|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2016;53: 920-922 |

|

Central or Peripheral

Precocious Puberty: Diagnostic Difficulties

|

|

* María Eugenia López Valverde,

#Ana Villamañán

Montero, #Aránzazu

Garza Espí and

#Antonio de

Arriba Muñoz

From Departments of *Endocrinology and Nutrition, and

#Pediatric Endocrinology; Hospital Universitario Miguel

Servet, Spain.

Correspondence to: Dr María Eugenia López Valverde.

Endocrinology and Nutrition, Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet,

Spain. [email protected]

Received: August 24, 2015;

Initial review: October 20, 2015;

Accepted: May 27, 2016.

|

Background: An underlying identifiable organic

cause is present in up to 50% cases of central precocious puberty in

male patients. Case characteristics: A 7-years-8-months-old

presented with delayed puberal development. Analytical examinations

showed suppressed basal and stimulated levels of testosterone, LH and

FSH. Abdominal ultrasound and contrast cranial magnetic resonance

results were initially negative. Outcome: Germinoma was found on

cranial computer tomography. Conclusion: There is often a wide

time-lapse between symptoms and diagnosis of germinoma, so frequent

monitoring is vital.

Keywords: Central nervous system tumor, Germinoma,

Hypopituitarism.

|

|

Central precocious puberty is

of idiopathic origin in upto 95% of girls, while in up to 50% of males

there is an underlying identifiable organic cause [1]. It is therefore

important to take into account that diagnosis of idiopathic central

precocious puberty in boys must be a diagnosis of exclusion. One of

several organic causes is germinoma, an unusual tumour with variable

clinical manifestations. A specific characteristic of these tumours is

the considerable length of time that elapses between their onset and

their correct diagnosis on MRI scans.

Case-report

A male patient aged 7

years 8 months presented with a 3-month history of facial

acne and increase in testicular volume. Upon examination, he had a

testicular volume of 6 ml, penis stage IV, pubarche stage I; weight 25

kg (-0.46 SDS), height 124 cm, (-0.62 SDS), body mass index 16.26 kg/m2

and considerable facial acne, and a bone age of 9

years 3 months (predicted adult height 168.9 cm).

The remaining systemic examination showed normal results and the patient

did not have any neurological symptoms.

The results of the biochemical analyses showed

suppressed levels of LH and FSH (0.11 mUI/mL), androstenedione 0.09 ng/mL

(normal 0.3-3.1), DHEA-S 17 mcg/dL (normal 24±22), total testosterone

1.96 ng/mL (normal 1.75-7.81) and free testosterone 2.31 pg/mL (normal

0.04-0.09). In LHRH test, It was administered one single injection of

LHRH (100 µg intravenous), with basal blood extraction, and 20, 30 and

60 minutes afterwards: LH 0.11-0.71 mUI/mL and FSH 0.11-0.2 mUI/mL.

Serum b-HCG

levels were 5 mUI/mL (normal <1.2) and

afetoprotein 1.56 ng/mL

(normal 0-15).

|

| (a) |

(b) |

|

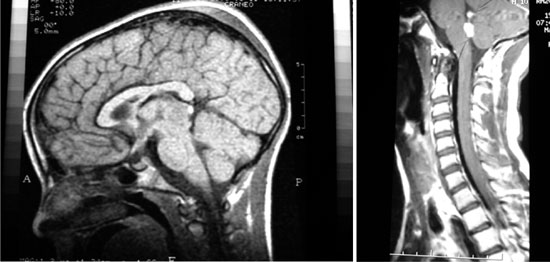

Fig. 1 Germinoma MRI imaging. (a)

MRI brain sagittal section showing germinoma in pineal region

(arrow). (b) Hyperintense mass lesions suggestive of germinoma

metastases (arrow) in fourth ventricle.

|

A gadolinium-enhanced cranial magnetic resonance

imaging (MRI) and abdominal ultrasound scan showed no abnormalities, but

following a testicular scan, a 1 cm nodule in the left testicle was

detected. Therefore, peripheral precocious puberty was suspected, and a

testicular biopsy was taken. However, given that the results of the

biopsy were normal, this then indicated a likely case of testotoxicosis.

Treatment with Keto-conazole was prescribed, and following three months

of treatment, his signs of puberty effectively stabilized (testicles 5-6

mL, improvement in facial acne), height 130.4 cm (0.28 SDS) and weight

(-0.3 SDS). However, due to a subsequent onset of polyuria and

polydipsia, a computerized tomography scan (CT) and contrast-enhanced

cranial MRI scan were taken, both of which presented normal results.

Additionally, a blood test was taken, which confirmed that he was

suffering from diabetes insipidus. The patient required desmopressin

treatment, which controlled the symptomatology. It was thought

b-HCG levels

were normal, so they were not monitored and repeat CT and MRI, were

again normal.

Around 21 months later, following continuous clinical

monitoring, the patient began with complaints of headaches and seizures.

Another contrast Gadolinium enhanced MRI scan detected a 2.2×2 cm pineal

tumour with triventricular hydrocephalus, diagnosed as an hCG secreting

tumour (high a-fetoprotein

and bhCG in

lumbar cerebrospinal fluid and on a ventricular level), which required

radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Following this treatment, the tumour was

no longer visible on the MRI scan, and tumour markers were negative. At

the age of 9 years 9 months,

the patient showed a regression in pubertal development (testicular

volume 3-4 mL, penis stage IV, no signs of pubarche), with a slow growth

rate of 0.3 cm/year, a height of 134.1cm (-1.38 SDS), weight 26.5 kg

(-1.07 SDS), and a bone age of 12 years. The clonidine stimulation test

confirmed a deficit of GH (maximum GH level: 0.38 ng/mL); however,

treatment was not given after a tumour recurrence was detected on the

MRI scan 18 months following diagnosis. The patient was administered

further radio- and chemo-therapy, but subsequently developed secondary

adrenal insufficiency which was treated with hydrocortisone. By the age

of 15 years 5 months, the

patient’s height was 145.3 cm (-3.65 SDS), weight 40.6 kg (-2.02 SDS),

testicular volume 10 mL, penis stage IV and pubarche stage IV, but he

had no facial or underarm hair. Basal LH and FSH levels were 1.8 and

13.4 mUI/mL respectively, and total testosterone levels were reduced

(0.07 ng/mL); GnRH stimulation test could not be done because health

state of the patient was seriously affected. So, treatment with

intramuscular testosterone was initiated for presence of secondary

hypogonadism.

The patient currently continues treatment of chronic

replacement therapy with hydrocortisone and testosterone.

Discussion

The diagnostic approach in precocious puberty can be

particularly complex. All of the information available initially

indicated peripheral precocious puberty, due to the absence of

gonadotropins, the negative results of the brain scan and initial

normality of the rest of the pituitary axis. However, there were certain

symptoms that implied central precocious puberty. Up to 60% of

germinomas do not show high âHCG levels, and where present, they tend to

be low, with averages values of 7.7 mUI/mL in some studies [2].

Additionally, diabetes insipidus is a symptom that frequently occurs in

up to 100% of patients with germinomas. Despite this, in this case,

there was no evidence on the serial cranial CT or MRI scans suggesting

any type of tumoral pathology. Thus, the most plausible suspected

diagnosis was peripheral precocious puberty, and the only viable option

was close patient monitoring.

CT and MRI scans are sensitive enough to diagnose

suprasellar or pituitary tumours. Neuroimaging was normal initially and

it was 2 years after the symptoms began that the pineal germinoma became

evident on the MRI brain scan. This is particularly relevant, because

there are few cases reported of germinoma in which symptoms actually

precede radiographic evidence [3]. Therefore, in the event that any

question should arise in diagnosis, it would seem advisable to monitor

b-HCG

levels rather than depending exclusively on the use of neuroimaging.

Although late diagnosis does not appear to affect survival rates in the

short-term [4], it does still have an impact on patient morbidity

because it increases the risk of disseminated disease and therefore

requires a more aggressive therapeutic treatment.

Given that germinoma is a radiosensitive tumour,

chemotherapy followed by irradiation enables a smaller dose of RT to be

given [5-7], which helps to achieve good long-term survival rates and

results in a decrease in side effects. We used a combination of both

treatments.

Due to the location of the tumour, the patient

developed hydrocephalus with secondary intracranial hypertension. When

this occurs, surgery is advised, but there is insufficient evidence to

determine whether a ventriculoperitoneal shunt or an endoscopic

ventriculo-stomy [8] is more suitable.

GH-deficiency is the earliest and most frequent

complication in patients who have been treated with cranial

radiotherapy. In this case, it was not treated due to the complexity of

the tumour and its subsequent recurrence. Additionally, both

radiotherapy and chemotherapy can cause hypogonadotropic hypogona-dism

in a considerable percentage of patients [9].

Diagnosis of germinomas is a complex issue.

Unfortunately, there is a small percentage of cases in which central

nervous system imaging do not reveal any pathological evidence.

Consequently, it is advisable to perform an exhaustive and frequent

follow-up of the patient, not only analytical or clinically, but also

with consecutive radiological brain imaging; this approach will prevent

from diagnostic delays and will minimize morbidity and mortality.

Contributors: All the authors have participated

in all the aspects of preparation of the manuscript.

Funding: None; Competing interest: None

stated.

References

1. Faizah MZ, Zuhanis AH, Rahmah R, Raja AA, Wu LL,

Dayang AA, et al. Precocious puberty in children: A review of

imaging findings. Biomed Imaging Interv J. 2012;8:e6.

2. Allen J, Chacko J, Donahue B, Dhall G, Kretschmar

C, Jakacki R, et al. Diagnostic sensitivity of serum and lumbar

CSF bHCG in newly Diagnosed CNS Germinoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer.

2012;59:1180-2.

3. Pomarède R, Finidori J, Czernichow P, Pfister A,

Hirsch JF, Rappaport R. Germinoma in a boy with precocious puberty:

evidence of hCG secretion by the tumoral cells. Childs Brain.

1984;11:298-303.

4. Sethi RV, Marino R, Niemierko A, Tarbell NJ, Yock

TI, MacDonald SM. Delayed diagnosis in children with intracranial germ

cell tumors. J Pediatr. 2013;163:1448-53.

5. O’Neil S, Ji L, Buranahirun C, Azoff J, Dhall G,

Khatua S, et al. Neurocognitive outcomes in pediatric and

adolescent patients with central nervous system germinoma treated With a

strategy of chemotherapy followed by reduced-dose and volume

irradiation. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;57:669-73.

6. Khatua S, Dhall G, O’Neil S, Jubran R, Villablanca

JG, Marachelian A, et al. Treatment of primary CNS germinomatous

germ cell tumors with chemotherapy prior to reduced dose whole

ventricular and local boost Irradiation. Pediatr Blood Cancer.

2010;55:42-6.

7. Echevarría ME, Fangusaro J, Goldman S. Pediatric

central nervous system germ cell tumors: A Review. Oncologist.

2008;13:690-9.

8. MacDonald SM, Trofimov A, Safai S, Adams J,

Fullerton B, Ebb D, et al. Proton radiotherapy for pediatric

central nervous system germ cell tumors: early clinical outcomes. Int J

Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011; 79:121-129.

9. Güemes Hidalgo M, Muñoz Calvo MT, Fuente Blanco L,

Villalba Castaño C, Martos Moreno GA, Argente J. Endocrinological

outcome in children and adolescents survivors of central nervous system

tumours after a 5 year follow-up. Ann Pediatr (Barc).

2014;80(6):357-364.

|

|

|

|

|