|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2019;56: 745-748 |

|

Effect of a Formative Objective Structured

Clinical Examination on the Clinical Performance of

Undergraduate Medical Students in a Summative Examination: A

Randomized Controlled Trial

|

|

Nazdar Ezzaddin Alkhateeb 1,

Ali Al-Dabbagh2,

Mohammed Ibrahim3

and Namir Ghanim Al-Tawil4

From Departments of 1Pediatrics, 2Surgery,

4Community Medicine, College of Medicine, Hawler Medicine

University, Erbil, Kurdistan region, Iraq; and 3Clinical

Training, Queensland Health Service, Australia.

Correspondence to: Dr Nazdar Ezzaddin Alkhateeb,

Department of Pediatrics, College of Medicine, Hawler Medical

University, Erbil, Kurdistan region, Iraq.

Email:

[email protected]

Received: February 11, 2019;

Initial review: April 29, 2019;

Accepted: July 13, 2019.

|

|

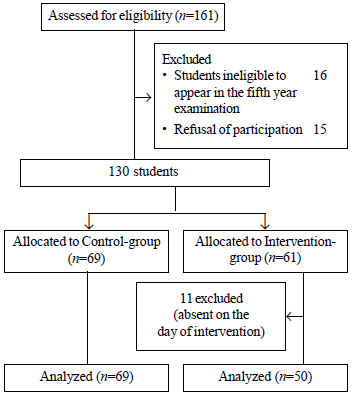

Objective: To study the effect of

formative Objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) on the

undergraduate medical students’ performance in a subsequent

summative-OSCE assessment. Methods: In a randomized single-blind

trial, 130 fifth year medical students at Raparin hospital, Erbil were

assigned to intervention (n=61) and control group (n=69).

Formative-OSCE was performed for the intervention group in pediatric

module with feedback on their performance versus standard

pediatric module for the control group. Students’ clinical performance

was assessed by a summative-OSCE. Multiple regression was used to

predict the summative-OSCE score depending on the participation in

formative-OSCE along with the other factors. Results: Eleven

students were excluded because of early drop-out, leaving 119 students

for analysis. The summative-OSCE mean score (out of a total score of

100) in intervention group 64.6 (10.91) was significantly lower as

compared to the control group 69.2 (10.45). Conclusion: Single

formative-OSCE does not necessarily lead to better performance in

subsequent summative-OSCE.

Keywords: Assessment, Clinical

competence, Educational measurement, Medical Eduation.

Trial Registration: Clinical trial.gov/NCT 035

99232.

|

|

A

ssessment is the cornerstone of any educational

project. It gives evidence about the success in the achievement of

specific learning outcomes [1,2]. Depending on the time and the intent,

assessment can serve three functions: diagnostic, a function for

prevention of learning difficulties; formative, a function for

regulating learning with delivery of feedback; and summative, a function

for certificate or social recognition [3].

As the assessment role shifts from a pure assessment

of learning to assessment for learning, there is an incentive to

determine how and when assessment of different forms have educational

value [4]. Unlike other

professional training culture, true feedback culture is not cultivated

in medical education. Therefore, a formative assessment must be at the

core of student training, not just included to fulfill accreditation

requirement [5].

In a performance-based assessment, the Objective

Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) has gained importance because of

its reliability [2], and could be used in a summative or formative way

to measure clinical competence [6-8]. There are several medical schools

where formative assessments are established and carried out on regular

basis; unfortunately, it is not very frequent in the Mediterranean

countries [1]. Meanwhile,

undergraduate medical education in Iraq is going through a transitional

period and has started the process of changing its curriculum to

competency-based medical education – formative assessment of students’

performance is a requirement in this process.

Though previous studies suggest that formative-OSCE

contributes positively to final summative examination performance [9],

these were based on the students’ perception [10,11]. Therefore, this

study aims to look for evidence to evaluate if a single formative-OSCE

has an impact on student’s clinical performance in summative

competency-based assessment.

Methods

A single-blind randomized controlled trial was

conducted on fifth year medical students who attended a seven-week

pediatric module at Raparin pediatric hospital, Erbil between September

2016 and May 2017. Our medical college provides a 6-year MBChB program.

Students were divided randomly by the registration office into four

groups: A, B, C and D with around 40 students per group, which attended

the pediatric module at a specific time of the year. At the end of

pediatric module, students’ clinical competencies were assessed by a

summative-OSCE. Students’ performance data (fourth year grade point

average (GPA)) was obtained from student records. A student’s GPA is a

standard way of measuring academic achievement at the end of academic

year. Each course is given a certain number of credits depending on the

content of the course. It is calculated by the

S (scores obtained by

the students in each course x the credit unit of that course) /

S credit units.

The trial was approved by our institutional ethics

committee. All students were suggested to participate in the study and

provided written consent. Student groups were randomized with a computer

program (Microsoft Excel 2010) into two groups: intervention group and

control group. Students were not randomized as individuals from each of

the groups to avoid knowledge contamination between the students of the

same group. We concealed the groups’ allocation until the start of the

intervention (Fig. 1).

|

|

Fig. 1 Study flow chart.

|

A formative-OSCE was performed for the intervention

group at the beginning of the pediatric module to assess the

competencies they gained from previous modules. The author explained the

purpose of formative-OSCE as a learning experience in the study group.

Failing the formative-OSCE had no adverse effect on the final summative

scores and the participation was voluntary. In comparison, the

participants in control group were attending the standard pediatric

module.

The formative-OSCE design involved a blueprint

development that served as a guideline for the development and

face-validation of the eight stations, which were both interactive and

static. The interactive stations included history taking, examination,

communication and procedural skills while non-interactive stations

included data interpretation, management and a video-station.

The formative-OSCE examiners consisted of two

teaching staff and 11 postgraduate pediatric board trainees, who were

trained by the investigators. At the time of result declaration,

students received feedback on their performance in the formative-OSCE on

a one-to-one basis. Feedback was given by the author as narrative

feedback as well as scores.

The examiners in the summative-OSCE were blinded to

the group assignment and the two-teaching staff who took part in the

intervention, did not participate in the summative exam. The allocation

sequence was generated by a person not involved in the data analysis.

The main outcome was the students’ performance in summative-OSCE. This

was measured by students’ summative-OSCE scores with the passing mark of

a total of at least 50 from all stations.

Statistical Package for Social Sciences (IBM SPSS

version 21) was used for data analysis. Sample size was calculated based

on previous studies [12] by statistical software, the power was set at

90% and a=0.01.

Accordingly, the estimated sample size was 27 for each group.

Considering the non-response rate probability, the authors decided to

include all the students. Students’ t-test used for two independent

samples and paired t-test to compare between pre- and post-module OSCE

scores of the same group. Multiple regression was used to analyze effect

of different factors on summative-OSCE and McNemar test to compare

proportions of the same sample (formative and summative-OSCE success

rate of the intervention group). A P-value of less than 0.05 was

considered significant.

Results

Of the 161 students who attended the seven weeks

pediatric module and screened, 130 were eligible for enrolment (Fig.

1). We excluded 11 students of the intervention group from the

initial analysis as they did not participate in the formative-OSCE due

to their absence on the day of formative-OSCE. There were no significant

differences in the baseline characteristics of the two groups except for

the place of residence (Table I).

TABLE I Baseline Characteristics of Fifth Year Medical Undergraduates Enrolled in the Study (N=119)

|

Factors |

Student-group |

|

Control group

|

Intervention group |

|

(n=69) |

(n=50)

|

|

Place of residence* |

|

Local |

43 (62.3) |

49 (98) |

|

Dormitories |

26 (37.6) |

1(2) |

|

English-based secondary school# |

|

No |

60 (86.9) |

42 (84) |

|

Yes |

9 (13.04) |

8 (16) |

|

Female gender |

38 (55.07) |

27 (54) |

|

Previous year GPA |

Average-grade |

Average-grade |

|

Mean (SD) |

61.48 (6.3) |

66.37 (6.7) |

|

*P<0.001; # P=0.6; $P = 0.9. |

The intervention group’s summative-OSCE mean (SD)

score 64.6 (10.9) was significantly higher than their formative-OSCE

mean (SD) score 53.5 (8.3) (P<0.001). A comparison of both

intervention and control group did not show a statistically significant

difference in pass rate in the summative-OSCE [48/50 (96%) and 67/69

(97%), respectively]. Interestingly, the mean (SD) summative-OSCE score

of the control group 69.2 (10.45) was higher than that of the

intervention group 64.61(10.91) (P=0.02).

Multiple regression analysis revealed that the

summative-OSCE scores were positively correlated with the previous year

grade point average, and negatively correlated with participation in the

formative-OSCE (P<0.001) (Table II).

TABLE II Output for a Multiple-regression Model Where the Dependent Variable is Scores of Summative-OSCE (N=119).

|

Model |

B |

P value |

95.0% Confidence-Interval for B

|

|

|

|

(Lower-Bound,

|

|

|

|

Upper-Bound) |

|

(Constant) |

10.226

|

0.201 |

(-5.542, 25.994) |

|

Previous year GPA |

0.951

|

<0.001 |

(0.703, 1.199) |

|

English-based secondary school |

-0.613

|

0.798 |

(-5.340, 4.114) |

|

Male gender |

0.171

|

0.917 |

(-3.068, 3.410) |

|

Place of residence (dorm) |

1.374

|

0.532 |

(-2.964, 5.713) |

|

Participation in formative-OSCE |

-8.754

|

<0.001 |

(-12.491, -5.018) |

Discussion

The formative-OSCE introduction did not result in a

considerable change in the overall summative-OSCE pass rate in the

intervention group compared with the control group, similar to results

obtained by Chisnall, et al. [6], but it improved the students

mean score in the intervention group if compared with their

formative-OSCE mean.

This finding supports the work of other studies in

this area linking medical students review of formative-OSCE scores and

their performance in summative-OSCE [13]. But it is contradictory to

other researches that appreciate the role of formative assessment in

improving the overall performance in OSCE [14,15].

One criticism of much of the literature on formative

assessment effectiveness is that it does not depend merely on its

availability; it rather relies upon the quality and communication tools

of the assessment feedback [16]. In this study, feedback on students’

performance in formative-OSCE was provided by the authors in form of

comments and numerical scores. Even though it is difficult to disagree

with the efficiency of numerical scores for summative purposes, its use

for formative purposes that guide progress in learning has long been

argued [17]. Numerical scores and letter grades would tend to direct

students’ concentration to the self and away from the task, thus leading

to a negative impact on performance [17,18].

According to cognitive evaluation theory, even

positive feedback that is useful for students can be weakened by

negative motivational effects as a result of giving grades or comparing

the students to a norm [19].

Feedback could be immediate or delayed according to

its timing. When it is planned to facilitate lower-order learning

outcomes, for example, the recall of facts, prompt feedback works best.

However, when higher-order learning outcomes are a concern and

necessitate the transfer of what has been learned to a new situation,

delayed feedback probably works better [20]. In this study, feedback was

given when the results were released (delayed); although, it is

suggested that students prefer immediate feedback [20].

Another factor is that having four summative-OSCEs

for the four groups of the 5th year might have contributed to possible

difference in summative examination difficulty; although, all the OSCEs

had the same blueprint. This was noticed when comparison was made

between the mean (SD) summative-OSCE scores gained by the intervention

group 64.6 (10.9) with what was gained by the excluded students from the

intervention group 53.4 (15) (P<0.001), even though there was no

significant difference in their GPA of the previous year. Whilst this

was a potential limitation, it had the benefit of excluding prior

knowledge influence on success in the summative-OSCEs.

Moreover repeated administration of OSCE by teaching

hospitals improves the performance of students on the successive

summative-OSCE [15]. However, in our study formative-OSCE was carried

out once.

To conclude, students who faced a single

formative-OSCE obtained less summative-OSCE scores than their

peers in control group.

Contributors: MI,NA,AA: study design and concept;

NG was the trial coordinator and participated in data analysis and

interpretation. NA: data collection, data entry and wrote the draft of

manuscript. All authors critically reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Funding: Hawler Medical University. No

contribution to data design, collection, analysis or interpretation was

made by the funding resource. Competing interests: None stated.

Ethical clearance: The study was approved

by Ethics Committee of the College of Medicine of Hawler Medical

University (document no.16, 23/4/2016)

|

What This Study Adds?

• Participation in a single formative-OSCE did not improve

the students’ performance in a subsequent summative-OSCE.

|

References

1. Carrillo-de-la-Peña MT, Baillès E, Caseras X,

Martínez À, Ortet G, Pérez J. Formative assessment and academic

achievement in pre-graduate students of health sciences. Adv Heal Sci

Educ. 2009;14:61-7.

2. Siddiqui ZS. Framework for an effective

assessment: From rocky roads to silk route. Pakistan J Med Sci.

2017;33:505-9.

3. Tridane M, Belaaouad S, Benmokhtar S, Gourja B,

Radid M. The impact of formative assessment on the learning process and

the unreliability of the mark for the summative evaluation. Procedia

-Social Behav Sci. 2015;197:680-5.

4. Pugh D, Desjardins I, Eva K. How do formative

objective structured clinical examinations drive learning? Analysis of

residents’ perceptions. Med Teach. 2018;40:45-52.

5. Konopasek L, Norcini J, Krupat E. Focusing on the

formative: Building an assessment system aimed at student growth and

development. Acad Med. 2016;91:1492-7.

6. Chisnall B, Vince T, Hall S, Tribe R. Evaluation

of outcomes of a formative objective structured clinical examination for

second-year UK medical students. Int J Med Educ. 2015;6:76-83.

7. Sobh AH, Austin Z, Izham MIM, Diab MI, Wilby KJ.

Application of a systematic approach to evaluating psychometric

properties of a cumulative exit-from-degree objective structured

clinical examination (OSCE). Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2017;9:1091-8.

8. Gupta P, Dewan P, Singh T. Objective structured

clinical examination (OSCE) revisited. Indian Pediatr. 2010;47:911-20.

9. Townsend AH, Mcllvenny S, Miller CJ, Dunn E V. The

use of an objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) for formative

and summative assessment in a general practice clinical attachment and

its relationship to final medical school examination performance. Med

Educ. 2001;35:841-6.

10. Furmedge DS, Smith L-J, Sturrock A. Developing

doctors: What are the attitudes and perceptions of year 1 and 2 medical

students towards a new integrated formative objective structured

clinical examination? BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:32.

11. Farahat E, Javaherian-Dysinger H, Rice G,

Schneider L, Daher N, Heine N. Exploring students’ perceptions of the

educational value of formative objective structured clinical examination

(OSCE) in a nutrition program. J Allied Health. 2016;45:20-6.

12. Jain V, Agrawal V, Biswas S. Formative assessment

as an educational tool. J Ayub Med C Abbottabad. 2012;24:68-70.

13. Bernard AW, Ceccolini G, Feinn R, Rockfeld J,

Rosenberg I, Thomas L, et al. Medical students review of

formative OSCE scores, checklists, and videos improves with

student-faculty debriefing meetings. Med Educ Online. 2017;22:1324718

14. Gums TH, Kleppinger EL, Urick BY. Outcomes of

individualized formative assessments in a pharmacy skills laboratory. Am

J Pharm Educ. 2014;78:166.

15. Lien H-H, Hsu S-F, Chen S-C, Yeh J-H. Can

teaching hospitals use serial formative OSCEs to improve student

performance? BMC Res Notes. 2016;9:464.

16. Radford BW. The effect of formative assessments

on teaching and learning [Master]. Brigham Young University. 2010.

Available from: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/2086.

Accessed January 10, 2019.

17. Lipnevich AA, Smith JK. Response to assessment

feedback: The effects of grades, praise, and source of information. ETS

Research Report Series. 2008;1:i-57.

18. Kluger AN, Denisi A. The effects of feedback

interventions on performance: A historical review, a meta-analysis, and

a preliminary feedback intervention theory. Psychol Bull. 1996;9:254-84.

19. Butler R. Enhancing and undermining intrinsic

motivation: The effects of task involving and ego involving evaluation

on interest and performance. Br J Educ Psychol. 1988;58:1-14.

20. Van der Kleij F. Computer-based feedback in

formative assessment. University of Twente 2013. Available from:

https://www.researchgate.net/profile/ Fabienne_ Van_Der_ Kleij/publication/304628867_Computer-based_feedback_

in_formative_assessment/links/57759dbf08aead 7ba0700138/ Computer-

based-feedback-in-formative-assessment.pdf. Accessed January 10,

2019.

|

|

|

|

|