|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2009;46: 801-803 |

|

Cardiogenic Shock With Hypereosinophilic

Syndrome |

|

Vinitha Prasad, L Rajam and Ashwin Borade

From the Department of Pediatrics, Amrita Institute of

Medical Sciences and Research Centre, Kochi, Kerala, India

Correspondence to: Dr Vinitha Prasad, Professor of

Pediatrics, Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences and Research Centre,

Elamakkara (PO), Kochi, Kerala 682 026, India.

Email:

[email protected]

Manuscript received: April 25, 2008;

Initial review : May 22, 2008;

Accepted: September 22, 2008.

|

|

Abstract

We report a child with hypereosinophilic syndrome who

presented with cardiogenic shock. In addition, she had skin and joint

involvement. The clinical condition improved and eosinophil counts

normalized with steroid therapy. However, the skin lesions and

hypereosinophilia relapsed on stopping the steroids. The child was

subsequently maintained in remission on low dose prednisolone.

Keywords: Cardiogenic shock, Child, Hypereosinophilic syndrome.

|

|

Hypereosinophilic

syndrome (HES) is a rare disorder characterized by unexplained, persistent

eosinophilia and end organ damage due to eosinophilic infiltration. We

report a girl with HES who presented acutely with cardiogenic shock along

with skin and joint involvement.

Case Report

A 12-year old girl was admitted with fever, swelling of

knee and wrist joints for 2 weeks and skin rashes for 6 months. There was

no history suggestive of food or drug allergy, worm infestation, throat

pain, oliguria or dyspnea.

On examination, her pulse rate was 136/min, respiratory

rate 34/min and blood pressure 84/60 mm Hg. She had raised jugular venous

pressure, bilateral pedal edema and arthritis of bilateral knee and wrist

joints. There were erythematous papules with scaling on the extremities

and angioedema of the perioral and periorbital regions. There was no

pallor, icterus, cyanosis or clubbing. The anthropometry was normal.

Examination of the chest revealed bilaterally decreased air-entry in the

infrascapular areas. Cardiac apex was at the left 5 th

intercostal space in the mid clavicular line. Heart sounds were muffled.

There were no murmurs. She had tender hepatomegaly 4 cm below the right

costal margin (span 11 cm). Spleen was just palpable. Rest of the

systemic examination was normal.

Investigations revealed hemoglobin 12.4 g/dL, total

leucocyte count of 29,000/mm 3

(polymorphs 68.9%, lymphocytes 6%, eosinophils 22.2%, absolute eosinophil

count: 6438/mm3), platelet count 647 × 103/mm3 and erythrocyte

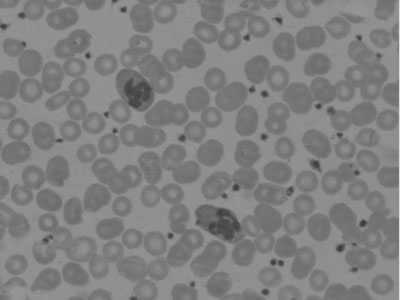

sedimentation rate of 8 mm in first hour. Peripheral blood smear showed

marked eosinophilia, few eosinophils showed multilobation of nuclei and

hypogranulation (Fig. 1). Other cells had normal morphology.

|

|

Fig.1 Peripheral smear showing eosinophils

with multilobation of nuclei and hypogranularity (Leishman stain X

100). |

Chest X-ray revealed mild pericardial effusion

and bilateral obliteration of costophrenic angles. ECG showed tachycardia

with low voltages. Echocardiogram on the second hospital day revealed a

small pericardial effusion, more over the right atrium (width 1.5 cm) and

a mild increase in the echogenicity of the myocardium. There was no

intracardiac thrombus, right ventricular dilatation, tricuspid

regurgitation or pulmonary artery hypertension. Her pulmonary artery

pressure was normal (mean pressure: 11mm Hg). Ultrasound abdomen showed

hepatomegaly, mild splenomegaly with ascites and bilateral mild pleural

effusion. Liver and renal function tests, PT and APTT were

normal.

Mantoux test, smear for malarial parasite,

microfilariae and stool examination for ova and parasites were negative.

ASO titer, Rheumatoid factor, ANA and anti-ds DNA were negative.

IgE levels were 400 IU/mL. Bone marrow aspirate showed

normocellular marrow with diffuse eosinophilia. Karyotype was normal. The

patient initially required ionotropic supports to stabilize the blood

pressure. Subsequently, a cardiac catheterization and endomyocardial

biopsy were performed. A right ventricular endomyocardial biopsy showed

hypertrophied myocardial fibres, eosinophilic infiltrates and moderate

interstitial fibrosis. Skin biopsy revealed dermal infiltration with

lymphocytes, plasma cells and few eosinophils.

Child was treated with oral prednisolone (1 mg/kg/day)

for 2 weeks. Thereafter, the steroids were gradually tapered and stopped

over 8 weeks. At 8 weeks, the WBC count was 12000/mm 3

with 0.2% eosinophils. The pericardial effusion resolved after a week. One

month after stopping the steroids, she developed fever, erythema and

angioedema over the face. The absolute eosinophil count was 2470

cells/mm3. Echocardiography was normal. She was started on prednisolone 1

mg/kg. Her skin lesions disappeared and eosinophil counts became normal

after 4weeks. She has been maintained on low dose alternate day

prednisolone (0.25 mg/kg) and is asymptomatic without peripheral

eosinophilia.

Discussion

Hyperosinophilic syndrome (HES) is a rare disease in

children, the exact prevalence is not known(1). The diagnostic criteria

for "idiopathic HES" proposed in 1975 are blood eosinophilia > 1500

cells/mm 3 for at least 6 months,

absence of an underlying cause of eosinophilia despite extensive

evaluation, and presence of end organ damage or dysfunction due to

eosinophil infiltration(2). Heart, skin and nervous system are most

frequently involved. Eosinophils release many cytotoxic substances like

eosinophil-derived neurotoxin, eosinophil cationic protein, major basic

protein, reactive oxygen species and proinflammatory cytokines, producing

end organ damage and fibrosis(2). HES must be distinguished from

eosinophilic leukemia, which is characterized by increased blood and bone

marrow blasts, eosinophilic clonality and specific cytogenetic

abnormalities(2).

Recently three subtypes of HES have been identified(3).

The myeloproliferative variant (m-HES) is characterized by an interstitial

deletion in chromosome 4q12 in cells of the myeloid lineage and

FIP1L1-PDGFRA gene fusion. Supportive evidence of m-HES includes

splenomegaly, anemia, throm-bocytopenia, increased circulating myeloid

pre-cursors, dysplastic eosinophils, elevated serum vitamin B12 and

altered leucocyte alkaline phosphatase levels. Leukemic transformation can

occur. The lymphoproliferative variant (l-HES) is associated with clonal

proliferation of phenotypically abnormal T cells. Idiopathic HES is a

subtype of the disease that is not associated with a specific chromosomal

or clonal abnormality. Our patient had overlapping characteristics of

myeloproliferative and lympho-proliferative variants.

A combination of eosinophilic myocarditis and

pericarditis with effusion contributed to the heart failure and shock in

our patient. Pulmonary embolism was ruled out. Biopsy showed myocardial

hypertrophy and moderate fibrosis, but repeat echocardiography did not

reveal any restrictive cardiomyopathy. It is possible that significant

ventricular thickening had not yet occurred, which could be detected by

routine echocardiography.

Our patient had no previous documented

hypereosinophilia and did not fulfill the classic duration criteria. She

presented with marked eosinophilia and serious cardiac involvement, which

required immediate treatment(2,4).

Corticosteroids are the initial treatment, except in

FIP1L1-PGDFRA gene fusion causing mutation. Hydroxyurea, interferon alpha,

anti IL-5 antibody mepolizumab, imatinib mesylate and bone marrow

transplantation are other therapeutic options. Anticoagulants are required

for patients with intracardiac thrombosis(5,6).

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge Dr Edwin Francis MD, DM,

Associate Professor, Department of Pediatric Cardiology, Amrita Institute

of Medical Sciences, for performing the cardiac catheterisation and

myocardial biopsy of our patient.

Contributors: VP and AB were involved in the

management of the patient, drafting the manuscript and review of

literature. LR was involved in the management of the patient and will act

as a guarantor for the paper.

Funding: None.

Competing interest: None stated.

References

1. Katz HT, Haque SJ, Hsieh FH. Pediatric

hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) differs from adult HES. J Pediatr 2005;

146: 134-136.

2. Roufosse F, Cogan E, Goldman M. Recent advances in

the pathogenesis and management of hypereosinophilic syndromes. Allergy

2004; 59: 673-689.

3. Wilkins HJ, Crane MM, Copeland K, Williams WV.

Hypereosinophilic syndrome: an update. Am J Hematol 2005; 80:148-157.

4. Weller PF, Bubley GJ. The idiopathic

hypereosinophilic syndrome. Blood 1994; 83: 2759-2779.

5. Ogbogu P, Rosing DR, Horne MK. Cardiovascular

manifestations of hypereosinophilic syndromes. Immunol Allergy Clin North

Am 2007; 27: 457-475.

6. Gotlib J, Cools J, Malone JM, Schrier SL, Gilliland

DG, Coutre SE. The FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion tyrosine kinase in

hypereosinophilic syndrome and chronic eosinophilic leukemia: implications

for diagnosis, classification and management. Blood 2004; 103: 2879-2891.

|

|

|

|

|