|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2021;58: 994-996 |

|

Anakinra in Refractory Multisystem

Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C)

|

|

Chandrika S Bhat,1* Rakshay Shetty,2 Deepak Ramesh,2

Afreen Banu,2 Athimalaipet V Ramanan3

From 1Pediatric Rheumatology Services, and 2Pediatric

Intensive Care Services, Rainbow Children’s Hospital, Bangalore,

Karnataka, India; 3Bristol Royal Hospital for Children and Translational

Health Sciences, University of Bristol, United Kingdom.

Email:

[email protected]

|

|

A small proportion of children can develop a hyper-inflammatory

condition 2 to 4 weeks following an infection or exposure to SARS-CoV2

virus termed interchangeably as multisystem inflammatory syndrome in

children (MISC) or Pediatric Inflammatory Multisystem Syndrome

temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2 virus (PIMS-TS) [1]. The patho-genesis

of this novel condition remains elusive and treatment protocols are

predominantly empirical. Intravenous immuno-globulin (IVIG) alone or

with corticosteroids are the suggested first line agents [2,3]. In those

with refractory disease (defined by the presence of persistent fever

and/or significant end-organ involvement despite initial

immunomodulation), second line treatment options include IL-1, IL-6, and

tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blockers [2,3]. The PIMS-TS arm of the

RECOVERY trial is currently evaluating tocilizumab and anakinra for

refractory disease [5]. The experience with use of anakinra in India is

sparse due to non-availability of the drug. We report our experience

with the use of anakinra in two children with refractory MISC.

Case 1: A 11-year-old boy was referred for fever,

abdominal pain and diarrhea of 5 days duration. At presentation he was

hypotensive (BP 70/40 mm Hg) with bilateral non purulent conjunctival

suffusion and an erythematous maculopapular rash over his trunk.

Investigations revealed lymphopenia (total white blood cell count (WBC)

4,350/ìL, lymphocytes 4%), elevated inflammatory markers (CRP 170 mg/L,

ESR 72 mm/hour, LDH 359 U/L, ferritin 1,200ng/mL, d-Dimer 12,500ng/mL),

hyponatremia (130mEq/L) and increased NT-proBNP levels (>20,000pg/mL).

Serology was positive for IgG SARs-CoV-2 antibodies (Chemiluminescence,

titer 74.9 AU/mL). An echocardiogram showed decreased left ventricular

function (LVEF, 40%). A diagnosis of MIS-C was considered, and he was

given IVIG (2 g/kg) with intravenous methylprednisolone (IVMP) (2

mg/kg). Noradrenaline infusion (0.15 µg/kg/min) for hypotension and

empirical antibiotics were commenced simultaneously. The dose of

methylprednisolone was increased (10 mg/kg, once daily for three days),

and adrenaline infusion (0.15 µg/kg/min) was started for persistent

hypotension. He continued to be febrile and hypotensive with elevated

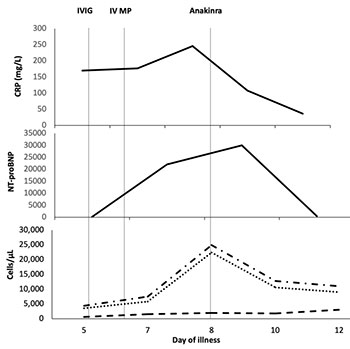

inflammatory markers (Fig. 1a). Considering refractory disease,

anakinra (5 mg/kg/day in two divided doses, subcutaneously) was

initiated. There was a dramatic improvement in his clinical status with

abrupt cessation of fever and normalization of blood pressure within 12

hours. LVEF increased subsequently (60%). Anakinra was discontinued

after 48 hours, and he was discharged on a tapering dose of steroids and

aspirin. On follow up at two- and six weeks, LVEF continued to be

normal.

|

|

|

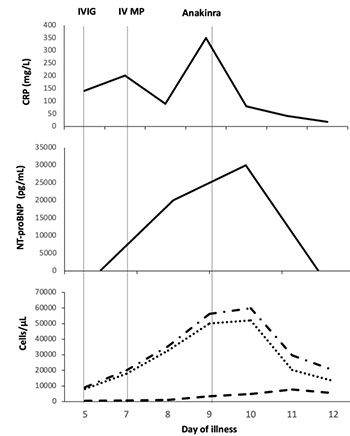

IVIG- intravenous immunoglobulin (2 g/kg),

IVMP- intravenous methylprednisolone (10mg/kg once daily)

Fig. 1 Trend of inflammatory markers and therapeutic

interventions in (a) Case 1 and (b) Case 2.

|

Case 2: A 9-year-old boy presented with fever and

diarrhea of five days. On examination, he had bilateral conjunctival

suffusion, red lips, strawberry tongue, erythematous maculo-papular

rash, and pedal edema. Investigations revealed lymphopenia (WBC count

9,230/µL, lymphocyte 6%), elevated acute phase reactants (CRP 140 mg/L,

ESR 60 mm/hr, ferritin 596 ng/mL, d-Dimer 9120 ng/mL), and hyponatremia

(127 mEq/L). He tested positive for IgG SARs-CoV-2 anti-bodies (Biomerieux,

Index 10.95). An echocardiogram showed dilatation of the right coronary

artery (RCA, z-score 2.19). His presentation was consistent with

Kawasaki disease like phenotype of MISC and he was given IVIG (2 g/kg)

with IVMP (2 mg/kg/day). On day 3 of admission, fever recurred, and he

developed hypotension necessitating inotropic support (noradrenaline,

0.15 µg/kg/min). Inflammatory markers and NT-proBNP levels had further

increased (Fig. 1b). Repeat echocardiogram showed a decrease in

LVEF (35%) and progression of RCA involvement (z-score 3.5). The dose of

methylprednisolone was increased to 10 mg/kg once daily for 3 days. On

day 5 of admission, his inotropic requirement (adrenaline, 0.5

µg/kg/min) and inflammatory markers progressively increased. Anakinra (6

mg/kg/day in two divided doses, subcutaneously) was commenced for

refractory disease. Within 48 hours, he was off inotropic support with

defervescence of fever, down trending inflammatory markers and normal

LVEF (60%). He was discharged on a slow taper of oral steroids and

aspirin. On follow up at two- and six weeks, coronary vessels and LVEF

were within normal limits.

Anakinra is a recombinant IL-1R antagonist that

blocks the binding of both IL-1 a

and IL-1b to

IL-1R, thereby inhibiting the proinflammatory effects of IL-1. According

to the American College of Rheumatology clinical guidance, anakinra

(4-10 mg/kg/day) is the preferred monoclonal antibody in refractory

MIS-C [4]. However, the United Kingdom national consensus guidance

recommends tocilizumab, anakinra or infliximab depending on clinician

preference [3]. In comparison to tocilizumab or infliximab, the short

half-life of anakinra makes it more favorable for use in the Indian

context where secondary infections are a cause of concern. In fact,

anakinra was found to be beneficial in patients with severe

sepsis, especially in the subset with macrophage activation syndrome

[6]. The cost of treatment with anakinra compares favorably with

tocilizumab. Our experience re-emphasizes that anakinra can be an

effective therapeutic agent in children with MISC who do not respond to

IVIG and corticosteroids.

REFERENCES

1. Bhat CS, Gupta L, Balasubramanian S, Singh S,

Ramanan AV. Hyperinflammatory syndrome in children associated with

COVID-19: Need for awareness. Indian Pediatr. 2020;57: 929-35.

2. Fouriki A, Fougère Y, De Camaret C, et al.

Case series of children with multisystem inflammatory syndrome following

SARS-CoV-2 infection in Switzerland. Front Pediatr. 2021;8:594127.

3. Harwood R, Allin B, Jones CE, et al. PIMS-TS

National Consensus Management Study Group. A National Consensus

Management Pathway For Paediatric Inflammatory Multisystem Syndrome

Temporally Associated With COVID-19 (PIMS-TS): Results of a National

Delphi Process. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2021;5:133-41.

4. Henderson LA, Canna SW, Friedman KG, et al.

American College of Rheumatology Clinical Guidance for Multisystem

Inflammatory Syndrome in Children Associated With SARS-CoV-2 and

Hyperinflammation in Pediatric COVID-19: Version 2. Arthritis Rheumatol.

2021;73:e13-e29.

5. Nuffield Department of Population Health.

Information for site staff 2020. Accessed June 21, 2021. Available from:

https://www.recoverytrial .net/for-site-staff

6. Shakoory B, Carcillo JA, Chatham WW, et al.

Interleukin-1 receptor blockade is associated with reduced mortality in

sepsis patients with features of the macrophage activation syndrome:

Re-analysis of a prior phase III trial. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:275-28.

|

|

|

|

|