|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2019;56: 885-887 |

|

Investigating the Muzaffarpur Outbreaks in the Backdrop of

Western Uttar Pradesh Experience: The Way Forward

|

|

Vipin M Vashishtha

Director and Consultant Pediatrician, Mangla Hospital

and Research Center, Shakti Chowk, Bijnor, Uttar Pradesh, India.

Email:

vipinipsita@gmail.com

|

|

The death of more than 130 children in Muzaffarpur, Bihar during the

summer months of 2019 due to Acute encephalitis syndrome (AES) has

raised an intense debate on the probable etiology of the killer disease.

The recurrent outbreaks of the disease are reported since 1995, and

several attempts have already been made by the different teams to clinch

the exact etiology [1,2]. The key recent investigations were performed

by three sets of expert-groups – John, et al. [3], the Natioal

Center for Disease Control (NCDC), India, and Centre for Disease Control

(CDC), United State (US) group [4], and by the pediatrician

in-charge of Shri Krishna Medical College Hospital (SKMCH), Muzaffarpur

[5]. While the first two groups identified litchi toxins, namely

methylene cyclopropylglycine (MCPG) and methylene cyclopropy-lalanine

(MCPA or hypoglycin A), responsible for the development of an acute

hypoglycemic encephalopathy (AHE) amongst malnourished, poor, rural

children [3,4], the latter suggested extremely high environmental

temperature and humidity in the region resulting in ‘heat stroke’ that

led to encephalopathy [5]. Due to the lack of documented hyperpyrexia in

all the cases, and early morning onset of symptoms, there were few

takers for the heat stroke theory. The litchi-toxins theory was more

acceptable and the Bihar State Health Ministry started following the

preventive measures as suggested by the groups who put forward this

theory. The number of cases and deaths declined sharply in the following

four years, 2015 to 2018 only to resurface in a much significant number

in 2019.

A previous similar recurrent epidemic in many

districts of Western Uttar Pradesh (UP), the so-called ‘Saharanpur

encephalitis’ [6], was investigated by an independent group of

investigators and the etiology was identified as toxicity due to oral

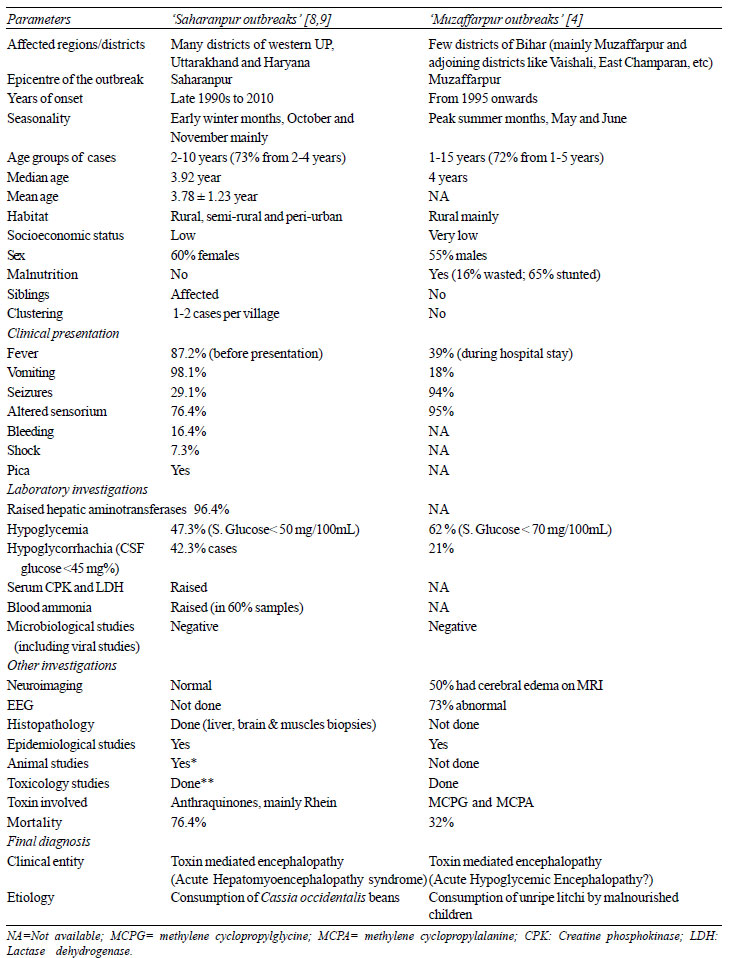

ingestion of a local weed [7]. There are many similarities between the

western UP and Muzaffarpur outbreaks; yet the approach, investigations

and the outcomes are quite different (Table I).

|

TABLE I Comparative Analysis of

Investigations of Western UP Aka ‘Saharanpur’ and ‘Muzaffarpur’

Outbreaks

|

|

In the Western UP outbreak, step-wise investigation

approach was adopted and as a first step a proper ‘case definition’ with

exclusion and inclusion criteria was formed. Based on its strict

application, the disease was initially identified as an encephalopathy

[6]. The next step was the histopathological examination of few target

organs, which hinted toward toxin-mediated necrosis of liver and muscles

(thus the term (acute hepato-myoencephalopathy (HME) syndrome) [6,7].

The differences in approaches in the two outbreak investi-gations are

presented in (Table I).

With the re-emergence of the outbreak in Muzaffarpur

this year, the debate on the exact etiology has reignited. While the

role of any microbiological agent as the main trigger has been abandoned

by most investigators, the focus is now on the litchi toxins and heat

stroke as probable theories. Despite many ‘missing links’ like

inconsistent findings of hypoglycemia and hyperthermia, lack of profuse

vomiting (a hallmark of MCPA toxicity), ‘mismatched’ seasonality

(paucity of unripe fruits at the peak of the outbreaks when the entire

crop is matured), no clarity on toxic levels (LD50) of toxins that cause

dose-dependent toxicity, occurrence in children too young to eat the

fruit, lack of hepatic dysfunctions despite mitochondrial involvement,

flawed selection of controls in case-control study, lack of study of

toxins in the body fluids of healthy siblings and peers living in the

same household or village, the doubtful role of rapid correction of

hypoglycemia on prevention of deaths, the litchi toxin theory was

considered as the most plausible one.

A detailed case-control study in western UP helped in

identifying the putative toxin which turned out to be anthraquinone

derivatives contained in the beans of the weed, Cassia occidentalis

[7]. Previous published literature confirmed the biological

plausibility of causation in vertebrates. The cause-effect relationship

of the Cassia occidentalis with acute HME syndrome in Wistar rats

was subsequently demonstrated [8]. These detailed studies also helped in

further outbreaks like the one in Sylhet, Bangladesh (2007-08) [9] and

another in Malkangiri, Orissa (2016).

Currently, the outbreak investigations in India are

at the crossroads. The need is to conduct investigations which

are detailed and comprehensive, and performed in a coordinated and

step-wise manner without any fixed notion.

References

1. Yewale VN. Misery of mystery of Muzaffarpur.

Indian Pediatr. 2014;51:605-6.

2. Vashishtha VM. Encephalitis outbreaks in

Muzaffarpur: Five blind men describing an elephant! Indian Pediatr.

2014; 51:936.

3. John TJ, Das M. Acute encephalitis syndrome in

children in Muzaffarpur: hypothesis of toxic origin. Curr Sci

2014;106:1184-5.

4. Shrivastava A, Kumar A, Thomas JD, Laserson KF,

Bhushan G, Carter MD, et al. Association of acute toxic

encephalopathy with litchi consumption in an outbreak in Muzaffarpur,

India, 2014: A case-control study. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5:e458-e466.

5. Sahni GS. Recurring epidemics of acute

encephalopathy in children in Muzaffarpur, Bihar. Indian Pediatr

2012;49:502-03.

6. Vashishtha VM, Nayak NC, John TJ, Kumar A.

Recurrent annual outbreaks of a hepato-myo-encephalopathy syndrome in

children in western Uttar Pradesh, India. Indian J Med Res. 2007;125:523-33.

7. Vashishtha VM, Kumar A, John TJ, Nayak NC.

Cassia occidentalis poisoning causes fatal coma in children in

western Uttar Pradesh. Indian Pediatr 2007; 44:522-5.

8. Panigrahi G, Tiwari S, Ansari KM, Chaturvedi RK,

Khanna VK, Chaudhari BP, et al. Association between children

death and consumption of Cassia occidentalis seeds: clinical and

experimental investigations. Food Chem Toxicol. 2014;67:236-48.

9. Gurley ES, Rahman M, Hossain MJ, Nahar N, Faiz MA,

Islam N, et al. Fatal outbreak from consuming Xanthium strumarium

seedlings during time of food scarcity in northeastern Bangladesh. PLoS

One. 2010;5:e9756.

|

|

|

|

|