Shanthi Ananthakrishnan

and P. Nalini

From Jawaharlal

Institute of Post Graduate Medical Education and Research (JIPMER),

Pondicherry, India.

Correspondence to: Dr.

Shanthi Ananthakrishnan, Type 5/1, Danvantri Nagar, Pondicherry 605

006, India. E-mail:

ananth4@vsnl.com

Manuscript received:

November 28, 2001, Initial review completed: December 26, 2001;

Revision accepted: March

6, 2002.

This study was

conducted to estimate the magnitude of school absenteeism and

determine its causes in a village in Tamilnadu. The sample included a

cohort (n=143) followed for one year and a cross sectional sample (n =

278). The mean number of episodes of school absenteeism was 1.6 ±

0.6/ child/year and the mean number of days lost was 1.5 ± 1.4

days/child/year. It is estimated that on a working day of the school,

about 0.85% of the student population will be absent. Common causes of

absenteeism were adverse weather conditions, work, illness and social

customs. School absenteeism was found to be higher during rainy season

and local groundnut picking season (October-December) than during

other months. If possible, school based programs may be avoided during

months with maximal absenteeism.

Key Words:

School absenteeism, school based programs.

Schools are increasingly

being recognized as effective tools to reach the community(1). School

based screening and intervention programs have helped in developing and

implementing control measures for several disorders of public health

importance(2-4). However, the effectiveness of these programs depends on

the number of children attending schools. School absenteeism is an

important issue, which affects not only educational achievement but also

results in false estimation of the prevalence of disease in school based

screening programs. Further, school based intervention programs may miss

out several affected children(5,6). This study was, therefore, carried

out to estimate the magnitude of school absenteeism and identify its

causes.

Subjects and Methods

The study was carried out

in Kedar (population, 3,000), a village in Tamil Nadu, about 65 km. to

the southwest of Pondicherry, South India. Basic demographic details of

the village was obtained by doing a house to house survey. The

objectives of the study were explained to and informed consent was

obtained from the village leader, parents, teachers and children to

participate in the study. Most of the villagers were either landless

agricultural labourers or weavers and were socioeconomically backward

with an average per-capita income of Rs. 2,201 ± 36 per annum. The

village has 2 government schools - a primary school and a high school

with a middle school section. A total of 1,881 children were studying in

the school out of which about 50% were from neighbouring villages. There

is a government sponsored midday meal scheme providing supplementary

nutrition (300 - 400 calories and 15- 20 g protein per day/child) to all

children studying in both the schools.

Out of a total of 658 families in the

study village, 100 families were randomly selected and all children

studying in school from these families formed the cohort. They were

followed up fortnightly for one year. Information on school attendance

and reasons for absenteeism, if any, was obtained and entered on a

structured format.

In a cross sectional

survey, classes I-X of the government schools in the study village were

visited at the rate of one class per day on 10 consecutive working days

in the mornings. In each class, students who were absent the previous

day, but were present on the day of the visit were interviewed with a

structured questionnaire as to the cause of absence the previous day.

Data were obtained only from those students who had absented themselves

the whole day.

Statistical tests used

for analysis were chi-square test for comparing proportions and Student’s

‘t’ test for comparing means. Alpha error was fixed at 5%.

Results

Cohort Study

There were a total of 664

children attending school from the study village out of which 143

children including 54 girls and 89 boys were in the cohort. In the study

village, the proportion of children between 5-17 years of age who had

been enrolled in school at sometime or the other was 89.5%. However, at

the time of study, the proportion of children actually attending school

in the primary section (5-11 years), middle school section (12-14 years)

and high school section (15-17 years) were 80.8%, 80.5% and 53.4%

respectively.

Over a period of one

year, 30 out of 54 (55.5%) girls and 40 out of 89 (44.9%) boys had

absented from school on one or more occasions. The total number of days

lost was 210 and the mean number of days lost was 1.5 ± 1.4

days/child/year (estimated for the cohort; n = 143). The total

number of episodes of absenteeism was 110 (50 in girls and 60 in boys).

The mean number of episodes of school absenteeism was

1.6 ± 0.6/child per year (estimated for those who

were absent; n = 70). There was no significant gender difference

in either the number of episodes of absenteeism or the number of days

lost (P > 0.05). Given the total number of working days in an

academic year as 180 and a mean loss of 1.5 days/child/year, in the

study school which has a strength of 1,881 students it is estimated that

on any working day about 16 students (0.85%) are likely to be absent.

Out of all absenteeism episodes, 53.6% were among primary school

children, 33.6% among middle school children and 12.7% among high school

children. The maximum number of episodes (66.3%) of absenteeism occurred

during the monsoon months, (October-December) and the minimum (9.1%)

between January-March.

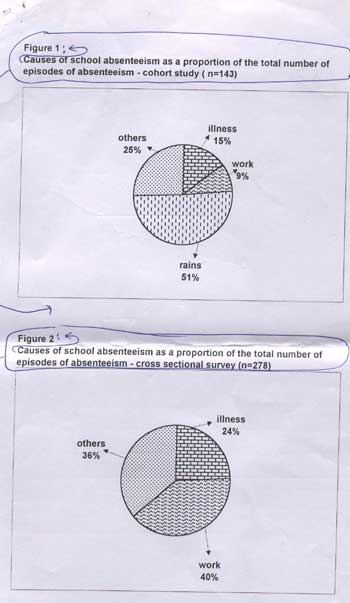

The most common cause of absenteeism was

inclement weather conditions during monsoon followed by other causes

such as social functions at home/village and social visits (Fig. 1).

Illness or work was not a major cause of school absenteeism. One episode

of

absenteeism was due to an

acute illness in the mother. The mean number of episodes of school

absenteeism due to illness was 0.22/child/year and the mean number of

days lost due to illness 3.2 ± 2.2 days/episodes and the corresponding

figures for work were 0.12/child/year and 1 ± 0.5 days/episode.

Cross Sectional Survey

A total of 278 children

(117 girls & 161 boys) were found to be absent during the cross

sectional survey. Highest number of absentees were in the middle school

section (59.3%) followed by primary school (24.8%) and high school

SECTIONS (15.8%). The most common cause of absence was work followed by

illness and other causes (Fig.2). The survey was conducted in

October which happened to be groundnut picking season in that area. Many

children had gone to pick groundnuts and hence work (extra scholastic)

was observed to be the most common cause of school absenteeism. Apart

from groundnut picking, the nature of work that caused school absence

was often trivial such as fetching water, carrying food, going to the

market etc. which took about one hour only. Illness (24.1%) as a

cause of absenteeism was significantly less (P < 0.05) than that due

to work (39.6%) or other causes. Illnesses that caused school

absenteeism were fever, headache and abdominal pain. There was no

significant gender difference with respect to the cause of absenteeism

(P > 0.05).

Discussion

The current study shows that school

absenteeism is not a major issue among school children in the study

village. This is perhaps due to the mid-day meal scheme which has been

effective in improving school enrollment and attendance(7). The higher

proportion of work as a cause of school absenteeism in the cross

sectional survey could be due to the fact that the survey was conducted

during groundnut picking season when many children especially in the age

group 10-15 years were away for picking groundnuts. In areas where there

are seasonal crops and school children are useful in field work, school

timings could be made flexible so that children could learn and earn at

the same time. The reality in the village is that there is tremendous

economic pressure from the family for the child to earn and add to the

family income whenever possible. In this context, flexible school

timings will atleast ensure that the child gets some education since,

children preferred to stay away from school rather than attend late

since it involved punishment or fine. Rigidity in the educational system

in the presence of economic pressure might drive the child away from

learning to earning and eventually lead to dropping out of school.

Adverse weather

conditions during monsoon was to a large extent responsible for school

absenteeism in this study. The main reasons for this could be that most

of the classes functioned from thatched sheds which could not brave the

rains besides inability of some children (particularly those who are

from neighbouring villages) to reach the school due to difficulties in

commuting. School based screening and intervention programs could

therefore be avoided during these months in the study village.

A common cause of school

absenteeism observed in the present study was social functions at home

and in the community. Children were often asked to stay at home to help

or to escort female members of the family to neighbouring villages to

attend some functions. This points to a lack of discipline among not

only children but also elders and the priortization of social customs

over education.

Since this study

pertained to only a particular village, the conclusions cannot be

generalized. Further studies need to be carried out in several areas

varying in literacy rates, social and cultural values, etc.

before drawing meaningful and relevant conclusions on school

absenteeism.

Contributors:

SA designed and conducted the study and shall act as guarantor for the

paper. PN helped in designing the study. The manuscript was written by

both the authors.

Funding: None.

Competing interests:

None stated.

|

Key

Messages |

| •

School absenteeism in general and due to illness in particular are

not important problems among school going children in rural Tamil

Nadu. |