|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2009;46: 849-854 |

|

Physical Work Capacity of Young

Underprivileged School Girls: Impact of Daily vs Intermittent

Iron-Folic Acid Supplementation – A Randomized Controlled

Trial |

|

A Sen and SJ Kanani

From Department of Foods and Nutrition, The Maharaja

Sayajirao University of Baroda, Vadodara, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Shubhada Kanani, 14, Anupam

Society, Behind Pizza Inn, Jetalpur Road, Vadodara, India.

E-mail: [email protected]

|

|

Abstract

Objectives: To assess impact of daily and

intermittent iron-folate (IFA) supplementation on physical work capacity

of underprivileged schoolgirls in Vadodara.

Design: Randomized controlled trial.

Setting: Municipal Primary schools.

Participants: Schoolgirls (n=163) in the

age group of 9-13 years.

Intervention: Three randomly selected schools

were given IFA tablets (100 mg elemental iron + 0.5 mg folic acid)

either once weekly or twice weekly or daily for one year. The fourth was

the control school.

Outcome Measures: Hemoglobin, modified Harvard's

Step test for physical work capacity.

Results: All three IFA supplemented groups showed

significant improvement in number of steps climbed and recovery time

compared to controls; with impact being relatively better in girls with

higher Hb gain (>1 g/dL) vs. lower Hb gain. Similarly, higher the

frequency of dosing better was the impact- it being the best in daily

IFA group. Twice weekly IFA was as good as daily IFA under conditions of

good compliance.

Conclusion: Twice weekly IFA supplementation is

comparable to daily IFA in terms of beneficial effects on physical work

capacity in young girls.

Keywords: Anemia, Iron-folate supplementation, Physical work

capacity, School girls.

|

|

B

esides being a major threat to safe

motherhood, iron deficiency anemia (IDA) in adolescent girls contributes

to poor growth, lowered resistance to infections, poor cognitive

development and most importantly, decreased work capacity(1). In IDA,

physical work capacity (PWC) is compromised due to decrease in hemoglobin,

which reduces the availability of oxygen to the tissues, and hence certain

tissues and organs that require much oxygen like heart may suffer,

resulting in diminished capacity to perform energy consuming tasks(1,2).

The concentration of myoglobin in skeletal muscle is reduced limiting the

rate of diffusion of oxygen from erythrocytes to mitochondria(1). Thus,

work output, endurance and maximal work capacity are impaired in iron

deficient states.

To combat anemia, initiation of iron supplementation in

the adolescent years has been recommended. Once weekly administration of

iron-folate (IFA) supplements given to adolescent school girls under

supervised conditions has been found to be effective and practical for

raising hemoglobin levels among girls in Indian studies(3-4). Daily IFA

has also shown positive impact on growth of school children and

adolescents(5-6). However, little is known about the benefits of IFA

supplementation on physical work capacity of young school going

adolescents entering the pubertal growth spurt. In adolescent girls, with

high social expectations of meeting the demands of domestic work and

school, decreased PWC may compromise their quality of life. We studied the

impact of intermittent (once and twice weekly) and daily IFA

supplementation on physical work capacity of underprivileged schoolgirls

in early adolescence (9-13 years) in Vadodara.

Methods

This was an experimental-control semi-longitudinal

study; an efficacy trial to assess impact of iron folic acid supplements

on physical work capacity. Prior permission from the Primary School Board,

Vadodara, and informed written consent from students and their parents

were taken. The departmental ethical committee cleared the study.

Sampling: Using accepted procedures, desired sample

size was calculated(7); which came to 46 per group. Allowing for dropouts,

each study group required about 60 subjects of age 9-13 years; which were

available in standards V and VI per school. Thus, four schools were

randomly selected from a sampling frame of 17 schools (all Municipal

primary schools for girls in the morning shift), and all consenting girls

studying in Standards V and VI were enrolled. Students in all four schools

had similar socioeconomic, home and school environment.

Intervention: Three schools were randomly selected

as experimental schools (ES) and were given IFA tablets (100 mg elemental

iron +0.5 mg folic acid) either once weekly (IFA-1Wkly) or twice weekly

(IFA-2Wkly) or daily (IFA-Daily) for one year. The fourth was the control

school (No-IFA). Girls were not dewormed prior to the intervention. The

investigators, with assistance from the class teachers / monitors, ensured

regular supervised distribution and compliance of IFA in all intervened

schools. The tablets were distributed immediately after the tiffin break

(short recess) to ensure they were not taken on empty stomach.

Data collection: Pre and post

intervention hemoglobin data were collected on all girls. In view of the

limited working school days and the time required to conduct physical work

capacity test, a random 60% sample (n=240) was selected. From this,

data of 163 girls was available pre and post intervention; after also

excluding girls who had attained menarche during the study, though they

did receive IFA supplements. None of the girls suffered from illnesses

which might affect work capacity except one girl, who had asthma and was

unwilling to participate. Further, none of the girls was involved in

athletics/sports on a regular basis.

Outcome variables: Hemoglobin levels were assessed

using cyanmethemoglobin method(8). Physical work capacity (PWC) of the

subjects was assessed using Modified Harvard's Step test (MHST)(9); which

has been used in earlier studies on school children in the department and

found to be valid(10). The girls were asked to climb up and down a set of

five steps as fast as they could for three minutes. The total number of

steps climbed up and down was counted. The resting pulse rate was recorded

manually before the girls began the test. Post exercise, the time taken

(minutes) to revert to the basal pulse rate was also recorded (recovery

time). Means and standard deviations were calculated for hemoglobin and

PWC. The mean change in each group was calculated and compared between the

experimental groups and also with the control group. Girls with good

compliance were defined as those who consumed atleast 70% tablets

distributed. To compare various intervention groups for statistical

significance of impact (P<0.05), ANOVA test and to compare each

group with control, students t test was used. All the data were

coded, entered and analyzed in Epi Info, Version 6.04-d.

Results

Mean baseline Hb was similar in all groups (P>0.05);

being 11 to 11.5 g/dL. Post intervention, all intervention groups had

significantly higher mean Hb increment vs. controls, with increment being

highest in IFA-2Wkly (0.97 g/dL) followed by IFA-Daily group (0.93 g/dL).

IFA-1Wkly showed the lowest increment (0.62 g/dL). However, among the

initially anemic girls (Hb<12 g/dL), IFA-Daily group showed highest

increment (1.9 g/dL) followed closely by IFA-2Wkly (1.6 g/dL).

Impact on Physical Work Capacity

Number of Steps Climbed: The mean

increase in number of steps climbed was significantly higher (and almost

twice as high) among supplemented groups (21 to 29 steps) compared to

controls (13 steps) (Table I). Within the supplemented

groups, IFA-Daily girls had significantly higher (P<0.05) increase

in number of steps climbed than IFA-1Wkly. IFA-Daily was followed closely

by IFA-2Wkly; least impact was seen in IFA-1Wkly.

TABLE I

Change in Mean Number of Steps Climbed and Recovery Time-RT (in min) After the Intervention

|

Study Groups |

N |

Increase in Number |

Recovery |

| |

|

of Steps Climbed |

Time |

| |

|

(Mean ± SD) |

(Mean ± SD) |

| IFA-1Wkly

|

43 |

21 ± 13.53 |

–0.12 ± 0.73 |

| IFA-2Wkly

|

42 |

27 ± 21.33 |

–0.17 ± 0.73 |

| IFA-Daily

|

44 |

29 ± 15.61 |

–0.48 ± 0.73 |

| No-IFA

|

34 |

13 ± 16.26 |

0.06 ± 0.60 |

| F test |

|

P<0.001 |

P<0.01 |

|

•Comparing each experimental group (EG) with control:

Increase in steps climbed- all EG were significantly better (IFA-1Wkly

P<0.05; IFA 2Wkly P<0.01, IFA-Daily P<0.001); RT: only IFA-Daily was

significant (P<0.001).

•Within experimental groups: Increase in steps climbed

and RT improvement; IFA-Daily was significantly better than IFA-1Wkly

(P<0.05). |

Recovery time: The improved recovery time (RT), was

significantly better in IFA-Daily than No-IFA group (Table I).

Although there was decrease in RT in IFA-2Wkly and IFA-1Wkly, this was not

significantly better than No-IFA. There was slight increase in the RT of

the girls in No-IFA group.

Influence of compliance with IFA: In

each treated group, girls with good compliance showed better impact than

those with poor compliance and this difference was significant in IFA-Daily.

Within good compliance, comparing the groups, the increment in number of

steps climbed or recovery time was the best in IFA-Daily but between

groups, differences were not significant (Table II).

However, within poor compliance, between-group difference was significant,

with IFA-Daily showing best impact and IFA-1Wkly showing least impact

(increase in RT).

TABLE II

Number of Steps Climbed and Recovery Time (in min) After MHST in

Girls With Good Compliance and Poor Compliance

| |

|

Good Compliance1 |

|

Poor Compliance2 |

'P' |

Study

Groups |

N |

Initial |

Final |

Mean

change

(A) |

N |

Initial |

Final |

Mean

change

(B) |

Value

A vs B |

|

Number of Steps Climbed (Mean ± SD) |

| IFA-1Wkly

|

26 |

171±28.27 |

195±24.43 |

24±14.34 |

17 |

166±20.03 |

184±20.56 |

18±11.06 |

>0.05 |

| IFA-2Wkly

|

30 |

181±40.56 |

208±31.48 |

29±24.69 |

12 |

178±39.57 |

201±30.24 |

23±15.05 |

>0.05 |

| IFA-Daily

|

27 |

188±32.59 |

221±28.71 |

34±14.35 |

15 |

191±34.45 |

212±2 5.18 |

22±15.77 |

<0.05 |

| P Value |

|

|

|

>0.05 |

|

|

|

>0.05 |

|

|

Recovery time (RT) (Mean ± SD) |

| IFA-1Wkly |

26 |

3.88±0.86 |

3.50±0.94 |

–0.38±0.69 |

17 |

3.88±0.78 |

4.17±0.08 |

0.29±0.58 |

<0.01 |

| IFA-2Wkly

|

30 |

2.76±1.07 |

2.53±0.63 |

–0.23±0.77 |

12 |

2.75±0.75 |

2.75±0.75 |

0.00±0.60 |

<0.05 |

| IFA-Daily

|

27 |

3.29±0.95 |

2.59±0.64 |

–0.70±0.77 |

15 |

2.46±0.64 |

2.26±0.59 |

–0.20±0.41 |

<0.05 |

| P Value |

|

|

|

>0.05 |

|

|

|

<0.05 |

|

Values are Mean ± SD; 1Compliance of 70% of IFA dose, 2Compliance of < 70% of IFA dose.

|

Hemoglobin gain and physical work capacity

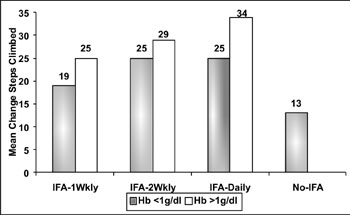

Figure 1 shows that the mean increase in the

number of steps climbed was higher among those who gained Hb levels

³1

g/dL compared to those with Hb increase <1 g/dL, the difference being

significant in IFA-2Wkly and IFA-Daily groups. In the group which gained

³1

g/dL Hb, the increase in number of steps climbed was highest in IFA-Daily,

(which was significantly better than IFA-1Wkly group), followed by

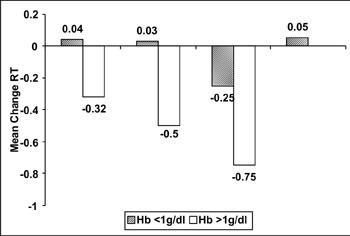

IFA-2Wkly. On comparing the change in the recovery time, it was clear the

decline in the RT was higher amongst those with higher Hb increments (Fig.2).

Further, more frequent the dosing, better the impact. The trends were

similar when only good compliance girls were considered.

|

|

| Fig. 1 Mean

change in steps climbed - girls with Hb gain>1 g/dL vs. girls with

Hb gain< 1g/dL. |

Fig. 2 Mean

change in recovery time- girls with Hb gain>1 g/dL vs. girls with Hb

gain <1g/dL. |

Initial level of anemia and physical work capacity

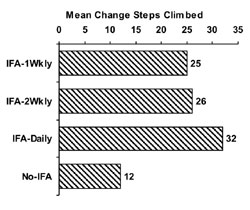

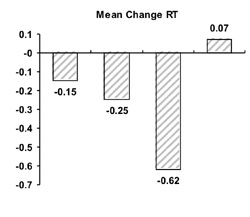

Considering only anemic girls (Hb <12 g/dL), the mean

increase in the number of steps climbed in all intervened groups was

significantly better than in controls (Fig. 3). Within the

intervened groups, increase in number of steps in IFA-Daily was

significantly higher than in IFA-1Wkly. The differences in the increase in

steps among anemic girls in IFA-2Wkly and IFA-1Wkly were non-significant.

In terms of change in recovery time, only those who received daily doses

and were initially anemic showed significant decrease in the RT compared

to No-IFA. Therefore, daily supple-mentation of iron folate tablets

significantly improved the work capacity among anemic girls in terms of

increase in number of steps climbed and decrease in recovery time.

|

|

| Fig.

3 Number of steps climbed and recovery time in initially

anemic girls after the intervention. |

Discussion

The findings of this study indicate that among the

intervention groups (as compared to controls), the IFA-Daily group showed

the maximum impact followed by IFA-2Wkly as regards improvement in PWC in

terms of significantly higher increase in the number of steps climbed and

improvement (reduction) in recovery time (RT). IFA-1Wkly showed least

impact; though it was better than control. These trends remained when

subgroups like ‘girls with good compliance’, and ‘anemic girls’ were

considered. Girls who gained more Hb (>1 g/dL) showed better improvement

in PWC vs. those who gained Hb<1 g/dL; in all treated groups.

Higher the frequency of IFA supplementation (daily and twice weekly),

better the improvement in hemoglobin and PWC.

Data on impact of IFA on PWC among school children and

adolescents is scanty in literature. Supplementation of 60 mg iron per day

to non-pregnant female workers in Beijing reduced mean heart rate, and

increased the production efficiency. Iron supplementation enabled the

female workers to do the same work at lower energy cost(11). A randomized

double-blind placebo-controlled trial has been reported in Sri Lanka(12)

on 20-60 years old female tea estate workers. The first study group

received 200 mg FeSO4 for 1 month and the second study group received 200

mg FeSO4 for 3 wks. There was a net increase of 1.5 g/dL in Hb level. The

amount of tea picked increased by 1.2%. The heart rates were significantly

lower after supplementation. In South India, young adult women given 60 mg

of iron for 100 days showed reduced energy expenditure for physical

activities like walking, running, climbing, skipping and sweeping. The

mean distance covered by anemic women while walking increased from 8

meters/min to 14 meters/min after iron supplementation. The exertion on

heart as shown through blood pressure and pulse rate, also reduced after

supplementation(13).

In rural Varanasi, UP, India, a study on school

children (6-8 years) over one year (170 working days) assessed the impact

of iron supplementation (Iron syrup: ferrous gluconate 200 mg) on physical

growth, physical stamina, mental function and academic performance(14) and

reported that the supplementation did not influence the performance of

children on the parameters of Harvard step test; but mean scores for

recovery period were better for the supplemented group than controls after

a 300 meter run-cum-walk. Studies conducted in this department in Vadodara

using Modified Harvard Step Test to assess the work performance of anemic

preschool children(15) and using indicators like increase in the number of

skips done by school girls with a skipping rope reported a significant

improvement in PWC of iron treated subjects compared to controls(10).

Our study has shown that while once-weekly IFA may not

suffice; twice weekly IFA has the potential to lead to significant

improvement in physical work capacity at less cost and greater feasibility

as compared to daily IFA supplements; this however needs to be further

explored through randomized control trials on larger samples. Another

important observation emerging from this study is that IFA supplementation

should be initiated not just in secondary schools as at present is the

case in Gujarat, but earlier in primary school (classes V-VII) when

children are entering adolescence and when iron demands are high for

growth and development.

Contributors: AS collected, analysed and

interpreted the data and performed literature review and drafted the

manuscript. SJK designed the study, supervised data collection, analysis.

She also revised and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None stated.

|

What is Already Known?

• Daily and once-weekly iron-folate

supplementation improve hemoglobin levels among adolescent girls.

What This Study Adds?

• Intermittent iron folate supplementation (daily

and twice weekly) significantly improves work capacity and decreases

recovery time among school girls compared to once weekly and anemic

girls benefit more from Daily IFA supplementation.

|

References

1. Beaton GH, Corey PN, Steele C. Conceptual and

methodological issues regarding the epidemiology of iron deficiency and

their implications for studies of the functional consequences of iron

deficiency. Am J Clin Nutr 1989; 50: 575-588.

2. Bothwell TN, Carlton RW, Cook JD, Finch CA. Iron

Metabolism in Man. 1st edition. England. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific

Publication; 1979.

3. Agarwal KN, Gomber S, Bisht H, Som M. Anemia

prophylaxis in adolescent school girls by weekly or daily iron-folate

supplementation. Indian Pediatr 2003; 40: 296-230.

4. Kotecha RV, Patel RZ, Karkar PD, Nirupam S. Impact

evaluation of adolescent girl's anemia reduction program Vadodara

district. Government of Gujarat, India. 2002.

5. Kanani S, Poojara RM. Supplementation with IFA

enhances growth in adolescent Indian girls. J Nutr 2000; 130: 452S-455S.

6. Lawless JW, Latham MC, Stephenson LS, Kinoti SN,

Pertet AM. Iron supplementation improves appetite and growth in anemic

Kenyan primary school children. J Nutr 1994; 124: 645-654.

7. Fisher AA, Laing J, Stoeckel J, Townsend JW.

Handbook for Family Planning, Operations Research Design. 2nd edition. New

York: The Population Council; 1991.

8. International Nutritional Anemia Consultancy Group.

Guidelines for eradications of iron deficiency anemia. A report of

international nutritional anemia consultancy group (INACG). New York and

Washington DC: INACG; 1985.

9. Skubic V, Hodgkins J. Cardiovascular efficiency test

scores for junior and senior high school girls in the United States. Res Q

1964; 35: 184-192.

10. Kanani S, Singh P, Zutshi R. The impact of daily

iron vs. calcium supplementation on growth, physical work capacity and

mental functions of school going adolescent boys and girls (9 to16 yrs) of

Vadodara. Department of Foods and Nutrition, The M. S. University of

Baroda, Vadodara, India. 1999.

11. Li R, Chen X, Yan H, Deurenberg P, Garby L,

Hautvast JG. Functional consequences of iron supplementation in

iron-deficient female cotton mill workers in Beijing China. Am J Clin Nutr

1994; 59: 908-913.

12. Edgerton VR, Gardner GW, Ohira Y, Gunawardena KA,

Senewiratne B. Iron-deficiency anemia and its effect on worker

productivity and activity patterns. Br Med J 1979; 2: 1546-1549.

13. Vijayalakshmi P, Selvasundari S. Relationship

between iron deficiency anemia and energy expenditure of young adult

women. Indian J Nutr Dietet 1983; 20: 113-117.

14. Agarwal DK, Upadhyay SK, Tripathi AM, Agarwal KN.

Nutritional status, physical work capacity and mental function in school

children. New Delhi: Nutrition Foundation of India; 1987.

15. Seshadri S, Malhotra S. Effect of hematinics on physical work

capacity in anemics. Indian Pediatr 1984; 21: 529-533.

|

|

|

|

|