|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2021;58:951-954 |

|

Comparison of Clinical Features and Outcome

of Dengue Fever and Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in

Children Associated With COVID-19 (MIS-C)

|

|

Gurdeep Singh Dhooria, Shruti Kakkar, Puneet A Pooni, Deepak Bhat,

Siddharth Bhargava, Kamal Arora, Karambir Gill, Nancy Goel

From Department of Paediatrics, Dayanand Medical College and

Hospital, Ludhiana, Punjab.

Correspondence to: Dr Gurdeep Singh Dhooria, Professor, Department of

Pediatrics, Dayanand Medical College and Hospital, Ludhiana, Punjab.

Email:

[email protected]

Received: April 17, 2021;

Initial review: April 20,2021;

Accepted: July 20, 2021.

Published online: July 23, 2021;

PII:S097475591600355

|

Objective:

To identify clinical

and laboratory features that differentiate dengue fever patients from

MIS-C patients and determine their outcomes. Methods: This

comparative cross-sectional study was done at a tertiary care teaching

institute. We enrolled all hospitalized children aged 1 month - 18 years

and diagnosed with either MIS-C and/or dengue fever according to WHO

criteria between June and December, 2020. Clinical and laboratory

features and outcomes were recorded on a structured proforma.

Results: During the study period 34 cases of MIS-C and 83 cases of

Dengue fever were enrolled. Mean age of MIS-C cases (male, 86.3%) was

7.89 (4.61) years. MIS-C with shock was seen in 15 cases (44%), MIS-C

without shock in 17 cases (50%) and Kawasaki disease-like presentation

in 2 cases (6%). Patients of MIS-C were younger as compared to dengue

fever (P=0.002). Abdominal pain and erythematous rash were more

common in dengue fever. Of the inflammatory markers, mean C reactive

protein was higher in MIS-C patients [100.2 (85.1) vs 16.9 (29.3) mg/dL]

(P<0.001). In contrast, serum ferritin levels were higher in

dengue fever patients (P=0.03). Mean hospital stay (patient days)

was longer in MIS- C compared to dengue fever (8.6 vs 6.5 days; P=0.014).

Conclusions: Clinical and laboratory features can give important

clues to differentiate dengue fever and MIS-C and help initiate specific

treatment.

Keywords: Diagnosis, Evaluation, Inflammatory markers,

Management.

|

|

M

ultisystem

inflammatory syndrome in

children (MIS-C), an inflammatory condition following severe acute respiratory

syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has manifestations similar

to toxic shock syndrome or Kawasaki disease [1,2]. Dengue fever

can have clinical presentations similar to MIS-C with presence

of fever, erythematous rash, vomiting, abdominal pain and

develop- ment of shock in severe cases. Correct diagnosis and

appropriate management are critical to reduce mortality in both

the conditions.

We conducted this study to identify clinical

and laboratory features that differentiate dengue fever from

MIS-C patients admitted in a tertiary care center and determine

their outcomes.

METHODS

In this cross-sectional study, we evaluated

all hospitalized children aged 1 month to 18 years diagnosed

with MIS-C and/or dengue fever admitted in the department of

pediatrics, at our center from June to December, 2020. All

patient data were entered in a structured proforma. Patients

were followed up till discharge. Written informed consent was

taken from all participants and the study was approved by the

institutional ethics committee.

All patients with fever for more than three

days and fulfilling the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria

for MIS-C [1] were included. SARS-CoV-2 infection was diagnosed

by nasopharyngeal swab, real time reverse transcription

polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for SARS-CoV-2 infection

using TRUPCR SARS-CoV-2 (3B BLACK BIO, Kilpest India Ltd) and/or

rapid antibody test for SARS-CoV-2 (n=50) using Elevate

Anti-SARS-CoV-2 (IgG and IgM) (Roche Diagnostics GmbH).

Additionally, history of contact with a COVID-19 (coronavirus

disease 2019) positive patient was also considered positive as

per the WHO criteria.

Only confirmed case of dengue fever based on

serological evidence by IgM ELISA or by NS1 antigen positivity

were included. Patients with dengue infection were classified

into two groups viz., dengue with warning signs and severe

dengue, according to WHO classi-fication [5]. Dengue

antibody test for IgM detection was done using an IgM

antibody-capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (MAC-ELISA)

(PanBio, Standard Diagnostics Inc). Dengue NS1 antigen was

detected with the ELISA technique (J Mitra & Co Pvt Ltd).

Patients were serially monitored clinically

and by laboratory parameters and managed as per standard

guidelines. We collected demographic data; past medical history,

co-morbidities, clinical signs and symptoms, results of imaging,

cardiac, and laboratory testing for signs of inflammation

(elevated C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation

rate (ESR), fibrinogen, d-dimer, ferritin, lactic acid

dehydrogenase (LDH), or interleukin 6 (IL-6), elevated

neutrophils, reduced lymphocytes and low albumin) and organ

involvement, at presentation and throughout the hospital stay.

The information with respect to need for respiratory and

inotropic support, medications like steroids and intravenous

immune globulin (IVIG), duration of hospital stay and survival

was also collected. Clinical patterns of MIS-C patients

including those with or without shock and coronary involvement

were also noted. Left ventricle dysfunction was graded on

2D-echo as: normal function (EF

>55%), mild

dysfunction (EF 41-55%), moderate dysfunction (EF 31-40%), and

severe dysfunction (EF £30%)

[6]. The American Heart Association criteria for Kawasaki

disease were used [7].

To achieve a power of 80% and a level of

significance of 5% (two sided), for detecting a true difference

of 4 days (7.9-3.8 days) in mean duration of hospital stay

between MIS-C and dengue fever cases from previous studies [3,4]

assuming a pooled standard deviation of 5 days, minimum sample

size of 24 for each group was calculated.

Statistical analysis: Comparison of

quantitative variables was done using Student t-test and

Mann–Whitney U test for independent samples for

parametric and non-parametric data, respectively. For comparing

categorical data, chi-square test was used. Kaplan–Meier

analysis was used to estimate the duration of hospital stay in

the three groups, with the end point as time of discharge.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 24.0.

P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Of the 34 MIS-C cases, MIS-C with shock was

seen in 15 (44%) children, MIS-C without shock in 17 (50%)

children and Kawasaki like presentation in two children (6%). Of

the 83 cases of dengue fever, 51(61%) cases had severe dengue by

WHO classification. Mean (SD) age of children with dengue fever

was 10.07 (4.43) years compared to MIS-C, 7.18 (4.81) years (P=0.002).

MIS-C patients had more frequent symptoms of fever, conjunctival

injection, swelling of hand and feet, diarrhea and altered

sensorium. Whereas, abdominal pain and erythematous rash were

more commonly noted in dengue fever patients (Table I).

Clinical bleeding was seen only in dengue fever patients (7%).

Mean (SD) hematocrit was significantly higher in dengue fever

compared to MIS-C patients [38.6% (8.1%) vs. 29.1% (6.9%); P<0.001].

Mean platelet count and total leukocyte count was significantly

lower in dengue fever compared to MIS-C patients.

Table I Clinical Profile, Management and Outcome of Children With MIS-C and Dengue Fever

| Group |

MIS- C |

Dengue |

|

(n=34) |

(n=83) |

| Age a |

|

|

| 0-5 y |

12(35) |

12 (14) |

| 6-10 y |

16 (47) |

35 (42) |

| 11-18 y |

6 (18) |

36 (43) |

| Male gender |

28 (82) |

62 (75) |

| Signs/ symptoms |

|

|

|

Fever at admissionb |

34 (100) |

60 (72) |

| Diarrheaa |

4 (12) |

0 |

|

Abdominal painc |

12 (35) |

47 (57) |

| Vomiting |

17 (50) |

57 (69) |

|

Erythematous rashb |

9 (26) |

55 (66) |

|

Swelling of hand and feetb |

10 (29) |

0 |

| Respiratory distress |

14 (41) |

38 (46) |

|

Altered sensoriumc |

8 (24) |

6 (7) |

|

Conjunctival injectionb |

7 (21) |

0 |

| Myalgiab |

6 (18) |

68 (83) |

| Signs of capillary leak |

13 (38) |

36 (43) |

| Hypotension at admission |

15 (44) |

33 (39) |

| Imaging |

|

|

|

USG-moderate ascitis |

10 (59) |

15 (71) |

| X-ray pleural effusion |

10 (29) |

28 (34) |

|

LV dysfunctionb |

7 (21) |

0 |

| Management |

|

|

| Non-invasive ventilation |

6 (18) |

18 (22) |

|

Mechanical ventilationa |

6 (18) |

2 (2) |

| Inotropes |

13 (38) |

22 (27) |

|

Platelet transfusionc |

0 |

10 (12) |

| Patient outcome |

|

|

| PICU admission |

11 (32) |

21 (25) |

| Discharged |

31 (98) |

81 (98) |

|

All values in no. (%). MIS-C: multi-system inflammatory

syndrome in children associated with COVID-19; USG:

ultrasonography, IVIG: intravenous Immunoglobulin, LMWH

- low molecular weight heparin, PICU: pediatric

intensive care unit. Steroids, intravenous

immunoglobulin, low molecular weight heparin and aspirin

were used in 22, 11, 8 and 8 children with MIS-C and

none with dengue fever. aP<0.01; bP=0.001; cP<0.05. |

Of the inflammatory markers, mean CRP was

higher in MIS-C patients than dengue fever patients. Mean IL-6

levels, D-dimer and fibrinogen levels were also higher in MIS-C

patients. In contrast, mean serum ferritin levels were higher in

dengue fever patients. Left ventricular dysfunction was present

only in MIS-C patients (Table II and

Web Fig 1).

Need for mechanical ventilation was more in MIS-C cases as

compared to dengue fever cases. Intravenous immunoglobulin

(IVIG) infusion, steroids, low molecular weight heparin and

aspirin were used only in MIS-C cases (Table I).

Table II Laboratory Profile and Outcomes of Children With MIS-C and Dengue Fever

| Laboratory parameters |

MIS- C (n=34) |

Dengue (n=83) |

| Serum values |

|

|

| CRP (mg/L)a |

100 (85) |

17 (29) |

|

Ferritin (ng/mL)b |

2878 (5876) |

6136 (6600) |

|

D-Dimer (ng/mL)b

|

1619 (1313) |

733(291) |

|

Interleukin-6 ( pg/mL) |

677 (1505) |

11 (15) |

|

Fibrinogen (mg/dL)c

|

547 (98) |

238 (121) |

|

Hemoglobin (g/dL)a

|

9.7 (2.3) |

12.9 (2.7) |

| Leukocyte count (×109/L)a |

16.6 (12) |

7 (5.7) |

| Platelets (×109/L)a |

173.4 (134.7) |

48.1 (42) |

| AST (U/L) |

524 (1633) |

641 (1359) |

| ALT (U/L) |

236 (569) |

277 (531) |

|

Albumin (g/dL)b |

3 (1.1) |

3.5 (0.8) |

| LV ejection fraction (%) |

52 (13) |

60 (0) |

| PRISM II score |

9 (8) |

8 (6) |

| Hospital stay (d) |

8.1 (4.1) |

6.5 (3.3) |

|

Data prepented as mean (SD). MIS-C: Multi-system

inflammatory syndrome in children associated with

COVID-19; CRP-C-reactive protein; AST-aspartate

transaminase; ALT-alanine transaminase; LV: Left

ventricular;PRISM score II-Pediatric risk of mortality

score. aP<0.001;bP<0.05;cP<0.01. |

|

|

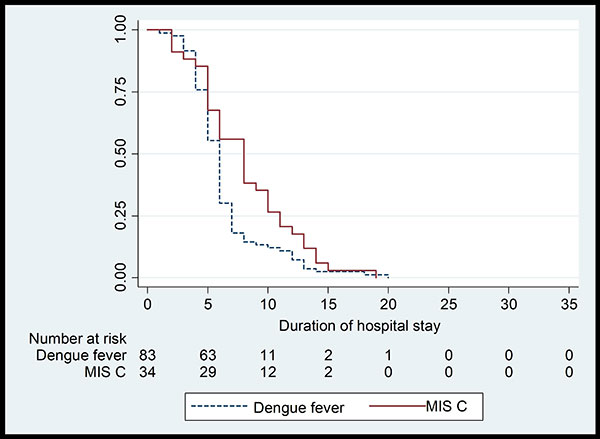

Fig. 1 Kaplan-Mayer graph

showing mean duration of hospital stay in children with

dengue fever and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in

children associated with COVID-19 (MIS-C).

|

Kaplan-Meier survival curve with discharge as

end point showed significantly longer duration of hospital stay

in MIS-C patients [8.58 days (95% CI 7.13 - 10.03)] compared to

dengue fever patients [6.54 days (95% CI: 5.78 - 7.21)] (P=0.014)

(Fig. 1).

Repeat 2D-echocardiography was done before

discharge in all patients with LV dysfunction/ Kawasaki disease

like presentation. Only two children (5.9%) showed cardiac

dysfunction, one case each with mild and moderate dysfunction.

Both the cases showed resolution during follow-up.

DISCUSSION

The study compares the clinical and

laboratory differences and outcomes of children hospitalized

with MIS-C and dengue fever. Patients with dengue fever were

significantly older as compared to MIS-C. Inflammatory marker

levels of CRP, IL-6, D dimer and fibrinogen were significantly

higher in MIS-C as compared to dengue fever patients.

All studies on MIS-C have reported

hyper-inflammatory state as a primary hallmark [8,9]. The

massive release of inflammatory mediators seen with exaggerated

activation of the immune system is similar to cytokine storm

syndrome [10]. It has been hypothesized that severe dengue is

also caused by a cytokine storm inducing systemic inflammatory

effects [11].

Although post-COVID MIS-C can present with

lower platelet counts but the severe thrombocytopenia (<50 x10 9/L)

as seen in dengue fever, is not common [8]. Also,

hemoconcentration is uncommon in MIS-C patients, making it an

important differentiating feature of dengue fever from MIS-C.

Leukopenia followed by thrombo-cytopenia, capillary leak and

hemoconcentration is very classic and pathognomonic of dengue

fever.

Cornelia, et al. [12] showed presence of

hyper-ferritinemia could discriminate between dengue and other

febrile diseases. Other dengue studies also found an association

between increased ferritin levels and severity of disease

[12,13]. We also found serum ferritin levels to be higher in

dengue fever patients than MIS-C patients.

In the present study, most patients requiring

invasive ventilation were in MIS-C group (18%) as compared to

dengue patients (2%). Other studies have also shown similar

results. [9,14].

The differentiation between dengue fever and

MIS-C is important in contemporary times because of entirely

different management strategy for the two conditions. Dengue

fever patients being managed with aggressive fluid management of

crystalloids and colloids with inotropic support and platelet

transfusions wherever needed. On the other, such aggressive

fluid management in MIS-C patients would be detrimental in

patients with cardiac dysfunction that is often present in MIS-C

patients with shock. Moreover, vital role of intravenous

immuno-globulin and steroids in management of MIS-C patients can

never be overemphasized.

The study has few limitations. Firstly, the

study is an experience from a single center. The diagnosis of

dengue fever was based on serology in one third of cases.

Studies have shown that COVID-19 cases may be misdiagnosed as

dengue fever when relying on DENV IgM, which can remain positive

months after COVID-19 infection [15].

To conclude, the presence of conjunctival

injection, swelling of hand and feet, diarrhea, and altered

sensorium in a febrile child with laboratory evidence of

hyper-inflammation (highly raised CRP, leukocytosis, raised D-

dimers are pointers more in favor of MIS-C. Whereas, vomiting,

myalgia and erythematous rash along with hyperferritinemia,

hemoconcentration, leukopenia and severe thrombocytopenia are

more common in dengue fever patients.

Acknowledgements: Namita Bansal,

Statistician for analyzing the data and for preparation of

tables and graphs. Dr Jatinder Goraya for his advice and

support.

Note: Additional material related

to this study is available with the online version at

www.indianpediatrics.net

Ethics clearance: Institutional ethics

committee; No: DMCH/R&D/2020/168 dated November 09, 2020.

Contributors: GSD, PAP: conceived

and designed the study: SK, NG, KG: recruited the subjects,

collected the data; KA, SB, GSD: literature review, initial

draft of manuscript; PAP, DB, GSD: contributed to manuscript

writing; and PAP, DB, GSD: finalized the manuscript. All authors

approved the manuscript submitted.

Funding: None; Competing interests:

None stated.

|

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS?

• We provide clinical and laboratory indicators that

can give clues to differentiate dengue fever from MIS-C

patients.

|

REFERENCES

1. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in

children and adolescents with COVID-19. Scientific brief:

World Health Organization. 15 May 2020. Accessed April 15,

2021. Available from: https:

//www.who.int/publications-detail/multisysteminflammatory-syndrome-in-children-andadole

scents-with-covid19

2. Alsaied T, Tremoulet AH, Burns JC, et

al. Review of cardiac involvement in multisystem

inflammatory syndrome in children. Circulation.

2021;143:78-88.

3. Ahmed M, Advani S, Moreira A, et al.

Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children: A systematic

review. E Clin Med. 2020;26:100527.

4. Mishra S, Ramanathan R, Agarwalla SK.

Clinical profile of dengue fever in children: A study from

southern Odisha, India. Scientifica (Cairo).

2016;2016:6391594.

5. World Health Organization. Dengue

Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, prevention and control:

New edition 2009. Accessed April 15, 2021. Available from:

https://www. who.int/rpc/guidelines/9789241547871/en/

6. Tissot C, Singh Y, Sekarski N.

Echocardiographic evaluation of ventricular function-for the

neonatologist and pediatric intensivist. Front Pediatr.

2018;6:79.

7. McCrindle BW, Rowley AH, Newburger JW,

et al; American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever,

Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee of the Council

on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; Diagnosis,

Treatment, and Long-Term Management of Kawasaki Disease: A

Scientific Statement for Health Professionals From the

American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135:e927-e999.

8. Feldstein LR, Rose EB, Horwitz SM, et

al. Overcoming COVID-19 Investigators; CDC COVID-19 response

team. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in U.S. children and

adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2020;23:334-46.

9. Rowley AH. Understanding

SARS-CoV-2-related multi-system inflammatory syndrome in

children. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:453-54.

10. Alunno A, Carubbi F, Rodríguez-Carrio

J. Storm, typhoon, cyclone or hurricane in patients with

COVID-19 ? Beware of the same storm that has a different

origin. RMD Open. 2020;6:e001295.

11. Srikiatkhachorn A, Mathew A, Rothman

AL. Immune-mediated cytokine storm and its role in severe

dengue. SeminImmunopathol. 2017;39:563-74.

12. van de Weg CA, Huits RM, Pannuti CS,

et al. Hyperferritinaemia in dengue virus infected patients

is associated with immune activation and coagulation

disturbances. PLoSNegl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e3214.

13. Chaiyaratana W, Chuansumrit A,

Atamasirikul K, Tangnararatchakit K. Serum ferritin levels

in children with dengue infection. Southeast Asian J Trop

Med Public Health. 2008;39:832-36.

14. Jain S, Sen S, Lakshmivenkateshiah S,

et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children with

COVID-19 in Mumbai, India. Indian Pediatr. 2020;57:1015-19.

15. Lokida D, Lukman N, Salim G, et al. Diagnosis of COVID-19

in a dengue-endemic area. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;103:1220-22.

|

|

|

|

|