|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2021;58:973-977 |

|

Gastric Lavage for Prevention of Feeding

Intolerance in Neonates Delivered Through Meconium-Stained

Amniotic Fluid: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

|

|

Poonam Singh 1, Manish

Kumar2, Sriparna Basu1

From 1Department of Neonatology, All India Institute of Medical

Sciences, Rishikesh; 2Department of Pediatrics, All India Institute of

Medical Sciences, Gorakhpur, Uttar Pradesh.

Correspondence to: Dr Sriparna Basu, Professor, Department of

Neonatology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Rishikesh,

Uttarakhand 249203, India.

[email protected]

PROSPERO Registration Number: CRD42020159723

Published online: April 17, 2021;

PII: S097475591600310

|

Background: The role of gastric lavage in

neonates delivered through meconium-stained amniotic fluid remains

unclear.

Objective: This study evaluated the effects of

gastric lavage, compared to no gastric lavage, on the incidences of

feeding intolerance, respiratory distress, meconium aspiration synd-rome,

time to establish breastfeeding, hospitalization and pro-cedure-related

complications in late-preterm and term neonates delivered through

meconium-stained amniotic fluid.

Design: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Data sources and selection criteria: MEDLINE,

EMBASE, CENTRAL, and other databases were searched for randomized

controlled trials and quasi-randomized controlled trials using search

terms: neonate OR newborn infant, meconium OR meconium-stained amniotic

fluid, and lavage OR gastric lavage from inception to May 2020. Data

were pooled in RevMan and analyzed in GRADE.

Results: Pooled effects (9 randomized controlled

trials, number=3668), showed a significant reduction in the incidence of

feeding intolerance (relative risk 0.70; 95% confidence interval

0.58,0.85, I2=0) after gastric lavage. No difference was observed for

the incidence of meconium aspiration syndrome (4 studies) or

procedure-related complications (7 studies). Only one study, reporting

the proportion of neonates with low oxygenation (SpO2<85%), did not find

any significant difference. No study evaluated the effects of gastric

lavage on respiratory distress, breastfeeding, and hospitalization.

Conclusions: Low-quality evidence supported the

role of gastric lavage for the prevention of feeding intolerance in

late-preterm and term neonates born through meconium-stained amniotic

fluid. Applicability of results was limited by the high risk of bias.

Well-conducted randomized controlled trials with impor-tant patient

outcomes are needed before recommending the practice of gastric lavage.

Keywords: Feeding intolerance, Gastric lavage, Meconium-stained

amniotic fluid, Neonate

|

|

M

econium-stained

amniotic fluid, complicating 9-12% of all deliveries [1,2], may

be associated with recurrent vomiting and

feeding intolerance, due to meconium-induced chemical gastritis

[3], which may delay the establishment of oral feeding resulting

in a risk of hypoglycemia, need for parenteral fluid therapy [4]

and a possibility of secondary meconium aspiration [5]. Though a

quasi-randomized study showed the benefit of gastric lavage

performed in the delivery room in reducing feeding intolerance

[6], later randomized controlled trials (RCTs) failed to

document benefit [5,7-14]. Though oro/nasogastric feeding tube

placement and gastric lavage are apparently simple procedures,

complications such as feeding tube placement errors, oxygen

desaturation, bradycardia, gastric, and esophageal perforation,

are often reported [15-19]. A previous meta-analysis in 2015 [4]

included 6 studies and found limited evidence to favor gastric

lavage to reduce the incidence of feeding intolerance in infants

delivered through meconium-stained amniotic fluid. This

systematic review and meta-analysis intended to identify,

appraise, and synthesize available evidence regarding the

efficacy and safety of gastric lavage after initial delivery

room stabilization, to prevent feeding intolerance, among

neonates delivered through meconium-stained liquor.

METHODS

The protocol for this systematic review was

registered in the International Prospective Register of

systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) database. This systematic review

was conduc-ted and reported as per Preferred Reporting Items for

Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [20].

Search eligibility and search strategy:

The review included RCTs and quasi-RCTs comparing the effect of

prophylactic gastric lavage with normal saline versus no lavage

after initial stabilization at delivery room, before initiation

of feeding, in late-preterm and term neonates delivered through

meconium-stained amniotic fluid on the prevention of feeding

intolerance. Feeding intole-rance was defined as gastric residue

³30%

of the previous feed, and/or regurgitation, abdominal

distension, emesis/retching [21]. The primary outcome was the

incidence of feeding intolerance, secondary outcomes being

inci-dences of respiratory distress and meconium aspiration

syndrome, need and duration of respiratory support, time to

establish breastfeeding, exclusive breastfeeding rate at

discharge, duration of hospital stay, and the adverse effects of

gastric lavage Crossover trials, non-English publications, and

conference abstracts were excluded.

All authors independently searched the

databases MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of

Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Cumulative Index to Nursing and

Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Google Scholar, Scopus, and

Web of Science, from inception to May, 2020. Details of search

words and search results are given in

Web Table I. The

references of full text articles were checked for possible

inclusion as additional articles.

Data extraction and quality assessment:

After removing duplicates, individual study details were

extracted in a pre-designed format by two authors (PS, MS)

indepen-dently, including author, year of publication,

geographic location, study period, research design, sample size

(calculated and analysed total and in each group), inclusion and

exclusion criteria, procedure details, characteristics of

participants, including mean gestation, birth weight, gender,

thick/thin meconium, definitions and incidences of outcomes. Any

disagree-ment related to collated data was resolved by the third

author (SB).

Quality of studies was assessed independently

by all authors using Cochrane Collaborations Risk of Bias tool

[22] based on the domains: random sequence generation;

allocation concealment; blinding of participants and personnel;

blinding of outcome assessment; incomplete outcome data;

selective outcome reporting; other bias. Any disagreement was

resolved by mutual discussion.

Statistical analysis: Statistical

analysis was performed using Review Manager Version 5.3 [23].

Relative risk (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) was

calculated for all primary and secondary outcomes. Risk

difference (RD) and number needed to benefit/harm were also

calcu-lated. Heterogeneity was assessed using I 2

statistics. A fixed or random-effects model was used based on

heterogeneity. Random-effects model was used where heterogeneity

was more than 50%. Sub-group analysis was done in possible areas

of heterogeneity such as consistency of meconium,

vigorous/non-vigorous, need of positive pressure ventilation

(PPV), and the postnatal age of performing gastric lavage.

Grading of Recommen-dations Assessment, Development, and

Evaluation (GRADE) approach [24] was applied to assess the

quality of evidence for the predefined outcomes.

RESULTS

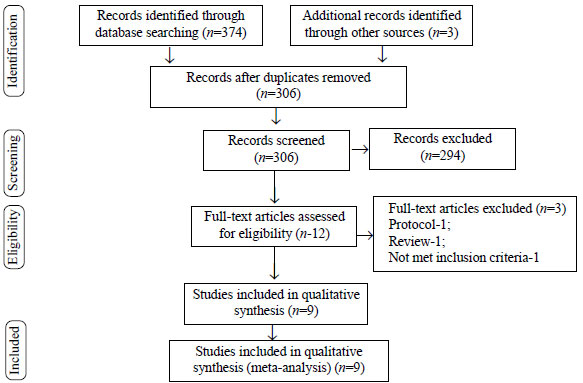

Out of the initial database search of 374

articles and 3 additional articles through manual search, 12

articles were retrieved, after screening titles, abstracts and

removing duplicates. Of these, 9 studies, including 3668

neonates [5-13], met our inclusion criteria and were subjected

to meta-analysis (Fig.1). The characteristics of the

studies included in this review are summarized in

Web Table I.

Seven trials were conducted in India [5,7-10,12,13], and two

were conducted in Saudi Arabia [6] and Nepal [11]. Two studies

were quasi-randomized [6,10], while the rest were RCTs. The

study population was homogenous across the studies. All studies

included vigorous late-preterm and term neonates born through

MSAF, who did not develop respiratory distress at birth.

|

|

Fig. 1 PRISMA flow diagram.

|

The definition of feeding intolerance varied

across the studies. While five studies [5,7,10-12] defined

feeding intolerance as vomiting, abdominal distension, and

increased gastric residuals, two studies [6,9] considered

vomiting and retching and one study took vomiting and abdominal

distension as a signs of feeding intolerance [13]. Singh, et al.

did not mention the criteria of feeding intolerance in their

trial [8]. Very slow feeding/poor suck was considered a

component of feeding intolerance in the study of Narchi, et al.

[6]. Period of observation for feeding intolerance ranged from

48-72 hours [5,7-12] or till discharge [7,9] whereas it was not

specified by Narchi, et al. [6] and Yadav, et al. [13].

The procedure of gastric lavage varied across

the studies, using feeding tubes of variable sizes, 6 Fr

[10-12], 8 Fr [7,9,10,13] or 10 Fr [5] through oral [5,9] or

nasal route [7,10-13] and lavage being conducted using 10 mL/kg

[5,7,10-13] or 20 mL [9] of normal saline [5,7,9-13] in the

aliquots of 5 mL [10] or 10 mL [7,11,12]. Feeding intolerance

was the primary outcome in seven studies [6,7,9-13], while

proportion of infants developing meconium aspiration syndrome

within 72 hours of age [5] and the need for subsequent gastric

lavage [8], respectively, were the primary outcomes in the other

two studies. Only one study monitored the procedure of gastric

lavage using a pulse oximeter [5].

Web Fig. 1A and

Web

Fig. 1B summarize the quality of the studies. There

was no publication bias as per the Funnel plot (Web Fig.2).

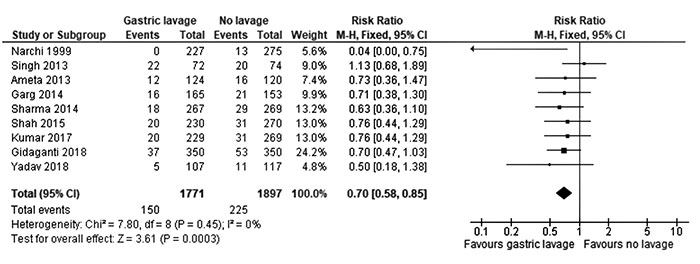

Gastric lavage resulted in a significant

reduction of feeding intolerance (pooled RR 0.70; 95% CI 0.58 to

0.85, I 2 0%), with a

risk difference of -3.39% (95% CI -5.34 to -1.44), and number

needed to benefit being 29.5 (95% CI 18.69 to 69.83) (Fig. 2).

Subgroup analysis of two trials [6,7] in neonates delivered

through thick meconium-stained amniotic fluid did not find any

significant difference, though pooling of data could not be done

due to incomplete reporting. Sensitivity analysis performed

after the inclusion of only RCTs [5,7-9,11-13] and those with a

uniform definition of feeding intolerance [5,7,10-12] also

showed significant beneficial effects of gastric lavage (Web

Table II).

|

|

Fig. 2 Forest plot analyzing the

incidence of feeding intolerance in neonates with and

without gastric lavage.

|

While none of the neonates in any group

developed meconium aspiration syndrome in three studies

[8,9,13], one study [5] reported insignificant difference in the

incidence of meconium aspiration syndrome between gastric lavage

and no-gastric lavage group. No difference was observed across

the studies in the incidences of bradycardia [5,7,9-13],

desaturation/cyanosis [5,7,11,12] or local trauma [5-7,9-13],

between neonates with and without gastric lavage. One study [5]

reported no significant difference in the proportion of neonates

with low oxygenation (SpO2<85%

at 15 minutes of life) between the groups. None of the studies

reported complications like secondary vomiting, aspiration,

respiratory distress [6,7,9,10] or apnea [5-7, 9-13].

The time of establishment of breastfeeding,

exclusive breastfeeding rate at discharge, need and duration of

respiratory support, as well as complications like feeding tube

placement errors and gastric/esophageal perforation were not

reported by any of the studies.

The quality of evidence assessed using the

GRADE (Web Table III), shows that except for the

incidence of feeding intolerance, the effect size of other

outcomes was non-estimable due to the small number of

occurrences.

DISCUSSION

In the present systematic review, low-quality

evidence from nine RCTs showed that gastric lavage performed

immediately after delivery room stabilization before initiation

of feeding resulted in a significant reduction in the incidence

of feeding intolerance in vigorous late preterm and term

neonates born through meconium-stained amniotic fluid. None of

the studies reported any adverse events related to gastric

lavage and none of the studies looked for feeding tube placement

errors and gastric/esophageal perforation.

The studies included in this review had high

rates of bias, mainly attributable to lack of allocation

conceal-ment, quasi-randomized design [6,10] and absence of

blinding of the outcome assessors [5-13]. Seven studies

evaluated the adverse effects of gastric lavage in the form of

apnea, bradycardia, local trauma or cyanosis and no difference

was found between the groups [5,7,9-13]. Narchi, et al. [6]

assessed for apnea and local trauma, which was not documented in

any study neonate. Though all the studies reported gastric

lavage to be a safe procedure, desaturations were not evaluated

with pulse oximeters, except in one study [5]. The route of

feeding tube placement being non-uniform across studies, it

could affect the incidence of adverse effects [25]. Gastric

aspiration with feeding tube placement has been shown to

increase the mean arterial blood pressure, retching, disruption

of pre-feeding behavior [26], with the development of functional

gastrointestinal disorders later in life [27].

None of the studies have mentioned the time

of occurrence of vomiting/retching in relation to the procedure

or the initiations of feeds. The definition of feeding

intolerance was not uniform across the studies. Slow/poor

sucking, taken as feeding intolerance, by a study is more

suggestive of neurological problems or immaturity. None of the

studies have evaluated the effect of the intervention on

clinically more relevant outcomes such as time to establish

breastfeeding, exclusive breastfeeding rate at discharge, or

initiation of immediate skin-to-skin contact in the delivery

room.

Gastric lavage can potentially affect the

incidence of meconium aspiration syndrome. While on one hand,

gastric lavage may prevent meconium aspiration syndrome by

clearing meconium from the stomach, thereby preventing

subsequent vomiting and aspiration [3]; on the other hand, it

may predispose to meconium aspiration syndrome by inducing

retching, vomiting and aspiration of gastric content while

inserting the feeding tube [28]. The incidence of meconium

aspiration syndrome, reported by four studies, was low

[5,8,9,13], which could be attributed to the inclusion of only

vigorous neonates with neonates at risk for meconium aspiration

syndrome, like those with low Apgar scores, respiratory

depression requiring resuscitation were excluded.

The limitation of the review was that data

for out-comes like meconium aspiration syndrome and adverse

events could not be pooled as the reported incidences were nil

in most of the studies. Proposed subgroup ana-lyses could not be

done due to the lack of data in the included trials.

Non-vigorous neonates requiring delivery room resuscitation were

excluded by all.

To conclude, low-quality evidence supported

the role of gastric lavage for the prevention of feeding

intolerance in vigorous late preterm and term neonates born

through meconium-stained amniotic fluid. Though the procedure

seems to be apparently safe, one should be cautious to recommend

this practice as the adverse events related to gastric lavage

were not evaluated critically and the effects of this procedure

on the routine newborn care practices such as skin-to-skin

contact, and breastfeeding rates were lacking. Evidence in

non-vigorous neonates, who are more prone for the development of

respiratory distress and feeding intolerance, were lacking.

Well-designed RCTs with defined outcome variables under strict

monitoring for procedure-related complications are needed.

Note: Additional material related

to this study is available with the online version at

www.indianpediatrics.net

Contributors: PS: conceptualized the

review, literature search, data analysis and manuscript writing;

MK: literature search, data analysis and manuscript writing; SB:

conceptualized the review, literature search, data analysis and

manuscript writing.

Funding: None; Competing interest:

None stated.

REFERENCES

1. Viraraghavan VR, Nangia S, Prathik BH,

et al. Yield of meconium in non-vigorous neonates undergoing

endotracheal suctioning and profile of all neonates born

through meconium-stained amniotic fluid: A prospective

observational study. Paediatr Int Child Health.

2018;38:266-70.

2. Chiruvolu A, Miklis KK, Chen E, Petrey

B, Desai S. Delivery room management of meconium-stained

newborns and respiratory support. Pediatrics.

2018;142:e20181485.

3. Narchi H, Kulaylat N. Feeding problems

with the first feed in neonates with meconium-stained

amniotic fluid. Paediatr Child Health. 1999;4:327 30.

4. Deshmukh M, Balasubramanian H, Rao S,

Patole S. Effect of gastric lavage on feeding in neonates

born through meconium-stained liquor: A systematic

review. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2015;100:F394-9.

5. Gidaganti S, Faridi MM, Narang M,

Batra P. Effect of gastric lavage on meconium aspiration

syndrome and feed intolerance in vigorous infants born with

meconium stained amniotic fluid - A randomized control

trial. Indian Pediatr. 2018;55:206-10.

6. Narchi H, Kulaylat N. Is gastric

lavage needed in neonates with meconium-stained amniotic

fluid? Eur J Pediatr. 1999;158:315-7.

7. Ameta G, Upadhyay A, Gothwal S, Singh

K, Dubey K, Gupta A. Role of gastric lavage in vigorous

neonates born with meconium stained amniotic fluid. Indian J

Pediatr. 2013;80:195 8.

8. Singh KB, Jain R, Babu R, Jyoti J,

Singh MK, Parasher I. Role of routine gastric lavage in term

and late preterm neonates born through meconium stained

amniotic: a randomised control trial. J Evol Med Dent Sci.

2013;2:9868-75.

9. Sharma P, Nangia S, Tiwari S, Goel A,

Singla B, Saili A. Gastric lavage for prevention of feeding

problems in neonates with meconium-stained amniotic fluid: A

randomised controlled trial. Paediatr Int Child Health.

2014;34:115 9.

10. Garg J, Masand R, Tomar BS. Utility

of gastric lavage in vigorous neonates delivered with

meconium stained liquor: a randomized controlled trial. Int

J Pediatr. 2014;2014:204807.

11. Shah L, Shah GS, Singh RR, Pokharel

H, Mishra OP. Status of gastric lavage in neonates born with

meconium stained amniotic fluid: A randomized controlled

trial. Ital J Pediatr. 2015;41:85.

12. Kumar A, Gupta RP, Singh A. Role of

gastric lavage in newborn with meconium stained amniotic

fluid: A randomized controlled trial. IOSR-JDMS.

2017;16:51-3.

13. Yadav SK, Venkatnarayan K, Adhikari

KM, Sinha R, Mathai SS. Gastric lavage in babies born

through meconium stained amniotic fluid in prevention of

early feed intolerance: A randomized controlled trial. J

Neonatal Perinatal Med. 2018;11:393 7.

14. Hutton EK, Thorpe J. Consequences of

meconium stained amniotic fluid: what does the evidence tell

us? Early Hum Dev. 2014;90:333 9.

15. Quandt D, Schraner T, Ulrich Bucher

H, ArlettazMieth R. Malposition of feeding tubes in

neonates: is it an issue? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr.

2009;48:608-11.

16. Shiao SY, Youngblut JM, Anderson GC,

DiFiore JM, Martin RJ. Nasogastric tube placement: Effects

on breathing and sucking in very-low-birth-weight infants. Nurs

Res. 1995;44:82 8.

17. Gasparella M, Schiavon G, Bordignon

L, et al. Iatrogenic traumas by nasogastric tube in very

premature infants: our cases and literature review. Pediatr

Med Chir. 2011;33:85 8.

18. Maruyama K, Shiojima T, Koizumi T.

Sonographic detection of a malpositioned feeding tube

causing esophageal perforation in a neonate. J Clin

Ultrasound. 2003;31:108 10.

19. Metheny NA, Meert KL, Clouse RE.

Complications related to feeding tube placement. Curr Op

Gastroenterol. 2007;23:178 82.

20. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J,

Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for

systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement.

PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097.

21. Fanaro S. Feeding intolerance in the

preterm infant. Early Hum Dev. 2013;89:S13-20.

22. Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et

al, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of

Interventions. 2nd ed. Chichester (UK): John Wiley & Sons,

2019.

23. Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer

program]. Version 5.4, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2020.

24. Schünemann H, Broek J, Guyatt G,

Oxman A, editors. GRADE handbook for grading quality of

evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October

2013. The GRADE working group, 2013.

25. Greenspan JS, Wolfson MR, Holt WJ,

Shaffer TH. Neonatal gastric intubation: differential

respiratory effects between naso-gastric and orogastric

tubes. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1990;8:254-8.

26. Widström AM, Ransjö-Arvidson AB,

Christensson K, Matthiesen AS, Winberg J, Uvnäs-Moberg K.

Gastric suction in healthy newborn infants. Effects on

circulation and developing feeding behaviour. Acta Paediatr

Scand. 1987;76:566-72.

27. Anand KJ, Runeson B, Jacobson B.

Gastric suction at birth associated with long-term risk for

functional intestinal disorders in later life. J Pediatr.

2004;144:449-54.

28. Khazardoost S, Hantoushzadeh S, Khooshideh M, Borna S.

Risk factors for meconium aspiration in meconium stained

amniotic fluid. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;27:577-9.

|

|

|

|

|