|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2018;55:885-892 |

|

Management of Childhood

Functional Constipation: Consensus Practice Guidelines of Indian

Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition

and Pediatric Gastroenterology Chapter of Indian Academy of

Pediatrics

|

|

Surender Kumar Yachha

1,

Anshu Srivastava1,

Neelam Mohan2,

Lalit Bharadia3

and Moinak Sen Sarma1;

for

the Indian Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology,

Hepatology and Nutrition Committee on Childhood Functional Constipation,

and Pediatric Gastroenterology Subspecialty Chapter of Indian Academy of

Pediatrics

From 1Department

of Pediatric Gastroenterology, SGPGIMS, Lucknow; 2Department

of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Liver Transplantation,

Medanta Hospital, Gurgaon; and 3Fortis Escorts

Hospital, Jaipur; India.

List of other collaborators in Appendix 1.

Correspondence to: Dr Surender Kumar Yachha,

Professor and Head, Department of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Sanjay

Gandhi Postgraduate Institute of Medical Sciences, Lucknow 226 014,

India.

Email: [email protected]

Published online: June 13, 2018.

PII:S097475591600121

|

|

Justification: Management

practices of functional constipation are far from satisfactory in

developing countries like India; available guidelines do not

comprehensively address the problems pertinent to our country.

Process: A questionnaire-based

survey was conducted among selected practising pediatricians and

pediatric gastroenterologists in India, and the respondents agreed on

the need for an Indian guideline on the topic. A group of experts were

invited to present the published literature under 12 different headings,

and a consensus was developed to formulate the practice guidelines,

keeping in view the needs in Indian children.

Objective: To formulate practice

guidelines for the management of childhood functional constipation that

are relevant to Indian children.

Recommendations: Functional

constipation should be diagnosed only in the absence of red flags on

history and examination. Those with impaction and/or retentive

incontinence should be disimpacted with polyethylene glycol (hospital or

home-based). Osmotic laxatives (polyethylene glycol more than 1 year of

age and lactulose/lactitol less than 1 year of age) are the first line

of maintenance therapy. Stimulant laxatives should be reserved only for

rescue therapy. Combination therapies of two osmotics, two stimulants or

two classes of laxatives are not recommended. Laxatives as maintenance

therapy should be given for a prolonged period and should be tapered off

gradually, only after a successful outcome. Essential components of

therapy for a successful outcome include counselling, dietary changes,

toilet-training and regular follow-up.

Keywords: Lactulose, Laxatives, Polyethylene

glycol, Rescue therapy.

|

|

F

unctional constipation is a common problem in

children. Although some guidelines exist for management of childhood

constipation, there are no such guidelines for Indian children. In order

to understand the existing practices and magnitude of the problem, a

questionnaire was prepared with 22 questions and circulated to

practicing pediatricians and pediatric gastroenterologists in India from

October to December, 2014 using Monkey Survey tool. All the respondents

felt the need for an Indian guideline. To accomplish this goal, a group

of pediatric gastroenterologists and surgeons searched the published

literature under 12 headings. A two-day deliberation was held on 19-20

September, 2015 at Jaipur, attended by selected pediatricians, pediatric

gastroenterologists and pediatric surgeons (Annexure 1).

Each expert presented the existing literature, which was discussed

inclusive of experiences and a consensus opinion was reached on

different issues.

Functional constipation constituted 30% of pediatric

gastroenterology office practice, 4-5% of all referrals to pediatric

gastroenterology tertiary care centers and 0.8-1% of all pediatric cases

in medical colleges. At the end of the meeting, it was decided to

include these recommendations as a guideline on the evaluation and

management of functional constipation in children in India. A writing

group was designated for the same. The draft was sent by email to all

experts and their suggestions were incorporated in the final guidelines.

Definitions

Normal stool frequency: There are very few

studies on normal stool frequency and consistency in Indian children.

The average stool frequency of Indian children is as follows: <1 month

age: 3-4 times/day; 1 month to 1 year age: 1.5-2 times/day; 1 to 2 year

age: 1-2 times/day, mostly formed; older than 2 year age: 1 time/day

[1,2].

Constipation: A delay or difficulty in defecation

sufficient to cause significant distress to the patient is defined as

constipation. When the duration of constipation is less than 4 week, it

is labeled as acute constipation and when the duration is more, it is

labeled as chronic constipation.

Based on the North American Society of Pediatric

Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) guidelines, Rome

III criteria [3,4] and expert opinion, the definition recommended for

application in Indian children is given in Box 1.

|

Box 1 Definition of Constipation for Use

in Indian Children

• Duration of more than 4 weeks for all ages;

and

• Presence of

³2

of the following: (a) defecation frequency

£2

times per week, (b) fecal incontinence

³1

times per week after the acquisition of toileting skills, (c)

history of excessive stool retention, (d) history of

painful or hard bowel movements, (e) presence of a large

mass in the rectum or on per abdomen examination, (f)

history of large-diameter stools that may obstruct the toilet

(This may not be elicitable for majority of Indian children who

do not use the Western type of toilet).

|

Based on normal stool frequency of >1/day in Indian

children of older than 2 year, physicians should be guided more by the

stool consistency and other features of functional constipation rather

than stool frequency. Stool frequency of

£2/week as defined in

Western guidelines may not be necessarily applicable in Indian children

and may miss a substantial number of children with constipation if this

criterion is taken in isolation. Collateral manifestations in the form

of irritability, decreased appetite and/or early satiety may be

observed, which improve after defecation.

The terms soiling/encopresis should not be used.

Instead, the term ‘fecal incontinence’ should be used. This is defined

as passage of stools in the undergarment. Fecal incontinence is

classified as: (a) Constipation-associated fecal incontinence and

(b) non-retentive fecal incontinence: diagnosed only if there is

no constipation and normal anal sphincter tone, and symptoms last for

more than 2 months in a child with a developmental age of

³4 years.

Refractory constipation: Constipation not

responding to optimal conventional treatment for at least 3 months,

despite good compliance [5]. These patients should be referred to a

pediatric gastroenterologist for evaluation.

History and Examination

History and examination are relevant in making a

diagnosis of constipation, differentiating functional and organic

constipation, looking for precipitants of functional constipation and

eliciting issues relevant to management like incontinence, impaction,

past treatment, treatment compliance and response to treatment. Clinical

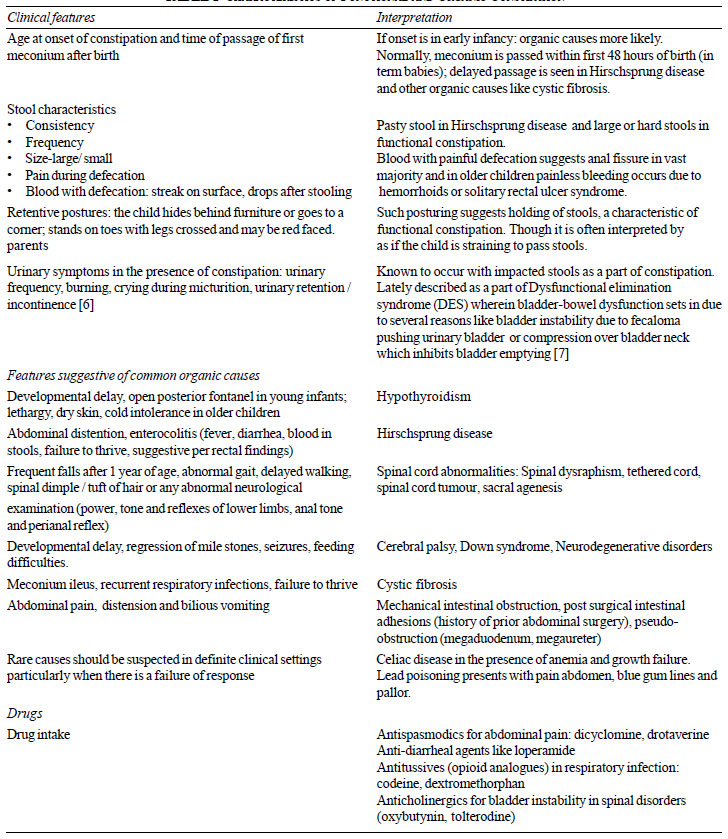

features and their interpretation are shown in Table I.

|

TABLE I Characteristics of Functional

and Organic Constipation

|

|

Dietary history: Details of diet should be taken:

intake of fruits and vegetables and refined foods (e.g., bakery

products), beverages etc. in older children, nature of feeds (breast

vs top feeds) and details of supplementary feeds in younger babies.

Exclusive and prolonged milk intake with minimal solids in young infants

is a major factor causing functional constipation in India (unanimous

opinion). These children are at an increased risk of iron deficiency

anemia.

Important precipitating factors of functional

constipation: The following are the most common factors which

initiate constipation in children

[8]: (a) premature initiation of toilet training

(normally toilet training should start not before 24 months in a

developmentally normal child) (b) drugs (Table I)

and inter-current illnesses, (c) quick and abrupt transition of

diet e.g. liquid to solid, breastfeeding to bottle feeding and (d)

change in local environment (start of schooling) and psychosocial

factors.

Evaluation

Patients should be examined thoroughly with proper

growth assessment to rule out an organic etiology (Table I).

Lower abdomen should be palpated for fecoliths (soft or hard indentable

masses). In the absence of abdominal fecoliths, anal fissure or anal

malformations, digital rectal examination (index finger in an older

child or little finger in an infant) helps in the following: (a)

presence of fecal impaction (seen in 50-70% children with functional

constipation and is diagnosed in the presence of a hard mass (fecal

mass) in the lower abdomen or presence of large, hard stools (fecolith)

on Digital rectal examination (DRE), (b) diagnosis of

Hirschprung’s disease (empty rectum, gush of stools/air on withdrawal of

finger), and (c) sacral mass lesion (palpable mass). DRE is not

essential in all cases or at all visits. It is recommended in the

following instances: (a) red flag symptoms or signs, (b)

onset <6 months of age, (c) non-responders despite good

compliance to therapy, and (d) patients presenting with fecal

incontinence to differentiate between constipation related and

non-retentive incontinence [9-11].

Red flags suggestive of organic constipation:

delayed passage of meconium, onset in early infancy, ribbon or

pellet stools, bilious vomiting, uniform abdominal distension, failure

to thrive, recurrent lower respiratory infections, cold intolerance,

neuro-developmental delay or regression, gush of stools on DRE, anal

malformations, abnormal neurological examination (paraspinal, lower

limbs and anorectal reflexes). Details are given in Table I.

Investigations: 95% children with

constipation have functional constipation and do not need any

investigations. Children with red flags (as above) suggestive of organic

etiology or those who are diagnosed as functional constipation but fail

to respond to therapy need diagnostic evaluation. A plain erect Xray

abdomen or barium enema is not required as a routine investigation in

all cases. [12-14].

Management of Functional Constipation

The following points should be addressed: patient

counseling, toilet training, modifications in diet, drug management, and

follow-up.

Patient Counseling

Salient pathophysiological aspects inclusive of

objective of treatment should be explained to the parents. Parents

should be clearly explained the cause of functional constipation,

preferably with a diagram. Any precipitating factors identified should

be eliminated or modified by appropriate advice (e.g. in a child

with exclusive milk feeding, (semi) solid diet supplementation should be

instituted; drugs causing constipation should be stopped; any

psychosocial factor operating needs to be addressed).

Toilet-training

Toilet training should not be started before 24

months of age; however, there is a variation in recommended age of

training between 3-4 years. Follow the ‘Rule of 1’: Toilet

training to be done by one person, one routine (5 min after each major

meal), one place, one word e.g. pooh/potty etc. In a child with

constipation: (a) make the child sit in the toilet, 2-3 times a

day for 5-10 minutes after meals (within 30 minutes of meal intake), (b)

make the defecation painless by treating anal fissures, if present, (c)

sit in squatting position in the Indian toilet or with foot rest in

English toilet/potty seat to have appropriate angulation of knees and

thighs to facilitate expulsion of stools, (d) reward system

(positive reinforcement) helps in motivating the child and avoiding

child-parent conflict.

Diet, Fiber and Water Intake

There are no well-conducted randomized controlled

studies of diet and treatment of constipation. Daily fiber requirement

is 0.5 gm/kg/day. Adequate intake of fiber-rich diet (cereals, whole

pulses with bran, vegetables, salad and fruits) is recommended at the

initial counseling. High fiber diet chart should be given to parents (as

per local practice). Restrict milk and encourage intake of semi-solids

and solids in younger children. Ensure adequate intake of water. Normal

activity is recommended.

Medical Therapy

It consists of initial phase of disimpaction in

patients with fecal impaction and a maintenance phase with laxatives.

Disimpaction

Rationale of disimpaction: Completely clear the

colon so that no residual hard fecal matter is retained. Thereafter the

maintenance laxative therapy can keep the bowel moving and empty so that

there is no retention. This enables rectum to achieve the normal

diameter and tone for proper anorectal reflexes and pelvic floor

coordination to facilitate normal stool expulsion

Options for Disimpaction: There are two ways of

disimpaction (Table II) (a) one-time hospital based

(100% success) (b) home based in split doses (68-97% success)

[14,15,17]. Rarely rectal enemas can be used as supplementary therapy to

clear the heavily hard loaded colorectal region. Oral route is preferred

as it non-invasive, has better patient acceptability, cleans the entire

colon and is equally effective as rectal disimpaction. Manual evacuation

of rectum is rarely required in patients failing oral and rectal

disimpaction but it should be performed under anaesthesia. Children

undergoing disimpaction should be reviewed within one week of

disimpaction to assess for re-impaction. Maintenance therapy should be

started only after effective disimpaction.

|

Agent |

Dosage |

Side effect |

Comments |

|

Oral agents |

|

Polyethylene glycol*(at home) |

1.5-2 g/ kg/ d in two divided |

Loose stools, bloating/ |

– |

|

doses for 3-6 d** only |

flatulence, nausea, vomiting |

|

|

depending upon the clarity of |

|

|

|

rectal effluent |

|

|

|

Polyethylene glycol solution |

25 mL/ kg/ h oral or by |

Nausea, vomiting, abdominal |

Caution: during one-time |

|

for lavage (in hospital) |

nasogastric tube in young |

cramps, rarely electrolyte |

disimpaction, watch for |

|

children |

abnormality, pulmonary |

bloating, abdominal |

|

End point is clear rectal |

aspiration |

distension or fluid overload |

|

effluent |

|

|

|

Young children may require |

|

|

|

intravenous fluids to maintain |

|

|

|

hydration |

|

|

|

Rectal agents |

|

Enemas (once per day) [15] |

|

|

|

Saline

|

Neonate <1 kg: 5 mL; >1 kg: 10 mL

>1y: 6 mL/kg, once or twice/day |

|

Not usually practised except

in special situations |

|

Phosphate soda |

2-18 y: 2.5 mL/kg, max 133 |

Hyperphosphatemia |

|

|

(Proctoclysis enema 100 mL) |

mL/dose |

Hypocalcemia |

|

|

PEG is a metabolically inert, large molecular weight soluble

polymer with capacity to retain intraluminal water. PEG is

available with or without electrolytes and as PEG 3350 or

4000.With the available evidence, PEG 3350 or 4000 and PEG with

or without electrolytes are all equally effective in

disimpaction [16]; *For one-time disimpaction there are Indian

formulations where one pack (containing polyethylene glycol of

118gm) should be reconstituted in 2 litres of water; ** For

maintenance or home-based disimpaction the preparation may vary

from 6.5g/scoop to 17g /sachet, and needs to be confirmed before

prescription. |

Maintenance therapy

There are different classes of laxatives used for

constipation (osmotic and stimulants).

Osmotic laxatives: These are the mainstay

of maintenance therapy in children [5]. These laxatives

draw water into the stool thereby making the stools softer and easy to

pass. The two main osmotic laxatives are polyethylene glycol (PEG) and

lactulose/lactitol (Table III). Based on the literature,

and the experience of the group, the recommendations are: (i) PEG

is the first line of therapy and is more effective as compared to

lactulose/lactitol. However in children <1 year of age, the only drug

recommended is lactulose/lactitol. (ii) In case of non-response

or intolerance due to non-palatability to PEG, the second line of

treatment is lactulose/lactitol which is safe for all ages. (iii)

Two osmotic agents like PEG and lactulose/lactitol should not be given

simultaneously. Combinations therapy with two classes of laxatives is

not recommended for children [5].

TABLE III Osmotic Laxatives for Maintenance Therapy

|

Osmotic laxative |

Dose |

Side effects |

Comment |

|

Polyethylene Glycol [16] |

0.5-1g/kg /day >12 mo age |

Bloating, |

Safe for both short and long |

|

|

Abdominal pain/cramps |

term use |

|

|

Vomiting |

|

|

|

Loose stools |

|

|

Disaccharides [19] |

|

|

|

|

Lactulose: non absorbable |

1mo-12mo: 2.5 mL BD; |

Abdominal distension |

Lactulose undergoes |

|

synthetic disaccharide, |

1-5y: 2.5-10 mL BD; |

Discomfort |

fermentation in the colon to |

|

consists of 2 molecules of |

5-18y: 5-20 mL BD |

|

yield short chain fatty acids, |

|

galactose and fructose |

|

|

CO2 and H2 |

|

Lactitol (b-galactosido- |

250 to 400 mg/kg/d |

|

|

|

sorbitol): monohydrate is a |

(15 mL =10 g of lactitol |

|

Lactitol is more palatable with |

|

analogue of lactulose, |

monohydrate |

|

better acceptability |

|

consists of galactose and |

|

|

|

|

sorbitol |

|

|

|

Stimulant Laxatives: Stimulant laxatives

are used only as rescue therapy No randomized controlled trials

are available in children regarding their efficacy. Stimulants are

usually required as rescue therapy (an acute or sudden episode of

constipation while being on regular compliant maintenance therapy).

These stimulants are given for a short duration of 2-3 days to tide over

the acute episode of constipation, and then stopped (Table IV)

[18].

TABLE IV Stimulant Laxatives: Rescue therapy

|

Name |

dose |

Side effects |

Comments |

|

Acts by stimulating colonic |

Oral (effect in 6-8 h), |

Short term usage is free from |

Contraindicated in children |

|

motility, promoting secretion |

single bedtime dose |

side effects. Abdominal cramps, |

with proctitis or anal fissures. |

|

and inhibition of absorption |

3-10 y: 5 mg/d |

diarrhea, hypokalemia, proctitis |

|

|

of water and electrolytes |

>10 y: 5-10 mg/d |

(rare), on prolonged use. |

|

|

in colon |

Should not be used in children |

|

|

|

below 3 years of age |

|

|

|

Rectal (effect within 30-60 min) |

|

|

|

2-10 y: 5 mg/d |

|

|

|

>10 y: 5-10 mg/d |

|

|

|

Sodium Picosulphate |

|

|

|

|

Acts through its active meta- |

Given as single dose |

Abdominal pain, nausea, and |

Contraindicated in setting of |

|

bolite that is produced by the |

1 mo-4 y |

diarrhea ~ 50% |

proctitis and gaseous abdo- |

|

intestinal bacteria and increases |

2.5-10 mg/d |

|

minal distension (underlying |

|

the peristalsis of gut |

4 to 18 y |

|

intestinal obstruction or |

|

2.5-20 mg/d Available as liquid |

|

paralytic ileus) |

|

In view of the side effects of these agents, it is advocated

for short duration as rescue therapy. |

Behavioral therapy and biofeedback; These

are helpful when constipation is associated with behavioral

co-morbidity or pelvic floor dysfunction in older children and

adolescents. This requires referral to centers with expertise.

Follow-up: Regular follow-up is essential.

At each follow-up, record the stool history, associated symptoms,

compliance with diet, medications and toilet-training. It is important

to have a stool diary for proper follow-up. Parents should maintain a

stool diary for objective assessment of response to therapy related to

stool frequency and consistency. First follow-up is advised at 14 days

to assess compliance. Subsequently, 1-2 monthly follow-up till normal

bowel habit is attained or physician is satisfied with response as

defined below as ‘successful outcome’. Further, 3-monthly follow-up for

a minimum period of one year. While on follow-up, the maintenance dose

may be increased or decreased to achieve daily passage of stools,

keeping in view the features of successful outcome.

Successful outcome of treatment should

be defined as (a) stool normalcy while on laxatives for a period

of at least 4 weeks of initiation of therapy, and (b) achievement

of stool normalcy for a minimum period of 6 months before tapering.

Normalcy of stools should defined as daily, not-hard, nor loose watery

stools, with absence of pain, straining, bleeding, posturing or

incontinence.

In Western countries, 50% of children with functional

constipation recover and are taken off medication within 6-12 months

[19, 20]. About 25% continue to experience symptoms up to adult age

[21]. Data from India show that 95% respond over a mean (SD) follow-up

of 15.0 (16.7) months [14]. 18.4% patients have recurrence of symptoms

on follow up; 10.5% of them require rescue disimpaction after a median

duration of 5.5 (1.5-17) months of the first disimpaction [14].

When to stop laxatives: No clear

guidelines exist and only expert opinions are available. Based on

the natural history, child should have been symptom-free while on

maintenance therapy for at least 6 months before attempting to taper the

laxatives. It is then advisable to taper gradually over a period of 3

months. Laxatives should never be stopped abruptly. In the developmental

stage of toilet training, medication should only be stopped once toilet

training and establishment of a regular stooling pattern is achieved.

Dietary and toilet training advice should continue even after stoppage

of laxatives. Triggers and precipitating factors of functional

constipation should have been adequately addressed. Parents should have

the knowledge about the management and also risk of relapse of symptoms

on stoppage of medication.

Refractory constipation: Those patients

not responding to a sustained optimal medical management of functional

constipation should be investigated for hypothyroidism, celiac disease,

Hirschprung disease, Cow milk protein allergy in young children, lead

poisoning and spinal abnormalities. These children also need evaluation

for presence of slow colonic transit, pelvic dyssynergia and

pseudo-obstruction, in centers with expertise.

Conclusion

Functional constipation should be diagnosed in the

absence of red flags. Impacted (incontinent) and non-impacted subgroups

should be identified. Management protocol should be adapted as per the

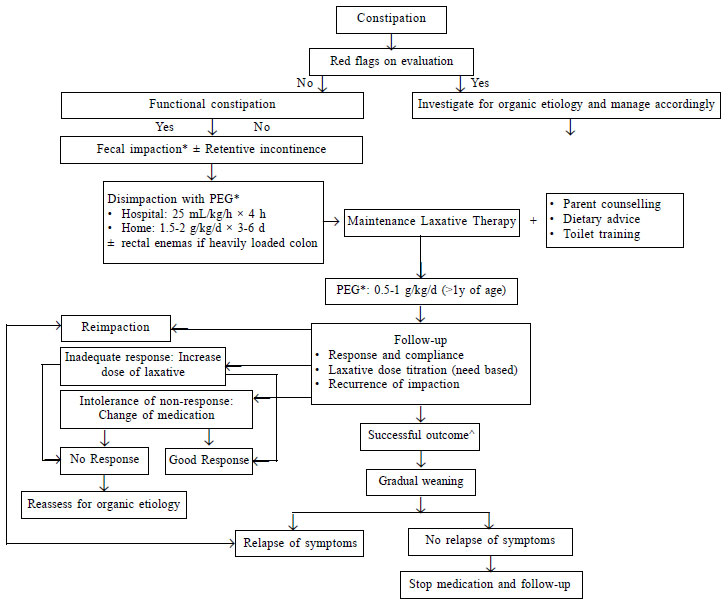

algorithm shown in Fig. 1. Emphasis should be laid on

toilet-training and importantly in counselling particularly related to

long-term usage of medical therapy.

|

|

*Fecal impaction (seen in 50-70% children

with functional constipation) is diagnosed in the presence of a

hard mass (fecal mass) in the lower abdomen or presence of

large, hard stools on DRE (fecolith); and ^Successful outcome

defined as (a) stool normalcy while on laxatives for a

period of at least after 4 weeks; initiation of therapy, and (b)

achievement of stool normalcy for a minimum period of 6 months

before tapering; PEG: polyethylene glycol (refer table 2);

stimulant laxatives are not a part of the routine management of

algorithm and should only be reserved for rescue therapy.

Fig. 1 Algorithm for the management

of childhood functional constipation.

|

Annexure 1: Participants of

the Indian Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and

Nutrition Committee on Childhood Functional Constipation, and Pediatric

Gastroenterology Subspecialty Chapter of Indian Academy of Pediatrics

Experts (in alphabetical order):

Lalit Bharadia, Jaipur (co-convenor); Vidyut

Bhatia, New Delhi; Vishnu Biradar, Pune; Vibhor Borkar, Mumbai; Barath

Jagadisan, Puducherry; Sakshi Karkra, Gurgaon; Praveen Kumar, New Delhi;

Neelam Mohan, Gurugram; Srinivas Sankarnarayanan, Chennai; Malathi

Sathiyasekaran, Chennai; Pramod Sharma, Jaipur; Anshu Srivastava,

Lucknow; Babu Ram Thapa, Chandigarh; Surender Kumar Yachha, Lucknow

(Convener).

Critical appraisal (in alphabetical order):

Raj Kumar Gupta, Jaipur; Natwar Parwal, Jaipur; Ashok Kumar Patwari,

New Delhi; VS Sankarnarayanan, Chennai

Writing committee:

Surender Kumar Yachha, Anshu Srivastava,

Moinak Sen Sarma

References

1. Yadav M, Singh PK, Mittal SK. Variation in bowel

habits of healthy Indian children aged up to two years. Indian J Pediatr. 2014;81:446-9.

2. Sujatha B, Velayutham DR, Deivamani N, Bavanandam

S. Normal bowel pattern in children and dietary and other precipitating

factors in functional constipation. J Clin Diag Res. 2015;9:SC12-5.

3. Hyman PE, Milla PJ, Benninga MA, Davidson GP,

Fleisher DF, Taminiau J. Childhood functional gastrointestinal

disorders: neonate/toddler. Gastro-enterology. 2006;130:1519-26.

4. Rasquin A, Di Lorenzo C, Forbes D, Guiraldes E,

Hyams JS, Staiano A, et al. Childhood functional gastrointestinal

disorders: child/adolescent. Gastroenterology. 2006;130: 1527-37.

5. Tabbers MM, DiLorenzo C, Berger MY, Faure C,

Langen-dam MW, Nurko S, et al. Evaluation and Treatment of

Functional Constipation in Infants and Children: Evidence-Based

Recommendations From ESPGHAN and NASPGHAN. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr.

2014;58:258-74.

6. Loening-Baucke V. Urinary incontinence and urinary

tract infection and their resolution with treatment of chronic

constipation of childhood. Pediatrics. 1997;100:228-32.

7. Burgers R, de Jong TP, Visser M, Di Lorenzo C,

Dijkgraaf MG, Benninga MA. Functional defecation disorders in children

with lower urinary tract symptoms. J Urol. 2013;189:1886-91.

8. Borowitz SM, Cox DJ, Tam A, Ritterband LM, Sutphen

JL, Penberthy JK. Precipitants of constipation during early childhood. J

Am Board Fam Pract. 2003;16:213-8.

9. Bardisa-Ezcurra L, Ullman R, Gordon J; Guideline

Development Group. Diagnosis and Management of Idiopathic Childhood

Constipation: Summary of NICE Guidance. BMJ. 2010;340:c2585.

10. Gold DM, Levine J, Weinstein TA, Kessler BH,

Pettei MJ. Frequency of digital rectal examination in children with

chronic constipation. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:377-9.

11. Rockney RM1, McQuade WH, Days AL. The plain

abdominal roentgenogram in the management of encopresis. Arch Pediatr

Adolesc Med. 1995;149:623-7.

12. Pashankar D. Childhood constipation: evaluation

and management. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2005;18:120-7.

13. Chogle A, Saps M. Yield and cost of performing

screening tests for constipation in children. Can J Gastroenterol. 2013;27:e35-8.

14. Khanna V, Poddar U, Yachha SK. Etiology and

clinical spectrum of constipation in Indian children. Indian Pediatr.

2010;47:1025-30.

15. Bekkali NLH, van den Berg MM, Dijkgraaf MG, van

Wijk MP, Bongers ME, Liem O, et al. Rectal fecal impaction

treatment in childhood constipation: enemas versus high doses oral PEG.

Pediatrics. 2009;124:e1108-15.

16. Chen SL, Cai SR, Deng L, Zhang XH, Luo TD, Peng

JJ, et al. Efficacy and complications of polyethylene glycols for

treatment of constipation in children: A meta-analysis. Medicine

(Baltimore). 2014;93:e65.

17. Guest JF, Candy DC, Clegg JP, Edwards D, Helter

MT, Dale AK, et al. Clinical and economic impact of using

macrogol 3350 plus electrolytes in an outpatient setting compared to

enemas and suppositories and manual evacuation to treat paediatric

faecal impaction based on actual clinical practice in England and Wales.

Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23:2213-25.

18. Gordon M, Naidoo K, Akobeng AK, Thomas AG.

Osmotic and stimulant laxatives for the management of childhood

constipation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012:11;7:CD009118.

19. Loening-Baucke V. Prevalence, symptoms and

outcome of constipation in infants and toddlers. J Pediatr.

2005;146:359-63.

20. Pijpers MA, Bongers ME, Benninga MA, Berger MY.

Functional constipation in children: A systematic review on prognosis

and predictive factors. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;50:256-68.

21. Bongers ME, van Wijk MP, Reitsma JB, Benninga

MA. Long-term prognosis for childhood constipation: clinical outcomes in

adulthood. Pediatrics. 2010;126: e156-62.

|

|

|

|

|