|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2018;55: 739-743 |

|

Impact of Quality Improvement Program on

Expressed Breastmilk Usage in Very Low Birth Weight Infants

|

|

Anup Thakur 1,

Neelam Kler1,

Pankaj Garg1,

Anita Singh2 and

Priya Gandhi1

From 1Department of Neonatology, Institute

of Child health, Sir Ganga Ram Hospital, Rajinder Nagar, New Delhi; and

2Department of Neonatology, Sanjay Gandhi Postgraduate

Institute of Medical Sciences, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Anup Thakur, Consultant

Neonatologist, Institute of Child health,

Sir Ganga Ram Hospital, New Delhi, India.

Email: [email protected]

Received: January 27, 2017;

Initial review: May 29, 2017;

Accepted: July 12, 2018.

|

|

Objective: To improve the usage

of expressed breast milk in very low birth weight infants admitted in

the neonatal intensive care unit of a tertiary centre in India.

Methods: Between April 2015 and

August 2016, various Plan-do-act-study cycles were conducted to test

change ideas like antenatal counselling including help of brochure and

video, post-natal telephonic reminders within 4-6 hours of birth,

standardization of Kangaroo mother care, and non-nutritive sucking

protocol. Data was analyzed using statistical process control charts.

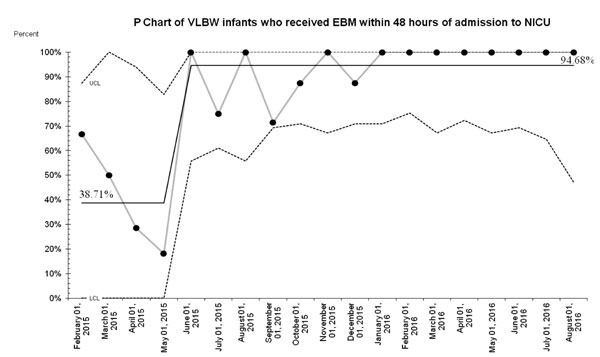

Results: 156 very low birth

weight infants were delivered during the study period, of which 31 were

excluded due to various reasons. Within 6 months of implementation, the

proportion of very low birth weight infants who received expressed

breast milk within 48 hours improved to 100% from 38.7% and this was

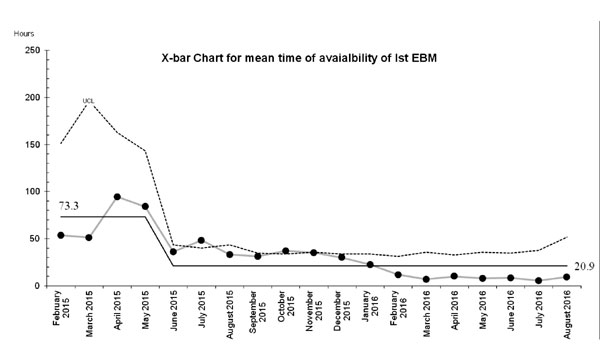

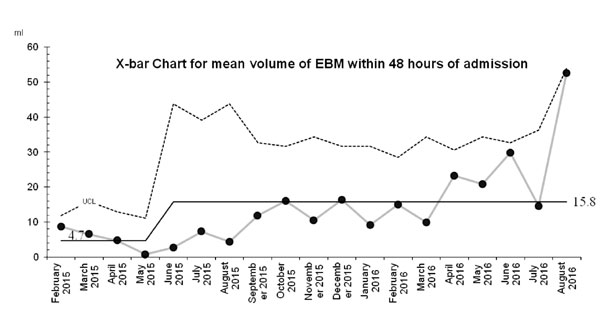

sustained at 100% for next 8 months. The mean time of availability and

volume of expressed breast milk within 48 hours, improved gradually from

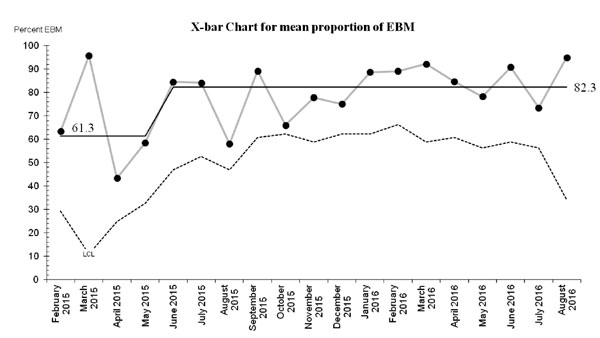

73.3 h to 20.9 h and 4.7 mL to 15.8 mL, respectively. The mean

proportion of expressed breast milk once infant reached a feed volume of

100 mL/kg/day also improved from 61.3% to 82.3%.

Conclusion: Quality improvement

interventions showed promising results of increased expressed breast

milk usage in very low birth weight infants.

Keywords: Antenatal counselling,

Breastfeeding, Care bundle, PDSA cycle.

|

|

H

uman milk has immunerable benefits for infants,

especially very low birth weight (VLBW) infants [1]. Recent evidence

implicate that prematurity related morbidities are closely related to

specific critical periods following birth, during which the use of human

milk may be most important. In addition, the dose and exposure period of

human milk appears critical to confer its benefits [2]. Four

well-controlled studies in premature infants have linked the dose of

human milk (mL/kg/d) received throughout the Neonatal Intensive Care

Unit (NICU) stay with specific health outcomes during or after NICU stay

[3-6]. However, the usage of human milk in VLBW infants varies globally

and human milk banks are not widely available, especially in resource

limited settings. In such a scenario when donor human milk feeding is

not available, the only feasible option available to clinicians for

optimum nutrition of preterm infants is to make mothers own milk

available. Quality improvement (QI) programs through altered clinical

behavior and by delivering consistent good practice can improve usage of

human milk and therefore improve health outcomes of preterm infants [7].

Interventions such as antenatal consults, lactation counselling,

tracking motherís milk supply, staff education, and other evidence-based

bundles have been used to improve usage of human milk [8-13]. However,

no QI initiatives have been reported from India focussing on EBM usage

in VLBW infants.

In our unit, the usage of expressed breast milk (EBM)

in VLBW infants was low, and the proportion of EBM usage of total feeds

was only 52% [14], and the availability of first EBM after birth was

often delayed for days. This prompted us to start a QI program in our

hospital in collaboration with Institute of Healthcare Improvement

(IHI), Massachusetts and ACCESS health International, India with an

objective to improve usage of EBM in VLBW infants. The specific goals of

the project were to obtain EBM in >80% of VLBW infants within 48 hours

of admission to the NICU, improve volume of EBM obtained in first 48

hours (by 100%), to decrease the time of availability of first EBM by

20% of baseline and to improve proportion of EBM volume usage by more

than 20% of baseline.

Methods

The project was carried out in a tertiary-care center

with level III B NICU in India from April 2015 to August 2016. The

institute does not have a human milk bank and enteral feeding depends on

availability of motherís own milk; in case of unavailability of motherís

own milk, preterm formula is used. This project involved the systematic

implementation of evidence-based practices utilizing QI strategies and

thus did not require Institutional Review Board approval.

Data on all inborn infants with a birth weight of

£1500 g

admitted to the NICU were included. Driver diagram (Web Fig. 1)

was developed after internal discussions. The nature of intervention was

chalked out by a multi-disciplinary QI team. It consisted of two

consultant neonatologists, two neonatology residents, a dedicated

lactation counsellor, nurse in charge of NICU and delivery room, four

senior NICU nurse with extensive feeding expertise, two improvement

experts, and one project manager. This team underwent extensive

brainstorming sessions and performed the root cause analysis of less

usage of EBM in NICU (Web Fig. 2.). The QI team then

developed the Care bundles based on evidence based practices distilled

from literature search, and agreed upon or modified them for local

implementation. A summary of the components of the care bundle is

provided in Web Table I. The care bundle consisted of two

elements: promotion of early milk expression and ongoing support for

lactation and stress management.

In the first phase of the project, from April to June

2015, change ideas were tested by repeated PDSA cycles. Change ideas

were modified or discarded based on PDSA ramps. In the first PDSA ramp (Web

Fig. 3), the change idea of antenatal counselling was developed

and tested. Initially antenatal counselling was done in two cases at

random and EBM was not available in the first 48 hours in either of

them. This idea was discarded. In the second cycle, we developed and

tested a standardized format for antenatal counselling in three cases

and EBM within 48 hours was available in two of these. The mother who

failed to send EBM to the NICU gave the feedback that she forgot about

sending EBM. In the third cycle, we added the change idea of giving

telephonic reminders to the mother within 6 hours of delivery. We tested

these in another four cases and could get EBM within the stipulated time

in all cases. In the second phase from mid-June 2015, implementation of

these tested change ideas was started while ongoing PDSA were being

conducted. The QI team received a feedback from the mothers that a

pictorial illustration would help them better to pump EBM, so a brochure

and posters were developed and tested in the fourth cycle in July

2015.In the fifth cycle, we added on the change idea of showing videos

to mothers during antenatal counselling sessions. The completed PDSA

ramp 1 was implemented in August 2015. Similar to PDSA ramp 1, PDSA ramp

2 constituted of three consecutive PDSA cycles of developing and testing

a standardized KMC and NNS protocol followed by its implementation in

late August 2015. PDSA ramp 3 constituted of three consecutive PDSA

cycles in August to develop and test list-based tracking of mothers.

PDSA ramp 4 consisted of another three cycles of daily data entry of EBM

status in weight book by nurses, integration of data in excel sheet by

residents, followed by Excel-based daily counselling by consultants

before it was implemented in September 2015. PDSA ramp 5 consisted of

two PDSA cycles on change idea of fortnightly video-based group

counselling sessions of mothers in the NICU. PDSA ramp 6 was run in

December 2015 and in a planned experimentation design, change ideas of

daily team huddle, text messaging and admission brochure were tested.

The improvement activities are described in

Web

Box 1.

Process and Outcome Measures: The process

measures studied monthly were proportion of mothers counselled ante-natally

or post-natally for expression of breast milk and proportion of eligible

VLBW infants who received Kangaroo mother care and non-nutritive

sucking. The outcomes measures that were evaluated monthly for infants

born £1500 g

birth weight were percentage of infants who received EBM within first 48

hours of birth, time of availability of first EBM, volume of EBM

available in first 48 hours, and volume of EBM vs formula (in %)

once infant reached a feed volume of 100 mL/kg/day. The balancing

measure was proportion of normal term infants discharged on total breast

feeds.

Baseline data of each eligible infant from February

2015 to April 2015 was collected retrospectively from infantís daily

milk record. Following April 2015, after initiation of IA program all

data was collected prospectively.

Data analysis: Data were analyzed using QI

charts software. Statistical process control charts called Shewhartís

charts were used in our project to evaluate the effectiveness of

intervention over time [15-17]. The control limits on the charts (upper

and lower) establish the margins within which the measurement will be

found approximately 99% of the time. The observed change was considered

significant i.e. resulting from a special cause variation as per

rules for special cause [18]. P statistical process chart was used to

examine non-nutritive sucking, Kangaroo mother care, antenatal

counseling and percentage of VLBW infants who received EBM within first

48 hours of birth. X-bar chart was used to examine time of availability

of first EBM, volume of EBM available in first 48 hours and proportion

of EBM once infants reached a feed volume of at least 100 mL/kg/day.

Results

A total of 156 VLBW infants were delivered during the

study period, of which 31 were excluded from analysis as their mothers

required admission in ICU due to one of the postnatal complications like

seizure, shock or severe post-partum bleeding. One hundred and twenty

five eligible VLBW infants were finally included for analysis. The mean

(SD) gestational age and birth weights of the infants were 29.6 (2.6)

weeks and 1094 (243) g, respectively.

The proportion of mothers counselled ante-natally or

post-natally for expression of breast milk improved over time and was

sustained. The proportion of eligible infants who received Kangaroo

mother care and non-nutritive sucking remained above 90% in 12

consecutive data points (Web Fig. 4). Before

implementation of any component of care bundle, the proportion of VLBW

infants who received EBM within 48 hours of birth was 38.7%. Within 6

months of implementation, this improved to 100% and following the most

recent interventions, this was sustained at 100% for next 8 months (Fig.

1a). The mean time of availability and mean volume of EBM within 48

h, before the implementation phase was 73.3 h and 4.7 mL, respectively.

After this phase, the mean time of availability of first EBM steadily

declined to 20.9 h and mean volume of EBM obtained within 48 h of birth

improved more than three folds to 15.8 mL (Fig. 1b, 2a).

The mean proportion of EBM once infant reached a feed volume of 100 mL/kg/day

also improved from 61.3% to 82.3% (Fig. 2b). The balancing

measure-proportion of normal term infants discharged on total

breastfeeds did not show any significant change during the project.

|

| (a) |

|

| (b) |

|

Fig. 1 (a) P chart of VLBW

infants who received EBM within 48 hours of admission to NICU;

and (b) X-bar chart for mean time of availability of first

expressed breast milk (EBM).

|

|

| (a) |

|

| (b) |

|

Arrows denote points of implementation of

change ideas; June 2015-Antenatal counselling, reminders,

physical help by lactation counsellor; August 2015- KMC/NNS,

brochure/videos/postnatal daily counselling and list based

tracking; September 2015-excel sheet based daily counselling;

October 2015-video based counselling; December 2015-planned

experimentation including team huddle.

Fig. 2 (a) X-bar Charts for mean volume of

first expressed breast milk (EBM) within 48 hours of admission and

mean proportion of expressed breast milk (EBM).

|

Discussion

This quality improvement initiative resulted in

increase in proportion of VLBW infants who received EBM within first 48

hours of birth, decreased time of availability of first EBM, increased

volume of available EBM in first 48 hours and overall higher consumption

of EBM in VLBW infants.

Our results are consistent with other studies that

had used similar or different care bundles for achieving higher human

milk consumption in VLBW infants [8-13]. Sisk, et al. [8] in a

study evaluated the impact of lactation counselling on initiation of

milk expression and found that counselling mothers of VLBW infants

increases the incidence of lactation initiation and breastmilk feeding

without increasing maternal stress and anxiety. Murphy, et al.

[9] implemented similar interventions in addition to tracking of

motherís milk supply and physician education. The median time of first

maternal milk expression decreased significantly and there was

significant improvement in the proportion of infants receiving exclusive

motherís breast milk at 28 days and at discharge. Spatz, in 2004,

recommended 10 steps for promoting and protecting breastfeeding in

vulnerable infants [18-19].The steps involved various aspects of

lactation support including assisting the mother with the establishment

and maintenance of a milk supply, providing skin-to-skin care (Kangaroo

care) and opportunities for non-nutritive sucking at the breast, and

providing appropriate follow-up care. Fugate, et al. [20]

implemented the ten steps in a continuous quality improvement initiative

and achieved significant improvements in the percentages of mothers

expressing their milk within 6 hours of delivery, infants receiving

motherís own milk at initiation of feeds, and mothers with a

hospital-grade pump at discharge. The findings of QI initiative that we

conducted are similar to above published literature.

The care bundles that were used in our QI initiative

were tailor-made for our system and upscaled through multiple PDSA

cycles before implementation. The use of planned experimentations in

choosing some of the care bundles to improve EBM usage is unique to this

QI initiative. The outcome measure that improved quickly after

implementation was time of availability of first EBM. This happened

because the enthusiastic team members would initiate pumping mothersí

milk themselves as soon as motherís condition permitted. A dedicated

NICU lactation consultant and the NICU nursing team were key members of

the team. However, the volume of EBM and proportion of EBM of total

feeds not only depended on team memberís efforts but also on the

commitment of the mothers and physical as well as emotional state. When

the time of availability of first EBM consistently came down, we then

focussed on outcome measures of improving volume of EBM.

The strength of this QI project is that it represents

one of the first few published reports from India to demonstrate the

effectiveness of the systematic implementation of QI methods to improve

usage of human milk in very low birth weight infants. We used a

dedicated lactation consultant to lead the QI improvement project.

Nonclinical duties were therefore delegated to ancillary personnel. The

improvement project has some limitations. First, the care bundles that

were tested in various PDSA cycles were implemented in groups rather

than as individual interventions. This potentially limits our ability to

link the interventions with the outcome. This also led us to describe

our results in two phases. Phase 1 was the initial phase of the project

which had some PDSA testing going on, while phase 2 had both

implementation and testing going on con-currently. In our project, as no

baseline data was available, historical data was used to create baseline

along with first few data points while the project was getting up and

running. This is crude but can be useful as chances are that the

processes have not been improved much during this start up time frame.

Secondly, the outcomes of our study could have been possibly confounded

due to constant supervision and monthly reporting of data to IHI from

April 2015 to March 2016 but the fact that the results of the study were

sustained even after this phase, possibly mitigates this bias. Thirdly,

our study was conducted in a level 3B NICU and the study sample was well

educated so counselling and implementation of other change ideas could

be easier than would be expected in a different set-up. So, some

interventions may need to be modified as per the population and local

set-up. In addition, although no additional manpower was employed for

this QI Project nor was it funded but a replication of similar results

may require a dedicated QI team that takes up additional responsibility

without compromising other aspects of clinical care unless the entire

process is integrated in the system and becomes a culture of the unit.

We conclude that by systematic application of QI

methods EBM usage of motherís own milk in VLBW infants can be

significantly improved and sustained. Further research should focus on

replicating these findings in different settings, further expanding the

benefits to all neonates admitted in NICU who require EBM and evaluating

the impact of increased EBM, usage on clinical outcomes such as sepsis,

necrotizing enterocolitis, mortality and long term neurodevelopment.

Acknowledgements: Institute of Healthcare

Improvement (IHI), Massachusetts and ACCESS health International, India

for providing training, supervision and feedback during the project.

Contributors: AT, NK: conceptualized the

project; AT: developed the protocol; AT, PRG: had primary responsibility

of patient screening, enrolment and data collection; AT: performed the

data analysis; AT: wrote the manuscript; NK, PG: participated in

protocol development, supervising enrolment, outcome assessment and in

writing the manuscript; AS: participated in planning of project and

writing of manuscript.

Funding: None; Competing interests: None

stated.

|

What This Study Adds?

ē QI program can be implemented and sustained

even in resource-limited settings to improve usage of human milk

in very low birth weight infants.

|

References

1. Henderson G, Anthony MY, McGuire W. Formula milk

versus maternal breast milk for feeding preterm or low birth weight

infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;17:CD002972.

2. Meier PP, Engstrom JL, Patel AL, Jegier BJ, Bruns

NE. Improving the use of human milk during and after the NICU stay. Clin

Perinatol. 2010;37:217-45.

3. Schanler RJ, Lau C, Hurst NM, Smith EOB.

Randomized trial of donor human milk versus preterm formula as

substitutes for mothersí own milk in the feeding of extremely premature

infants. Pediatrics. 2005;116:400-6.

4. Schanler RJ, Shulman RJ, Lau C. Feeding strategies

for premature infants: Beneficial outcomes of feeding fortified human

milk versus preterm formula. Pediatrics. 1999;103:1150-7.

5. Vohr BR, Poindexter BB, Dusick AM, McKinley LT,

Higgins RD, Langer JC, et al. Persistent beneficial effects of

breast milk ingested in the neonatal intensive care unit on

outcomes of extremely low birth weight infants at 30 months of

age. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e953-9.

6. Vohr BR, Poindexter BB, Dusick AM, McKinley LT,

Wright LL, Langer JC, et al. Beneficial effects of breast milk in

the neonatal intensive care unit on the developmental outcome of

extremely low birth weight infants at 18 months of age. Pediatrics.

2006;118:e115-23.

7. Battersby C, Santhakumaran S, Upton M, Radbone L,

Birch J, Modi N, et al. The impact of a regional care bundle on

maternal breast milk use in preterm infants: outcomes of the East of

England quality improvement programme. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed.

2014 ;99:F395-401.

8. Sisk PM, Lovelady CA, Dillard RG, Gruber KJ.

Lactation counseling for mothers of very low birth weight infants:

effect on maternal anxiety and infant intake of human milk. Pediatrics.

2006:117:e67-75.

9. Murphy L, Warner DD, Parks J, Whitt J, Peter-Wohl

S. A quality improvement project to improve the rate of early breast

milk expression in mothers of preterm infants. J Hum Lact.

2014;30:398-401.

10. Pineda RG, Foss J, Richards L, Pane CA.

Breastfeeding changes for VLBW infants in the NICU following staff

education. Neonatal Netw. 2009;28:311-9.

11. Ward L, Auer C, Smith C, Schoettker PJ, Pruett R,

Shah NY, et al. The human milk project: a quality improvement

initiative to increase human milk consumption in very low birth weight

infants. Breastfeed Med. 2012;7:234-40.

12. Meier PP, Engstrom JL, Mingolelli SS, Miracle DJ,

Kiesling S. The Rush Mothersí Milk Club: breastfeeding interventions for

mothers with very-low-birth-weight infants. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal

Nurs. 2004;33:164-74.

13. Verma A, Maria A, Pandey RM, Hans C, Verna M,

Sherwani F. Family-centered care of sick newborns. A randomized

controlled trial. Indian Pediatr. 2017;54:453-9.

14. Dogra S, Thakur A, Garg P, Kler N. Effect of

differential enteral protein on growth and neurodevelopment in

infants <1500 g: A randomized controlled trial. J Pediatr Gastroenterol

Nutr. 2017;64:e126-e32.

15. Amin SG. Control charts 101: A guide to health

care applications. Qual Manag Health Care. 2001;9:1-27.

16. Benneyan JC, Lloyd RC, Plsek PE. Statistical

process control as a tool for research and healthcare improvement. Qual

Saf Health Care. 2003;12:458-64.

17. Moen RD, Nolan TW, Provost LP. Improvement in

Quality In: Judy Bass, editor. Quality Improvement through

Planned Experimentation, 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2012.p.1-23.

18. Provost LP , Murray SK. Learning from Variation

in Data In: Jossey Bass, editors. The Healthy Care Data

Guide Learning from Data for Improvement,1st ed. San Francisco: Wiley

Inc; 2011.p.116-7.

19. Spatz DL. Ten steps for promoting and protecting

breastfeeding for vulnerable infants. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs.

2004;18:385-96.

20. Fugate K, Hernandez I, Ashmeade T, Miladinovic B,

Spatz DL. Improving human milk and breastfeeding practices in the NICU.

J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2015;44: 426-38.

|

|

|

|

|