|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2018;55:768-772 |

|

A Quality Improvement

Initiative for Early Initiation of Emergency Management for Sick

Neonates

|

|

Asim Mallick, Mukut Banerjee, Biswajit Mondal,

Shrabani Mandal, Bina Acharya and Biswanath Basu

From Department of Pediatrics, Nilratan Sircar

Medical College and Hospital, Kolkata, India

Correspondence to: Dr Mukut Banerjee,

Assistant Professor, Department of Pediatrics, Nilratan Sircar Medical

College and Hospital, Kolkata, India.

Email: [email protected]

Received: January 19, 2018;

Initial review: February 15, 2018;

Accepted: July 13, 2018.

|

Objective: To determine efficacy of Point-of-care

Quality improvement (POCQI) in early initiation (within 30 minutes) of

emergency treatment among sick neonates.

Design: Quality improvement project over a period

of twenty weeks.

Setting: Special Newborn Care Unit (SNCU) of a

tertiary care center of Eastern India.

Participants: All consecutive sick neonates ( ³

28 wk gestation) who presented at triage during morning shift (8 am to 2

pm).

Intervention: We used a stepwise

Plan-do-study-act (PDSA) approach to initiate treatment within 30 min of

receiving sick newborns. After baseline phase of one month, a quality

improvement (QI) team was formed and conducted three PDSA cycles (PDSA I

, PDSA II and PDSA III) of 10 d each, followed by a post-intervention

phase over 3 months.

Main outcome measure(s): Percentage of sick

babies getting early emergency management at SNCU triage.

Results: 309 neonates were enrolled in the study

(56 in baseline phase, 88 in implementation phase and 212 in post-

intervention phase). Demographic characteristics including birthweight

and gestational age were comparable among baseline and post intervention

cohorts. During implementation phase, successful early initiation of

management was noted among 47%, 69% and 80% neonates following PDSA I,

PDSA II and PDSA III, respectively. In comparison to baseline phase, the

percentage of neonates receiving treatment within 30 minutes of arrival

at triage increased from 20% to 76% (P<0.001) and the mean (SD)

time of initiation of treatment decreased from 80.8 (21.0) to 19.8 (5.6)

min (P<0.001) during post-implementation phase. Hospital

mortality (33% vs 15%, P=0.004) and need for ventilator

support (44% vs 18%, P<0.001) were also significantly

lower among post intervention cohort in comparison to baseline cohort.

Conclusion: Stepwise implementation of PDSA

cycles significantly increased the percentage of sick newborns receiving

early emergency management at the SNCU triage, thereby resulting in

better survival.

Keywords: Outcome, PDSA cycle, Point-of-care Quality

improvement, Triage.

|

|

P

erinatal and neonatal care have improved

remarkably over last few decades, resulting in substantial decrease in

national neonatal mortality rate; although, as per India Newborn Action

Plan, our goal is to achieve single digit neonatal mortality rate by

2030 [1,2]. This entails addressing the major causes of neonatal

mortality including cost effective strategy to solve the problems [3].

We detected various lacunae within our system (reducing delay in

emergency management of sick babies, ensuring early initiation of breast

feeding, reducing sepsis, ensuring KMC in eligible babies) which can be

addressed to reduce neonatal death.

Existing literature revealed that delay in emergency

treatment of sick neonates may increase the risk of mortality and long

term morbidities [4,5]. We also noticed that outborn babies referred

from distant places are more vulnerable to death in comparison to inborn

babies. These neonates were already compromised during the time of

referral. Even after reaching at referral centre, these already

compromised out born babies suffer further delay in initiating emergency

treatment due to various administrative and procedural reasons. A

relevant prospective cohort study observed similar findings and

documented that hourly delay in initiation of appropriate resuscitation

or persistence of hemodynamic abnormalities was associated with a

statistically significant increased risk of death among sick neonates

[4]. Based on this literature review, we planned to undertake a quality

improvement (QI) initiative to reduce the time of initiation of

management of neonates presenting to triage with emergency signs. We

prioritized reducing delay in emergency management of sick babies,

because it is important to patient outcomes, affordable in terms of time

and resources, easy to measure and under control of team members.

Methods

All consecutive sick neonates presenting at the

triage area during morning shift (8 AM to 2 PM) of a tertiary-care

medical center between February and June 2017, were approached for

enrolment. Neonates attending triage seeking emergency management during

the month of February 2017 formed baseline cohort; those during March

2017 formed implementation cohort; and those between April and June 2017

formed post-intervention cohort. Neonates with major congenital

malformations, neonates of <28 weeks of gestation and who expired

shortly (within thirty minutes) after receiving in the triage area were

excluded (Web Fig. 1). We defined a neonate as sick if

presenting with any of the emergency signs: Significant hypothermia (axillary

temperature < 35.5 ºC), apnea

or gasping respiration, severe respiratory distress [rate >70, severe

retraction (subcostal, intercostals and supraclavicular and suprasternal

retraction), grunt], central cyanosis, shock (cold periphery, Capillary

filling time >3s, heart rate >160/min) coma, convulsions or

encephalopathy [6]. The study was approved by the Institutional Review

Board of our institute and informed written consent was obtained from

parents of each enrolled neonate.

According to POCQI module [7] quality improvement

team comprised of total nine members (a team leader, one supervisor, an

analyser, two time keeper and communicator and four nursing staffs)

including two faculty members was formed. The team reviewed the

literature on evidence based practices for emergency management, and

presented the recommendations informally which were then agreed upon or

modified for local implementation.

Baseline phase and Root cause analysis: A

time keeper and communicator, who were not involved in managing the sick

neonate, were commissioned as observer to note the practices and the

time of initiation of emergency management by using stop watch in

triage. The doctors and the nursing staffs involved in management

received no feedback about the time of initiation of management of sick

neonates. During baseline phase, 20% (56) sick neonates attended SNCU

triage received treatment within 30 minutes and median time to initiate

emergency treatment was 80 minutes (60 to 104 minutes)

(Web Fig. 2).

We performed a cause and effect analysis of delay in

emergency care using process flow chart (Web Fig. 3),

fishbone diagram (Web Fig. 4) and a key driver diagram (Web

Fig. 4). While analyzing the existing process flow chart, used

at our SNCU triage, we found that maximum delay occurs during receiving

the baby, examining by the on duty doctors and execution of advice by

the nursing staff (Web Fig. 3). We found following

lacunae; there was no assigned doctor and nurse in triage area, no

measurement of time by using stopwatch, no separate emergency tray in

triage, lack of urgency, no written policy, and lack of positive

attitude.

The aim of the study thus was to initiate early

(within 30 min) emergency management of sick neonates at triage of SNCU

from baseline 20% to at least 80% over a period of eight weeks of

baseline and implementation phase (February-March, 2017).

Implementation phase: We tested change ideas,

studied and acted upon these change ideas to achieve our aim. Three

Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles, each for ten days, were conducted in

morning shift (8 AM to 2 PM). During PDSA 1, doctors and nurses of

morning shift were assigned by preparing a separate triage roster and

designated them by using triage sticker. Throughout PDSA 2, we arranged

a separate emergency tray in triage by using check list. During PDSA 3,

we arranged training of doctors and nurses about POCQI module and

emergency triage assessment and treatment (ETAT); and displayed the

treatment protocol in triage [6-9]. During the implementation phase, a

corrected process flow chart was used (Web Fig. 5).

Balancing measure was overcrowding at triage area. Frequent feedback

with run charts of percentage of babies receiving emergency treatment

within 30 minutes and appraisal in weekly meetings were done to motivate

stakeholders and encourage compliance.

Post-intervention phase: Between April and June

2017, the QI team encouraged the implementation of the change ideas of

early initiation of emergency management, continued to monitor the

percentage of sick neonates receiving treatment within 30 minutes with

run chart and provided feedback to the treating residents and nursing

staffs. To identify opportunities for process improvement, the QI team

continued to meet with clinical teams weekly, audited cases of delayed

management and addressed logistic issues related to supplies and

equipment.

Pertinent maternal and neonatal data were documented

in case record forms. The time gap between the arrival of a sick neonate

in the triage and initiation of treatment was noted using a stop watch.

The primary outcome was percentage of sick babies getting emergency

early management at SNCU triage. Secondary outcomes were hospital

mortality, requirement of mechanical and non-invasive respiratory

support and requirement of ionotropic support.

Statistical analysis: Statistical analysis

was done by using SPSS for Windows version 16 software (SPSS Inc.,

Chicago, Illinois). Between groups, data for continuous variables were

evaluated using a t test for independent variables. Comparisons

of proportions were made using Chi-square testing.

Results

Among total 390 sick neonates, 356 were enrolled (56

in baseline phase, 88 in implementation phase and 212 in post

intervention phase) in this study (Web Fig. 1).

Demographic characteristics were comparable among baseline and post

intervention cohorts (Table I).

TABLE I Demographic Characteristics of Neonates Enrolled in the Study

|

Characteristics |

Baseline |

Implemen- |

Post inter- |

|

(n=56) |

tation Phase |

vention Phase |

|

|

(n=88) |

(n=212) |

|

Maternal characteristics |

|

*Maternal age, y |

28 (3) |

27 (5) |

28 (4) |

|

Preterm delivery |

18 (33.3) |

35 (39.7) |

98 (46.2) |

|

#Risk factors |

0 |

5 (5.7) |

13 (6.1) |

|

Maternal hypertension |

12 (22.2) |

14 (16) |

26 (12.3) |

|

Maternal diabetes |

6 (11) |

7 (8) |

19 (9) |

|

Vaginal delivery |

37 (66.6) |

52 (59) |

125 (59) |

|

Neonatal characteristics |

|

#Gestational age (wk) |

36 (1.3) |

37 (1.2) |

36 (1.6) |

|

#Birthweight (g) |

2312 (180) |

2380 (208) |

2346 (160) |

|

Male gender |

31 (55.5) |

56 (63.6) |

137 (64.6) |

|

AGA |

43 (77.7) |

53 (60.2) |

155 (73.7) |

|

SGA |

12 (22.2) |

33 (37.5) |

52 (24.5) |

|

LGA |

1 (0.1) |

2 (2.3%) |

5 (2.4) |

|

Significant hypothermia |

24 (44.4) |

17 (19.3) |

84 (40.7) |

|

Apnea/gasping |

18 (33.3) |

56 (63.6) |

82 (39) |

|

Severe respiratory distress |

20 (36) |

33 (37.5) |

87 (41) |

|

Central cyanosis |

5 (0.08) |

4 (4) |

59 (2.8) |

|

Shock |

12 (22.2) |

47 (53.4) |

88 (41.5) |

|

Convulsions/coma/encephalopathy |

18 (33.3) |

58 (66) |

80 (38.5) |

|

Data expressed in n(%); *mean (SD) and #median (IQR); AGA

(appropriate for gestational age); SGA (small for gestational

age); LGA (large for gestational age); #Risk factors for early

onset sepsis include: very low birth weight (<1500 g),

prematurity, prolonged rupture of membranes(>24 h), foul

smelling liquor, multiple (>3) per vaginum examinations in 24 h,

intrapartum maternal fever (>37.8ºC). |

|

|

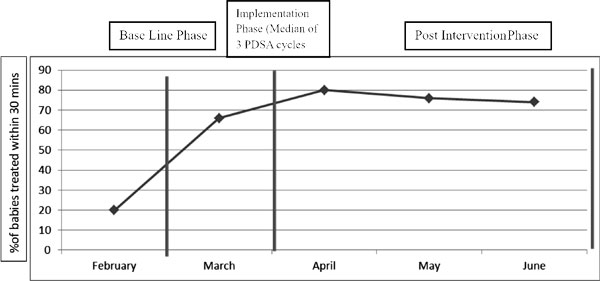

Fig. 1 Percentage of neonates

treated within 30 minutes in baseline phase, implementation

phase and in the post intervention phase.

|

During implementation phase, we registered successful

early initiation of management among 47%, 69% and 80% of sick neonates

following PDSA 1, PDSA 2 and PDSA 3, respectively (Web

Fig. 6). Throughout the time of post implementation

phase, 80%,76% and 74% of sick neonates received early emergency

treatment during each month of April, May and June of 2017,

respectively. (Fig. 1). In comparison to baseline

phase, the percentage of neonates receiving treatment within 30 minutes

of arrival at triage increased from 20% to 76% (P<0.001) and the

mean time of initiation of treatment decreased from 80.8 (20.9) to 19.8

(5.6) minutes (P<0.001) during post-implementation phase (Fig.

1 and Table II). Hospital mortality (33 vs 15%,

P=0.004) and need for ventilator support (44 vs 18%, P<0.001)

were also significantly lower among post- intervention cohort in

comparison to baseline cohort (Fig. 1 and Table

II). There was substantial improvement in early emergency management

during evening and night shift (42% and 33%, respectively) without

implementing PDSA cycles (Web Fig. 7).

TABLE II Outcome of Sick Neonates Enrolled in Baseline and Post-intervention Phase

|

Characteristics |

Baseline phase |

Post-intervention |

Odds ratio/ Mean |

P value |

|

(n=56) |

phase (n=212) |

difference (95% CI) |

|

|

Neonates treated within 30 min |

11 (20) |

161 (76) |

12.91(6.21-26.81) |

<0.001 |

|

Time of initiation of treatment* |

80.8 (20.96) |

19.8 (5.6) |

-61.0 (-64.18 - -57.8) |

<0.001 |

|

Hospital mortality |

18 (33.3) |

32 (15) |

0.37 (0.19-0.73) |

0.004 |

|

Total hospital stay (d)# |

16 (10-24) |

12 (8-22) |

– |

– |

|

Need for ventilator support |

24 (44.4) |

38 (18) |

0.29 (0.15-0.54) |

<0.001 |

|

Duration of ventilator support (d)# |

4 (2-6) |

3 (2-5) |

– |

– |

|

Need for ionotropic support |

18 (33.3) |

35 (16.5) |

0.41 (0.21-0.81) |

0.01 |

|

Need for >1 ionotropes |

12 (22.2) |

29 (13.6) |

0.58 (0.27-1.22) |

0.15 |

|

Values in No. (%), #Median (interquartile range)

or *mean (SD). |

Discussion

This QI effort was a stepwise introduction of

measures to initiate emergency management of sick neonates within 30

minutes driven by PDSA cycles. We showed improvement in mean time of

initiation of treatment, without crowding in the triage area which was

our key balancing measure. The mean time decreased by 60 minutes and the

percentage of neonates received treatment within 30 minutes increased

from 20% to 80%. This improvement was sustained throughout the

post-intervention phase.

Han, et al. [4] conducted a nine-year

retrospective cohort study of 91 infants and children who presented to

local community hospitals with septic shock and required transport to

central referral centre. They showed that when community physicians had

implemented therapies that resulted in successful shock reversal (within

a median time of 75 minutes), almost all of the infants and children

presenting with septic shock survived. That each hour of delay in

resuscitation was associated with a 50% increased odds of mortality.

Rivers, et al. [5] showed that implementation of early

goal-directed therapies in the emergency department, improved survival

outcomes in adult septic shock significantly. Study by investigators in

London also found that avoidable delays and inappropriate management

contributed to poor outcome among children with severe meningococcal

disease [10].

Booy, et al. [11] described a remarkable

improvement in outcome of meningococcal disease by dissemination of

recommended guidelines for managing meningococcal disease to area

community hospitals through educational outreach programs, facilitation

of early communication and management recommendations between the local

and referral hospital, and utilization of a mobile pediatric critical

care transport team. By implementing these change ideas there was an

impressive reduction of mortality from meningococcal disease in Southern

England from 23% to 2% in a span of just 6 years [11].

In our study, we implemented some simple measures in

a stepwise manner through PDSA cycles as per POCQI module [7]. Each PDSA

cycle helped us to test small interventions leading to valuable learning

and refinement of neonatal emergency management. Moreover, clinical team

was motivated with prominent display of run charts which served as an

instant display of outcome. This enabled team ownership, enthusiasm,

participation and an opportunity to improve. The percentage of babies

receiving early emergency management were increased remarkably in

evening and night shifts, though we did not assign any dedicated doctor

and nursing staff for triage in these shifts. Secondary outcomes like

in-hospital mortality, need for mechanical ventilation, and need for

ionotropic support also decreased significantly.

Our study has several limitations. Firstly, being a

single-center study, all the interventions implemented by us may not be

generalizable to other settings. Moreover due to lack of human resources

we were not able to assign nursing staff and doctors separately for

triage in evening and night shift. Secondary outcomes like mortality is

affected by a numerous factors other than delay in initiation of

treatment, we did not study those factors. Hence, to further establish

our study findings, further research is necessary with large sample size

incorporating all factors.

We decided to share our study findings with

appropriate authorities to motivate them and to ensure further logistic

support and human resources to implement these change ideas in other

shifts and health delivery facilities. Stepwise successful

implementation of PDSA cycles significantly increased the percentages of

sick newborns received early emergency management at SNCU triage and

thereby resulting in better survival among them. However, larger trial

over longer duration with continued surveillance is required to confirm

this fact.

Acknowledgement: D. TKS Mahapatra, NRS Medical

College, Kolkata; Dr VK. Paul, Member NITI Aayog, Government of India; Dr

Ashok Deorari, AIIMS, New Delhi and his team; and

Dr Deepak Chawla, Government Medical College and Hospital, Chandigarh

for their logistic support to complete this project successfully.

Contributors: AM and MB contributed equally to

this study. AM: study design and execution, preparation of manuscript

and critical review; MB, BM, SM, BA: study design and execution, data

collection and analysis, preparation of manuscript; BB: data analysis,

preparation of manuscript and critical review. All authors agreed and

approved the final version and vouch for the accuracy of the submitted

manuscript.

Funding: None; Competing interest:

None stated.

|

What is Already Known?

• Early initiation of emergency management at

triage reduces complications and mortality among sick neonates.

What This Study Adds?

• A quality improvement initiative focusing

on stepwise successful implementation of PDSA cycles

significantly increased the number of sick newborns receiving

early emergency management at SNCU triage, thereby resulting in

better survival.

|

References

1. West Bengal- WB Health.Vital Statistics. Available

from: https://www.wbhealth.gov.in/other_files/Health%20on%

20the%20March,%202015-2016.pdf Accessed February 24, 2018.

2. INAP-WHO Newborn CC. Available from:

https://www.newbornwhocc.org/INAP_Final.pdf. Accessed February 23,

2018.

3. Neonatal Health – Unicef India. Available from:

http:unicef.in/Whatwedo/2/Neonatal-Health. Accessed February 24,

2018.

4. Han YY, Carcillo JA, Dragotta MA, Bills DM, Watson

RS, Westerman ME, et al. Early reversal of pediatric-neonatal

septic shock by community physicians is associated with improved

outcome. Pediatrics. 2003;112:793-9.

5. Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, Ressler J, Muzzin

A, Knoblich B, et al. Early goal-directed therapy in the

treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J

Med. 2001;345:1368-77.

6. Family Health Bureau, Ministry of Health, Sri

Lanka. National Guidelines for Newborn Care. Volume iii. Available from:

http://fhb.health.gov.lk/web/index.php? optio=co_phocadownload&view=category&

download=

674:national-guidelines-for-newborncare-volume-111-pdf&id=10:intranatal-newborn-care&lang=en.

Accessed February 19, 2018.

7. POCQI –Learner Manual - WHO newborn CC. Available

from: https://www.newbornwhocc.org/POCQI-Learner-Manual.pdf..

Accessed February 19, 2018.

8. Clinical Protocols 2014- WHO newborn CC. Available

from: http://www.newbornwhocc.org/clinical_proto.html. Accessed

February 19, 2018.

9. National Neonatology Forum. NNF Guidelines 2011.

Clinical Practice Guidelines. New Delhi: National National Forum;

October, 2010.

10. Nadel S, Britto J, Booy R, Maconochie I, Habibi

P, Levin M. Avoidable deficiencies in the delivery of health care to

children with meningococcal disease. J Accid Emerg Med. 1998;15:298-03.

11. Booy R, Habibi P, Nadel S, de Munter C, Britto

J, Morrison A, et al. Reduction in case fatality rate from

meningococcal disease associated with improved healthcare delivery. Arch

Dis Child. 2001;85:386-90.

|

|

|

|

|