Mortality

in children with epilepsy is significantly higher than the

general population [1]; although, most deaths in children with

epilepsy are not related to seizures or epilepsy [2]. The higher

risk is explained by several factors: respiratory illness with

underlying neurological condition that presents with seizures,

systemic comorbidities, indirect factors as well as deaths

presumably or demonstrably due to seizures. Sudden unexpected

death in epilepsy (SUDEP), which belongs to the last group, has

gained prominence as a cause of death in epilepsy in recent

years.

DEFINITION

SUDEP is

defined as a “sudden unexpected witnessed or unwitnessed,

non-traumatic, non-drowning death in a patient with epilepsy

with or without evidence of a seizure and excluding documented

status epilepticus in which post-mortem examination does not

reveal a toxicological or anatomical cause of death [3].’’ This

definition requires a postmortem examination to diagnose SUDEP,

which is not available in the majority of instances. Hence,

criteria have been described for definite, probable and possible

SUDEP [4] (Box I).

|

Box I Classification and Definition of Subtypes

of Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy (SUDEP) |

Definite SUDEP

• Sudden, unexpected, witnessed

or unwitnessed, non-traumatic and non-drowning death,

occurring in benign circumstances, in an individual with

epilepsy, with or without evidence for a seizure, and

excluding documented status epilepticus in which

postmortem examination does not reveal a cause of death.

Probable SUDEP

• Same as definite SUDEP

but without autopsy. The victim should have died

unexpectedly while in a reasonable state of health,

during normal activities, and in benign circumstances,

without a known structural cause of death.

Possible SUDEP

• SUDEP cannot be ruled out but a

competing cause of death is present. If a death is

witnessed, a cutoff of death within one hour from acute

collapse is suggested.

|

BURDEN

The incidence

rates of SUDEP in children have been reported to be 0.36-0.43

per 1000 person-years [5-7]. Although SUDEP rates have been

reported to be lower in children compared to adults, the

American Academy of Neurology (AAN) practice guidelines on SUDEP

established the incidence rate of SUDEP in children with

epilepsy to be 0.22/1000 patient–years (95% CI 0.16-0.31) after

a systematic review of 12 class I studies [8]. Due to

imprecision in incidence data results, random-effect

meta-analysis was further performed. SUDEP was found to affect 1

in 4,500 children with epilepsy in one year, making the risk of

SUDEP rare.

Risk

Predictors

There are very

few studies assessing risk factors in childhood SUDEP and most

of the data is derived from larger studies in adults.

•

The presence

and frequency of generalized tonic-clonic seizures (GTCS) is an

important risk predictor for SUDEP [8].

•

The relative

risk of SUDEP is 7.7 times higher in patients with onset of

epilepsy between 0-15 years compared to onset after the age of

45 years [9].

•

All-cause

mortality, including SUDEP, is also higher in children with

developmental delay [10].

•

Children

with uncontrolled seizures have a higher risk [11].

•

SUDEP has

also been shown to increase with the duration and severity of

seizures, with 15-fold risk with more than 50 GTCS per year,

nocturnal seizures and the occurrence of GTCS [12], as well as

prolonged tonic state leading to post-ictal immobility [13].

•

Postictal

generalized EEG suppression beyond 50 seconds also may have a

predictive role in SUDEP and is associated with sleep, shorter

duration of clonic phase, symmetric tonic extension posturing

and terminal burst-suppression after a seizure [14].

•

Symptomatic

epilepsy has a higher risk of SUDEP compared to idiopathic

generalized epilepsy.

Patients with Dravet syndrome are also at a higher risk

of death [15].

SUDEP shares certain features

with the syndrome of sudden infant death (SIDS), suggesting

possible common mechanisms. SIDS is sudden and unexpected death

that occurs in infants below the age of one year. Both SIDS and

SUDEP are diagnoses of exclusion, and autopsy findings are

usually not revelatory. Deficiency in arousal response to rise

in carbon dioxide in both syndromes may contribute to death,

suggesting that these two entities may lie on a continuum [16].

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The

pathophysiology of SUDEP is not well elucidated and is believed

to arise from an interaction between predisposing factors and

triggers. Predisposing factors include effects of long-standing

seizure disorder such as altered autonomic function, etiology of

epilepsy (e.g. symptomatic, familial), factors related to

drug therapy such as abrupt withdrawal or polypharmacy etc.

A triggering seizure leads to preterminal events including

cardiac, respiratory, autonomic and cerebral dysfunction. The

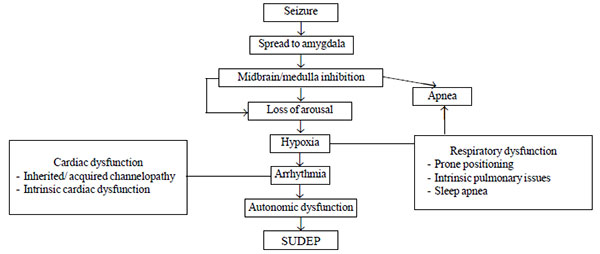

various mechanisms (Fig. 1) include the following:

Cardiac dysfunction:

Sudden cardiac arrest is a proposed mechanism with certain ion

channel abnormalities being implicated in both epilepsy and

cardiac arrhythmia. The most widely implicated is the sodium

channel abnor-mality, which may also explain the higher rates of

SUDEP in Dravet syndrome [17]. Another link is the association

between long QT syndrome and familial epilepsies, both of which

are channelopathies.

|

| Fig. 1 Various pathophysiological

mechanisms leading to sudden unexpected death in

epilepsy (SUDEP). |

Respiratory dysfunction:

Severe peri-ictal hypoxia occurs in one-fourth of patients with

SUDEP [17]. Autopsy changes of pulmonary edema have also been

observed in SUDEP cases, but this is likely an effect than a

cause of SUDEP.

Autonomic dysfunction:

Various autonomic abnor-malities have been described in patients

with refractory epilepsy and include lower parasympathetic and

higher sympathetic tone, increased vasomotor tone and impaired

heart rate variability [18]. Changes in ictal heart rate also

suggest autonomic dysfunction, with tachycardia occur-ring in up

to 60% of seizures and bradycardia in 6% of focal seizures

[17,19]. As per the Mortality in epilepsy monitoring units study

(MORTEMUS), an initiative that assessed cases of SUDEP and

near-SUDEP in patients admitted for video-EEG monitoring,

post-ictal centrally mediated cardiac and respiratory depression

associated with post-ictal generalized EEG suppression was a

strong mechanism leading to SUDEP [20]. The switch from

parasympathetic to sympathetic state, combined with sympathetic

over-drive that accompanies the state of drug withdrawal that

accompany seizures may be a possible precipitant.

Channelopathies:

Channelopathies are disorders characterised by dysfunction of

ion channels. Traditio-nally channelopathies have been

considered genetic defects eg., long QT syndrome and

Dravet syndrome. In inherited channelopathies, the same ion

channel abnormalities are expressed in the heart as well as the

brain. Hence, these epilepsies are associated with an

arrythmia-prone cardiac condition.

Recently,

there is an emerging concept of acquired channelopathy i.e.,

channel dysfunction in patients with chronic epilepsy. Animal

studies have shown that epilepsy alters the expression of

sodium, potassium, calcium and cationic channels in the heart.

In these acquired cardiac channelopathies, epilepsy increases

the pro-arrhythmic state increasing predisposition to sudden

death [21].

Cerebral dysfunction:

SUDEP occurs more often in sleep and almost all cases are

nocturnal and associated with the prone position. Various

neurotransmitter abnormalities have been reported in association

with SUDEP including low serotonin state [22] and excessive

opioid [23] and adenosine activity. Brainstem serotonin

modulates respiratory drive and has also been implicated in

sudden infant death syndrome [24]. It may contribute to SUDEP by

a similar mechanism.

INTERVENTIONS FOR PREVENTION

As

uncontrolled epilepsy is a known risk factor, effective epilepsy

treatment to reduce frequency and duration of seizures as well

as GTCS should be targeted. Nocturnal supervision was found to

be protective in one case-control study [25] and may be combined

with seizure detection devices, but clinching evidence in SUDEP

prevention is lacking. It is of potential benefit in children

with uncontrolled or nocturnal seizures. In India, nocturnal

supervision of children is generally culturally acceptable as

co-sleeping of children with their parents is common. A blanket

‘back to sleep’ advice to avoid prone positioning may be

recommended, with the caveat that it is the post-ictal turning

prone which is usually responsible. Hence parents should be

counseled to turn the child to a lateral position and avoid

prone position after the seizure. The use of lattice or safety

pillows may reduce the contribution of prone position to

post-ictal cardiorespiratory distress.

In terms

of preventive drug therapy, it has been observed in mouse models

of SUDEP that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI)

such as fluoxetine may decrease apnea risk [26]. Serotonergic

neurons in the brainstem are believed to be responsive to rise

in CO2 and fall in pH levels in

the blood and thereby stimulate respiration and arousal. In a

retrospective study on adults with focal seizures [27], it was

noted that patients on SSRIs (for co-morbid mental health

problems) had a reduced likelihood of post-ictal oxygen

desaturation as compared to patients who were not on SSRIs.

Recently, two randomized controlled trials have been completed

to evaluate the role of fluoxetine to prevent post-seizure

apneas and desaturation; however, the results have not been

published yet. Massive release of endogenous opioids and

adenosine is induced by seizures and helps in seizure

termination [28]. However, this surge can also lead to

post-ictal apnea. Naloxone is currently under a randomized trial

for this purpose. Adenosine antagonists may also be beneficial

for this purpose.

These therapies; however, are

still in the emerging phase and currently being tried in adults.

More evidence is needed before the data can be extrapolated to

children.

Parental

Counseling

Counseling of

caregivers and sensitization towards SUDEP is imperative.

Caretakers should be educated regarding the importance of

adherence to treatment, nocturnal supervision, especially to

avoid prone position after seizures, as well as basic life

support training imparted to willing caregivers. However,

whether all patients with epilepsy should be counseled about the

risk of SUDEP or only high-risk patients remains a matter of

debate, and scientific data till date does not permit the

establishment of evidence-based guidelines for the same.

However, disclosure of SUDEP risk to all epilepsy patients has

been endorsed by multiple neurological societies, including a

joint task force of the American Epilepsy Society and the

Epilepsy Foundation and the American Academy of Neurology (AAN)

[29], and in India by the joint consensus document on parental

counseling by Association of Child Neurology (AOCN) and Indian

Epilepsy Society (IES) [30]. In a study on parental views

regarding the counseling of SUDEP risk, parents generally

expressed a preference for receiving routine SUDEP counseling at

the time of the diagnosis of epilepsy [31]. In another study

from Malaysia (32% of participants were of Indian origin), 70.9%

of parents felt that receiving SUDEP information was positive

[32]. Most parents did not report any impact on their own

functioning. However, increasing numbers over time reported an

impact on the child’s functioning. In a study from UK, 74% of

pediatric neurologists conveyed SUDEP information to a select

group of patients only. In contrast, 94% of parents of children

with epilepsy expected the physician to provide SUDEP

information [33].

In India, many neurologists and

pediatricians feel that imparting the knowledge of SUDEP may

increase parental anxiety and stress levels, which may be

unwarranted as the complication is so rare. However, it is also

known that many parents are afraid their child would die when

they witness the child having a seizure for the first time. The

information that the risk of death is very low may be

reassuring. Also, the knowledge of this condition may improve

drug compliance, as seen in studies from outside India. In an

Indian study of SUDEP counseling of adults with epilepsy and

their caregivers, it was shown to increase drug adherence

without any increase in anxiety or stress levels in either the

patients or their caregivers [34]. More experience is needed in

this field to understand parental perceptions and reactions.

CONCLUSION

SUDEP is an

under-recognized but important threat in patients with epilepsy.

It is important to assess SUDEP risk in all epilepsy patients,

particularly in those with generalized tonic-clonic convulsions,

nocturnal seizures, as well as co-morbid developmental delay.

Appropriate antiepileptic drug therapy with stress on

compliance, early surgical referral for surgically remediable

epilepsies, avoiding post-seizure prone positioning, and

caretaker counseling and support will go a long way in the

prevention of this condition.

Contributors:

DG performed the literature review and wrote the first draft

which was critically revised by SS. Both authors approved the

final version of the submitted manuscript.

Funding:

None;

Competing interest: None stated.

REFERENCES

1. Appleton R. Mortality in

paediatric epilepsy. Arch Dis Child. 2003;1091-4.

2. Gaitatzis A, Johnson AL,

Chadwick DW, Shorvon SD, Sander JW. Life expectancy in people

with newly diagnosed epilepsy. Brain. 2004;127:2427-32.

3. Nashef L. Sudden

unexpected death in epilepsy: Terminology and definitions.

Epilepsia. 1997;38:S6-8.

4. Nashef L, E. So P.

Ryvlin T. Tomson. Unifying the definitions of sudden unexpected

death in epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2012;53:227-33.

5. Sillanpää M, Shinnar S.

Long-term mortality in childhood-onset epilepsy. N Engl J Med.

2010;363:2522-9.

6. Weber P, Bubl R,

Blauenstein U, Tillmann BU, Lütschg J. Sudden unexplained death

in children with epilepsy: A cohort study with an eighteen-year

follow-up. Acta Paediatr. 2005;94:564-7.

7. Sillanpää M, Shinnar S.

SUDEP and other causes of mortality in childhood-onset epilepsy.

Epilepsy Behav. 2013;28:249-55.

8. Harden C, Tomson T,

Gloss D, Buchhalter J, Cross JH, Donner E, et al.

Practice Guideline Summary: Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy

Incidence Rates and Risk Factors. Report of the Guideline

Development, Dissemi-nation, and Implementation Subcommittee of

the American Academy of Neurology and the American Epilepsy

Society. Neurology. 2017;88:1674-80.

9. Berg AT, Nickels K,

Wirrell EC, Geerts AT, Callenbach PM, Arts WF, et al.

Mortality risks in new-onset childhood epilepsy. Pediatrics.

2013;132:124-31.

10. Shinnar S, Pellock JM.

Update on the epidemiology and prognosis of pediatric epilepsy.

J Child Neurol. 2002; 17: S4-S17.

11. Nickels KC, Grossardt

BR, Wirrell EC. Epilepsy-related mortality is low in children: A

30-year population-based study in Olmsted County, MN. Epilepsia.

2012;53:2164-71.

12. Hesdorffer DC, Tomson

T, Benn E, Sander JW, Nilsson L, Langan Y, et al.

Combined analysis of risk factors for SUDEP. Epilepsia.

2011;52:1150-9.

13. Tao JX, Yung I, Lee A,

Rose S, Jacobsen J, Ebersole JS. Tonic phase of a generalized

convulsive seizure is an independent predictor of postictal

generalized EEG suppression. Epilepsia. 2013;54:858-65.

14. Lamberts RJ, Gaitatzis

A, Sander JW, Elger CE, Surges R, Thijs RD. Postictal

generalized EEG suppression: An inconsistent finding in people

with multiple seizures. Neurology. 2013; 81:1252-6.

15. Skluzacek JV, Watts KP,

Parsy O, Wical B, Camfield P. Dravet syndrome and parent

associations: The IDEA League experience with comorbid

conditions, mortality, management, adaptation, and grief.

Epilepsia. 2011;52:95-101.

16. Buchanan GF. Impaired

CO2-induced

arousal in SIDS and SUDEP. Trend Neurosci. 2019:42:242-50.

17. Moseley BD, Wirrell EC,

Nickels K, Johnson JN, Ackerman MJ, Britton J.

Electrocardiographic and oximetric changes during partial

complex and generalized seizures. Epilepsy Res. 2011;95:237-45.

18. Mukherjee S, Tripathi

M, Chandra PS, Yadav R, Choudhary N, Sagar R, et al.

Cardiovascular autonomic functions in well-controlled and

intractable partial epilepsies. Epilepsy Res. 2009;85:261-9.

19. Zijlmans M, Flanagan D,

Gotman J. Heart rate changes and ECG abnormalities during

epileptic seizures: Prevalence and definition of an objective

clinical sign. Epilepsia. 2002;43:847-54.

20. Ryvlin P, Nashef L,

Lhatoo SD, Bateman LM, Bird J, Bleasel A, et al.

Incidence and mechanisms of cardio-respiratory arrests in

epilepsy monitoring units (MORTEMUS): A retrospective study.

Lancet Neurol.

2013;12:966-77.

21. Li MCH, O’Brien

TJ,Todaro M, Powell KL. Acquired cardiac channelopathies in

epilepsy: Evidence, mechanisms and clinical significance.

Epilepsia. 2019:60: 1753-67.

22. Toczek MT, Carson RE,

Lang L, Ma Y, Spanaki MV, Der MG, et al. PET imaging of

5HT1A receptor binding in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy.

Neurology. 2003;60:749-56.

23. Tortella FC, Long JB,

Holaday JW. Endogenous opiate systems: Physiological role in the

self-limitation of seizures. Brain Res. 1985;332:174-8.

24. Paterson DS,

Trachtenberg FL, Thompson EG, Belliveau RA, Beggs AH, Darnall R,

et al. Multiple serotonergic abnormalities in sudden

infant death syndrome. JAMA. 2006;296:254-32.

25. Langan Y, Nashef L,

Sander JW. Case-control study of SUDEP. Neurology.

2005;64;1131-3.

26. Faingold CL, Tupal S,

Randall M. Prevention of seizure-induced sudden death in a

chronic SUDEP model by semichronic administration of a selective

serotonin reuptake inhibitor. Epilepsy Beh. 2011;22:186-90.

27. Bateman LM, Li CS, Lin

TC, Seyal M. Serotonin reuptake inhibitors are associated with

reduced severity of ictal hypoxemia in medically refractory

partial epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2010;51:2211-4.

28. Volpicelli JR, Alterman

AI, Hayashida M, O’Brien CP. Naltrexone in the treatment of

alcohol dependence. Arch Gen Psych. 1992;49:876-80.

29. Maguire MJ, Jackson CF,

Marson AG, Nolan SJ. Treatments for the prevention of sudden

unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP). Cochrane Database Syst

Rev. 2016;7:CD011792.

30. Srivastava K, Sehgal R,

Konanki R, Jain R, Sharma S, Mittal R. Association of Child

Neurology-Indian Epilepsy Society Consensus Document on Parental

Counseling of Children with Epilepsy. Indian J Pediatr.

2019;86:608-16.

31. Ramachandrannair R,

Jack SM, Meaney BF, Ronen GM. SUDEP: What do parents want to

know? Epilepsy Beh. 2013;29:560-4.

32. Fong CY, Lim WK, Kong

AN, Lua PL, Ong LC. Provision of sudden unexpected death in

epilepsy (SUDEP) information among Malaysian parents of children

with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2017;75:6-12.

33. Gayatri NA, Morrall MC,

Jain V, Kashyape P, Pysden K, Ferrie C. Parental beliefs

regarding the provision and content of written sudden unexpected

death in epilepsy (SUDEP) information. Epilepsia.

2010;51:777-82.

34. Radhakrishnan DM,

Ramanujam B, Srivastava P, Dash D, Tripathi M. Effect of

providing sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP)

information to persons with epilepsy (PWE) and their caregivers

experience from a tertiary care hospital. Acta Neurol Scand.

2018;138:417-24.