|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2018;55:

909-910 |

|

Milky

Mesentery: Acute Abdomen with Chylous Ascites

|

|

Aakanksha Goel, Manish Kumar Gaur and Pankaj Kumar Garg

From Department of Surgery, University College of

Medical Sciences and Guru Teg Bahadur Hospital, Shahdara, Delhi, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Aakanksha Goel, House No 1 Sukh

Vihar, Delhi 110 051, India.

Email:

[email protected]

Received: July 21, 2017;

Initial Review: December 26, 2017;

Accepted: May 24, 2018.

|

Background: Clinical presentations of intestinal

lymphangiectasia include pitting edema, chylous ascites, pleural

effusion, diarrhea, malabsorption and intestinal obstruction. Case

Characteristics: An 8-year-old male child presented to the emergency

department with clinical features of peritonitis, raising suspicion of

appendicular or small bowel perforation. Intervention/Outcome:

Diagnosis of chylous ascites with primary intestinal lymphangiectasia

made on laparotomy. Message: Acute peritonitis may be a

presentation of primary intestinal lymphangiectasia and chylous ascites.

Keywords: Acute abdomen, Intestinal lymphangiectasia,

Peritonitis.

|

|

A

lthough lymphangiectasia is common in the neck

and axilla, it rarely involves intra-abdominal organs [1]. Intestinal

lymphangiectasia is characterized by dilatation of intestinal lymphatics

[2,3]. The clinical presentations of intestinal lymphangiectasia include

pitting edema, chylous ascites, pleural effusion, diarrhea,

malabsorption and intestinal obstruction. Acute peritonitis is a rare

presentation, and it may mimic other surgical pathologies [4,5].

Case Report

An 8-year-old male child presented to the emergency

department with periumbilical pain, vomiting and fever. There was no

history of tuberculosis or typhoid fever, and no history of trauma or

surgery. On examination, he was febrile with temperature of 39°C. The

abdomen was distended with diffuse tenderness and guarding. The total

leucocyte count was 22,500/mm 3.

Serum amylase was 23 units/L. Ultrasonography revealed a multiloculated

intra-abdominal collection. The presence of severe pain and fever

accompanied with clinical features of peritonitis, and sonological

evidence of abdominal collection raised the suspicion of appendicular or

small bowel perforation with sepsis. X-Ray of the chest and

abdomen were unremarkable, there was no evidence of free

intra-peritoneal air. In the absence of availability of emergency

computed tomography scan, the patient was taken up for emergency

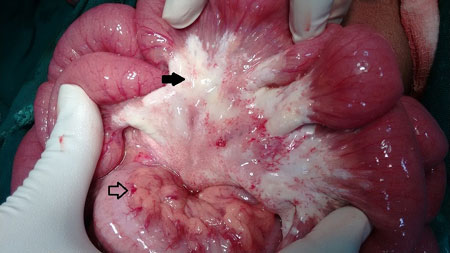

laparotomy for the acute abdomen. Laparotomy revealed 150 ml of milky

white ascitic fluid and chalky white plaques in the mesentery. A few

mesenteric lymph nodes were seen (Fig. 1). The small bowel

and the appendix appeared grossly normal. A clinical diagnosis of

chylous ascites with dilated mesenteric lymphatics (lymphangiectasia)

was made. The chylous fluid was drained and a thorough peritoneal lavage

was done. Biopsies were taken from the mesenteric lymph nodes and

peritoneum.

|

|

Fig. 1 Chalky white plaques in

mesentery due to dilated lymphatics (bold arrow). Normal fatty

yellow mesentery (lined arrow).

|

Histopathological report was negative for

tuberculosis and malignancy. The ascitic fluid was rich in triglycerides

(254 mg/dL) and demonstrated chylomicrons and lymphocytes on biochemical

analysis. Culture and gram stain were negative. Serum LDL, HDL and

triglyceride values were normal. The postoperative period was

uneventful. The abdominal drain was removed on post-operative day 2 with

no significant output. He was discharged on a high protein and low fat

diet, and was asymptomatic at 1-year post-surgery follow up.

Discussion

Intestinal lymphangiectasia is classified as primary

or secondary, based on the underlying etiology. Primary intestinal

lymphangiectasia represents a congenital disorder of mesenteric

lymphatics, whereas secondary is associated with diseases like

constrictive pericarditis, lymphoma, pancreatitis, trauma, intestinal

malignancy, or may be acquired after surgery [6]. Intestinal

lymphangiectasia is often associated with chylous ascites which may

easily be mistaken as purulent fluid. The most common cause of chylous

ascites in the pediatric population is congenital lymphatic

malformation, others being malignancy, tuberculosis, trauma, cirrhosis

and post-surgery [7]. The principal mechanisms for formation of chylous

ascites are related to disruption of the lymphatic system, from any

cause.

Dietary long-chain triglycerides are converted into

monoglycerides and free fatty acids and absorbed as chylomicrons in the

small bowel lymphatic system, which is responsible for high triglyceride

content and the milky appearance of lymph. Medium chain triglycerides,

constituting approximately one-third of dietary fat, on the other hand,

are absorbed directly by the portal venous system, which is the

rationale for their use in the conservative management of chylous

ascites [7].

Loss of chyle into peritoneal cavity can lead to

serious consequences because of the loss of essential proteins, lipids,

immunoglobulins, vitamins, electrolytes, and water. In most cases,

patients respond to low fat and high protein diet, enriched with

medium-chain fatty acids and no surgery is required. It is very

important to replenish fluid and electrolyte losses and treat vitamin

deficiencies [4]. Emergency exploratory laparotomy is mostly done only

in cases with acute chylous peritonitis for a preoperative suspicion of

bowel perforation; however, it gives the opportunity to evacuate the

peritoneal fluid, wash the abdominal cavity, and in certain cases, treat

the cause.

In case of chronic or debilitating ascites associated

with poor weight gain, hypoproteinemia and abdominal distension,

elective surgical treatment to treat the lymphatic fistula is

indispensible. Preoperative lymphangiography or lymphoscintigraphy is

helpful in identifying the anatomical location of the leakage or the

presence of a fistula in such presentations [8]. In our case, the

diagnosis of primary intestinal lymphangiectasia was established by the

presence of chylous ascites (rich in triglycerides and chylomicrons),

and the classical appearance of white chalky mesentery in the absence of

any secondary cause.

Contributors: All authors have designed,

contributed and approved the manuscript.

Funding: None, Competing interest: None

stated.

References

1. Pandey D, Garg PK, Jana M, Sharma J.

Retroperitoneal lymphangiectasia. ANZ J Surg. 2016;86:517-8.

2. Isa HM, Al-Arayedh GG, Mohamed AM. Intestinal

lymphangiectasia in children. Saudi Med J. 2016;37:199-204.

3. Rashmi MV, Murthy BN, Rani H, Kodandaswamy CR,

Arava S. Intestinal lymphangiectasia - a report of two cases. Indian J

Surg. 2010;72:149-51.

4. Fang F, Hsu S, Chen C, Chen T. Spontaneous chylous

peritonitis mimicking acute appendicitis/ : A case report and review of

literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:154-6.

5. Vettoretto N, Odeh M, Romessis M, Pettinato G,

Taglietti L, Giovanetti M. Acute abdomen from chylous peritonitis: Case

report and literature review. Eur Surg Res. 2008;41:54-7.

6. Suresh N, Ganesh R, Sankar J, Sathiyasekaran M.

Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia. Indian Pediatr. 2009;46:903-6.

7. Al-busafi SA, Ghali P, Deschênes M, Wong P.

Chylous ascites: Evaluation and management. ISRN Hepatol.

2014;2014:240473.

8. Campisi C, Bellini C, Eretta C, Zilli A, Rin E da,

Davini D, et al. Diagnosis and management of primary chylous

ascites. J Vasc Surg. 2006;43:1244-8.

|

|

|

|

|