|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2010;47: 851-856 |

|

Growth of Very Low Birth-Weight Indian Infants

During Hospital Stay |

|

Satish Saluja, Manoj Modi, Avneet Kaur, Anil Batra, Arun Soni, Pankaj Garg

and Neelam Kler

From the Department of Neonatology, Centre for Child

Health, Sir Ganga Ram Hospital, New Delhi, India.

Correspondence to: Satish Saluja, Department of

Neonatology, Sir Ganga Ram Hospital, New Delhi 110 060, India.

Email: [email protected]

Received: July 26, 2009;

Initial review: August 13, 2009;

Accepted: November 23, 2009.

Published online: 2010 March 15.

PII: S097475590900516-1

|

|

Abstract

Objectives: To evaluate the growth pattern of

Very Low Birth Weight (VLBW) infants (birthweight <1500g) during

hospital stay and to compare the growth of Small for gestational age (SGA)

and Appropriate for gestational age (AGA) infants.

Study design: Prospective observational

study.

Setting. Level III Neonatal Intensive Care

Unit (NICU) in Northern India.

Participants: A cohort of 97 VLBW infants,

admitted to NICU at Sir Ganga Ram Hospital, from 1 January, 2007 to 31

July, 2008.

Intervention/Measurement: Weight, length and head

circumference (HC) were serially measured from birth till discharge and

respective Z scores were calculated as per data from Fenton’s

references. Growth was also assessed by superimposing these trends on

Ehrenkranz’s postnatal growth charts.

Results: The mean Z scores for

weight, length and HC at birth were –1.17, –1.09 and –0.54,

respectively. These decreased to –2.16, –2.24 and –1.35, respectively by

discharge. Both SGA and AGA infants exhibited a decrease of

approximately 1 Z score in all parameters. On postnatal charts,

growth of infants remained at or above respective reference lines,

except in those below 1000g at birth. Average daily weight gain after

regaining birth weight was 15.18 ± 1.7 g/kg/d, whereas the increase in

HC and length were 0.48 ± 0.2 cm/week and 0.60 ± 0.4 cm/week,

respectively. These increments when compared to the intrauterine growth

rates, indicated discrepant growth trends.

Conclusions: VLBW infants suffered

significant growth lag during NICU stay and exhibited disproportionately

slow growth of HC and length.

Key words: VLBW infants, Growth, Z score, Weight, Length, Head

circumference, India.

|

|

P

ostnatal growth of Very Low Birth

Weight (VLBW) infants (birthweight <1500g) remains a subject of concern

for neonatologists. Infants born VLBW are at increased risk for impaired

growth, due to certain factors during intrauterine life, exposure to

hostile ex-utero environment and poorly understood nutritional needs.

Despite improvement in care of VLBW infants, they continue to suffer

growth lag during neonatal period and early infancy. Most of these infants

experience catch up growth much later, by 8-20 years(1). Poor postnatal

growth has been associated with subnormal long-term physical growth and

neurodevelopment outcomes (2-4). The postnatal growth pattern in VLBW

infants during hospital stay and beyond has not been reported from this

subcontinent.

We conducted this study to document and describe the

growth patterns of VLBW infants during NICU stay and to analyze the

difference, if any, between those born appropriate or small for

gestational age (AGA or SGA).

Methods

VLBW infants admitted to neonatal intensive care unit

at Sir Ganga Ram Hospital, New Delhi from 1st January 2007 to 31st July

2008 were followed prospectively from birth till discharge. Infants who

stayed in the hospital for less than 10 days or those admitted after 24

hours of birth or with major congenital malformations were excluded. This

study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and hospital Ethics

Committee. Parental consent was obtained at the time of enrolment.

Gestational age was recorded as per obstetrical estimates based on first

trimester ultrasonography or if not available, by date of last menstrual

period.

Weight was taken by an electronic weighing scale, which

was calibrated at regular intervals. It was recorded every day till birth

weight was regained and then every week till discharge. Length and head

circumference (HC) were recorded using standard techniques between 12 to

24 hrs initially and then every week till discharge. The minimum range for

recording weight was 10 gms and, 1 mm for length and HC. All the

measurements were taken twice and average of these observations was

recorded. However, if there was a large discrepancy between two readings

(defined as more than 5%), repeat measurements were taken. The maximum

weight loss was calculated from the difference of minimum weight and birth

weight. The age at maximum weight loss and time taken to regain

birthweight were also calculated. For calculation of daily weight gain,

period from regaining birthweight to discharge was used as denominator.

Fluid and nutrition policy: VLBW infants were

started on 80 mL/kg/d (60-120 mL/kg/d) of fluid on first day of life. The

total fluid intake was regulated to allow physiological weight loss.

Enteral feeds were initiated as soon as possible, preferably on first day

of life, if haemodynamically stable. Increments of 20-30 mL/kg/d were made

as tolerated. Human milk was preferred and once infants reached an enteral

intake of 100mL/kg/d, human milk fortifier (Lactodex HMF, manufactured by

Raptakos, Brett & Co, with 6.5 Calories, 0.2 g protein and 0.1 g fat in

each sachet) were added to increase the calories to 80 kcal/100ml with an

additional protein intake of 0.6g/kg/d. However if human milk was not

available, a low birth weight infant formula (Dexolac special care,

manufactured by Wockhardt Ltd, Mumbai, India) was used with a calorie

content of 80 kcal/100ml and 2.67g of protein in 100ml of reconstituted

formula. Infants who were not expected to be on total enteral feeds within

first 5 days of life, were started on parenteral nutrition (PN) on first

day with protein and lipid intake of 1g/kg/d. Daily increments of 1g/kg/d

were made with a maximum intake of 3 g/kg/d, targeting a parenteral

calorie intake of 90 kcal/kg/d.

Statistical methods: The Z scores for

weight, length and HC for each gestation were calculated based on means

and standard deviations from Fenton’s reference data(5,6). Infants were

classified SGA if the birth weight was below 10th centile as per Fenton’s

growth charts. Mean Z scores for weight, length and HC of the whole

cohort, were compared at birth and discharge. Similar comparisons were

made between SGA and AGA infants. For further analysis, the cohort was

classified into three gestational age groups; less than 30 weeks, 30-34

weeks and more than 34 weeks. The infants were also categorized by 100g

birthweight intervals and their weight, length and HC during the hospital

stay were plotted on the Ehrenkranz growth curves for comparison(7). SPSS

version 13.0 was used for statistical analysis. Continuous variables were

compared using student t test or Mann Whitney U test as per the

distribution of data. Paired observations were compared by paired t test

or equivalent non parametric test, as applicable.

Results

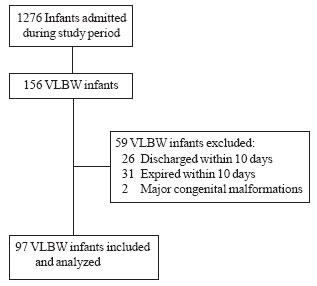

Enrolment and characteristics of the study population

including prenatal factors and neonatal morbidities are depicted in

Fig. 1 and Table I, respectively. Table II

depicts the average increase in weight, length and HC for different

gestational age categories.

|

|

Fig. 1 Study flow chart. |

TABLE I

Characteristics of VLBW infants (N = 97)

|

Maternal factors |

|

|

gestational hypertension, n (%) |

52 (53.6) |

|

gestational diabetes / IDM, n (%) |

3 ( 3.1) |

| Birth weight, mean (SD) g |

1257 (190.7) |

| Gestational age, mean (SD) wk |

31.7 (2.35) |

| Male, n(%) |

57 (58.8) |

| Infants < 30 weeks (n=25): AGA, n(%) |

25 (100) |

|

Infants 30-34 weeks (n=56) |

|

|

AGA, n (%) |

25 (44.6) |

|

SGA, n (%) |

31 (55.4) |

| Infants >34 weeks (n=16); SGA, n (%) |

16 (100) |

| Respiratory distress, n (%) |

58 (59.7) |

| Culture positive sepsis, n (%) |

28 (28.9) |

| Weight at discharge, mean (SD) g |

1695 (158.9) |

| Gestation at discharge, mean (SD) wk |

36.35 (2.45) |

| Hospital stay, median (range) d |

27 (11-105) |

TABLE II

Growth Pattern in VLBW Infants During Hospital Stay

| |

< 30 wk |

30 – 34 wk |

> 34 wk |

Total |

| |

(all AGA) |

AGA |

SGA |

(all SGA) |

AGA |

SGA |

| |

(n=25) |

(n=25) |

(n=31) |

(n=16) |

(n=50) |

(n=47) |

| Maximum

weight loss (%) |

7.3 (4.5) |

6.8 (3.2) |

6.6 (3.7) |

5.24 (3.07) |

7.1 (3.8) |

6.1 (3.5) |

| Age to

regain birthweight (d) |

10.2 (4.4) |

9.8 (3.1) |

8.8 (3.5) |

8.56 (3.72) |

10.0 (3.7) |

8.7 (3.5) |

| Weight

gain (g/kg/d) |

16.0 (20.3) |

14.8 (4.6) |

13.3 (7.9) |

18.30 (6.6) |

15.3 (14.6) |

14.9 (7.8) |

| HC

increment (cm/wk) |

0.45 (0.21) |

0.45 (0.24) |

0.50 (0.30) |

0.53 (0.29) |

0.45 (0.22) |

0.51(0.29) |

| Length

increment (cm/wk) |

0.53 (0.33) |

0.59 (0.46) |

0.70 (0.45) |

0.51(0.32) |

0.56 (0.39) |

0.63 (0.42) |

|

* VLBW: very low birth weight; AGA: appropriate for gestational

age; SGA: small for gestational age; *Difference between AGA and SGA

infants for all parameters was not significant (P > 0.05); All values

are show as mean (SD); HC: head circumference. |

|

|

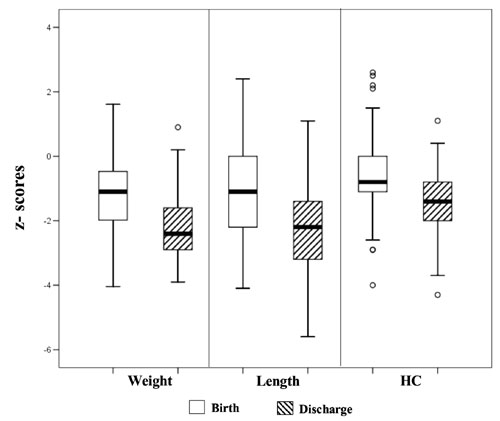

Fig. 2 Box and Whisker plot for z scores

for weight, length and HC in VLBW infants. Solid line in the box

shows median, top and bottom of the box are the interquartile range

with the range of the data. |

The mean Z scores for weight, length and HC at

birth in all subjects as calculated from the data from Fenton’s

references, were –1.17, –1.09 and –0.54, respectively. These decreased to

–2.16, –2.24 and –1.35, respectively by discharge (Fig. 2).

The mean fall in Z scores for each parameter from birth to

discharge were significantly lower in SGA as compared to AGA infants (P<0.01).

TABLE III

Characteristics and Growth Velocity of VLBW Infants as 100 g Birthweight Category

| Category

(n) |

Birthweight |

GA |

Mean weight gain (SD) |

HC increment |

Length

increment |

| |

(g) |

(wk) |

g/d |

g/kg/d |

cm/wk |

cm/wk |

| |

mean (SD) |

mean (SD) |

|

|

mean (SD) |

mean

(SD) |

| Overall

(97) |

1257 (190.7) |

31.72 (2.3) |

22.58(17.1) |

15.18 (1.7) |

0.48 (0.2) |

0.60

(0.4) |

| 701- 800

(1) |

760 |

26.71 |

6.47 |

6.60 |

0.27 |

0.45 |

| 801-900

(3) |

853.3 (45.4) |

29.81 (2.4) |

15.80(2.6) |

12.50 (1.88) |

0.44 (0.13) |

0.66

(0.27) |

| 901-1000

(5) |

951.0 (24.6) |

30.09 (2.16) |

15.11(3.82) |

11.42 (2.92) |

0.37 (0.13) |

0.40

(0.21) |

| 1001-1100

(15) |

1051.7 (27.1) |

30.05 (2.12) |

27.41(36.26) |

19.48 (25.73) |

0.48 (0.24) |

0.54

(0.24) |

| 1100-1200

(14) |

1152.7 (23.1) |

31.29 (1.57) |

18.60(4.78) |

13.15 (3.25) |

0.45 (0.18) |

0.58

(0.36) |

| 1201-1300

(12) |

1258.3 (33.8) |

33.70 (2.47) |

22.60(4.42) |

15.25 (2.41) |

0.53 (0.20) |

0.82

(0.44) |

| 1301-1400

(16) |

1351.8 (33.1) |

32.06 (2.09) |

19.80(11.33) |

13.11 (7.91) |

0.46 (0.32) |

0.54

(0.33) |

| 1401-1500

(31) |

1457.9 (31.4) |

32.53 (1.96) |

25.71(13.49) |

16.21(8.59) |

0.51 (0.31) |

0.61

(0.53) |

|

GA: Gestation at Birth, g/d: weight gain in gram/day after

regaining birthweight, g/kg/d: weight gain/kg/day after regaining

birthweight. |

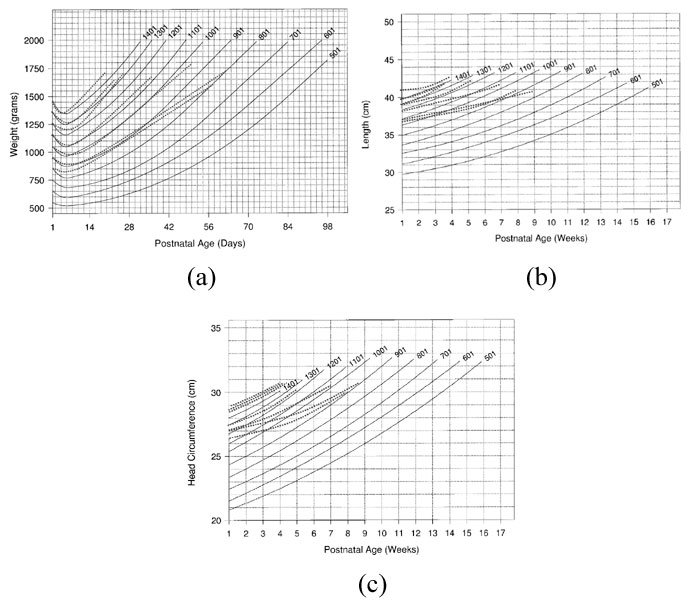

Infants were categorized by 100 g birth weight

intervals. Their gestation, birth weight, and growth velocity in each of

these categories is depicted in Table III. Maximum weight

loss, time taken to regain birth weight and later weight gain pattern

followed the Ehrenkranz postnatal growth curves except in infants with

birth weight below 1000 g who experienced slower growth (Fig. 3)(7).

The length and HC in this cohort were higher at birth and fell well below

respective reference lines by discharge, except in infants with

birthweight more than 1200g.

|

|

Fig. 3 Postnatal growth of VLBW infants

categorized by 100g birth weight superimposed on reference growth

curves. Bold lines are reference lines and dotted lines are growth

pattern of study subjects. Adapted from Longitudinal growth of

hospitalized very low birth weight infants. (1999)(7). The lowest

dotted line indicates infants with birth weight between 801 – 900g

and each of above lines with 100g weight difference. a – Weight, b –

Length, c - HC.

Reproduced with permission from Pediatrics 1999; 104: 280-289.

Copyright (e) by AAP. |

Discussion

Infants in our study were smaller at birth in all three

parameters as compared to Fenton’s intrauterine growth references. This

difference could be due to racial and ethnic factors or due to nutritional

and life style differences in this population. Lower birth Z scores

for weight and length as compared to HC suggest brain sparing growth

restriction in this cohort. These infants exhibited slow growth during

hospital stay as indicated by a fall of approximately one Z score

in each of the three parameters from birth to discharge. This observation

is similar to the decline reported by Hack, et al.(1) in

VLBW infants from birth to 40 weeks.

With the nutritional practices used in this study, our

infants experienced a daily weight gain of 15.18+1.7 g/kg/d, which

is comparable to intra-uterine growth rate and other reports. However, the

weekly increments in HC and length were almost half of the intrauterine

growth expectations and other reports(7-9). This discrepant growth could

be due to relatively more accumulation of body fat as com-pared to muscle

mass and bone growth. Larger proportion of SGA infants in this study may

have contributed towards this trend. Whether this is due to variation in

quality and composition of low birth-weight feeding-formula, human milk

fortifiers, or due to poor growth potential of SGA infants in this ethnic

group, needs to be investigated.

Since most VLBW infants do not achieve intrauterine

growth rates during postnatal life, it seems more appropriate to monitor

their growth on postnatal charts. When we plotted the growth of our

infants on Ehrenkranz’s charts, it matched reference lines for each 100g

category, except in those below 1000g at birth(7). This could be due to

higher morbidity in extremely low birth weight infants in the present

setting. Growth comparable to these references in infants above 1200g is

possibly due to better maturity and feed tolerance, and lesser neonatal

morbidity. Higher length and HC at birth in each 100g category could be

due to higher gestational age in our cohort as compared to NICHD data(7).

However, even in these parameters, weekly increments were less than

expected(5,7).

SGA infants are at double jeopardy; in addition to

intrauterine growth restriction, many are born pre-maturely(10). They

continue to grow slow during early postnatal life(11,12). We noted that

both AGA and SGA infants had a significant drop in their growth Z

scores during hospital stay. Even though SGA infants experienced lesser

fall in their growth parameters as compared to AGA, they did not exhibit

desired catch up growth during hospital stay and continued to grow at a

lower trajectory. Both SGA and AGA VLBW infants in our study had

comparable growth velocity during hospital stay. This is in contrast to an

earlier observation which reported faster weight gains in SGA infants(7).

This could possibly be due to more growth restriction or poor growth

potential of SGA infants in our study popu-lation. Further analysis of a

category of infants bet-ween 30-34 weeks, which had comparable number of

SGA and AGA infants, revealed similar growth trends.

Slower brain growth during infancy is a predictor of

poor neurodevelopment outcome and has been shown to be associated with

poor school performance(13,14).

Smaller increments in HC during hospital stay in this cohort is a cause

for concern and there is a need for continued follow up of these infants

to monitor for catch up in head growth, along with their cognitive and

learning abili-ties. VLBW infants in this study also experienced slower

linear growth during hospital stay. They need a long term follow up for

catch up, as poor growth during early infancy has been shown to be

associated with persistent stunting in later life(15).

This study highlights the growth trends of VLBW infants

in a setting where incidence of low birth weight and growth restriction is

high. The disproportionate postnatal

growth pattern observed in this study may reflect altered body composition

with increased fat and lesser lean body mass, which may predispose them to

metabolic syndromes(16). This observation needs further validation, to

know the real growth potential of VLBW infants from this subcontinent. The

limitations of this study are small sample size, recruitment from a single

centre, and comparison of their growth with references from ethnically

different population. Another limitation is that almost 17% of the VLBW

infants were not available for follow up.

Contributors: SS and MM were responsible for the

study idea, design, data collection and analysis. AK and AB helped in data

collection and analysis. AS and PG helped in editing manuscript. NK

supervised and helped in review and editing the manuscript. All authors

approved the final content of the manuscript.

Funding: None.

Competing interest: None stated.

|

What is Already Known?

•

VLBW infants suffer growth lag during early postnatal period.

What This Study Adds?

• A

disproportionate growth was found in the VLBW infants studied.

|

References

1. Hack M, Schluchter M, Cartar L, Rahman M, Cuttler L,

Borawski E. Growth of very low birth weight infants to age 20 years.

Pediatrics 2003; 112: 30-38.

2. Astbury J, Orgill AA, Bajuk B, Yu VYH. Sequelae of

growth failure in appropriate for gestational age, very low birth weight

infants. Dev Med Child Neurol 1986; 28: 472-479.

3. Lundgren EM, Cnattingius S, Jonsson B, Tuvemo T.

Intellectual and psychological performance in males born small for

gestational age with or without catch-up growth. Pediatr Res 2001; 50:

91-96.

4. Hajnal BL, Siebenthal KV, Kovari H, Bucher HU, Largo

RH. Postnatal growth in VLBW infants: Significant association with

neurodevelopmental outcome. J Pediatr 2003; 143: 163-170.

5. Fenton TR. A new growth chart for preterm babies:

Babson and Benda’s chart updated with recent data and a new format. BMC

Pediatr 2003; 3: 13-22.

6. Fenton TR. Preterm Growth Chart 2003 calculations.

Available from http://members. shaw.ca/growthchart/Fenton Growth Chart

calculations.xls. Accessed on 10 February, 2009.

7. Ehrenkranz RA, Younes N, Lemons JA, Fanaroff AA,

Donovan EF, Wright LL. Longitudinal growth of hospitalized very low birth

weight infants. Pediatrics 1999; 104: 280-289.

8. American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on

Nutritional Needs of Low-Birth-Weight Infants. Pediatrics 1977; 60:

519-530.

9. American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on

Nutritional Needs of Low-Birth-Weight Infants. Pediatrics 1985; 75:

976-986.

10. Gutbrod T, Wolke D, Soehne B, Ohrt B, Riegel K.

Effects of gestation and birth weight on the growth and development of

VLBW small for gestational age infants: A matched group comparision. Arch

Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2000; 82: F 208-214.

11. Bertino E, Coscia A, Boni L, Rossi C, Martano C,

Giuliani F, et al. Weight growth velocity of very low birth weight

infants: role of gender, gestational age and major morbidities. Early Hum

Dev 2009; 85: 339-347.

12. Radmacher PG, Looney SW, Rafail ST, Adamkin DH.

Prediction of extrauterine growth retardation (EUGR) in VVLBWI. J

Perinatol 2003; 23: 392-395.

13. Powls A, Botting N, Cooke RWI, Pilling D, Marlow N.

Growth impairment in very low birthweight children at 12 years:

correlation with perinatal and outcome variables. Arch Dis Child 1996; 75:

F152-F157.

14. Hack M, Breslau N, Weissman B, Aram D, Klein N,

Borawski E. Effect of very low birth weight and subnormal head size on

cognitive abilities at school age. N Engl J Med 1991; 325: 231-237.

15. Knops NBB, Sneeuw CAK, Brand R, Hille ETM, Ouden

AL, Wit JM, et al. Catch-up growth up to ten years of age in

children born very preterm or with very low birth weight. BMC Pediatr

2005; 5: 26-34.

16. Yajnik CS, Fall CHD, Coyaji KJ, Hirve SS, Rao S,

Barker DJP, et al. Neonatal anthropometry: the thin-fat indian

baby. The Pune Maternal Nutrition Study. Int J Obes 2003; 27: 173-180.

|

|

|

|

|