|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2018;55:757-760 |

|

Improving the

Breastfeeding Practices in Healthy Neonates During Hospital Stay

Using Quality Improvement Methodology

|

|

Seema Sharma1,

Chanderdeep Sharma2

and Dinesh Kumar3

From 1Departments of Pediatrics, 2Obstetrics

and Gynaecology and 3Community Medicine, Dr Rajendra Prasad

Govt. Medical College, Himachal Pradesh, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Seema Sharma, House no 23,

Block-B,Type-V, DR RPGMCH, Kangra at Tanda,

Himachal Pradesh, India.

Email: dr.seema73.ss@gmail.com

Received: September 26, 2017;

Initial review: November 15, 2017;

Accepted: May 16, 2018.

|

Objective: To demonstrate the applications of the

principles of Quality Improvement (QI) in a tertiary-care centre

with the aim to improve the breastfeeding practices during hospital

stay.

Methods: An operational team was formulated to

identify the reasons for low proportion of exclusive breast feeding

(EBF) in healthy neonates. Reason specific solutions were proposed,

discussed, prioritized and tested using Plan-Do-Study-Act Cycle (PDSA

Cycle). Strategies included clear departmental policy plan and creation

of Breastfeeding support package (BFSP). PDSA cycles were tested and

implemented over 6 weeks period and its sustainability was measured

monthly for five months duration.

Results: After implementation of PDSA cycles,

the proportion of neonates receiving early breastfeeding within one

hour of birth increased from 55% to 95%, and the proportion of neonates

on EBF during hospital stay increased from 72% to 98%.

Conclusion: Quality Improvement principles are

feasible and effective to improve breastfeeding practices in the

hospital setting.

Keywords: Breastmilk, Baby friendly hospital, Exclusive

breastfeeding, Intervention.

|

|

Breastmilk is safe, available, affordable and one

of the most effective ways to ensure child health in developing

countries [1,2]. According to UNICEF, only 39 % of infants 0-5 month-old

in the developing world are exclusively breastfed (EBF). About 1.45

million lives are lost due to suboptimal/breastfeeding in developing

countries per year [3,4] . NFHS 4 data for 15 states from India shows

rise in institutional deliveries to 82.2%, with initiation of early

breastfeeding stagnant at 47.7%, and EBF values of 40% for the first six

months of life. This study aimed to improve the breastfeeding practices

during hospital stay, as hospital-based practices affect the duration

and exclusivity of breastfeeding throughout the first year of life. The

two main objectives were to increase the proportion of neonates

receiving early BF within one hour of birth from 55% to 90% and neonates

on EBF at the time of discharge from the hospital from 72% to 90%, over

a period of six months using principles of Quality improvement.

Methods

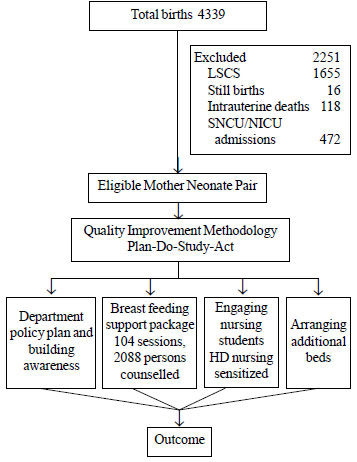

Mother-newborn pairs who were healthy and delivered

vaginally were included. Newborns delivered by lower segment caesarean

section, critically sick neonates, preterm neonates not on

breastfeeding/expressed breast milk, neonates of retro-positive mothers

who declined breastfeeding, and neonates having major congenital

malformations requiring surgical intervention were excluded (Fig.

1).

|

|

Fig. 1 Study flow chart.

|

A team consisting of faculty members from departments

of Pediatrics, Obstetrics and Community Medicine; health educator; a

nutritional counselor; the sister in-charge of the labor room, and a

staff nurse from postnatal ward was constituted to evaluate the reasons

for Non-exclusive breastfeeding (NEBF) and to plan the strategy for the

promotion of optional breastfeeding practices. A baseline survey was

conducted by the Nutritional counselor for three days/week from 10:00 to

12:00 Hr and 14:00 to 16:00 Hr every day in December 2016, to know the

prevailing breastfeeding practices. It highlighted poor adherence to

standard guidelines, inappropriate provision and promotion of infant

formula. Focussed Group discussions (FGDs) were followed by fish bone

analysis, which revealed that the reasons for NEBF were related to

policy, people, place and processes. Lack of knowledge, sensitization of

health care providers and lack of support for the mothers were few of

the vital reasons limiting the BFP (Web Fig. 1).

Suggested solutions were prioritized and each

proposed solution was considered as a change idea and was tested on five

mothers for one day in order to adopt or adapt the proposed solution.

There were four change ideas which were applied weekly for the period of

six weeks. The data was collected after each Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA)

cycle for 3 days/week for six weeks initially to see the feasibility. To

assess the sustainability of the Quality-improvement (QI) practices,

subsequent data collection was done monthly for a period of five months

in a manner similar to the baseline assessment. The team met weekly for

six weeks, followed by monthly meetings for five months. The change

ideas were implemented as PDSA Cycles in accordance with QI principles.

PDSA Cycle I: Department policy plan and building

awareness amongst health care providers: A policy plan regarding

breastfeeding practices was circulated amongst all health care providers

with the emphasis on not prescribing formula feed unless clinically

indicated. To create awareness in healthcare providers, FGDs with

residents, in-charge sisters and nursing sister of labor room and sick

newborn care unit (SNCU) were carried out. A poster was displayed in the

labor room for dissemination of the information.

PDSA II: Breastfeeding support package:

The data showed that merely building awareness and making policy clear,

changes the pattern of breastfeeding practices; through, some resistance

from the mothers and their attendants was observed. During third week,

team came up with the idea of delivering a BFSP, the components are

depicted in Box I.

|

Box I Components of Breastfeeding

Support Package

• Counselling of the mothers and attendants

in the group of 15-20, on breastfeeding practices and its

benefits, in the labor room and postnatal ward using IYCF

(Infant and young child feeding) guidelines.

• One ear-marked SNCU nursing sister to be

posted in each shift in the labor room - NBCC (Newborn Care

Corner) to ensure early initiation of breast feeding.

• Additional support was provided by the

nursing staff in the postnatal ward to provide practical help to

the mothers.

|

PDSA III: Engaging nursing students: To deliver

BFSP to each and every mother, team decided to engage nursing students

present in all the shifts in the labor room and postnatal ward. Nursing

students were sensitized under the supervision of health educator and

counselor. Finally, nursing students started providing BFSP throughout

their posting.

PDSA IV: Arranging additional beds: Although data

started showing improvement in the BFP, team realized that mothers are

shifted soon after delivery from labor room to postnatal ward, which was

making early initiation of BF difficult. Hence, to provide bedding-in

facility, the team arranged additional 10 beds for mothers outside the

labor room in the fourth week. The additional benefits were prolonged

observation of mothers for any complications after delivery and their

counselling on nutrition and family planning which was missed earlier.

The team members shared the results of interventions

and gave continuous feedback to staff and resident doctors involved in

clinical care.

Results

In the baseline survey, out of total 280 healthy

neonates, 154 (55%) had received early breastfeeding. Out of remaining

126 (45%), 78 (28%) had received non-breast milk supplements and 48

(17%) received nothing. During hospital stay, 78 (28%) of the healthy

neonates were not on EBF. These neonates were receiving either infant

formula feed or mixed feeds (breastfeeding along with formula feed).

Amongst total 280 mothers, 154 (55%) were primigravida. About one third

of multiparous mothers had unsatisfactory experience of breastfeeding

due to poor positioning and poor attachment.

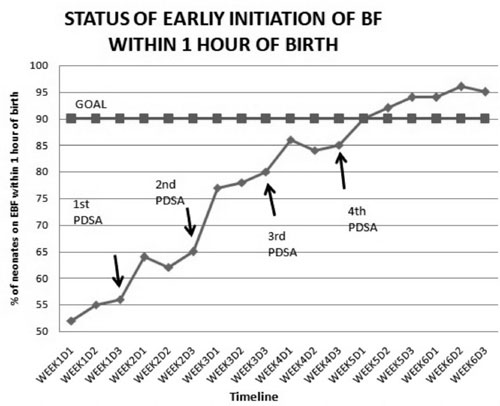

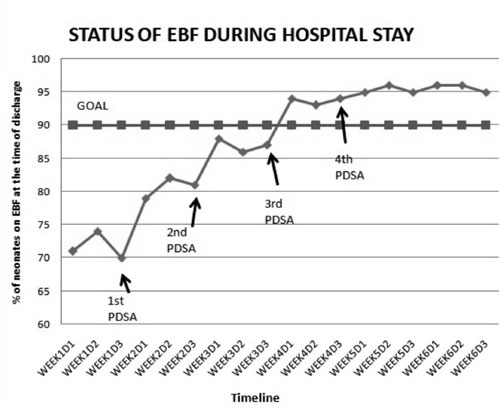

After four PDSA cycles, the proportion of neonates

receiving early breastfeeding within one hour of birth increased from

55% to 95% and the proportion of neonates on EBF during hospital stay

increased from 72% to 98% (Fig. 2 a and b).

|

| (a) |

|

| (b) |

|

Fig. 2 (a) Status of early initiation

of breastfeeding within one hour of birth; (b) Status of

exclusive breastfeeding during hospital stay.

|

The assessment for sustainability for five months

revealed that trend of improved BFP remained above 95%. To ensure smooth

running of system, healthcare providers were oriented on optional

breastfeeding practices at the time of their joining.

Discussion

Low- and middle-income countries lose more than $70

billion annually due to low rates of breastfeeding. Universalization of

breastfeeding in India may reduce 1,56,000 under-5 deaths, 39,00,000

episodes of diarrhea, 34,36,560 episodes of pneumonia and 7,000 deaths

due to breast cancer annually [1,2]. Our root cause analysis showed

widespread use of NEBF to be due to poor antenatal care, and lack of

information on optimal infant feeding, especially EBF, given by health

workers at health institutions. This study revealed that lack of early

initiation of BF, lack of bedding-in facility and not giving EBF during

their last pregnancy was associated with NEBF. Inappropriate provision

and promotion of infant formula were common, despite evidence that such

practices reduce BF success. These findings are in accordance with the

available literature [5-7]. In our study, rates of early initiation of

BF and EBF increased significantly during hospital stay. It showed

sustainability of 95% even after 6 months of implementation. These

results show impact similar to the previous work done to improve EBF

rates using QI principles [8-12].

Our study showed processes and system changes

resulted into improvement in BFP. Important reductions in morbidity and

health care costs with a positive public impact are possible if our

method of QI is widely disseminated. A study on impact of optional

breastfeeding practices BFP during hospital stay on continuation of EBF

upto 6 months of age could have strengthened our study results.

The present study suggests that QI principles are

feasible and lead to improved rates of BFP during hospital stay. This is

a single centre QI initiative done with the involvement of existing

caregivers and executed without any external funding in the form of

manpower or financial assistance, which suggests the importance of

simple and feasible QI principles using team approach. Formation of a

breastfeeding support group is the next step to sustain these practices.

This QI initiative has helped our institute to improve breastfeeding

practices by transforming maternity practices to better support mothers

who choose to breastfeed. Such efforts, could affect both initiation and

duration of breastfeeding, with substantial, lasting benefits for

maternal and child health.

Acknowledgements: The authors acknowledge

the support of USAID Team consisting of Dr Nigel, Mr Praveen and Dr

Anjali for introducing them to the concept of quality improvement and

hand holding during this QI project.

Contributors: SS: has conceptualized the

concept; SS,CD,DK: were involved into collection of data and its

analysis. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding: None; Competing Interest: None

stated.

|

What This Study Adds?

• Quality Improvement principles are feasible and effective

to improve exclusive breast feeding practices in the

hospital-setting.

|

References

1. Essential Nutrition Actions: Improving Maternal,

Newborn, Infant and Young Child Health and Nutrition. Geneva: World

Health Organization; 2013. Available from:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK258736/. Accessed March 18,

2018.

2. Planning Guide for National Implementation of the

Global strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding. World Health

Organization; 2013. Available from:

https://www.int/nutrition/publications/infant feeding/9789241595193/en/.

Accessed March 18, 2018.

3. Breastfeeding: Impact on Child Survival and Global

Situation. New York: UNICEF; 2014. Available from:

https://www.unicef.org/nutrition/index_24824.html. Accessed March

18, 2018.

4. Lauer JA, Betran AP, Barros AJ, Md O. Deaths and

years of life lost due to suboptimal breastfeeding among children in the

developing world: A global ecological risk assessment. Public Health

Nutr. 2005;9:673-85.

5. Agho KE, Dibley MJ, Odiase JI, Ogbonmwan SM.

Determinants of exclusive breastfeeding in Nigeria. BMC Pregnancy

Childbirth. 2011;11:2.

6. Woldie TG, Kassa AW, Edris M. Assessment of

exclusive breastfeeding practice and associated factors in Mecha

District, North West Ethiopia. Sci J Public Health. 2014;2:330-6.

7. The State of the World’s Children. UNICEF, 2000.

Available from: www.unicef.org/sowc00/stat4htm. Accessed March

18, 2018.

8. Mercier CE, Barry SE, Paul K, Delaney TV, Horbar

JD, Richard C, et al. Improving newborn preventive services at

the birth hospitalization: A collaborative, hospital-based

quality-improvement project. Pediatrics. 2007;120:481-8.

9. Kuzma-O’Reilly B, Duenas ML, Greecher C, Kimberlin

L, Mujsce D, Walker DJ. Evaluation, development, and implementation of

potentially better practices in neonatal intensive care nutrition.

Pediatrics. 2003;111:e461-70.

10. Bloom BT, Mulligan J, Arnold C, Ellis S, Moffitt

S, Rivera A, et al. Improving growth of very low birth weight

infants in the first 28 days. Pediatrics. 2003;112:8-14.

11. Merewood A, Philipp BL, Chawla N, Cimo S. The

baby-friendly hospital initiative increases breastfeeding rates in a US

neonatal intensive care unit. J Hum Lactation. 2003;19:166-71.

12. Sethi A, Joshi M, Thukral A, Dalal JS, Deorari

AK. A quality improvement initiative: Improving exclusive breastfeeding

rates of preterm neonates. Indian J Pediatr. 2017;84:322-5.

|

|

|

|

|