|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2013;50:

847-852 |

|

Outcome of Very Low Birth Weight Infants with

Abnormal Antenatal Doppler Flow Patterns:

A Prospective Cohort Study

|

|

CVS Lakshmi, G Pramod, *K Geeta, S Subramaniam,

#Marepalli B Rao,

$Suhas G Kallapur, and S

Murki

From the Departments of Pediatrics and *Obstetrics and Gynecology,

Fernandez Hospital, Boggulkunta, Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh, India;

#Division of Biostatistics, Dept. of Environmental Health

University of Cincinnati, 3223, Eden Avenue, Cincinnati, Ohio 45267; USA

and $Divisions of Neonatology and Pulmonary Biology, Cincinnati

Children’s Hospital Medical Center, University of Cincinnati, 3333

Burnet Avenue, Cincinnati, Ohio 45229, USA.

Correspondence to: Dr Srinivas Murki, Consultant Neonatologist,

Fernandez Hospital, Boggulakunta, Hyderabad.

Email:

srinivas_murki2001@yahoo.com

Received: September 06, 2012;

Initial review: October 16, 2012;

Accepted: February 26, 2013.

PII:

S097475591200788

|

Background:

Fetal growth

restriction and abnormal Doppler flow studies are commonly associated.

Neonatal outcomes are not well known particularly in developing

countries, where the burden of the disease is the highest.

Objective: To determine outcomes of

preterm infants with history of absent/reversed end-diastolic umbilical

artery Doppler flow (AREDF) vs. infants with forward

end-diastolic flow (FEDF).

Design: Cohort study.

Setting: Tertiary care perinatal center in India.

Participants: 103 AREDF very low birth weight

(<1500 gm) (VLBW) infants and 117 FEDF VLBW infants were prospectively

enrolled.

Results: At 40 weeks adjusted post-menstrual age,

AREDF vs. FEDF group had a higher risk for death in the

NICU (12% vs. 1%), respiratory distress syndrome (33% vs.

19%), and cystic periventricular leukomalacia (12% vs. 1%). At 12-18

months corrected age, AREDF vs. FEDF group had a trend towards increased

risk for cerebral palsy (7% vs. 1%, P=0.06). After

logistic regression analysis, adjusting for confounders, AREDF was

independently associated only with mortality in the NICU.

Conclusion: AREDF is an independent predictor of

adverse outcomes in preterm infants in a developing country setting.

Keywords: India, Intrauterine growth restriction, Outcome,

Prognosis, Pre-eclampsia.

|

|

Intrauterine growth restriction can be caused by a

number of conditions but pregnancy induced hypertension and vascular

disorders of the placenta are among the most common etiologies

responsible for about 25-30% of IUGR [1]. Although the incidence of IUGR

is about 8% in the Western world [2], the prevalence in the developing

world is much higher at ~35% [3].

Although a number of different modalities are used

for fetal surveillance of IUGR, umbilical Doppler flow pattern is one of

the most widely used tests [4]. A number of observational studies have

reported outcomes in IUGR infants with abnormal antenatal Doppler flow

pattern [5-10]. However,

there are few studies [11,12] from the developing world, where the

global burden of the fetal growth restriction and preeclampsia is the

highest [3,13]. This information is essential to devise strategies for

reducing the rates of still-births/prematurity globally [14]. We

hypothesized that an absent or reversed end diastolic flow in umbilical

artery (AREDF) would be an independent predictor of adverse short-term

and long-term infant outcomes. We report the comparison of AREDF vs.

forward end-diastolic flow (FEDF) on comprehensive short-term outcomes

and long-term neurosensory and growth outcomes in preterm infants.

Methods

Parents of 238 very low birth weight (VLBW) infants

(<1500 gm birth weight) and gestation <35 weeks born consecutively

between the periods January 2007 to December 2008 at our referral

perinatal center were prospectively approached for informed consent for

enrolment at admission into the NICU. Infants with major congenital

malformations were excluded. Gestational age was determined by a first

trimester ultrasound scan, or by the mother’s last menstrual period.

Antenatal umbilical artery Doppler flows (Voluson, Philips and Logic Q

machines) were measured in pregnant women less than 35 weeks of

gestation and reported as forward, absent or reversal of flow during

diastole. The indications for Doppler studies were (a) evidence

of growth restriction on serial scans (based on Mediscan charts, Chennai

[15]), (b) pregnancy induced hypertension, and (c) history

of intrauterine death in a previous pregnancy. The umbilical artery

Doppler velocimetries reported in the study were those obtained closest

to delivery. The study population was divided into two cohorts viz.,

AREDF group comprising VLBW infants with absent or reversed

end-diastolic flow velocities in the umbilical artery; and FEDF group

with VLBW infants with forward Doppler flow velocity in umbilical artery

and those in whom antenatal Doppler studies were not indicated.

The primary outcomes included: Composite outcome of

death or major neuro-morbidity at 12-18 months of corrected age, defined

as presence of cerebral palsy or visual or hearing impairment. The

secondary outcomes included morbidities common in preterm infants. The

diagnosis of cerebral palsy was made by clinical examination by

experienced physicians blinded to the antenatal Doppler studies. Hearing

impairment was defined as any degree of hearing loss requiring the need

for hearing aids.

The antenatal details of study infants were collected

retrospectively from a computerized database and patient medical

records. All enrolled infants were followed up weekly/biweekly till they

were 40 weeks of corrected postmenstrual age, and then at 3,6,9,12 and

18 months of corrected age for growth and neurological assessment in the

high-risk neurodevelopmental follow-up clinic. At 40 weeks of corrected

postmenstrual age, each infant had a cranial ultrasound and a brain stem

evoked response audiometry. Growth was evaluated by measuring the

weight, head circumference and length by a trained nurse and plotted on

the Indian Academy of Pediatrics growth charts. Neurological assessment

was done by experienced physicians using the Amiel-Tison method [16].

All measurements were performed by investigators blinded to antenatal

studies.

Statistical analysis: Outcome variables were

compared between the study and the control groups. Statistical analyses

were performed by using SPSS (Version 16.0 for Windows, SPSS Inc.,

Chicago, IL) followed by the R package (Version 13.2.1). Fisher’s exact

test was used for categorical variables and for continuous variables the

student t-tests (normally distributed data) or Mann-Whitney U tests

(data not distributed normally) were used. Significance was accepted at

P<0.05. For multivariate analyses, initial exploration of

associations were performed using classification tree and random forest

methodology (not reported). Based on the initial exploratory analysis,

several responses were modeled as predictors of outcome of interest. The

odds ratio of a predictor adjusted for the presence of the other

predictors along with 95% confidence interval is reported.

We estimated that a sample size of 88 patients in

each group would provide 80% power at 95% confidence level to detect a

4-fold difference in risk of the primary outcome (death or major

neuromorbidity) between the groups.

Results

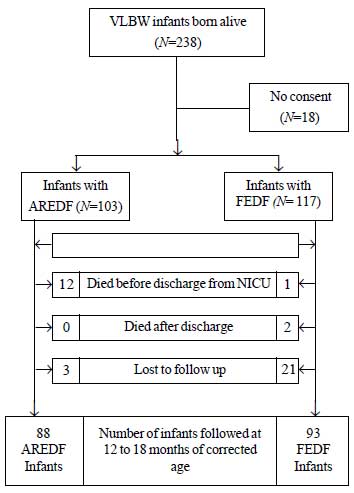

238 VLBW infants fulfilled the eligibility criteria.

Of these, 220 infants were analyzed for short-term outcomes. Long-term

outcomes were evaluated in 181 infants for growth and neurological

outcomes (Fig. 1). Compared to the AREDF group, more

infants in the FEDF group were lost to follow up (3.3% vs 18.6%,

P=0.001).

|

|

Fig. 1 Study flow chart.

|

Although the degree of prematurity did not differ,

the infants in the AREDF group were smaller compared with FEDF group.

Expectedly, more infants in the AREDF group were growth restricted at

birth. Delivery by Caesarean section, and oligohydramnios was

significantly higher in the AREDF group compared with the FEDF group. (Table

I).

TABLE I Baseline Characteristics of Study Infants

|

Variable |

AREDF group

|

FEDF group

|

|

N=103 |

N= 117 |

|

*Birth weighta (g)

|

1095

|

1260

|

|

(951-1288) |

(1080-1400) |

|

Gestationa (wk)

|

31 (30-33) |

31 (30-32) |

|

†Birth weight <1000g |

32 (31) |

20 (17) |

|

Gestation <30 wk

|

22 (21) |

24 (21) |

|

Males

|

52 (50) |

47 (40) |

|

*IUGR

|

59 (57) |

36 (31) |

|

Apgar scores (5min) |

8 (7-8) |

8 (7-8) |

|

#Cesarean delivery

|

103 (99) |

103 (88) |

|

*Singleton pregnancy

|

98 (95) |

79 (68) |

|

Antenatal steroids

|

95 (92) |

102 (87) |

|

Maternal age, mean (SD) |

27.2 (4.4) |

26.7 (4.7) |

|

PIH |

77 (75) |

92 (79) |

|

$Oligohydramnios

|

35 (34) |

25 (21) |

|

PROM |

1 (1) |

21 (18) |

|

#Preterm labor

|

2 (2) |

17 (15) |

|

Data shown as amedian (inter-quartile range), rest as n (%); *

P=0.001; #P=0.001; $P=0.05; †P=0.02; P≤0.05;

AREDF: absent/reversed end-diastolic umbilical artery Doppler

flow; FEDF=forward end-diastolic flow; IUGR=Intrauterine growth

restriction; PIH: Pregnancy induced hypertension; PROM: Preterm

rupture of membranes. |

Short-term outcomes: More infants had

hospital deaths in the AREDF group compared to the FEDF group (Table

II). Need for resuscitation at birth was similar between the groups,

but the incidence of respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) was higher in

the AREDF vs FEDF group. There was a tendency to need more

respiratory support in the AREDF vs FEDF group. However both the

groups were comparable for morbidities such as patent ductus arteriosus,

neonatal jaundice, chronic lung disease, and retinopathy of prematurity.

TABLE II Short-term Outcome of Study Infants

|

Outcome |

AREDF (n=103)

|

FEDF (n=117) |

P value |

|

Mortality

|

12 (12) |

1 (1) |

0.001 |

|

Delivery room resuscitation

|

16 (16) |

23 (20) |

0.48 |

|

Hypoglycaemia

|

8 (8) |

4 (4) |

0.23 |

|

Respiratory distress syndrome

|

33 (33) |

21 (19) |

0.02 |

|

Continuous positive airway pressure

|

32 (32) |

23 (20) |

0.06 |

|

Conventional ventilation

|

34 (34) |

26 (23) |

0.09 |

|

Necrotizing enterocolitis (³ Bell stage IIa)

|

15 (15) |

9 (8) |

0.13 |

|

Culture positive sepsis

|

24 (24) |

15 (13) |

0.051 |

|

Hemodynamically significant Patent ductus arteriosus

|

5 (5) |

12 (11) |

0.20 |

|

Chronic lung disease (supplemental O2 at 28d)

|

1 (1) |

3 (3) |

0.62 |

|

Retinopathy of prematurity (³stage II)

|

15 (15) |

11 (9) |

0.40 |

|

Abnormal cranial ultrasound

|

17 (17) |

13 (11) |

0.42 |

|

Cystic periventricular leukomalacia

|

10 (12) |

1 (1) |

0.004 |

|

Time to reach full feedsa (d) |

8 (6-10) |

7 (4-8) |

0.001 |

|

Duration of hospitalizationa (d) |

20 (14-29) |

15 (11-71) |

0.03 |

|

Data shown as amedian (inter-quartile range); Rest as n(%);

AREDF: absent/reversed end-diastolic umbilical artery Doppler

flow; FEDF= forward end-diastolic flow. |

Of the 17 infants with abnormal cranial ultrasounds

in the AREDF group, leucomalacia and the others had grade III-IV

intraventricular hemorrhage (Table II).

Long term outcomes: The odds for the combined

outcome of death or cerebral palsy (n=18,17% vs n=4,

3%, OR 5.9, 95% CI 1.9 to 25) was 5.9 times higher in the AREDF group

compared to the FEDF. Also AREDF infants showed a trend toward

higher risk for developing cerebral palsy compared to the FEDF infants (n=6,7%

vs n=1,1%: P=0.06). None of the infants in either

group were blind or had deafness. There were also no differences between

the groups in the incidence of microcephaly, short stature or poor

weight gain.

On logistic regression analysis for the short-term

outcomes after adjusting for ELBW (birth weight<1000g) and IUGR status,

AREDF continued to have an independent association with neonatal

mortality (OR 9.8, 95% CI 2.1- 46.4) and RDS (OR 2.4, 95% CI,1.1-5.0).

For the long-term outcomes, AREDF had an independent association with

the composite outcome of death or cerebral palsy (OR 8.4, 95% CI 2.3-

30.5) but not cerebral palsy or microcephaly alone.

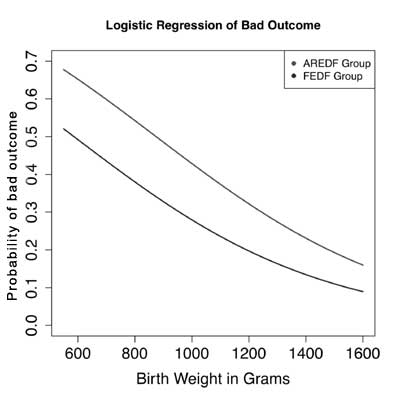

To better capture the contribution of AREDF in

neonatal outcomes, we examined all predictors of bad outcome in the

NICU. Since there were very few cases of chronic lung disease in this

population, bad outcome was defined as death or cystic periventricular

leukomalacia, or culture positive sepsis or necrotizing enterocolitis.

The only predictors that were significant were birthweight (P=0.01)

and Doppler flow status (P=0.05). To better model the

relationship between the predictors and bad outcome as a response, a

logistic regression curve of the probability of bad outcome as a

function of birth weight adjusted for AREDF or FEDF was fitted (Fig.

2). The preterm infants in the AREDF group had a consistently higher

probability of a bad outcome compared to the FEDF group with the

disadvantage being more pronounced at lower birth weights.

|

|

Fig. 2 Relationship between

birth-weight, umbilical Doppler flow patterns and outcome. Bad

outcome (defined as death or periventricular leukomalacia, or

culture positive sepsis or necrotizing enterocolitis); AREDF:

Absent/reversed end-diastolic unbilical artery doppler flow;

FEDF: Forward end-diastolic flow.

|

Discussion

In this cohort of moderately preterm infants with a

history of fetal growth restriction or exposure to pre-eclampsia,

demonstration of antenatal absent or reversed end-diastolic flow in the

umbilical artery was shown to increase the risk for neonatal death. This

study was specifically designed to prospectively compare outcomes after

AREDF vs FEDF, the gestational ages between the groups were

comparable, and the numbers of infants were relatively large permitting

meaningful comparisons. We evaluated both short-term and long-term

outcomes comprehensively with follow-up rates in excess of 90%, all

infants were enrolled in a 2-year time-span from a single-perinatal

center minimizing the confounding of changing or differing management

practices on the outcomes, and the groups were relatively homogenous in

that the underlying diagnosis was PIH in a great majority. To our

knowledge, the present study is the largest and the most comprehensive

report on the contribution of abnormal Doppler flow patterns, and IUGR

to outcomes in Indian preterm infants.

The higher neonatal mortality and morbidity in

infants with history of AREDF noted in this study is similar to previous

studies [17-21]. In comparison with these older studies, we had higher

numbers of infants with absent or reversed end-diastolic flow and the

gestational ages in both the groups were comparable. Consistent with the

reported literature, findings from the present study confirm that

birthweight and gestational age are more potent predictors of short-term

adverse neonatal outcomes in infants with IUGR, compared to Doppler flow

patterns. Interestingly, our data clearly demonstrated that despite

birth weight being a potent predictor of poor neonatal outcomes, the

diagnosis of AREDF had an independent adverse impact at all birth

weights with a more pronounced effect at lower birth weights.

For long-term outcomes, our study showed an

independent association of AREDF with the composite outcome of cerebral

palsy or death in infancy. This effect was largely due to increased

neonatal deaths. Interestingly, although the rate of PVL at term

gestation was higher in the AREDF group, this did not translate into an

increased risk for adverse neuromorbidity (cerebral palsy tended to be

more common in the AREDF group). A factor that may explain the lack of

adverse neurological outcomes despite increased rates of PVL is

developmental plasticity in the preterm [22]. In this regard, infants in

the early delivery arm of a randomized trial evaluating early vs.

delayed delivery in IUGR infants had an increased risk for adverse

neurodevelopmental outcomes at two years that was not sustained at

school age [23,24]. Studies of neurodevelopmental outcome in infants

with IUGR and abnormal Doppler flows have reported inconsistent

outcomes. Studies with smaller numbers of infants have reported adverse

neurological outcomes [9,10,25], while others failed to demonstrate

neurologic impairments [8,26]. These discrepancies largely appear to be

due to different patient populations and the degree of prematurity

appears to be a predominant determinant of adverse long term

neurological outcomes rather than abnormal Doppler flow patterns

[5,27,28].

The variables of birthweight, gestation, IUGR and

Doppler flow patterns are inevitably interlinked. In this regard a

randomized trial (GRIT trial) evaluated trade-offs between immediate

vs. delayed delivery in the management of preterm infants ~28 weeks

gestation with fetal growth restriction [29]. The immediate delivery

group had higher neonatal deaths but the stillbirth rate was higher in

the delayed group. Adverse neurological outcome at 2 years was more

common in the earlier delivery group, but these handicaps did not

persist at school age [23,24]. The prevalent practice at our study site

is to give maternal glucocorticoids and deliver infants within 48 hours

after demonstration of absent/reversed end-diastolic flow, similar to

the early delivery arm of the GRIT trial. Despite the immediate

delivery, fetuses with AREDF had an increased mortality and morbidity in

our study, suggesting that the umbilical Doppler changes may be a late

finding in the pathophysiology of fetal compromise in IUGR and pre-eclampsia

[27]. Alternatively, the fetuses in our study may have been sicker than

previously reported. Regardless, the findings are informative for

clinicians managing these high risk pregnancies .

Despite several strengths of our study, some

weaknesses were apparent. The study population was entirely from a large

referral perinatal center with a higher rate of IUGR and pre-eclampsia

than the general population. Lost to follow up was significantly higher

in the forward flow group. The study was not randomized. Therefore the

findings of the study may not be generalizable. We did not evaluate

multiple different ultrasound measurements of fetal well-being, because

umbilical artery doppler studies are the most commonly used modality at

most perinatal centers dealing with high risk pregnancies.

In a cohort of moderate preterm delivery with IUGR or

maternal pre-eclampsia, absent or reversed end diastolic umbilical

arterial blood flow independently increased the risk for neonatal

mortality, and had a trend towards increased incidence of cerebral palsy

at 12-18 months corrected age.

Acknowledgements: Professors Alan H. Jobe

(Cincinnati) and John P. Newnham (Perth) for review of the manuscript

and helpful suggestions.

Contributors: All the authors have written,

designed and approved the study.

Funding: NIH HD-57869 to SGK;

Competing interests: None stated.

|

What is Already Known?

•

Fetal growth restriction and abnormal Doppler flow studies

are commonly associated.

• Neonatal outcomes are not well known in

developing countries.

What This Study Adds?

•

Preterm IUGR infants with

antenatal abnormal umbilical artery doppler, are at increased

risk for immediate mortality and long term neurological

disabilities.

|

References

1. Brodsky D, Christou H. Current concepts in

intrauterine growth restriction. J Intensive Care Med. 2004;19:307-19.

2. Mandruzzato G, Antsaklis A, Botet F, Chervenak FA,

Figueras F. Intrauterine restriction (IUGR). J Perinat Med.

2008;36:277-81.

3. Bang AT, Baitule SB, Reddy HM, Deshmukh MD, Bang

RA. Low birth weight and preterm neonates: Can they be managed at home

by mother and a trained village health worker? J Perinatol.

2005;25:S72-81.

4. Figueras F, Gardosi J. Intrauterine growth

restriction: New concepts in antenatal surveillance, diagnosis, and

management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011

5. Baschat AA, Viscardi RM, Hussey-Gardner B, Hashmi

N, Harman C. Infant neurodevelopment following fetal growth restriction:

Relationship with antepartum surveillance parameters. Ultrasound Obstet

Gynecol. 2009;33:44-50.

6. Schreuder AM, McDonnell M, Gaffney G, Johnson A,

Hope PL. Outcome at school age following antenatal detection of absent

or reversed end diastolic flow velocity in the umbilical artery. Arch

Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2002;86:F108-14.

7. Torrance HL, Bloemen MC, Mulder EJ, Nikkels PG,

Derks JB, et al. Predictors of outcome at 2 years of age after

early intrauterine growth restriction. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol.

2010;36:171-7.

8. Valcamonico A, Accorsi P, Sanzeni C, Martelli P,

La Boria P, et al. Mid- and long-term outcome of extremely low

birth weight (elbw) infants: An analysis of prognostic factors. J Matern

Fetal Neonatal Med. 2007;20:465-71.

9 Ley D, Tideman E, Laurin

J, Bjerre I, Marsal K: Abnormal fetal aortic velocity waveform

and intellectual function at

7 years of age. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 1996;8:160-65.

10 Marsal

K, Ley D: Intrauterine blood flow and postnatal neurological development

in growth-retarded

fetuses. Biol Neonate 1992;62:258-64.

11. Devendra A, Sadhana D, Prem S, Prema K.

Significance of umbilical artery doppler velocimetry in the perinatal

outcome of growth restricted fetuses. J Obst Gynaec India.

2005;55:138-43

12. Malhotra N, Chanana C, Kumar S, Roy K, Sharma JB.

Comparision of perinatal outcomes of growth-restricted fetuses with

normal and abnormal umbilical artery Doppler waveforms. Indian J Med

Sci. 2006;60:311-7.

13. Goldenberg RL, McClure EM, Macguire ER, Kamath

BD, Jobe AH. Lessons for low-income regions following the reduction in

hypertension-related maternal mortality in high-income countries. Int J

Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;113:91-5.

14. Gravett MG, Rubens CE, Nunes TM. Global report on

preterm birth and stillbirth (2 of 7): Discovery science. BMC Pregnancy

Childbirth. 2010;10:S2.

15. Suresh S, Thangavel G. Mathemetical modeling of

fetal growth, Part I: data collection and descrtiptive statistics. IJMU.

2003;3;35-41.

16. Amiel-Tison C, Ellison P. Birth asphyxia in the

fullterm newborn: Early assessment and outcome. Dev Med Child Neurol.

1986;28:671-82.

17 Eronen M, Kari A,

Pesonen E, Kaaja R, Wallgren EI, Hallman M: Value of absent or

retrograde end-diastolic flow

in fetal aorta and umbilical artery as a predictor of perinatal

outcome in pregnancy-induced

hypertension. Acta Paediatr 1993;82:919-24.

18

Karsdorp VH, van Vugt JM, van Geijn HP, Kostense PJ, Arduini D et al:

Clinical

significance of absent or reversed end diastolic velocity waveforms in

umbilical artery. Lancet 1994;344:1664-68.

19. Yoon BH, Lee CM, Kim SW. An abnormal umbilical

artery waveform: A strong and independent predictor of adverse perinatal

outcome in patients with preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol.

1994;71:713-21.

20. Deshmukh A, Neelu S, Suneeta G. Significance of

umbilical artery Doppler velocimetry in the perinatal outcome of the

growth restricted babies. J Obst Gynaec India. 2010;l60:38-43.

21. Bora A, Mukhopadhyay K, Saxena AK, Jain V, Narang

A. Prediction of feed intolerance and necrotizing enterocolitis in

neonates with absent end diastolic flow in umbilical artery and the

correlation of feed intolerance with postnatal superior mesenteric

artery flow.J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009;22:1092-6.

22. Kostovic I, Judas M. Prolonged coexistence of

transient and permanent circuitry elements in the developing cerebral

cortex of fetuses and preterm infants. Dev Med Child Neurol.

2006;48:388-93.

23. Thornton JG, Hornbuckle J, Vail A, Spiegelhalter

DJ, Levene M. Infant wellbeing at 2 years of age in the growth

restriction intervention trial (grit): Multicentred randomised

controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:513-20.

24. Walker DM, Marlow N, Upstone L, Gross H,

Hornbuckle J, et al. The growth restriction intervention trial:

Long-term outcomes in a randomized trial of timing of delivery in fetal

growth restriction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:31-39.

25. Spinillo A, Montanari L, Bergante C, Gaia G,

Chiara A, et al. Prognostic value of umbilical artery doppler

studies in unselected preterm deliveries. Obstet Gynecol.

2005;105:613-20.

26. Kirsten GF, Van Zyl JI, Van Zijl F, Maritz JS,

Odendaal HJ. Infants of women with severe early pre-eclampsia: The

effect of absent end-diastolic umbilical artery doppler flow velocities

on neurodevelopmental outcome. Acta Paediatr. 2000;89:566-70.

27. Baschat AA, Odibo AO. Timing of delivery in fetal

growth restriction and childhood development: Some uncertainties

remain. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:2-3.

28. Walker DM, Marlow N. Neurocognitive outcome

following fetal growth restriction. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed.

2008;93:F322-5.

29. GRIT Study Group. A randomised trial of timed delivery for the

compromised preterm fetus: Short term outcomes and bayesian

interpretation. BJOG. 2003;110:27-32.

|

|

|

|

|