|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2019;56:

873-875 |

|

School-age Children as Asymptomatic Malaria Reservoir in

Tribal Villages of Bastar Region, Chhattisgarh

|

|

R Ranjha 1*,

GDP Dutta1 and SV

Gitte2

From 1ICMR-National Institute of

Malaria Research,

FU-Raipur; and 2Regional Office of Health and Family Welfare and

Regional Leprosy training and Research Institute, Raipur; Chhattisgarh,

India.

*[email protected]

|

|

Malaria is a major health concern in India, especially in regions

populated by tribals. In this cross-sectional survey carried out in

Bastar region of Chhattisgarh, 35 Plasmodium infections were detected in

451 participants screened during the non-transmission season; 27 (77.1%)

were asymptomatic. Participants with age 6-14 years were at high risk of

asymptomatic infection [OR 4.09, 95% CI, 1.69 to 9.89, P=0.001],

and may act as an under-appreciated reservoir for sustained malaria

transmission.

Keywords: Control,

Diagnosis, Plasmodium, Management, Transmission.

|

|

I

ndia has a target of malaria elimination by 2030.

Controlling and elimination of malaria from tribal communities is a

major task and need more attention to achieve the target of malaria

elimination [1]. Tribal populations are reported to have naturally

acquired immunity to malaria [2]. Due to this immunity, individuals do

not develop clinical symptoms and do not seek medical treatment.

School-age children and adults that are not the main focus of malaria

prevention strategies may act as reservoirs for malaria transmission due

to the naturally acquired immunity [3]. Tribals constitute more than 30%

of the total population of Chhattisgarh. To control and eliminate

malaria from Chhattisgarh it will be important to identify the potential

reservoir for malaria transmission. This study was undertaken to find

out the reservoir of asymptomatic malaria in the tribal population of

Bastar region, Chhattisgarh, just before the transmission season in July

2017.

The study was carried out in the Keshkal block,

Kondagaon district, Bastar division, Chhattisgarh. Using Epiinfo 7

software, a sample size of 422 was calculated with expected frequency 7%

[5], design effect 1.5 and 99.9% confidence interval. Five villages were

randomly selected for the survey out of 101 villages in the block.

Households from these villages were selected using systematic sampling,

and blood sample was collected from every member of household who was

eligible and had given consent. Blood samples were collected from 451

participants. Written informed consent was obtained from all the

participants and the guardian of minors participating in the study. This

study was approved by the institutional ethics committee, ICMR-National

Institute of Malaria Research.

A short clinical assessment of all the study

participants was done and information related to malaria-related

symptoms (fever, headache, vomiting, and nausea) was recorded. Malaria

diagnosis was performed using microscopy. Blood slides were stained with

JSB stain and examined under compound microscope (Carl Zeiss Oberkochen,

Germany) at 100X magnification for malaria parasite detection. Diagnosis

was done by two trained laboratory technicians. Both thick and thin

smears were made on the microscopic slides. Thick smears were used for

parasite detection and thin smears were used for species identification.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 20.0 (Armonk, New

York, USA) and GraphPad Prism software (La Jolla, CA 92037 USA). Student

t-test and chi-square test were used. P-value <0.05 was considered as

significant.

TABLE I Age- and Gender-wise Distribution of Study Participants

|

Variable |

Total participants |

Malaria negative |

Asymptomatic malaria

|

Symptomatic malaria

|

|

(n=451) |

(n=416) |

positive (n=27) |

positive (n=8) |

|

Male sex, n (%) |

174 (38.6) |

158 (38.0) |

13 (48.1) |

3 (37.5)

|

|

Age (y)* |

23.4 (16.7)

|

24.0 (16.8)

|

13.4 (8.9)

|

23.6 (19.7)

|

|

Age distribution, n (%) |

|

6 mo-5 y |

26 (5.8) |

24 (5.8) |

2 (7.4) |

0 |

|

6-14 y |

75 (16.6) |

53 (12.7) |

18 (66.7) |

4 (50) |

|

³15 y |

350 (77.6) |

339 (81.5) |

7 (25.9) |

4 (50) |

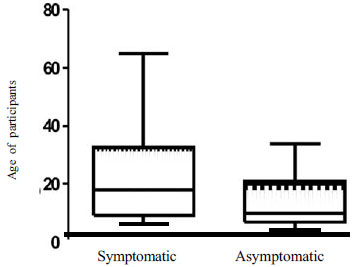

Mean age (range) of participants was 19 (1-71) years

(61.8% females) (Table I). A total of 35 (7.8%) malaria

cases were detected in the surveyed population; 94.3% were by

Plasmodium falciparum and the rest were the mixed infection with

P. vivax. Of these, 77.1% of the cases were asymptomatic. Two-thirds

(66.7%) of asymptomatic patients belonged to school-age group (6-14

years) (Table I). Mean age of participants with

asymptomatic malaria was significantly lower than the symptomatic cases

and non-malarial participants (Fig. 1). Asymptomatic

malaria showed association with age, and no association was observed

with gender. Risk of asymptomatic malaria was high in participants with

age £14 years

(OR 4.09, 95% CI 1.69 to 9.89, P=0.001).

|

|

Fig.1. Box-and-whisker plot showing

age-distribution among symptomatic and asymptomatic malaria

cases.

|

Controlling malaria in tribal populations requires

more effort and is of immense importance to achieve the target of

malaria elimination in the country. The malaria transmission season in

Chhattisgarh starts from August with the peak in October-November, the

asymptomatic reservoir present in the population in July-August may act

as a very important contributing factor for increased transmission in

the coming months. This is the time when vector density increases,

leading to high transmission in the following months. As microscopy is

the method available at Primary Health Center level, we used it to find

out the asymptomatic cases in monsoon season i.e., July end.

Asymptomatic malaria cases were reported to be five

times the clinical cases of malaria in low transmission season in

central Malli, West Africa [4]. 6.8% of the population was an

asymptomatic carrier of infection in eastern India [5]. Chaurasia, et

al. [6] reported that 77.7% of malaria infections were asymptomatic.

In our study, we found that 6% of the population was carrying

asymptomatic malarial infection in low transmission season.

Alves, et al. [7] previously reported an

association of asymptomatic malaria with older age group [7], whereas

previous Indian authors found a high prevalence of afebrile parasitemia

in younger individuals (<14 years) [8,9]. Aju-Ameh, et al. [10]

also showed a prevalence of asymptomatic malaria in the age group 2-10

years. Prevalence of asymptomatic malaria was reported to be higher in

age group >15 years in Chhattisgarh [6]. Our study contradicts findings

of Alves, et al. [7] and Chaurasia, et al. [6] and

supports the earlier reported observations [8-10].

The results of this study indicate that for malaria

control and elimination within the set time frame, strategies should be

designed to find out and target the reservoir of asymptomatic malaria

before the rainy season. This may show a significant reduction in number

of malaria cases in high transmission season. This strategy may be

highly effective for bringing areas in control phase of malaria to

pre-elimination phase. The limitation of this study is the small sample

size. Studies with a large sample size and at multiple sites are

warranted to better understand the problem of asymptomatic reservoir in

Chhattisgarh, and other areas with high transmission of malaria.

Contributors: DG, GS: conceptualized and

designed the study; DG: collected the data; RR: analyzed the data and

drafted the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of

manuscript, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of study.

Funding: None; Competing interest: None

stated.

References

1. National Framework for Malaria Elemination in

India (2016-2030). (Feb 3, 2016). National Vector Borne Disease Control

Program, Government of India. Available from:http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/246096.

Accessed November 5, 2018.

2. Das MK, Prajapati BK, Tiendrebeogo RW, Ranjan K,

Adu B, Srivastava A, et al. Malaria epidemiology in an area of

stable transmission in tribal population of Jharkhand, India. Malar J.

2017;16:181.

3. Walldorf JA, Cohee LM, Coalson JE, Bauleni A,

Nkanaunena K, Kapito-Tembo A, et al. School-age children are a

reservoir of malaria infection in Malawi. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0134061.

4. Coulibaly D, Travassos MA, Tolo Y, Laurens MB,

Kone AK, Traore K, et al. Spatio-temporal dynamics of

asymptomatic malaria: Bridging the gap between annual malaria

resurgences in a Sahelian environment. Am J Trop Med Hyg.

2017;97:1761-9.

5. Ganguly S, Saha P, Guha SK, Biswas A, Das S, Kundu

PK, et al. High prevalence of asymptomatic malaria in a tribal

population in eastern India. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:1439-44.

6. Chourasia MK, Raghavendra K, Bhatt RM, Swain DK,

Meshram HM, Meshram JK, et al. Additional burden of asymptomatic

and sub-patent malaria infections during low transmission season in

forested tribal villages in Chhattisgarh, India. Malar J. 2017;16:320.

7. Alves FP, Durlacher RR, Menezes MJ, Krieger H,

Silva LH, Camargo EP. High prevalence of asymptomatic Plasmodium vivax

and Plasmodium falciparum infections in native Amazonian populations. Am

J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;66:641-8.

8. Chaturvedi N, Krishna S, Bharti PK, Gaur D,

Chauhan VS, Singh N. Prevalence of afebrile parasitaemia due to

Plasmodium falciparum and P. vivax in district Balaghat (Madhya

Pradesh): Implication for malaria control. Indian J Med Res.

2017;146:260-6.

9. Chourasia MK, Raghavendra K, Bhatt RM, Swain DK,

Valecha N, Kleinschmidt I. Burden of asymptomatic malaria among a tribal

population in a forested village of central India: A hidden challenge

for malaria control in India. Public Health. 2017;147:92-7.

10. Aju-Ameh C. Prevalence of asymptomatic malaria in

selected communities in Benue state, North Central Nigeria: A silent

threat to the national elimination goal 2017. Edorium J Epidemiol.

2017;3:1-7.

|

|

|

|

|