A

lveolar capillary dysplasia (ACD) is a rare

cause of irreversible persistent pulmonary hypertension. Fewer than

50 cases have been described since the first description by Janney,

et al. [1] in 1981 as a misalignment of pulmonary veins [2,3].

The etiology of disordered alveologenesis is not yet clearly

understood. Clinically, there are signs of respi-ratory failure not

responding to therapy. The definitive diagnosis can be established by

a lung biopsy [4].

Case Report

A full term 2700 g male infant was born by normal

vaginal delivery at the 38 week gestation after uncomplicated

pregnancy, with Apgar score 6/9/9. The physical examination detected

anorectal atresia and surgical treatment was planned. Preoperative

echocardiographic examination did not detect any structural

abnormality. Baby did not have tricuspid regurgitation sufficient to

generate a measurable signal. There was bidirectional (predominantly

left-to-right) shunting at the ductus arteriosus and foramen

ovale. The value of right ventricular pre-ejection period /

right-ventricular ejection time (PEP/RVET) measured by pulsed doppler

at the pulmonary valve was 0.4. The surgery was uneventful but a

short time bronchial hyperactivity appeared during induction of

anesthesia. After surgery, the infant required mechanical ventilation

with FiO2 0.21-0.3 for 18

hours. On the third postoperative day, the baby was intubated because

of dyspnea and impaired oxygenation despite the CPAP treatment. FiO

2

required was 1.0. One day later, there was a progression of severe

respiratory failure not responding to any therapy. The X-ray

examination of the chest did not reveal any pathological changes.

Despite resuscitation, mechanical ventilation, and cardiotonic

support, the infant died at the age of six days. Autopsy revealed a

patent foramen ovale and ductus arteriosus as a result of persistent

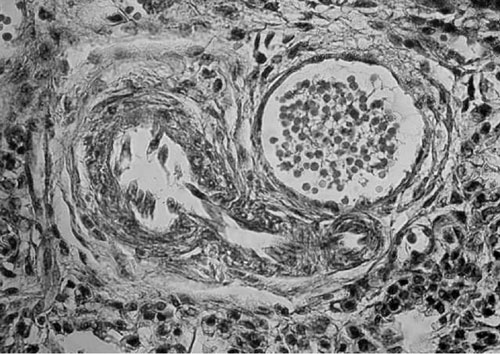

pulmonary hypertension (PPHN) Edwards stage I –II. Histological

examination diagnosed ACD with reduction of capillaries, apposition

of pulmonary veins and thickened alveolar-capillary septum (Fig.

1).

|

|

Fig. 1 Histological signs of

alveolar capillary dysplasia with hypertrophy of arterial media

and dysplastic vein pass along pulmonary artery sharing common

adventitia. |

Discussion

ACD is a rare lethal condition that has

been recognized in recent years as a cause of idiopathic PPHN. The

prevalence of ACD is not exactly known [1]. Occasional familiar

clustering and documented associations with other non-lethal

congenital anomalies, most frequently of genitourinary and

gastrointestinal tracts, have been reported [1,2,5]. Chang, et al.

and coauthors confirmed the deficiency of immunoreactivity of CD 117

hemangioblast precursor cells in lung tissue, which during

physiological circumstances produce chemo-reactive substances

responsible for vasculogenesis and formation of alveolo-capillary

membrane. There is a lack of expression of VEGF isoforms. Principal

pathomechanism of the disease is a failure of alveologenesis and

formation of blood-gas barrier. Histological analysis reveals

misalignment of pulmonary veins, dysplastic capillaries, hypertrophy

of pulmonary arteries, lymphangiectasis, and thickened alveolar –

capillary septum [7]. In physiological circumstances, pulmonary veins

are localized at the periphery of the lobule within interlobular

septa. In ACD, they pass along pulmonary arteries, sharing common

adventitia in the centre of lung lobule. It is likely that large

abnormal capillaries are immature vessels that are arrested at an

earlier step of vessels development and have not differentiated into

the smaller and more mature size [1, 8]. The dysplastic capillaries

may also fail to connect with the pulmonary arteries upstream, which

would explain why they are thick-walled in ACD [8].

The pathophysiology of ACD is unclear. It is

postulated that reduced number of pulmonary capillaries, hypoxic

vasoconstriction and altered vasoreactivity are causes of pulmonary

hypertension. The resulting increased right-sided pressure may lead

to right to left shunting across patent foramen ovale or ductus

arteriosus.

In 50% of cases, pulmonary hypertension progresses

within first 24 hours, in other 50% the symptoms develop within

several weeks called "the initial honeymoon period". The reason for

this period is unknown [9]. This relatively delayed presentation

could be ascribed to phenotypical variation of the disease, patchy

involvement of lungs or unexpected opening of shunts between

pulmonary arteries and veins [6]. Clinical presentation of ACD is

nonspecific. There are signs of respiratory failure with developing

hypoxemia. X-ray examination is frequently without

pathological changes. Sometimes bilateral nonspecific infiltrative

changes may be present. A variable stage of pulmonary hypertension

with right to left shunting and tricuspidal insufficiency can be

diagnosed by echocardiographic examination [10].

In our patient, the echocardiography was normal in

the preoperative period. Due to a rapid deterioration of clinical

condition of the baby there was no time left to repeat the

echocardiography.

ACD is a universally lethal disease. All the

aggressive therapies including inhaled nitric oxide, mechanical

ventilation and ECMO may only reduce transient hypoxemia but do not

lead to a long term survival. ACD should be suspected in newborns

with respiratory distress that is not responding to the therapy,

especially when other congenital anomalies are present. It is

recommended to consider early lung biopsy to reduce the number of

invasive, expensive and futile procedures that do not improve the

likelihood of survival [8].

Contributors: ZB collected the data and

drafted the paper. KM revised the manuscript for intellectual

content. AJ conducted the echocardiography and interpreted the

results. MZ acted as a guarantor of the study. The final manuscript

was approved by all authors.

Funding: Comenius University grant No.

37/2009 and VEGA grant.

Competing interests: None stated.

References

1. Janney CG, Askin FB, Kuhn G. Congenital

alveolar capillary dysplasia – an unusual cause of respiratory

distress in the newborn. Am J Clin Pathol.

1981;76:722-7.

2. Al-Hathol K, Philps S, Seshia M, Casiro O,

Alvaro RE, Rigatto H. Alveolar capillary dysplasia. Report of a case

of prolonged life without ECMO and review of the literature. Early

Hum Dev. 2000;57:84-5.

3. Thibeault DW, Garola RE, Kilbride HW. Alveolar

capillary dysplasia: An emergeting syndrome. J Pediatr.

1999;134:661-2.

4. Antao B, Samuel L, Kiely E, Spitz L, Malone M.

Congenital alveolar capillary dysplasia and associated

gastrointestinal anomalies. Fetal Pediatr Pathol.

2006;25:137-45.

5. Tibbalas J, Chow CW. Incidence of alveolar

capillary dysplasia in severe idiopatic persistent pulmonary

hypertension of the newborn. J Paediatr Child Health.

2002;38:397-400.

6. Chang KT, Rajadurai VS, Walford NQ, Hwang WS.

Alveolar capillary dysplasia: Absence of CD117 immunoreactivity of

putative hemangioblast precursor cells. Fetal Pediatr Pathol.

2008;27:27-140.

7. Ng PC, Lewindon PJ, Siu LK, To KF,Wong W.

Congenital misalignment of pulmonary veins : un usual syndrome

associated with PPHN. Acta Pediatr. 1995;84:349-53.

8. Galambos C, DeMello DE. Regulation of

alveologenesis : Clinical implications of impaired growth. Pathol.

2008;40:124-40.

9. Shioe A, Lee A, To K, Thumg KH, Lee TW, Yim A.

Alveolar capillary dysplasia with congenital misalignment of

pulmonary veins. Asian Cardiovas Thor Annalas. 2005;13:82-4.

10. Shankar V, Haque A, Johnson J, Pietsch J. Late presentation

of alveolar capillary dysplasia in an infant. Pediatr Crit Care.

2006;7:177-9.