|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2018;55: 865-870 |

|

Postnatal Maturation of Amplitude Integrated

Electroencephalography (aEEG) in Preterm Small for Gestational

Age Neonates

|

|

Kamaldeep Arora,

Anu Thukral, M Jeeva Sankar, Sheffali Gulati, Ashok K

Deorari, Vinod K Paul and Ramesh Agarwal

From Newborn Health Knowledge Centre, WHO

Collaborating Centre For Training and Research in Neonatal Care,

Department of Pediatrics, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New

Delhi, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Ramesh Agarwal, Professor,

Division of Neonatology, Department of Pediatrics, All India Institute

of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India.

Email: [email protected]

Received:January 19, 2017;

Initial review: January 20, 2017;

Accepted: July 21, 2018.

|

|

The primary objective was to evaluate

the postnatal maturation pattern on aEEG during first two weeks of life

in clinically stable and neurologically normal preterm small for

gestational age (PSGA) and gestation matched (1 week) preterm

appropriate for gestational age (PAGA) neonates born between 300/7 and

346/7 weeks of gestation. Methods: Serial aEEG tracings were

recorded on 3rd, 7th and 14th day of life. The primary outcome was total

aEEG maturation score. Three blinded assessors assigned the scores.

Results: We analyzed a total of 117 aEEG recordings in 40 (19 PSGA

and 21 PAGA) neonates. The baseline characteristics were comparable

except for birthweight [1186 (263) vs 1666 (230) g]. There was no

difference in the mean (SD) total scores on day 3 (9.0 (1.8) vs.

9.5 (1.1), P=0.32) and day 14 of life, but was lower in PSGA

infants on day 7 (8.6 (2.4) vs. 10.1 (1.1), P=0.02). On

multivariate analysis, maturation of PSGA neonates was found to be

significantly delayed at any point of life from day 3 to day 14 (mean

difference, -0.8, 95 % CI: -1.6 to -0.02, P=0.04). Conclusion:

Lower aEEG maturation score on day 7 possibly indicates delayed

maturation in PSGA neonates in the first week of life.

Keywords: Electrophysiology, Neuronal

maturation, Outcome.

|

|

P

reterm neonates are at a risk of developmental

delay, visual and hearing problems, behavioral problems and learning

disabilities [1]. Nearly 20% of the preterm neonates are growth retarded

thus further increasing their jeopardy [2]. Preterm small for

gestational age (PSGA) neonates have decreased cortical volume, myelin

reduction, neuronal degeneration in the hippocampus and axonal

degeneration in periventricular region [2,3].

The brain electrographic pattern and activity

assessed by electroencephalogram (EEG) is an indicator of neuronal

activity and differentiation [4].

Amplitude integrated electroencephalogram (aEEG) is

used as a bedside device for continuously assessing the cerebral

electrical activity and its practical and prognostic use has been

demonstrated in many studies in term and preterm infants [5-11]. We

hypothesized that postnatal maturation of aEEG would be delayed in PSGA

as compared to their AGA counterparts. To date, only three studies from

developed countries have assessed the aEEG maturation specifically in

PSGA neonates [12-14]. The evidence is thus limited, with aspect to the

aEEG maturation pattern in stable preterm neonates which may be

important to decipher, given the alteration of aEEG patterns by

different morbidities and intracranial insults [15]. Hence, we designed

this study to evaluate the aEEG maturation pattern in preterm small for

gestational age neonates and compare their maturation with appropriate

for gestational age neonates, by using a validated aEEG maturation

scoring.

Methods

This prospective observational study was conducted in

the neonatal intensive unit of our institution from June 2010 to

December 2011. Written informed consent was obtained from one of the

parents, and the study was approved by the Institutional ethics

committee of All India Institute of Medical sciences, New Delhi, India.

Clinically stable preterm neonates (30 +0/7

to 34+6/7 weeks) were

included. Neonates with perinatal insult (Apgar score 2 or less at 5

minutes), major congenital anomalies, any grade of intraventricular

hemorrhage (IVH), periventricular leucomalacia (PVL), necrotizing

enterocolitis, evidence of central nervous system infection, clinical

seizures or suspected metabolic disorders

were excluded.

A log book was maintained to keep track of all the

neonates. Best gestational age (GA) was assigned based on the last

menstrual period, or the modified Expanded New Ballard score, if the

mother was not sure about the dates or if the discrepancy in assessment

and dates was more than two weeks [22]. SGA was defined as less than 10 th

centile for gestation according to the AIIMS intrauterine charts [23].

Cranial ultrasound (CUS) was performed on all

subjects by the radiologist, as per unit protocol at postnatal age 3, 7

and 14 day of life to rule out intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH),

periventricular leucomlacia (PVL) or any cranial malformation.

The aEEG tracings were recorded using the amplitude

integrated EEG machine (Nicolet, Viasys, San Diego CA, United States),

as per standard methodology [24]. Each recording was done for at least

4-hour duration to ensure good sleep-wake cycling recording [25].

Continuous impedance check was done throughout the recording. The

tracings with impedance >20 kOhm were discarded.

The primary outcome variable was total aEEG

maturation score as per Burdjalov, et al. [7]. Each tracing of

the subject was analyzed by three independent assessors. The methods

adopted for scoring the aEEG traces are summarized in Box I.

The secondary outcome variables were the scores of the four individual

parameters of maturation.

|

Box I Methods Adopted for Assigning The

aEEG Score

Step 1: Training of assessors

Three independent assessors* were trained for

analyzing the recorded aEEG’s. Each assessor was provided with

study material and video CD of aEEG. After the training

sessions, assessors were provided with sample aEEG records, of

various patients with varying gestational age and relevant

clinical scenarios.

Step 2: Analyzing the aEEG recordings

The assessors were blinded to gestation,

birth weight, and postnatal age at which aEEG was recorded. They

analyzed the aEEG tracings individually and assigned the scores

to each component of aEEG trace. They submitted their scores to

the principal investigator (KA).

Step 3: Assigning the final scores

The principal investigator assigned the final

scores based on the concordance between the three outcome

assessors – if the scores given by all three assessors were the

same, that score was recorded as the final score. However, if it

was different, the three assessors reviewed the aEEG tracing

together to reach a consensus score. This score was then

recorded as the final score. Concordance among assessors was

>95%.

*The outcome assessment team (three members)

included neonatology fellows/faculty level personnel with

experience and competency in neonatology.

|

According to the study done by Burdjalov, et al.

[7] the maturation score in neonates with 30-34 weeks of gestation on

day 3 of life was 10. A study on conventional EEG in term SGA neonates

versus the term AGA neonates followed till three months of age revealed

50% less amplitude in SGA cohort as compared to AGA cohort because there

was no study on mean total score (summation of all four components of

the aEEG tracing) evaluation in preterm infants prior to the initiation

of this study we assumed the difference in mean total score to be the

same as the score in amplitude alone in conventional EEG study. To

observe the difference in mean total score of at least 50% among the two

cohorts, with alpha error 5% and power of study 80 %, we needed to

enroll 20 neonates in each group.

Statistical analysis: The data were analyzed

using Stata version 11 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX). Normally

distributed, continuous data was analyzed by Student t test and

data which was non-normally distributed was analyzed by Wilcoxon rank

sum test. Chi-square or Fisher exact test were used to analyze

categorical data. Generalized estimating equation (GEE) analysis was

used to analyze the change in score from first aEEG recording to the

final one after adjusting for correlated values. P value of <0.05 was

considered as significant.

Results

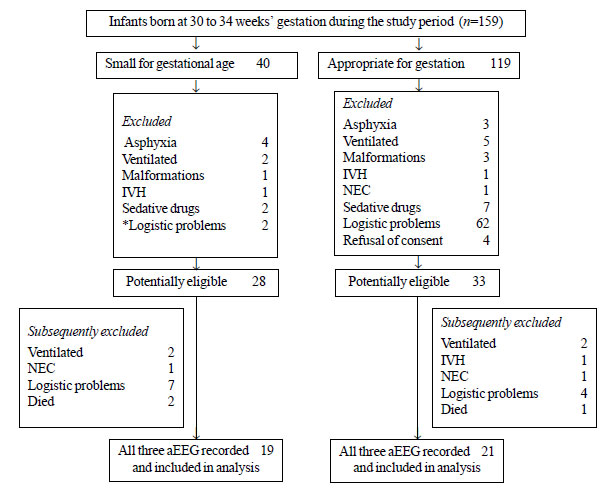

Of the total 159 neonates assessed for eligibility,

119 neonates were excluded (Fig. 1). The maternal

characteristics and baseline neonatal characteristics in PSGA (n=19)

and PAGA (n=21) cohorts were similar in the two groups (Table

I). No neonate in either group developed retinopathy of prematurity

(ROP) requiring treatment, or patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) needing any

intervention. There was no death in either cohort during the study

period.

|

|

Fig. 1 Flow of Patients in the study.

|

TABLE I Baseline Variables of the Study Population

|

Variable |

SGA (n=19) |

AGA (n=21) |

|

Maternal characteristics |

|

Age (y)*

|

27.8 (3.3) |

26.8 (3.9) |

|

Multigravida#

|

10 (52) |

16 (76) |

|

Booked#

|

16 (84) |

21 (100)

|

|

Gestational hypertension# |

4 (21) |

2 (9.5) |

|

Gestational diabetes |

3 (15.7) |

3 (14.2) |

|

PPROM# |

1 (5.2) |

2 (9.5)

|

|

Neonatal characteristics: At birth |

|

Gestation (wk)$ |

32 (30-34) |

33 (30-34) |

|

Weight (g)* |

1186 (263) |

1666 (230) |

|

Male# |

8 (32) |

15 (60) |

|

Mode of delivery# |

|

|

|

Vaginal delivery |

7 (37) |

12 (57) |

|

Twins# |

7 (36.8) |

9 (43) |

|

Apgar at 5 min$ |

8 (7-9) |

8 (6-9) |

|

Need for oxygen# |

2 (10.5) |

3 (14.2) |

|

BMV# |

2 (10.5) |

0 |

|

Postnatal |

|

Sepsis# |

6 (31) |

4 (19) |

|

NEC (I)# |

2 (10.5) |

0 |

|

Transient tachypnea of newborn# |

7 (36.8) |

9 (42.8) |

|

Respiratory distress syndrome |

2 (10.5) |

2 (9.5) |

|

CPAP# |

5 (26.3) |

3 (14.2) |

|

Total parenteral nutrition# |

6 (31.5) |

1 (4.7) |

|

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia# |

1 (5.2) |

0 |

|

VH (I)# |

1 (5.2) |

0 |

|

Data presented as *mean (SD), $median (range), #number

(%); PPROM: Preterm premature rupture of membranes; BMV: Bag and

mask ventilation. |

There was no difference in the total scores of the

two cohorts on day 3 of life and day 14 (Table II).

However, PSGA neonates had lower total score on day 7. On multivariate

analysis, maturation score of PSGA neonates was found to be

significantly delayed at any point of life from day 3 till day 14 of

life (mean difference, -0.8, 95 % CI: -1.6 to -0.017, P=0.045).

TABLE II Amplitude-integrated EEG Total Score Among Small for Gestational Age (SGA) and

Appropriate for Gestational Age (AGA) Neonates

|

Day of Life |

SGA (n=19) |

AGA (n=21) |

Mean difference (95 % CI)# |

|

3 |

9.0 (1.8 ) |

9.5(1.1) |

-0.5 (-1.5 to 0.5) |

|

7 |

8.6 (2.4) |

10.1(1.1) |

-1.4 (-2.6 to -0.3)$ |

|

14 |

10.2 (1.3 ) |

10.7 (0.8) |

-0.5 (-1.2 to 0) |

|

Values expressed as mean (SD); #Adjusted for

correlated values by generalized estimating equation (GEE);

$P=0.02. |

There was no difference in the Continuity scores of

the two cohorts at any time point of assessment (Table III).

The Cycling score and Lower border score were similar in the two groups

on day 3 and day 14. PSGA neonates had lower SWC score and ‘Lower border

score’ on day 7. The bandwidth score in PSGA neonates was lower than the

PAGA cohort on day 14 (3.3 (0.6 vs.3.7 (0.4, 95% CI 0 to 0.7).

TABLE III aEEG Score (Cycling, Continuity, Lower Border, and Bandwidth) Among Small for Gestational Age (SGA)

and Appropriate for Gestational Age (AGA) Neonates (N=40)

|

aEEG |

SGA* |

AGA* |

Mean difference |

P |

|

recording |

(n=19) |

(n=21) |

(95 % CI)# |

value |

|

aEEG continuity score |

|

Day 3 |

1.7 (0.4) |

1.9 (0.3) |

-0.1 (-0.36 to 0) |

0.31 |

|

Day 7 |

1.7 (0.5) |

2.0 |

-0.2 (-0.4 to 0) |

0.08 |

|

Day 14 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

-0.5 (-1.2 to 0) |

0.11 |

|

aEEG cycling score |

|

Day 3 |

2.2 (0.8) |

2.4 (0.7) |

-0.1 (-0.6 to -0.3) |

0.61 |

|

Day 7 |

2.1 (1.1) |

2.7 (0.7) |

-0.6 (-1.2 to 0) |

0.03 |

|

Day 14 |

2.8 (0.8) |

3.0 (0.6) |

-0.2 (-0.6 to 0) |

0.39 |

|

aEEG lower border score |

|

Day 3 |

1.8 (0.8) |

2.0 |

-0.1 (-0.2 to 0) |

0.13 |

|

Day 7 |

1.7 (0.4) |

2.0 |

-0.2 (-0.4 to 0) |

0.02 |

|

Day 14 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

- |

- |

|

aEEG bandwidth score

|

|

Day 3 |

3.1 (0.6) |

3.3 (0.4) |

-0.1 (-0.5 to 0) |

0.60 |

|

Day 7 |

3.0 (0.8) |

3.4 (0.5) |

-0.4 (-0.8 to 0) |

0.05 |

|

Day 14 |

3.3 (0.6) |

3.7 (0.4) |

-0.3 (-0.7 to 0) |

0.03 |

|

*Values expressed as mean (SD); #Adjusted for

correlated values by generalized estimating equation (GEE). |

Discussion

This study evaluates the maturation pattern of aEEG

in clinically stable PSGA neonates neonates during the first two weeks

of life. This study evaluated both prematurity and the SGA status on

maturation pattern using aEEG. PSGA neonates had similar total scores as

PAGA neonates on day 3 of life and day 14 and a lower total score on day

7. The maturation score of PSGA neonates in the present study was found

to be significantly delayed at any point of life from day 3 till day 14

of life.

The plausible explanation of the delayed maturation

score at any time point for PSGA neonates seems to be related to the

underlying reasons for growth retardation. The phenomenon for delay at

day 7 but not at day 3 or day 14 has not been understood very clearly.

The rationale behind this may be the delay in starting the enteral

feeds, which may show delay at day 7. Till date no studies have looked

at the long term outcome of this transient maturity. Malnutrition during

the critical phase of brain development may translate into delayed

myelination and subsequently to delayed maturation pattern [3]. A recent

study reported similar aEEG total scores in PAGA and PSGA neonates [12].

This study, however, did not specifically comment on the maturation

delay at any time point but revealed a higher number of bursts per hour

(objective quantitative parameter which indicates slower postnatal

adaptation of electrocortical function in PSGA neonates); thus

indirectly indicating a delay in electrocortical activity.

Nearly all PSGA neonates in the present study

achieved continuous pattern on aEEG at enrollment. These results are

similar to previous studies [12,14]. Continuity is one of the earliest

parameters to be achieved in aEEG recording [7,8]. It represents the

general status of the brain [26].

Our neonates were stable and had no clinical evidence of

neurological dysfunction, so the attainment of a continuous pattern on

aEEG is not unexpected at 30-34 weeks.

Our study suggested a comparable cycling pattern in

PSGA vs. PAGA neonates except on day 7 (second recording). The

study by Feler, et al. [13] suggested a comparable cycling

pattern in the two groups while the study by Schwindt, et al.

[14] suggested less cycling

activity in the SGA neonates. It may be difficult to compare our results

with the findings of the latter two studies as both these studies

evaluated the SWC pattern at a single time point in the first two weeks

which may not be representative of the changes which occur with

increasing postnatal age. SWC represents the integration of functions of

the higher centers of the brain and a premature sleep wake cycling in

PSGA neonates may represent a delay in synaptogenesis of the neurons

[22,26]. The study by Feler, et al. [13] also reported a higher

aEEG bandwidth in the PSGA neonates. The bandwidth decreases and the

lower border elevates with increasing maturity [7,13].

The strengths of our study include the evaluation of

clinically stable preterm neonates without any major morbidities

or requiring sedation [13,23,25]. In addition, low

impedance during the recording was ensured by adequate electrode

contact, continuous check on impedance and uninterrupted study periods

[26]. The duration of each tracing was atleast 4 hours. This helped

increase the chance of detecting even immature sleep-wake cycles.

In addition, the serial recordings on neonates

gave an insight in the maturation pattern at different time points,

rather than one study time point [22]. We used the controls from the

same population rather than other reference standards. The aEEG tracings

were assessed by three blinded assessors.

Our study had a few limitations, including a small

sample size. It is difficult to enroll stable PSGA neonates because this

subgroup of neonates suffers from high risk of perinatal asphyxia,

necrotizing enterocolitis and requirement of mechanical ventilation. The

second limitation was a short follow up aEEG recordings of these

neonates. In addition, ongoing recordings continuing upto term gestation

may have helped us to delineate the specific maturation pattern in these

neonates.

The maturation score of clinically stable and

neurologically normal P-SGA neonates PSGA neonates was found to be

significantly delayed at any point of life from day 3 till day 14 of

life. Further studies evaluating progressive aEEG maturation till term

age and the impact of the maturation pattern on subsequent

neuro-developmental outcomes may provide further insight into the

developmental pattern in these neonates.

Contributors: KA: primary responsibility for

protocol development, study implementation, data management and writing

the manuscript; AT, JS: development of the protocol and supervised

implementation of the study, analysed the tracings, assigned the scores

and contributed to writing of the manuscript. JS: helped in the

statistical analysis. VKP, AKD, SG: protocol development, gave critical

inputs in designing and execution of the study, data analysis and in

manuscript writing. RA: conceptualized and designed the study, analyzed

the aEEG tracings and assigned the scores, finalized the manuscript. He

will act as guarantor of paper. All authors have reviewed the final

manuscript and approved it.

Funding: None; Competing Interest:

None stated.

|

What This Study Adds?

•

Preterm SGA neonates show similar

total aEEG maturation score as Preterm AGA neonates on day 3 and

14, but a lower score on day 7 possibly indicating a delayed

maturation in these neonates in the first week of life.

|

References

1. Ward RM, Beachy JC. Neonatal complications

following preterm birth. BJOG. 2003;110S:8-16.

2. Vanderveen JA, Bassler D, Robertson CMT, Kirpalani

H. Early interventions involving parents to improve neurodevelopmental

outcomes of premature infants: a meta-analysis. J Perinatol.

2009;29:343-51.

3. Ozdemir OMA, Ergin H, Sahiner, T.

Electrophysiological assessment of the brain function in term SGA

infants. Brain Res. 2009;1270:33-8.

4. Morgane PJ, Austin K, Siok C, LaFrance R, Bronzino

JD. Power spectral analysis of hippocampal and cortical EEG activity

following severe prenatal protein malnutrition in the rat. Brain

Res.1985;354:211-8.

5. Toet MC, van der Meij W, de Vries LS, Uiterwaal

CS, van Huffelen KC. Comparison between simultaneously recorded

amplitude integrated electroencephalogram (cerebral function monitor)

and standard electro-encephalogram in neonates. Pediatrics.

2002;109:772-9.

6. Clancy RR, Dicker L, Cho S, Cook N, Nicolson SC,

Wernovsky G, et al. Agreement between long-term neonatal

background classification by conventional and amplitude-integrated EEG.

J Clin Neurophysiol.2011; 28:1-9.

7. Burdjalov VF, Baumgart S, Spitzer AR. Cerebral

function monitoring: A new scoring system for the evaluation of brain

maturation in neonates. Pediatrics. 2003;112:855-61.

8. Thornberg E, Thiringer K. Normal pattern of the

cerebral function monitor trace in term and preterm neonates. Acta

Paediatr Scand.1990;79:20-5.

9. Olischar M, Klebermass K, Kuhle S, Hulek M, Kohlhauser

C, Rücklinger E, et al. Reference values for amplitude-integrated

electroencephalographic activity in preterm neonates younger than 30

weeks’ gestational age. Pediatrics. 2004;113:e61-6.

10. Soubasi V, Mitsakis K, Nakas CT, Petridou S, Sarafidis

K, Griva M, et al. The influence of extrauterine life on the aEEG

maturation in normal preterm neonates. Early Hum Dev. 2009;85:761-5.

11. Toet MC, Hellström-Westas L, Groenendaal F, Eken

P, de Vries LS. Amplitude integrated EEG 3 and 6 hours after birth in

full term neonates with hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy. Arch Dis Child

Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1999;81:F19-23.

12. Griesmaier E, Burger C, Ralser E, Neubauer V, Kiechl-Kohlendorfer

U. Amplitude- integrated electroencephalo-graphy shows mild delays in

electrocortical activity in preterm neonates born small for gestational

age. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104:e283-8.

13. Yerushalmy-Feler A, Marom R, Peylan T, Korn A,

Haham A, Mandel D, et al. Electroencephalographic characteristics

in preterm infants born with intrauterine growth restriction. J Pediatr.

2014;164:756-61.

14. Schwindt E, Thaller C, Czaba-Hnizdo C, Giordano

V, Olischar M, Waldhoer T, et al. Being born small for

gestational age influences Amplitude-integrated electroencephalography

and later outcome in preterm infants. Neonatology. 2015;108:81-7.

15. Sommers R, Tucker R, Harini C, Laptook AR.

Neurological maturation of late preterm infants at 34 week assessed by

amplitude integrated electroencephalogram. Pediatr Res. 2013;74:705-11.

16. Ballard JL. Khoury JC, Wedig K, Wang L, Eilers-Walsman

BL, Lipp R. New Ballard Score: Expanded to include extremely premature

infants J Pediatr. 1991;119:417-23.

17. Singh M, Giri SK, Ramachandran K. Intrauterine

growth curves of live born single babies. Indian Pediatr. 1974;11:475-9.

18. Kidokoro H, Inder T, Okumura A, Watanabe K. What

does cyclicity on amplitude-integrated EEG mean? J Perinatol.

2012;32:565-9.

19. Lena Hellström-Westas. An Atlas of

Amplitude-Integrated EEGs in the Newborn, Second Edition: Informa

healthcare; 2008.

20. Kidokoro H, Kubota T, Hayashi N, Hayakawa M, Takemoto

K, Kato Y, et al. Absent cyclicity on aEEG within the first 24 h

is associated with brain damage in preterm infants. Neuropediatrics.

2010;41:241-5.

21. Hellström-Westas L, Rosén I, Svenningsen NW.

Predictive value of early continuous amplitude integrated EEG recordings

on outcome after severe birth asphyxia in full term infants. Arch Dis

Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1995;72:F34-8.

22. Van Leuven K, Groenendaal F, Toet MC, Schobben

AF, Bos SA, de Vries LS, et al. Midazolam and

amplitude-integrated EEG in asphyxiated full-term neonates. Acta

Paediatr. 2004;93:1221-7.

23. Shany E. The influence of phenobarbital overdose

on aEEG recording. Eur J Paediatr. Neurol. 2004;8:323-5.

24. Tas JD, Mathur AM. Using amplitude-integrated EEG

in neonatal intensive care. J Perinatol. 2010;30(Suppl): S73-81.

25. Ter Horst HJ, Brouwer OF, Bos AF. Burst

suppression on amplitude-integrated electroencephalogram may be induced

by midazolam: A report on three cases. Acta Paediatr. 2004;93:559-63.

26. Foreman SW, Thorngate L, Burr RL, Thomas KA.

Electrode challenges in amplitude-integrated electro-encephalography (aEEG):

Research application of a novel noninvasive measure of brain function in

preterm infants. Biol Res Nurs. 2011;13:251-9.

|

|

|

|

|