Quality improvement (QI) is defined as the combined

and unceasing efforts of everyone involved in healthcare including

providers, patients and their families, researchers,

planners and administrators to make changes that will

lead to better patient outcomes, better health system performance and

better professional development [1]. Better quality of care (QoC)

ensures that the healthcare provided is safe (avoids harm), effective

(evidence-based best practices), patient centred (care that respects

patients and their preferences), timely (avoids unnecessary delays),

efficient (avoiding wastage) and equitable. QI also helps one to

translate best clinical and scientific evidences into clinical practice.

The key ingredient of any QI initiative is the ‘change’ (context

specific improvement) that is proposed and the ‘methodology’ by which

the change is introduced [1]. QI initiatives in low- and middle- income

countries (LMIC) targeting small and sick neonates have shown benefits

in the form of reduction in neonatal mortality and morbidity [2].

However, overburdened staff and lack of sufficient equipment were

identified as the most common barriers during implementation [2].

While a number of approaches can be used for QI

initiatives, some general principles hold true for all of them. These

include a thorough understanding of the problem to be addressed, the

system and processes that prevail within the unit, appropriate data

collection, choosing suitable changes, executing them, and finally

evaluating and measuring the impact of such changes. All these can be

accomplished only with good leadership support, staff engagement,

motivation and team work. In this article, we share a number of QI

initiatives undertaken in the neonatal unit of our institute and

elaborate our learning from them.

Quality Improvement Journey at Our Center

Setting: Our Neonatal intensive care unit

(NICU) caters to an average of 2800 inborn neonates, in 10 bedded level

III, 12 bedded level II, 8 bedded kangaroo care unit or in the

rooming-in beds. Most neonates are born to mothers with high risk

obstetric conditions and approximately a quarter of them require NICU

admission. NICU team includes highly skilled nurses, four full-time

faculty, fellows undergoing super-speciality neonatal training and

rotating pediatric residents and other support staff.

Way back in 1980s, AIIMS NICU achieved a marked

reduction in neonatal mortality rate (NMR) from 36.6 per 1000 live

births in 1985 to 23.9 in 1986, just by introducing a few changes in

routine practice- (use of intravenous cannula in place of butterfly

needles, reducing intravenous fluid usage, stopping the use of stock

solution, not admitting caesarean babies for ‘observation’, meticulous

adherence to asepsis and promotion of breastfeeding) [3]. This was in

fact a quality improvement activity based on common sense and clinical

acumen but little did we know about its science and implementation then.

The data collected was part of the monthly morbidity and mortality

report. Similarly, there are reports from other parts of country [4] and

abroad [5] wherein implementation of simple interventions (e.g.,

rational admission policy and antibiotic usage, curbing non-essential

routine investigations and interventions, focus on asepsis and training

of nurses) have led to reduced neonatal mortality. These are examples of

‘lean principles’ – whereby better patient outcomes was created by

decreasing non-value added interventions/waste and fewer resources.

While there is no dearth of evidence, what afflicts

most LMIC settings including ours is the struggle to implement them in

practice: the knowledge-implementa-tion gap. This is important because,

while there may be many approaches to implement an evidence; the best

approach in a given setting cannot be determined without understanding

why certain practices and policies prevail within the setting and the

sentiments of people whose behavior we wish to change [6]. We at AIIMS

strived to implement evidence-based practices, succeeded in some, failed

in many but did not formally analyze failures and perhaps focussed more

on outcomes rather than processes.

Learning the science and art of QI: This outlook

certainly got more refined when we embarked on a journey of providing

quality care in a systematic way in August 2015, under the leadership of

the Director of AIIMS. A team comprising of a faculty, a nurse educator

and a resident from the pediatrics department attended a seminar on QI

and brought home clinical wisdom and enthusiasm to initiate QI

activities. They did their first QI project in NICU and tasted success.

QI was infectious; with early and obvious improvements, more people

wanted to be part of the process. Thus with more interest gathering,

participatory learning sessions (3-4 hours each) were organized to guide

members in the scientific way of doing QI. Initially five departmental

teams participated at the first workshop wherein teams brought problems

to work on and went home with an aim statement and to collect a few

baseline data. They formed local teams and came up with change ideas.

They were then taught to test these ideas in small Plan-do-study-act

(PDSA) cycles and to see if the changes led to improvement. The teams

met fortnightly to share progress and help out each other. More help

came from agencies like USAID Applying Science to Strengthen and Improve

Systems (ASSIST) Project and Institute of Healthcare Improvement (IHI),

which hand-held many departmental teams, conducted workshops, webinars

and arranged platforms for sharing QI work. Once a few QI projects were

completed, there emerged champions and local leaders in various

departments who then led the change movement. Frontline workers became

involved and better patient outcomes, client satisfaction and a sense of

fulfilment fuelled more QI projects. In the following paragraphs, we

describe various QI activities done in the NICU.

Improving the Rates of Hand-hygiene – Our Initial QI

Hand-hygiene (HH) is the most effective strategy in

reducing healthcare-associated infection in the unit. AIIMS NICU has a

very strong culture of implementing asepsis routines including HH, yet

the rates remained around 60% similar to most units with rates of 50% or

less [7]. We wanted to implement measures in a step-wise fashion to

improve compliance.

Implementation and evaluation: We designed a

prospective before-after study [8]. The intervention consisted of 4

steps as listed: step 1: standard teaching of health care providers with

posters, videos and self-learning module; step 2: face to face

interaction with practical demonstration and appreciation of hand

hygiene champions of the week; step 3: closed circuit television (CCTV)

monitoring; and step 4: CCTV monitoring with individual feedback for the

missed opportunities of hand hygiene. Each phase of intervention lasted

4 weeks. The compliance with HH was observed by trained research nurses

for the 5 moments of HH at various opportunities. The baseline HH

compliance in the unit was 61.8%, which improved significantly to 77%

after implementation of all 4 steps in a stepwise manner (relative

change 25%, 95% CI: 18% to 32%).

Learning and implications for practice: In

this improvement effort, we focussed on the process – namely performance

of HH and chose all the change ideas at the outset. There is a

possibility that the improvement we saw reflected Hawthorne effect of

being observed and fear of being monitored by CCTV cameras. While

adherence to HH was monitored continuously, the improvement was not

displayed to motivate everyone in the unit. We also did not analyze the

possible causes of poor compliance, barriers in implementation or make

efforts to sustain the improvement. However, the final study result

motivated all.

Improving Exclusive Mother’s Milk Feeding Rates among

Preterm Neonates

Exclusive human milk feeding in preterm

neonates is associated with lower rates of necrotizing enterocolitis

(NEC), sepsis, lesser rehospitalization rates and better

neurodevelopmental outcomes [9]. Early expression of mother’s milk

particularly within 6 hours after delivery and frequent expression are

associated with lactation beyond 40 weeks’ gestational age [10].

However, in reality lactation is delayed for mothers delivering preterm

babies due to various reasons like, being separated from the neonate,

illnesses that preclude oral feeding, maternal anxiety and lack of

support. Despite being very proactive for breast milk feeding in our

NICU, we found that even on postnatal day 7 of life, only 12.5% of all

admitted preterm neonates were on exclusive mother’s milk

feeding. We desired to increase the proportion of neonates

receiving mother’s own milk at postnatal day 7 from the current

rate of 12.5% to 30% over a period of six weeks [11].

Implementation and evaluation: A QI team

comprising of a faculty, two resident physicians, a nurse educator and

two senior staff nurses explored the reasons for poor breastmilk

expression using fish-bone analyses. Baseline data collected for initial

7 days included time of first expression of breast milk (EBM) in mothers

delivering preterm neonates, daily amount of EBM and percentage of

neonates on exclusive mother’s milk feeding in NICU. Poor awareness

among healthcare providers and lack of maternal counselling were

identified as most important causes for the problem. Hence as a change

solution, a comprehensive postnatal counselling was implemented wherein

the bed-side nurse was assigned the responsibility to initiate the first

milk expression within 6 hours of delivery. The mother was educated with

videos on breast feeding and encouraged to pump every 4-hourly as soon

as she was stable postpartum. Successive PDSA cycles focused on staff

motivation and the primary nurse whose neonate achieved exclusive breast

feeding on or before 7

th day

of life was awarded with a certificate. Run charts were displayed

showing percentage of neonates each day on exclusive EBM. This QI also

addressed the supply chain issues like the availability of breast pump

and its accessories as well as a refrigerator for milk storage both in

NICU and postnatal wards.

The NICU team finally succeeded in their efforts.

While the time to first expression of breast milk was 48 hours in the

baseline phase, milk expression began within 3 hours of delivery after

the intervention. The proportion of neonates on exclusive mother’s milk

increased from 12.5% to 81% on day 7 of life. A re-evaluation one year

after implementation showed that the success was sustained with

exclusive EBM rates of 80% on day 7 of life.

Learning and implications for clinical practice:

This QI initiative is an example wherein front-line workers (nurses in

this case) were empowered for initiating milk expression and driving the

entire QI to increase EBM use in NICU. The QI tools used in this

initiative include fish-bone analyses and PDSA cycle for implementation

of change ideas. The entire QI could be done with the available

resources and with continued staff motivation, the team sustained their

efforts even a year later.

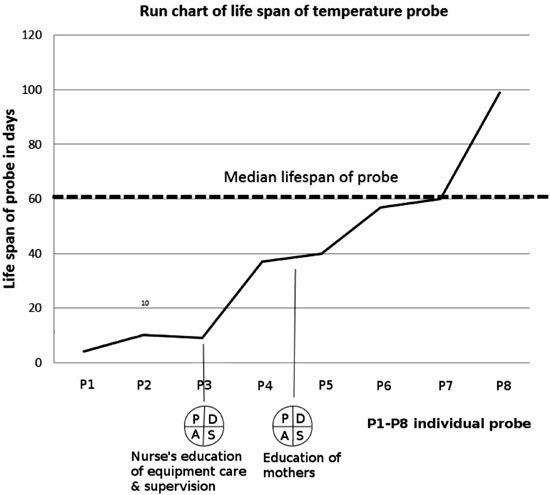

Improving Life of Radiant Warmer Probes in NICU

Equipment used in the NICU are costly and failure or

break-down of equipment or its parts affect patient safety and increase

the cost of care. We found that there was frequent breakage of radiant

warmer temperature probes in NICU with one particular unit requesting a

new probe once in 9 days. We wanted to explore and rectify this

equipment failure using QI methods.

Implementation and evaluation: A team was formed

including faculty in-charge as team leader, 4 nurses and a resident

doctor. The potential reasons for temperature probe breakage were

evaluated using 5 whys (Table I).

TABLE I Five Whys Analyses for Deriving the Root Cause of a Problem*

|

Whys |

Question |

Answer what caused the situation |

|

1. |

Why only one NICU was having this specific equipment failure? |

Because this NICU caters to stable growing preterm babies

|

|

2. |

Why probes of stable babies are damaged more often? |

Because, these babies are taken off the warmer more frequently

for kangaroo mother care |

|

3. |

Why probes get damaged with frequent disconnection? |

Because care providers do not know that probes are costly

that they often allowed mothers to do the task themselves |

|

4. |

Why do care providers not aware of this? |

Because no one provided in-service orientation of nurses on

equipment maintenance |

|

5. |

Why was no orientation provided? |

No one thought that this was important. This is the root cause

of the problem in hand. |

The ‘SMART’ (Specific, Measurable, Applicable,

Realistic and Timely) aim was to increase the life span of temperature

probe from the current lifespan of 9 days by 80% over a period of 8

weeks. The change ideas involved providing a refresher course for nurses

on equipment care, supervising mothers and junior nurses while handling

probes and tracking probe breakage. After implementing the PDSA cycle 1,

the life of temperature probe increased up to 40 days, which was not as

good as expected. Exploring the reasons, it was noted that mothers

needed more support and can be taken as partners in QI. In 2

nd

PDSA cycle, the bedside nurses provided face to face education of

mothers on taking care of warmer equipment and made it a point to

discuss status of temperature probes during nursing hand-over in each

shift. After the 2nd PDSA

cycle, the minimum time interval between two temperature probe

break-down increased to median of 60 days as indicated by run chart (Fig.

1).

|

|

Fig. 1 Annotated run chart showing

life span (in days) of temperature probe in the NICU. P1-P8 on

the x axis indicates an individual temperature probe. The dashed

line indicates median life span.

|

Learning and Implications for clinical practice:

This QI initiative began because one astute nurse recognized that an

order for new temperature probe was being placed too often. She had to

convince the other staff that something was wrong. Unless people

recognize the problems and are involved in initiating the change, there

is often resistance. The team used 5-whys analyses to identify the major

cause of probe breakdown. They came up with solutions, tested them to

see if it worked and then implemented those that worked. Following this

QI, recommendations were made in the unit to provide regular in-service

training of nurses on proper equipment use and its maintenance.

Involvement of mothers as partners in care as suggested by this QI

initiative improved the success rate.

Prevention of Admission Hypothermia Among Preterm

Neonates

Hypothermia is an important contributor of neonatal

mortality and morbidity. During an audit, we observed that

majority of inborn preterm neonates <32 weeks gestation admitted to our

NICU were hypothermic with mean admission temperature of 35.6°C despite

the use of plastic wraps, attention to warmth during resuscitation and

transport. We wanted to improve the mean admission temperatures (AT) of

preterm neonates from the existing baseline of 35.6°C to normal range

(36.5-37.5°C) by implementing all the components of an evidence based

thermoregulation bundle in a stepwise manner using PDSA cycles over a

period of 11 months [12].

Implementation and evaluation: A

multidisciplinary QI team was formed who analyzed the causes of

hypothermia using fish bone analyzes (Web Fig. 1).

During an observation period of three months, a dedicated nurse observed

the delivery room activities and a Pareto chart (Web

Fig. 2) was constructed to identify those few important

practices that needed to change. The Pareto chart revealed that the

application of plastic wrap at birth was not proper in a majority of

cases. Residents explained that the cling wraps crumpled when they tried

to wrap the babies. Thus the changes in PDSA cycle 1, included the use

of plastic bags instead of cling wraps for resuscitation. However, a

look at the run chart revealed that hypothermia was persisting. The team

discussed the issues with resident physicians and nurses and noted that

the plastic bag available in market was stiff and the cut ends remained

open exposing the neonate. Also the delivery room (DR) nurses were not

aware of this QI initiative. So in next cycle, the team reinstituted the

use of cling wraps but used a new way of application. The delivery room

nurses were educated on the importance of hypothermia and how they could

contribute to the initiative. In cycle-3, thermometers were installed in

DR to monitor room temperature and the team co-ordinated with nursing

assistants to ensure prompt transfer from DR to NICU. Frequent feedback

with run charts of AT and appraisal in monthly meetings were done to

ensure compliance and staff motivation in the post-intervention phase (4

months).

We studied a total of 79 preterm neonates during this

QI initiative and noted AT in the post-intervention period with mean AT

of 36.5°C and a significant drop in the incidence of moderate

hypothermia (axillary temperature between 32-36°C) from 50% to 12.5%. We

used a statistical process control chart for trending admission

temperatures over time and demonstrated both a sustained increase in

mean AT as well as decreased variability as reflected in the narrowing

of the control limits (Web Fig. 3). As a

balancing outcome, we did not notice any episode of hyperthermia or

increase in mortality among neonates.

Learning and implications for clinical practice:

This is an example of a complex QI study where team members

implemented a bundle of interventions in different regions of hospital

namely labour room, obstetric operation theatre and NICU. When too many

etiologies for a problem were noted in the fish-bone diagram, they used

the Pareto’s tool to identify those few important causes that contribute

most. The Pareto tool also called as ‘80-20 rule’ states that 20% of the

causes are responsible for 80% of the problems and can help one to focus

on the important few. The first PDSA was not successful but the

team innovated a new method in the second cycle. Some problems need

a multi-pronged approach or a bundle of interventions and one can

simultaneous test 2 or 3 change ideas as opposed to serial testing. The

other lesson from this QI was to involve all stake-holders from the

multiple areas for success. While we used run charts [13] for tracking

and display, we used the statistical process control charts (SPC) to

understand the process better. The SPC charts have an upper and lower

control line (±3 standard deviations) in addition to the central line

which represents the mean as opposed to the run chart where central line

represents median [14]. While both run charts and SPC charts can

visually display data over time and inform whether changes have resulted

in improvement, the SPC charts in addition tell us whether the process

is stable over time. A stable process, has most points near central

line, few points near control lines and none beyond control lines. If

points are above the control line, it indicates a special cause

variation due to changes introduced in the system that needs to be

investigated. There are other pointers to special cause variation too

[14]; and in our example we had eight successive points on the same side

of the centre line as an indicator.

Sustaining an improvement is important and in our

NICU we have implemented the following – regular monitoring of delivery

room temperatures, a checklist to ensure that all resuscitation supplies

and equipment are available and we use admission temperature as an

indicator of quality resuscitation, which is regularly audited for

feedback. Dutta, et al. [15] from India reported a similar QI

initiative to improve admission hypothermia in neonates wherein they

showed lesser hypothermia as well as reduced mortality and late onset

sepsis. The entire QI could be done without major cost, with no

additional staff or new equipment. All the change ideas focussed on

making the existing system and process of care easier for staff to

implement the interventions.

Reducing Breastfeeding Problems at Discharge

Breastfeeding problems are very common, almost 80% of

mothers experience one or more problems related to breastfeeding like

sore, cracked or flat nipples, painful or engorged breasts, difficulty

latching, feeling of decreased milk output etc. while in hospital

[16]. These problems, if not avoided or corrected with proper education

and support can even lead to early cessation of breastfeeding.

Breastfeeding in our postnatal mothers is primarily

assessed by resident doctors and counselling regarding specific or

anticipated problems is done individually at the bedside. Our postnatal

follow up clinic that runs all working days for 2 hours specifically

caters to neonates who are followed up within a couple of days after

discharge. We observed that up to 20-30% of mother-baby dyads presented

with issues related to breastfeeding. Hence we designed a QI initiative

to address this [17].

Our SMART aim was to reduce the incidence of breast

feeding problems at discharge from baseline of 75% to at least 37.5%

among mothers delivering term babies by implementing a post-partum

education package over a period of four months from September 2016 to

December 2016. A QI team was formed and two members (a nurse educator

and neonatal resident) objectively assessed breastfeeding among eligible

mothers in initial phase (4 weeks) using LATCH breastfeeding assessment

scores [18] and collected data on breastfeeding issues. Fishbone

analyses was done, and the team planned to introduce a learning package

for mothers. The nurses in post-natal wards were involved in teaching

activities (phase 2 lasting 4 weeks) which consisted of distributing

pamphlets and video demonstration on breastfeeding. Mothers’ perception

and acceptability of the education package was then assessed on a

5-point Likert scale at the time of discharge. In the phase 3 (2 weeks),

the team stressed on compliance with education package by having a

checklist attached to neonate’s file. Focused group discussions with

postnatal nurses and mothers were conducted to obtain feedback and to

identify barriers in implementation. In phase 4 (2 weeks), a lactation

nurse provided one to one support to all postnatal mothers in addition

and in phase 5 (4 weeks), videos were uploaded in mother’s cell phone

for repeated viewing and other measures were continued.

A total of 330 mother-infant dyads were enrolled in

all the phases of QI. Incidence of breastfeeding problems at discharge

gradually decreased from phase 1 (baseline) to phase 5 from 72.6% to

6.8% (P<0.001) (Web Fig. 4). Compared

to baseline, the proportion of mothers with LATCH score >8/10 at end of

final phase (RR 3.8; 95% CI 2.7-5.5, P< 0.001) as well as each of

the individual phases were significantly greater. The compliance with

discharge checklist increased from 29.8% to 100% and mothers felt that

the educational package had utility as well as acceptability, with

43-65% of mothers strongly agreeing in favor of the education bundle.

Learning and implications for clinical practice:

This QI initiative addressed breastfeeding problems in postnatal mothers

by successful implementation of educational intervention driven by

stepwise rapid cycle PDSA based approach. As outcome measures of

improvement, the team used percentage of mother-infant dyads with

problems at discharge and LATCH score to objectively assess

breastfeeding. As process measures, they tracked the compliance with the

interventions using a checklist. The team used p-chart (p stands for

proportion) to monitor the proportion of mothers with breastfeeding

problems. Similar to a control chart, p-chart also has a central line

which corresponds to the mean proportion and 2 control lines

corresponding to three standard deviations (SD) around the mean. A

special-cause variation that requires investigation is indicated by

point (s) outside the control limits. Web Table 1 lists

the various QI projects done at AIIMS NICU.

Moving Forward With QI Activities

After multiple QI efforts, the NICU nurse educator

emerged as a champion who further supervised more QI work like,

increasing the duration of kangaroo care for preterm neonates in NICU,

decreasing medication errors, antibiotic stewardship and streamlining of

post-natal follow up clinic. QI had also been topics of dissertation

work for postgraduates in the department; the QI work on preventing

admission hypothermia, resolution of breast feeding problems in the

post-natal ward (both discussed above) and improving oxygen saturation

targeting among neonates on oxygen therapy are dissertation work done by

postgraduates. An ongoing QI dissertation work focuses on implementing

potentially best practices in the first week of life among preterm

neonates to reduce the incidence of bronchopulmonary dysplasia.

Dissemination and capacity-building: AIIMS, a WHO

Collaborating Center for Newborn health disseminates QI to other

organizations through its on-line resources, face-to-face workshops and

the Point of Care Continuous Quality Improvement (POCQI) module. A

dedicated website (http://aiimsqi.org/) on quality improvement

provides free resources for teaching and learning QI, and as a platform

for capacity building of teams and sharing QI work. The site also has

short videos and posters of various QI projects done in the Institute.

Many SEARO (South East Asian Regional Organization) countries

participated in a Regional Workshop for Improving Quality of Hospital

Care for Maternal and Newborn Health in May 2016 at New Delhi and have

initiated QI work in their areas. QI project power-point template is

freely available in the site that teams can use as a framework for QI

work.

Teaching and Research in QI: QI is taught to

undergraduates and nursing students at AIIMS. Postgraduates are

encouraged to be part of QI teams in clinical areas and as topics for

research or dissertation work. A good starting point for a dissertation

or thesis on QI work is a single-centre prospective study with a

pre-post design. The focus should be on implementation rather than

testing whether certain practices are effective or not. So careful

planning is essential to understand the existing processes, to identify

how and why the current practices differ from recommended or

evidence-based practice and to involve all stake-holders who may

influence implementation. The team should identify the data that needs

to be collected to measure improvement before study begins. Broadly this

includes process measures (measurement of processes to see if the

changes are being implemented), outcome measures (impact of the changes

on patient or provider outcomes) and balancing measures (unexpected

outcomes or changes both beneficial or harmful that are introduced

either in the same system or other parts of system due to improvement

efforts) [19]. For example, if a team plans to implement skin-to-skin

care (STS) at birth for neonates, exclusive breastfeeding rates at

discharge can be taken as outcome measure, the percentage of eligible

mother-baby dyad experiencing STS, number of STS checklists filled per

month and time to first breastfeeding can be process measures and

incidence of acute life threatening event in neonate (desaturation or

bradycardia) during STS can be chosen as balancing outcome. Published

guidelines are available for reporting QI work in order to improve the

completeness and accuracy of reporting so that improvement efforts can

be reproduced at other suitable settings [20]. It is equally important

to publish QI work to share one’s improvement experiences, so that

others working on similar problems can adopt or adapt the change ideas

without wasting time, effort and money testing the same ideas.

Learning From QI at AIIMS

What started as small projects in a few departments

mushroomed into several projects wherein several other departments like

Rajendra Prasad Ophthalmic Sciences Centre, Emergency medicine,

Pediatrics, Obstetrics, Cardio-Neuro centre and Jai Prakash Narayan Apex

Trauma Institute also participated. QI made people recognize the

problems in their system, utilize various tools (process mapping,

fish-bone analyses, 5 whys) to understand the cause, come up with

changes or solutions tailored for their system, test the changes in

small scale over a short period or on few patients (PDSA cycles), and

adapt/adopt or abandon the changes and finally implement them. People

understood that not all changes lead to improvement and collecting data

to assess baseline performance and reassessing performance over time

using annotated run charts or statistical process control charts help in

differentiating day-to-day variations from improvement. Importantly, the

teams learnt the scientific way of doing QI activities. There was a lot

of learning from each project (both success and failure) that people

shared in common meetings. Salient learning points are given below:

Bottom up approach: We created a culture for QI

in the unit by building conviction among front-line workers. The human

element is the most important component of any QI success story and

staff motivation and engagement is essential to work towards a common

goal [21]. Each team member contributes to improvement and in many

situations, we observed practical change ideas not from leaders but from

front-line staff. In our case, NICU nurses identified the problem of

frequent temperature probe breakdown and came up with change ideas like

empowering the bedside nurse to help mothers with milk expression; the

housekeeping staff volunteered in hypothermia QI and offered timely and

quick transport of neonates to NICU, and mothers of admitted neonates

joined as partners in some QI initiatives.

Understand the system and eliminate waste:

Traditionally, the solution to most problems are handled by increasing

human or material resources; but in healthcare system in which resources

are limited, focussing one’s attention to understanding the system to

identify the root cause and eliminating the redundant and wasteful

processes can help to utilise resources effectively [22]. In our case,

breastfeeding counselling by multiple team members with different

messages, lack of supplies in the delivery room despite their

availability etc. could be rectified when the counselling became more

standardized using pamphlets/videos and a checklist was used for

arranging supplies in the delivery room. Behavioral change of

healthworkers is also important in eliminating waste and facilitating

this change will require education, training, motivation and feedback.

Step-up and then scale-up: It is very essential

that initial projects be simple, doable, patient-centric and under the

control of the team members. Disease processes or problems with

multifactorial etiologies take time or produce no improvement at all.

Undertaking such projects at the outset would demotivate staff who may

feel over-burdened and incapacitated. Our team felt comfortable to use

the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA)

cycle for rapid cycle improvement and changes were accomplished through

small and frequent PDSAs [23]. Only change ideas that were tested on a

small population and adapted for local context were implemented on a

large scale. Building sustainability in each project is so important

[24], that improvements are maintained in long run and the changes

become a new norm in the unit. This involves making changes in the

system itself, use of visual reminders, posters, score cards and

identifying champions who would lead the change movement. In our NICU,

the following system changes were implemented to sustain the

improvements; regular in-service training on equipment handling for

nurses and residents, installation of room thermometers in delivery room

and tracking of temperatures each shift, charting admission temperatures

in the NICU admission register as a quality indicator, and use of videos

for breastfeeding counselling.

Celebrate and share success: Having QI meetings

both within and between departments helps to show case activities and

rally slow movers to gain pace. The QI teams from various departments

attended learning sessions and workshops organized by AIIMS from time to

time where they had the opportunity to learn from experts, presented

their work and shared their experiences. The teams also met face-to-face

with other teams, participated in webinars and conference calls, and

presented their work at conferences. Teams learnt that they could learn

and achieve more by collaboration than working in silos [25].

Time and patience surpasses hurdles: We

understood early that problems have to be solved by a team of people and

getting people on board could sometimes be challenging. Such factors

include staff misunderstanding the principles of QI, feeling

over-burdened with data collection, fear of being monitored or blamed

for poor performance or just an inertia to change. In our hand hygiene

QI, we noticed nurses’ resentment against being monitored, in our

exclusive breast feeding QI, only a couple of nurses from one NICU were

involved. Thus initially like-minded ones teamed up but with time even

the disinterested become passionate about change. Nurses participating

in QI mentored fellow nurses, and with time came up with ways to collect

or add essential data in the nursing flow sheet itself thus decreasing

additional paperwork and burden.

Organizations striving to improve their outcomes

should initiate and support quality improvement activities. The

important requisites for successful QI ventures are listed in Box

I.

| |

|

Box I Key Messages for Organizations

Planning QI Activities

Leadership support with a vision for quality

improvement. Leaders should encourage and motivate staff

involved in QI and also support shared goals for performance.

Capacity building of staff for QI by training

them in the art and science of QI. Encourage teams to attend

learning sessions and workshops. Allow staff to set aside time

for improvement activities apart from their work.

Empower teams to run and manage systems and

introduce changes at their level.

Dedicate time and resources to measure

performance over time. All QI work should be data driven.

Encourage all team members to openly discuss both success and

failure. Allow collaboration between teams in the organization.

|

Contributors: SS, AS: participated in QI, and

drafted the manuscript; MJ: supervised and implemented QI activities in

NICU, collected data; AT: supervised QI in NICU, data collection and

analyses; MJS: supervised QI in NICU, data collection and analyses; AKD,

RA: concept and design. Revised manuscript and were involved in QI

activities in NICU.

Funding: None; Competing interest: None

stated.

References

1. Batalden PB, Davidoff F. What is "quality

improvement" and how can it transform healthcare? Qual Saf Health Care.

2007;16:2-3.

2. Zaka N, Alexander EC, Manikam L, Norman ICF,

Akhbari M, Moxon S, et al. Quality improvement initiatives for

hospitalised small and sick newborns in low- and middle-income

countries: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2018;13:20.

3. Singh M, Paul VK, Deorari AK, Ray D, Murali MV,

Sundaram KR. Strategies which reduced sepsis-related neonatal mortality.

Indian J Pediatr. 1988;55:955-60.

4. Mukherjee SB, Bandyopadhyay T. Perinatal

mortality- what has changed? Indian Pediatr. 2016;53;242-3.

5. Darmstadt GL, Ahmed ASN, Saha SK, Azad Chowdhury

MA, Alam MA, Khatun M, et al. Infection control practices reduce

nosocomial infections and mortality in preterm infants in Bangladesh. J

Perinatol. 2005;25: 331-5.

6. Varkey P, Kollengode A. A framework for healthcare

quality improvement in India: the time is here and now! J Postgrad Med.

2011;57:237-41.

7. Pittet D. Improving compliance with hand hygiene

in hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2000;21:381-6.

8. Gopalakrishnan S, Agarwal R, Paul VK, Deorari AK.

Effect of stepwise interventions aimed at improving hand hygiene

compliance among healthcare providers in a level III neonatal intensive

care unit: Before and after study: Dissertation submitted to the faculty

of Department of Pediatrics, AIIMS, New Delhi 2015.

9. Johnston M, Landers S, Noble L, Szucs K, L V.

Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e827-41.

10. Furman L, Minich N, Hack M. Correlates of

lactation in mothers of very low birth weight infants. Pediatrics.

2002;109:e57.

11. Sethi A, Joshi M, Thukral A, Dalal JS, Deorari

AK. A quality improvement initiative: improving exclusive breastfeeding

rates of preterm neonates. Indian J Pediatr. 2017;84:322-5.

12. Sivanandan S, Jeeva Sankar M, Thukral A, Agarwal

R, Paul VK, Deorari AK. Quality initiative on implementation of golden

hour bundle to improve outcomes of preterm neonates <32 weeks gestation:

focus on thermoregulation: Dissertation submitted to the faculty of

Department of Pediatrics, AIIMS, New Delhi, 2016.

13. Perla RJ, Provost LP, Murray SK. The run chart: A

simple analytical tool for learning from variation in healthcare

processes. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20:46-51.

14. Benneyan JC, Lloyd RC, Plsek PE. Statistical

process control as a tool for research and healthcare improvement. Qual

Saf Health Care. 2003;12:458-64.

15. Datta V, Saili A, Goel S, Sooden A, Singh M, Vaid

S, et al. Reducing hypothermia in newborns admitted to a neonatal

care unit in a large academic hospital in New Delhi, India. BMJ Open

Qual. 2017;6:e000183.

16. Colin WB, Scott JA. Breastfeeding: Reasons for

starting, reasons for stopping and problems along the way. Breastfeed

Rev. 2002;10:13-9.

17. Mangla MK, Jeeva Sankar M, Deorari AK, Thukral A,

Agarwal R, Paul VK. Quality improvement study to reduce incidence of

breastfeeding problems at discharge in postnatal mothers who delivered

at term gestation: Dissertation submitted to the faculty of Department

of Pediatrics, AIIMS, New Delhi; 2017.

18. Jensen D, Wallace S, Kelsay P. LATCH: A

breastfeeding charting system and documentation tool. J Obstet Gynecol

Neonatal Nurs. 1994;23:27-32.

19. Mainz J. Defining and classifying clinical

indicators for quality improvement. Int J Qual Health Care.

2003;15:523-30.

20. Davidoff F, Batalden P, Stevens D, Ogrinc G,

Mooney S, Group SD. Publication guidelines for quality improvement in

health care: Evolution of the SQUIRE project. Qual Saf Health Care.

2008;17:i3-9.

21. Baker DP, Day R, Salas E. Teamwork as an

essential component of high-reliability organizations. Health Serv Res.

2006;41:1576-98.

22. Bentley TG, Effros RM, Palar K, Keeler EB. Waste

in the US health care system: A conceptual framework. Milbank Q.

2008;86:629-59.

23. Harolds J. Quality and safety in health care,

part I: Five pioneers in quality. Clin Nucl Med. 2015;40:660-2.

24. Barker PM, Reid A, Schall MW. A framework for

scaling up health interventions: Lessons from large-scale improvement

initiatives in Africa. Implement Sci. 2016;11:12.

25. Nembhard IM. Learning and improving in quality

improvement collaboratives: Which collaborative features do participants

value most? Health Serv Res. 2009;44:359-78.