|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2019;56: 749-752 |

|

Improvement in Successful Extubation in

Newborns After a Protocol-driven Approach: A Quality Improvement

Initiative

|

|

Rameshwar Prasad

and Asit Kumar Mishra

From Department of Pediatrics, Tata Main Hospital,

Jamshedpur, Jharkhand, India

Correspondence to: Dr Rameshwar Prasad, Flat no 3,

Crystal Villa, Kadma Jamshedpur 831 005, Jharkhand, India.

Email:

[email protected]

Received: June 22, 2018;

Initial review: December 03, 2018;

Accepted: June 11, 2019.

|

|

Objective: To reduce extubation

failure rate by implementing protocol-driven ventilation and extubation

strategies. Methods: Quality improvement project in a level II

neonatal care unit from April 2017 to January 2018. Ventilation and

extubation protocols implemented from 1 August, 2017. 18 ventilated

newborns in the pre-protocol period, 16 in Plan-do-check-act (PDCA)

cycle I and 17 in PDCA cycle II. Primary outcome was

extubation failure within the first 72 h of extubation. Results:

Extubation failure rate reduced from 41.7% (pre-protocol period) to

23.8% (PDCA 1 and 2, OR 0.44, 95% CI 0.12 to 1.59, P = 0.21).

Median time to first extubation attempt significantly decreased (71.5 h

to 38 h, P=0.046). Conclusions: A protocolized approach

through quality improvement initiative demonstrated a sustained

improvement in successful extubation with a significant reduction in the

median time to first extubation attempt in ventilated newborns.

Keywords: Extubation failure, Neonate, Quality

improvement, Ventilation.

|

|

E

arly successful extubation of ventilated newborns

is an important way to reduce ventilator-induced lung injury, sepsis and

length of stay. Evidence-based strategies improve successful extubation

rate [1,2]. Nonetheless, the inconsistent practices and arbitrary

approach to ventilation and extubation result in repeated extubation

failures and consequential reintubation [3,4]. An average of 25%

ventilated newborns fail extubation [5,6]. Extremely preterm newborns

have a much higher risk of failed extubation [7]. The evidence of

protocol-driven management approach in reducing the duration of

mechanical ventilation and weaning time is limited in newborns [8]. This

study was designed to assess the impact of quality improvement on

extubation failure in neonates.

Methods

The study was conducted in a level II neonatal care

unit in an industrial hospital in India between 1

April, 2017 and 31

January, 2018. The study had 3 periods – Baseline (1

April, 2017 – 30 June, 2017), Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) cycle I (1

August, 2017 – 31

October, 2017) and PDCA cycle II (1

November, 2017 – 31

January, 2018). Our primary outcome was extubation

failure which was defined as reintubation within 72 hours of extubation

irrespective of the cause [6]. Reintubation was defined as intubation

occurring after 72 hours of extubation and was excluded from extubation

failure. During the baseline period, patient data were collected by

reviewing patients’ charts and electronic database. We constituted a

team comprising a consultant-in-charge of the neonatal unit,

specialists, a neonatologist and two senior nursing staff. In a

brainstorming session, the probable causes of extubation failure were

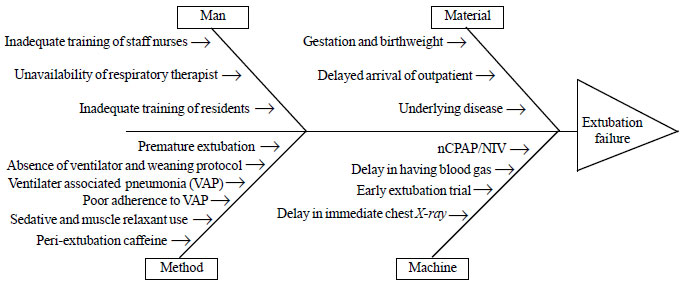

identified and put into a fish-bone diagram (Fig. 1). Most

of the modifiable root causes of extubation failure belonged to man and

method groups. Further, why-why analysis led us to the two main problems

of lack of standardized ventilation and extubation strategies.

|

|

Fig. 1 Cause and effect diagram.

|

We addressed the above two problems by drafting

ventilation and extubation strategies by searching the literature for

evidence-based practices. We prepared a checklist for extubation

readiness. Printed copies of ventilator strategy, ventilator-associated

pneumonia (VAP) prevention bundle and checklist for extubation readiness

were displayed at the bedside. Training was given to residents,

pediatricians and staff nurses twice a month about the protocol and

records maintained. The consultant-in-charge of the neonatal unit

crosschecked the extubation checklists before taking a decision to

extubate a newborn. Post-extubation adrenaline nebuli-zation was given

regularly although its evidence is lacking in newborns. We did not

include peri-extubation dexamethasone in the protocol due to concerns

over both short and long term complications.

The protocols were implemented from 1

August, 2017. Ethical approval was not sought as

this was a quality improvement initiative. Our primary objective was to

reduce extubation failure rate by 25% from baseline. Secondary outcomes

to assess the impact of intervention were: time of first extubation

attempt, multiple extubation failures (defines as two or more extubation

failures in a newborn during hospital stay) and duration of mechanical

ventilation. During the first PDCA cycle, patient data for all baseline

and outcome variables were collected.

During PDCA cycle II, we uploaded the protocol in the

hospital’s digital document control system. Nursing staff and residents

were given training monthly and ventilator and weaning strategies were

discussed with them during daily rounds.

The study included all consecutively ventilated

newborns during the study period. Newborns who died, discharged

against medical advice (DAMA) or those referred to higher center before

attempting first extubation were excluded from analysis.

Statistical analyses: SPSS 15 was used to analyze

data. Data were examined for normality by Kolmogorov-Smirnov and

Shapiro-Wilk tests. We used the chi-square test and Fischer’s exact test

for categorical variables. Independent t-test and Mann Whitney U test

were used for continuous variables, as appropriate. A P value of

<0.05 was considered statistically significant and all tests were

2-tailed. The data were analyzed on an intention-to-treat basis.

Results

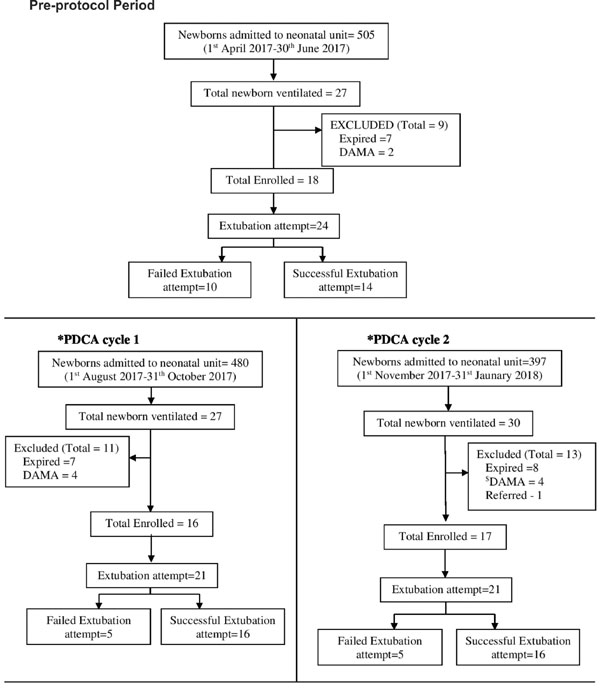

Study flow is depicted in Fig. 2. The

demographic characteristics were similar in all three groups. In

baseline period, PDCA-1 and PDCA-2, mean (SD) birth weight was 2168

(1008), 2176 (861.4), and 2226 (651) g, and mean (SD) gestational age

was 34.6 (3.4), 34.2 (4.6) and 35.0 (3.7) wk, respectively. In the three

groups, males were 67%, 75% and 76% and inborn newborns were 61%, 42%

and 53%, respectively. Table I provide the details of

outcomes in the three groups. There was a significant reduction in time

to first extubation attempt.

|

|

Fig. 2 Participant recruitment

flow diagram.

|

TABLE I Clinical Outcomes in Neonataes Before and After a Quality-improvement Intervention (N=17)

|

Outcome |

Pre-protocol period (n=18) |

PDCA-1 (n=16) |

PDCA-2 (n=17) |

|

Extubation failure rate* |

10/24 (41.7%) |

5/21 (23.8%) |

5/21(23.8%) |

|

Extubation failure ≥2#

n/N (%) |

4/18 (22.2%) |

1/16 (6%) |

0/17 |

|

Time (h) of first extubation attempt, median (IQR) |

71.5 (46.5-75) |

51 (16.6-92.4) |

38$ (21.5-83) |

|

Duration (h) of mechanical ventilation, median (IQR) |

73.5 (70.5-139.3) |

68.5 (18.8-96.3) |

49 (22.0-112.5) |

|

*PDCA: plan-do-check-act cycle; *Number of re-intubations

within 72 h of extubation ÷ total number of extubation attempts

(%); #Number of newborns needed

≥2 reintubations within 72 h of extubation÷ total number

of newborns in that period (%); $P= 0.046

(pre-protocol vs PDCA-2). |

Compliance to caffeine use, pre-extubation chest X-ray,

target minimal ventilator settings, withholding enteral feed, inotropes

and sedation according to extubation checklist was 100% in both

post-protocol periods 1 and 2. Compliance to pre-extubation blood gas

analysis was 33.3%. All newborns were ventilated on either

Synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation – pressure support or

Assist control mode.

Discussion

In the present study, quality improvement PDCA cycles

resulted in significant reduction in extubation failure rate. It also

resulted in time to first extubation attempt.

The major constraint of this study is small sample

size from a single center that limits generalizability and precludes

subgroup analysis. The study group is heterogeneous in gestational age,

birth weight and morbidities that can introduce selection bias.

Prolonged mechanical ventilation in very preterm newborns could

potentially confound the results. Out-born newborns coming late to our

hospital preclude early surfactant therapy and/or early ventilator

support. Our study did not measure other important outcomes e.g.

retinopathy of prematurity, bronchopulmonary dysplasia and neuro-developmental

outcomes.

Extubation failure is multifactorial and a single

intervention may not bring down its incidence. The extubation failure

rate varies widely among centers depending on the characteristics of

patients and the mode of support used after extubation. The definition

of extubation failure varies widely in literature from 24 hours to 7

days after extubation [6,9]. Two randomized controlled trials comprising

a small subgroup of term newborns evaluating weaning protocol were

inconclusive [8,10,11]. Hermato, et al. [12] demonstrated a

significant reduction in extubation failure rate, the median age of

first extubation attempt and the median duration of mechanical

ventilation in newborns (birth weight

³1250 g) after

implementing respiratory therapist-driven ventilation protocol in a

retrospective study. These were similar to results of the present study.

Our findings underscore the importance of using

quality improvement methodology [13,14] in settings where failed

extubation is a common troublesome phenomenon. The ventilation and

extubation protocols can be further updated according to available

resources at the local level as well as the current best scientific

knowledge. Studies are needed to study the impact of this approach on

other morbidities.

Acknowledgements: Dr Sudhir Mishra, Head,

Department of Pediatrics, Tata Main Hospital for his valuable inputs in

revising the manuscript. Air Marshal (Dr) Rajan Chaudhry, AVSM, VSM (Retd.),

GM (Medical Services), Tata Main Hospital, for providing permission

to submit the manuscript for publication. Contributors:

RP: planning, collection and analyses of data, literature review and

preparation of final manuscript; AKM: concept and design of the study,

review and revision of manuscript, final approval of manuscript. Both

authors approved the final version of manuscript, and are accountable

for all aspects related to the study.

Funding: None; Competing Interest: None

stated.

|

What This Study Adds?

•

A ventilation and extubation strategy, implemented using the

quality PDCA methodology, has the potential to reduce extubation

failure and time to first extubation attempt in ventilated

newborns.

|

References

1. Lemyre B, Davis Pg, De Paoli Ag, Kirpalani H.

Nasal intermittent positive pressure ventilation (nippv) versus nasal

continuous positive airway pressure (ncpap) for preterm neonates after

extubation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;2:CD003212,

2. Ferguson KN, Roberts CT, Manley BJ, Davis PG.

Interventions to improve rates of successful extubation in preterm

infants: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr.

2017;171:165-74.

3. Al-Mandari H, Shalish W, Dempsey E, Keszler M,

Davis PG, Sant’anna G. International survey on periextubation practices

in extremely preterm infants. Arch Dis Child - Fetal Neonatal Ed.

2015;100:F428.

4. Shalish W, Anna GMS. The use of mechanical

ventilation protocols in canadian neonatal intensive care units.

Paediatr Child Health. 2015;20:e13-9.

5. Hiremath GM, Mukhopadhyay K, Narang A. Clinical

risk factors associated with extubation failure in ventilated neonates.

Indian Pediatr. 2009;46:887-90.

6. Giaccone A, Jensen E, Davis P, Schmidt B.

Definitions of extubation success in very premature infants: A

systematic review. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2014;99:f124-7.

7. Hermeto F, Martins BMR, Ramos JRM, Bhering CA,

Sant’anna GM. Incidence and main risk factors associated with extubation

failure in newborns with birth weight < 1,250 g. J Pediatr (Rio J).

2009;85:397-402.

8. Wielenga JM, van den Hoogen A, van Zanten HA,

Helder O, Bol B, Blackwood B. Protocolized versus non protocolized

weaning for reducing the duration of invasive mechanical ventilation in

newborn infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;3:cd011106.

9. Wang S-H, Liou J-Y, Chen C-Y, Chou H-C, Hsieh W-S,

Tsao P-N. Risk factors for extubation failure in extremely low birth

weight infants. Pediatr Neonatol. 2017;58: 145-50.

10. Schultz TR, Lin RJ, Watzman HM, Durning SM, Hales

R, Woodson A, et al. Weaning children from mechanical

ventilation: A prospective randomized trial of protocol-directed versus

physician-directed weaning. Respir Care. 2001;46: 772-82.

11. G Randolph A, Wypij D, Venkataraman S, H Hanson

J, Gedeit R, L Meert K, et al. Effect of mechanical ventilator

weaning protocols on respiratory outcomes in infants and children: A

randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002; 288:2561-8.

12. Hermeto F, Bottino MN, Vaillancourt K, Sant’anna

GM. Implementation of a respiratory therapist-driven protocol for

neonatal ventilation: Impact on the premature population. Pediatrics.

2009;123:e907-16.

13. Chawla D, Darlow BA. Development of quality

measures in perinatal care – Priorities for developing countries. Indian

Pediatr. 2018;9:797-802.

14. Mehta R, Sharma KA. Use of learning platforms for quality

improvement. Indian Pediatr. 2018;9:803-8.

|

|

|

|

|