|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2018;55:818-823 |

|

Quality Improvement

Collaborative for Preterm Infants in Healthcare Facilities

|

|

Srinivas Murki 1,

Sai Kiran1,

Praveen Kumar2,

Deepak Chawla3

and Anu Thukral4

From 1Department of Neonatology,

Fernandez Hospital, Hyderabad; 2Division of

Neonatology, Department of Pediatrics, PGIMER, Chandigarh; 3Department

of Pediatrics, GMH, Chandigarh; 4Department of

Pediatrics, AIIMS, New Delhi; India.

Correspondence to: Dr Srinivas Murki,

Chief Neonatology, Fernandez Hospital, Hyderguda, Hyderabad 500 035,

India. [email protected]

|

Across all healthcare settings, it is important not only to provide safe

and effective healthcare, but also to ensure that it is timely,

patient-centered, efficient and equitable. There is a wide variability

in neonatal and perinatal outcomes in India and other developing

countries, with certain units demonstrating clinical outcomes that match

the developed world, while others showing higher than expected mortality

and morbidity. Collaborative quality improvement initiatives offer a

pragmatic way to improve performance of healthcare delivery within and

between neonatal units. Variations in application of evidence-based

healthcare process and dependent health outcomes can be identified and

targeted for improvement in quality improvement cycles. We herein

describe the concept of Collaborative quality improvement, and the

success stories of the best-known Collaborative quality improvement

initiatives across the world. We also highlight the process and progress

of creating Collaborative quality improvement in our country.

Keywords: Evidence-based medicine, Neonatal intensive care

unit, Outcome, PDSA cycle.

|

|

Quality improvement (QI) in healthcare is "the

combined and unceasing effort of everyone – healthcare professionals,

patients and their families, researchers, payers, planners and educators

– to make the changes that will lead to better patient outcomes

(health), better system performance (care) and better professional

development (learning)" [1]. At the core of this QI is orienting

healthcare towards patient needs or meeting their unmet needs. In the

neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), patient would include both the

infant and his/her parents.

Evidence-based medicine (EBM) is all about promoting

‘practices that work, while eliminating those that are ineffective or

harmful’ [2]. There is always this challenge of implementing what we

know from research to what we do in clinical practice [3]. An important

step in the practice of EBM is to evaluate one’s own performance. This

is where quality improvement provides a framework to the clinicians to

provide best possible care for their patients. Taking cues from other

sectors like aviation and nuclear industry, high reliability and safety

culture concepts are now being applied to the NICU environment also. But

the outcomes measured should not be simply life or death but rather what

the family and infant experience over long-term because of the time

spent in the NICU. Considerations of the lifetime outcomes have shown to

improve care for patients and are the most important measures to collect

[4].

With rapid advancements in neonatal care and

interventions like antenatal steroids, non-invasive respiratory support

and surfactant, survival and morbidities of preterm infants have

improved significantly [5-7]. In both developed and developing

countries, it is important not only to provide safe and effective health

care, but also care which is timely, patient-centered, efficient and

equitable. Each of these six dimensions of quality defined by the

Institute of Medicine in its landmark report can be measured and

prioritized as outcomes to be improved using the QI framework [8]. There

is often wide variability between healthcare facilities for all these

outcomes. Some units achieve outcomes that can be benchmarked, while

others may still be at the bottom of the ladder. Some of the variation

can be attributed to the gap between the recommended and available

infrastructure, monetary resources and personnel, which can be improved

by forming a network of secondary- and tertiary-care neonatal units so

that they can learn from each other on how to improve outcomes with more

effective utilization of available resources [9].

Collaborative QI project involves a group of

professionals from a single or multiple organization who get together to

learn from one another, support and motivate each other in a structured

approach with the intent of improving quality of health services. The

underlying concept is that teams learn faster and are more effective in

implementing and spreading improvement ideas and assessing their own

progress when collaborating and benchmarking with each other.

Collaborative initiatives provide an unique opportunity to look into

various clinical practices, outcomes and healthcare costs across

different participating units, which are operating in similar

demographic and economic conditions. Benchmarking these variations in

clinical practices and outcomes is a powerful motivator for

participating teams to improve many outcomes, as it represents what has

been achieved locally by one’s peers [10].

Collaborative QI methodology was started in North

America in the late 1980s (New England Cardiovascular Disease Study

Group, 1986 and Vermont Oxford Network, 1988) with the approach becoming

more popular as the Breakthrough Series by the Institute for Healthcare

Improvement (IHI) in 1995. Neonatal collaborative QI (Web

Table I) [11-18] projects have ranged from collaborative

working to improve the administration of antenatal steroids to eligible

mothers to compliance with transfusion guidelines [19, 20].

Collaborative Learning

The core concepts of a quality improvement

collaborative include (Web Fig. 1) [21, 22]:

• An improvement collaborative is a shared

learning activity that brings a large number of teams from different

sites to work together to gain rapid achievements in processes,

quality and efficiency in a specific area of care (e.g.,

improve breastfeeding rates, reduce Hospital Acquired Infections)

during a defined time period.

• Essential components of any collaborative QI

are [23]: Identifying specific topic or agenda; Stakeholders or

participants include multi-disciplinary teams from different

centers; Clinical and QI experts to support participant teams; Model

for improvement: Plan and test changes; and Series of structured

learning activities over a pre-defined time period.

• At the outset of starting a collaborative QI is

the identification of a common agenda, where good evidence exists on

best practices and has a potential to improve patient-and

system-outcomes. Well defined agenda ensure participating groups

understand their own processes, outcomes and try to ensure closure

of gap between existing and best practices.

• Organizational structure of Collaborative QI

usually has two wings namely data and quality improvement.

Administration is run by an executive committee that develops and

prioritizes strategic plan. Subcommittee on collaborative quality

improvement analyze data and address priority areas of quality

improvement. Person in charge of administrative, data and quality

improvement oversee day-to-day operations [24].

• Developing implementation packages in QI for

individual units includes creating toolkits, webcasts, workshops and

academic presentations on identified areas of quality improvement

and disseminating the knowledge amongst the individual unit stake

holders after identifying a local champion.

• Clinical practices that are evidence based,

practices in places that are good or best and adaptations that lead

to improved care are shared among the participating centers. These

practices and processes form the implementation packages of a

collaborative QI.

• Participation is voluntary and include

multidisciplinary team of doctors, nursing staff and non-clinical

members from different organization. Usually each team has 2-8

members.

• The participating sites work out and test ways

to put in practice the concepts included in the implementation

package and work to overcome barriers to make them work in their

local settings.

• Participating teams collect a set of core

indicators that define the common outcome indicators and shared

process indicators. The process indicators guide the quality of the

care processes the teams are trying to improve and the achievement

of desired health outcomes.

• Participant teams are guided and supported by

clinical and QI experts who also act as facilitators and provide

technical ideas on clinical and quality improvement strategies.

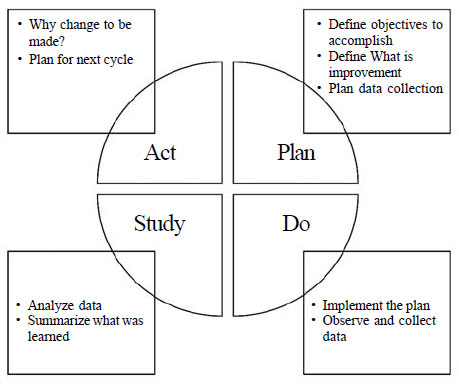

• Teams test changes by applying an improvement

or change model. In any improvement model an intervention is

introduced, and one or more indicators are monitored and measured to

see the effect of the intervention on the desired outcome. Many

improvement models have been implemented using the Model for

Improvement advocated by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement

(IHI) (Fig. 1). Most commonly, practice changes in

NICUs are tested using the Rapid Cycle Model, which involves a

series of Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles [25]. In each cycle, a

small change is planned and tested, the outcomes of the process are

monitored and evaluated, and then further changes are made.

• An intervention that is successful in improving

the process is adopted and if the intervention leads to failure it

is either adapted or abandoned. The change ideas are shared among

the participating centers on a regular basis leading to a faster QI

process, decreasing wastage in systems and saving cost.

• Shared learning is the most distinct

differentiating feature of improvement collaborative from a

traditional QI method. Multiple teams try improvements in same topic

area. The teams test and implement process redesigns and changes and

share their experiences in doing so. This facilitates shared

learning of test changes that are both successful and unsuccessful.

Frequent monitoring of process and outcome indicators and sharing of

test changes help to spur the pace of improvement and creates a

friendly competition among the participating teams. The network of

shared learning results in rapid development and testing of

innovations to solve problems, rapid dissemination of effective

changes, and rapid development of effective models of care,

enhancing the original implementation package of evidence-based

standards with operational learning. Shared learning may also

involve communication of results by coaches who visit multiple

teams, use of a Web site where data and experiences are posted,

telephone calls, smaller meetings of representatives from all QI

teams together [21].

• Typically, collaborative QI projects run for

9-18 months; launched with an initial shared learning session of 2

days, where all participants teach and learn. This session includes

sharing the aim, defining changes, measures and outcomes. Also, the

participants develop action plans. In addition, monthly conference

or video call is done to review data reports on strategies, changes

and learning. Feedback and coaching from reports is done once or

twice per month for all. Two to three learning sessions are done

separated over duration of few months, wherein participating units

freely exchange ideas, share strategies employed to overcome

obstacles and create an environment of tactic competition. Three to

six months after the conclusion of collaborative QI project, a

shared learning session is conducted to sustain the improvements

gained [24].

|

|

Fig. 1 PDSA model (Adopted from IHI

white paper) [22].

|

Another distinct feature of a collaborative is to

spread the improvement beyond the initial teams to larger organizations

and regions and countries. A collaborative usually concludes with a

final package of interventions that have been field-tested and proven to

yield results in a particular setting complemented by a set of

organizational learning that facilitates achieving those results.

Dissemination of information gathered from Collaborative QI activities

through online tools such as CNN-EPIQ’s Virtual Research Community, the

VON’s NICQ pedia or Pediatrix’s Quality Steps system, Pediatrix-University

Web site and so on widen the scale of implementation packages across

clinical settings [13,26]. Collaborative QI offers a pragmatic way to

improve performance of healthcare delivery both at hospital and

community level. The power of collaborative research lies in multiple

centers performing the same project locally and submitting their results

to a coordinating team. The sample size is therefore bigger, and the

results are more generalizable [27].

Challenges in Implementation of a QI Collaborative [22,28]

Current review of evidence suggests that success of

running a quality improvement collaborative depends on following

factors.

• Participating teams which consist of

multi-professionals, like nursing staff are more likely to implement

process changes.

• Administrative and leadership support at

participating units in fostering a culture of quality improvement.

• Geographical span of participating units might

influence success of collaboratives, even though evidence on

comparative efficacy of regional versus national

collaboratives is lacking.

• Nature of participating centers influences

success of collaborative, if all are of similar nature like

(tertiary or primary care), then there is more probability of

completing collaborative.

• Availability of continuous and reliable quality

data on measurement of practices and change is another bottleneck in

the implementation of collaborative QI, maintaining data quality.

Legal and ethical framework regarding data sharing and public

display of collaborative QI data needs to be addressed clearly.

• Not enough evidence to suggest if one

particular method of contact (physical versus online or

email) between the participating centers has influence on

collaborative successes.

• Challenges to health care organization include

convincing people involved in owning up problem solving, aligning

regional quality improvement priorities with those of individual

centers and getting data collection and monitoring systems right.

Organizational barriers can be technical, structural, psychosocial,

managerial, and related to goals and values [29].

• Sustaining the results of Collaborative Quality

Improvement efforts can be particularly challenging and requires

systematic, thoughtful planning and action to ensure that the

changes result in permanent work culture improvement [14].

An Example of Collaborative Quality Improvement in

India

In 2012, a Neonatal collaborative consisting of six

of the best public and private neonatal intensive care units in the

country came together to decrease Healthcare-associated infections.

ACCESS Health International facilitated this with technical assistance

from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement. The collaborative

objective was to decrease healthcare associated infections (HAIs) by

transparently comparing outcomes, sharing best practices, testing

changes for resolving barriers identified by application of problem

analysis tools and acceleration of improvement by learning from each

other. Several changes were done to decrease incidence of HAIs by

increasing the reliability of processes like hand hygiene, aseptic

insertion and maintenance of peripheral and central venous line, aseptic

preparation of parenteral nutrition and intravenous fluids. The

participating hospitals met once every 6 months over a period of 18

months for learning sessions. The first meeting provided an opportunity

for all the clinical leaders to agree upon operational definitions of

the outcome, process measures and capability was built on quality

improvement methods and tools. This helped create a standardized

surveillance mechanism for recording healthcare associated infections.

Across all six hospitals, data was collected along with testing of

changes over a period of 12 months. Four out of six hospitals continued

the surveillance mechanism and improvement activity even after the

collaborative ended, demonstrating the sustainability of the

intervention. The hospital with the highest incidence of healthcare

associated infections showed the maximum improvement with more than 50%

reduction from baseline in both microbiological and clinical blood

stream infections per 1000 patient days. The collaborative approach with

adoption of shared practices, strong engagement of clinical leaders, and

utilization of data were thought to be key reasons for this improvement.

The results of this collaborative led to the scale up of QI work across

two Indian states as the Safe Care Saving Lives project [30].

Scope for Indian Collaborative

Below mentioned are examples of Indian collaboratives

where data was collected and variation in outcome and clinical practices

were measured in NICUs across the country. They can form the basis of

future collaborative QI by shared learning.

National Neonatal Perinatal Database Network (NNPD):

Over a time period of 1995-2003, data collected for about 200,000

neonates across various NICUs in India showed improved neonatal outcomes

over three different time periods, probably attributed to improved care

practices. Across NICUs from a similar geographical area and having

similar disease burden, mortality and morbidity outcomes varied. This is

ideal platform for planning QI collaborative across different health

care practices and outcomes.

VLBW Infant Survival in Hospitals of India (VISHI):

In a more recent collaborative work across India, 11 different level

3 NICU units collaborated for over a period of one year. In this

collaborative effort, outcomes of VLBW infants admitted across different

NICUs were studied. Standardized neonatal mortality rates varied across

different neonatal centers, thus emphasizing the need to start QI

collaborative practice to reduce variability in clinical practice

responsible for varied outcomes [31].

Indian Neonatal Collaborative (INNC): A group of

hospitals led by PGIMER, Chandigarh have created a database platform for

collecting data on neonatal quality indicators and processes. Nearly 12

centers are contributing data to this online database. Centers with at

least 100 VLBW admissions per annuum are eligible for this

collaborative. The live reporting of quality indicators on a dashboard

from this database would form a platform for network centers to initiate

unit based and collaborative improvement projects [32].

All collaborative or networking initiatives in our

country have so far collected invaluable data on neonatal survival,

morbidities across the country. Going beyond passive data collection, a

road map needs to be put in place to establish collaboratives across the

length and breadth of the country to address pertaining problems of VLBW

outcomes, antibiotic resistance, birth asphyxia and many more. Initially

providers need to be identified who are passionate and knowledgeable

about QI. For any quality initiative to succeed the clinical team must

be enthusiastic about improving, transparent and honest in sharing data,

and willing to learn and make practice changes to support improvement.

Ultimately collaborative QI needs to be integrated in day-to-day work

culture (Box 1).

|

Box I The Future Directions for Quality

Improvement in Healthcare of Preterm*

• Including parents of infants in the

implementation of QI collaborative projects, this will achieve

true multidisciplinary nature of teams.

• QI should be a part of medical curriculum,

thus inculcating the culture of collaborative QI very early in

to the day to day life of future lead clinicians and

administrators.

• Research should focus on determining

effectiveness of different approaches of collaborative like

‘breakthrough’ versus ‘communities of practice’.

• Collaboratives are very intense in terms of

manpower and cost, hence there is a need to determine their cost

effectiveness in long term.

*From reference 22.

|

In our country, identifying and creating QI teams at

service delivery or unit level will form the first step in starting

collaborative QI projects. QI team members will work together to

understand their local priorities at unit level, analyze their

processes, test and implement changes to improve performance, and

monitor results. Such QI teams can then be connected to create a

platform to share results, innovations, and challenges and to learn from

one another. Sharing outcome variations and clinical challenges in

different NICU units, will avoid duplication of efforts in solving

problems and provide an opportunity to improve service delivery. Hand

holding or ‘coaching’ will ensure that QI teams function optimally,

possessing knowledge and skills in both technical content related to the

improvement objectives and quality improvement tools.

Contributors: SM, SK: literature search and

drafted the manuscript; PK, DC, AT: guided the framework of the

manuscript and critical review. All authors approved the final version

of manuscript.

Funding: None; Competing interest: None

stated.

References

1. Batalden PB, Davidoff F. What is "quality

improvement" and how can it transform healthcare? Qual Saf Health Care.

2007;16:2-3.

2. Soll RF. Evaluating the medical evidence for

quality improvement. Clin Perinatol. 2010;37:11-28.

3. Glasziou P, Ogrinc G, Goodman S. Can

evidence-based medicine and clinical quality improvement learn from each

other? BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20:i13-17.

4. Porter ME. What is value in health care? N Engl J

Med. 2010;363:2477-81.

5. National Neonatology Forum: Report 1995: National

Neonatal Perinatal Database network. New Delhi: 1996.

6. National Neonatology Forum: National Neonatal

Perinatal Database. Report of the year 2000. New Delhi, 2001.

7. National Neonatology Forum: National neonatal

perinatal report of the year 2002. New Delhi, 2005.

8. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of

Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System

for the 21st Century. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US);

2001. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK222274/.

Accessed April 18, 2018.

9. Lasswell SM, Barfield WD, Rochat RW, Blackmon L.

Perinatal regionalization for very low-birth-weight and very preterm

infants: A meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;304:992-1000.

10. Schouten LMT, Hulscher MEJL, van Everdingen JJE,

Huijsman R, Grol RPTM. Evidence for the impact of quality improvement

collaboratives: Systematic review. BMJ. 2008;336:1491-4.

11. Horbar JD, Rogowski J, Plsek PE, Delmore P,

Edwards WH, Hocker J, et al. Collaborative quality improvement

for neonatal intensive care. NIC/Q Project Investigators of the Vermont

Oxford Network. Pediatrics. 2001;107:14-22.

12. Payne NR, Finkelstein MJ, Liu M, Kaempf JW,

Sharek PJ, Olsen S. NICU practices and outcomes associated with 9 years

of quality improvement collaboratives. Pediatrics. 2010;125:437-46.

13. Walsh M, Laptook A, Kazzi SN, Engle WA, Yao Q,

Rasmussen M, et al. A cluster-randomized trial of benchmarking

and multimodal quality improvement to improve rates of survival free of

bronchopulmonary dysplasia for infants with birth weights of less than

1250 grams. Pediatrics. 2007;119:876-90.

14. Lee SK, Aziz K, Singhal N, Cronin CM, James A,

Lee DSC, et al. Improving the quality of care for infants: A

cluster randomized controlled trial. CMAJ Can Med Assoc J J Assoc

Medicale Can. 2009;181:469-76.

15. Lee HC, Kurtin PS, Wight NE, Chance K,

Cucinotta-Fobes T, Hanson-Timpson TA, et al. A quality

improvement project to increase breast milk use in very low birth weight

infants. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e1679-87.

16. Ozawa M, Yokoo K, Funaba Y, Fukushima S, Fukuhara

R, Uchida M, et al. A quality improvement collaborative program

for neonatal pain management in Japan. Adv Neonatal Care.

2017;17:184-91.

17. Spence K, Henderson-Smart D. Closing the

evidence-practice gap for newborn pain using clinical networks. J

Paediatr Child Health. 2011;47:92-8.

18. Johnston AM, Bullock CE, Graham JE, Reilly MC,

Rocha C, Hoopes RD, et al. Implementation and case-study results

of potentially better practices for family-centered care: The

family-centered care map. Pediatrics. 2006;118:S108-14.

19. Baer VL, Henry E, Lambert DK, Stoddard RA,

Wiedmeier SE, Eggert LD, et al. Implementing a program to improve

compliance with neonatal intensive care unit transfusion guidelines was

accompanied by a reduction in transfusion rate: A pre-post analysis

within a multihospital health care system. Transfusion (Paris).

2011;51:264-9.

20. Lee HC, Lyndon A, Blumenfeld YJ, Dudley RA, Gould

JB. Antenatal steroid administration for premature neonates in

California. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:603-9.

21. The_improvement_collaborative. Available from:

https://www.usaidassist.org/sites/assist/files/the_improvement_

collaborative.june08.pdf. Accessed May 29, 2018.

22. IHI Breakthrough Series whitepaper 2003.

Available from: http://www.ncpc.org.uk/sites/default/files/Anita_IHI

Break throughSerieswhitepaper2003.pdf. Accessed April 18,2018.

23. Improvement Collaboratives in Healthcare.

Available from:

https://www.health.org.uk/sites/health/files/Improvement

CollaborativesInHealthcare.pdf. Accessed June 15, 2018.

24. Gould JB. The role of regional collaboratives:

the California Perinatal Quality Care Collaborative model. Clin

Perinatol. 2010;37:71-86.

25. Langley GL, Moen R, Nolan KM, Nolan TW, Norman

CL, Provost LP. The Improvement Guide: A Practical Approach to Enhancing

Organizational Performance. 2nd ed. San Francisco, California, USA:

Jossey-Bass Publishers; 2009.

26. Lee SK, McMillan DD, Ohlsson A, Pendray M, Synnes

A, Whyte R, et al. Variations in practice and outcomes in the Canadian

NICU network: 1996-1997. Pediatrics. 2000;106:1070-9.

27. Kilo CM. Improving care through collaboration.

Pediatrics. 1999;103:384-93.

28. Wells S, Tamir O, Gray J, Naidoo D, Bekhit M,

Goldmann D. Are quality improvement collaboratives effective? A

systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27:226-40.

29. Ziegenfuss JT. Organizational barriers to quality

improvement in medical and health care organizations. Qual Assur Util

Rev.1991;6:115-22.

30. Safe Care, Saving Lives. ACCESS Health Int.

Available from: http://accessh.org/project/safe-care-saving-lives/.

Accessed April 18, 2018.

31. Investigators VIS in H of I (VISHI) S, Murki S,

Kumar N, Chawla D, Bansal A, Mehta A, et al. Variability in

Survival of Very Low Birth Weight Neonates in Hospitals of India. Indian

J Pediatr. 2015;82:565-7.

32. Indian Neonatal Collaborative. Available from:

https://innc.org/. Accessed April 18, 2018.

|

|

|

|

|