J, Boecler B, Ensley H,

McCloskey S, George W. The gasping syndrome and benzyl alcohol

poisoning. N Engl J Med.1982;307:1384-8.

6. Rowe RC, Sheskey PJ, Quinn ME. Handbook of

Pharmaceutical Excipients, 6th ed. Pharmaceutical press; 2009.

7. Commission of the European Communities.

Report from the Commission on Dietary Food Additive Intake in

the European Union. Available from:

https://ec.europa.eu/transparency/regdoc/rep/1/2001/EN/1-2001-542-EN-F1-1.Pdf.Accessed

January 10, 2019.

8. European food safety authority (EFSA).

Reasoned opinion on the dietary risk assessment for proposed

temporary maximum residue levels (MRLs) of

didecyldimethy-lammonium chloride (DDAC) and benzalkonium

chloride (BAC). Available from: https://efsa.onlinelibrary.

wiley. com/doi/epdf/10.2903/j.efsa.2014.3675. Accessed

January 13,2019.

9. European Medicines Agency.Committee for

Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). Reflection Paper: for-mulations

of choice for the paediatric population. Available from:

https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/reflection-paper-formulations-choice-paedi

atric-population_en.pdf. Accessed December 12, 2018.

10. Fister P, Urh S, Karner A, Krzan M,

Paro-Panjan D. The prevalence and pattern of pharmaceutical and

excipient exposure in a neonatal unit in Slovenia. J Matern

Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;28:2053-61.

11. Garcia-Palop B, Movilla Polanco E, Cañete

Ramirez C, Cabañas Poy MJ. Harmful excipients in medicines for

neonates in Spain.Int J Clin Pharm. 2016;38:238-42.

12. Akinmboni TO, Davis NL, Falck AJ, Bearer

CF, Mooney SM. Excipient exposure in very low birth weight

preterm neonates. J Perinatol. 2018;38:169-74.

13. Terrin G, Passariello A, De Curtis M,

Manguso F, Salvia G, Lega L, et al. Ranitidine is

associated with infections, necrotizing enterocolitis, and fatal

outcome in newborns. Pediatrics: 2012;129:e40-5.

14. Committee on Fetus and Newborn, Committee

on Drugs. Benzyl Alcohol: Toxic Agent in Neonatal Units.

Pediatrics:1983;72:356-8.

15. Hiller JL, Benda GI, Rahatzad M, Allen

JR, Culver DH, Carlson CV, et al. Benzyl alcohol

toxicity: Impact on mortality and intraventricular hemorrhage

among very low birth weight infants. Pediatrics: 1986;77:500-6.

16. CDC. Neonatal deaths associated with use

of benzyl alcohol-United States. Available from:

https://www.cdc. gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00001109.htm.

Accessed August 13, 2018.

17. Van Riet-Nales DA, de Jager KE, Schobben

AF, Egberts TC, Rademaker CM. The availability and

age-appropriateness of medicines authorized for children in the

Netherlands. Br J Clin Pharmacol:2011;72:465-73.

|

|

|

|

|