|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2021;58:1059-1066 |

|

Factors Associated With Neonatal Pneumonia

and its Mortality in India: A Systematic Review and

Meta-Analysis

|

|

N Sreekumaran Nair, 1

Leslie Edward Lewis,2 Vijay

Shree Dhyani,1 Shruti

Murthy,1 Myron Godinho,1

Theophilus Lakiang,1 Bhumika

T Venkatesh1

From 1Department of Statistics, Public Health Evidence South Asia

(PHESA); and 2Department of Pediatrics, Kasturba Medical College

Hospital; Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Karnataka.

Correspondence to: Dr Bhumika T Venkatesh, Room no. 35,

Public Health Evidence South Asia (PHESA), Prasanna School of Public

Health, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Madhav Nagar, Manipal,

Karnataka.

Email:

[email protected]

Received: May 19, 2020;

Initial review: June 29, 2020;

Accepted: March 13, 2021.

Protocol registration: PROSPERO 2016 CRD42016044019 (risk

factors);

PROSPERO 2016 CRD42016045398 (mortality)

|

Background: Neonatal pneumonia remains a significant contributor to

infant mortality in India and responsible for increased prevalence of

infant deaths globally. Objective: To identify risk factors

associated with neonatal pneumonia and its mortality in India. Study

design: A systematic review was conducted including both

analytic study designs and descriptive study designs, which reported a

quantitative analysis of factors associated with all the three types of

pneumonia among neonates. The search was conducted from August to

December, 2016 on the following databases; CINAHL, EMBASE, Ovid MEDLINE,

PubMed, ProQuest, SCOPUS, Web of Science, WHO IMSEAR and IndMED. The

search was restricted to Indian setting. Participants: The

population of interest was neonates. Outcomes: The outcome

measures included risk factors for incidences and mortality predictors

of neonatal pneumonia. These could be related to neonate, maternal and

pregnancy, caregiver, family, environment, healthcare system, iatrogenic

and others. Results: A total of three studies were

included. For risk factors, two studies on ventilator-associated

pneumonia were included with 194 neonates; whereas for mortality

predictors, only one study with 150 neonates diagnosed with pneumonia

was included. 11 risk factors were identified from two studies: duration

of mechanical ventilation, postnatal age, birth weight, prematurity, sex

of the neonate, length of stay in NICU, primary diagnosis, gestational

age, number of re-intubation, birth asphyxia, and use of nasogastric

tube. Meta-analysis with random-effects model was possible only for

prematurity (<37 week) and very low birth weight (<1500 g) and very low

birth weight was found to be significant (OR 5.61; 95% CI 1.76, 17.90).

A single study was included on predictors of mortality. Mean alveolar

arterial oxygen gradient (AaDO2) >250 mm Hg was found to be the single

most significant predictor of mortality due to pneumonia in neonates.

Conclusion: The study found scant evidence from India on risk

factors of neonatal pneumonia other than ventilator-associated

pneumonia.

Keywords: Alveolar-arterial oxygen gradient,

Respiratory distress, Risk factors, Ventilator-associated pneumonia.

|

|

N

eonatal pneumonia

accounts for 6.1% of total

global neonatal mortality whereas it contributes 5.1% to neonatal mortality in India and

5.6% in South Asia [1]. There is no international consensus

regarding definition, diagnostic criteria and management of

pneumonia among neonates [2, 3]. National nosocomial infections

surveillance (NNIS) 1996 and original Centers for Disease

Control (CDC) guidelines (pediatric modification) are commonly

followed for diagnosis of neonatal pneumonia.

It has been observed that poverty, limited

healthcare accessibility, and improper child-rearing practices

are some of the risk factors for pneumonia in young children

[4]. Other factors related to development of pneumonia,

particularly in India, are financial status, malnutrition, poor

immunization status, and household air pollution [5]. In South

East Asia, poor prenatal care, home delivery, fever at birth,

maternal urinary tract infections, prolonged rupture of membrane

were found as notable risk factors of neonatal pneumonia [6,7].

There is scanty information available on

neonatal pneumonia from India. Identification and elimination of

risk factors associated with neonatal pneumonia is imperative to

reduce its high prevalence and associated mortality, and

implementing appropriate interventions to improve neonatal

survival. With this review we intended to identify risk factors

and mortality predictors associated with neonatal pneumonia in

the Indian context.

METHODS

Protocol for these systematic reviews were

registered with PROSPERO [8,9] and published as separate

publications [10,11] where methodology is described in detail.

Ethical clearance was obtained from institutional ethics

committee of the host institution.

Studies reporting all types of neonatal

pneumonia published in English language in journals,

irrespective of peer reviewed or not were eligible for

inclusion. Studies on neonatal sepsis were also searched to

verify the presence or absence of a ‘pneumonia’ subgroup as

pneumonia is usually considered under the umbrella of neonatal

sepsis. To be eligible for inclusion, these articles had to

mention the outcomes specifically for neonatal pneumonia.

Both analytic study designs (case-control

studies, cohort studies, cross-sectional studies) and

descriptive study designs (case series, cross-sectional studies)

which report a quantitative analysis of factors associated with

all the three types of pneumonia among neonates were eligible

for inclusion. Letters, editorials, commentaries, reviews,

meta-analysis, qualitative research, conference papers and

reports were excluded.

Neonates diagnosed with any form of pneumonia

including community acquired pneumonia, congenital pneumonia and

hospital acquired pneumonia (ventilator associated pneumonia)

were included. The outcome measures included risk factors for

neonatal pneumonia and its mortality. These could be related to

neonate, maternal and pregnancy, caregiver, family, environment,

healthcare system, iatrogenic and others.

Search methods: Articles were

identified from nine databases (CINAHL, EMBASE, Ovid MEDLINE,

ProQuest, PubMed, SCOPUS, WHO IMSEAR, Web of Science and IndMED)

and government websites without time restriction. A separate

search was undertaken to identify risk factors and mortality

predictors associated with neonatal pneumonia. Detailed search

terms and strategy for PubMed for both the outcomes has been

provided in Web Appendix 1. The search on all the

databases was conducted from August to December, 2016. Some of

the search terms included were: "Risk factor" OR "determinant"

OR "risk" OR "predictor" AND "Mortality" OR "fatal" OR "case

fatality" OR "case fatality rate" AND "Neonate" OR "childhood"

OR "neonatal" OR "newborn" AND "Pneumonia" OR "hospital acquired

pneumonia") OR "community-acquired pneumonia" OR "ventilator

associated pneumonia" OR "early onset pneumonia" OR "late onset

pneumonia." Additionally grey literature search and snowballing

were also conducted to find out potentially relevant studies.

The authors were contacted in an attempt to retrieve missing

information on important methodological aspects or outcomes

measures.

Data extraction and quality assessment:

Considering inclusion and exclusion criteria, three review

authors (SM, MG, and TL) worked in two teams to screen, extract

data and quality assessment of identified literature. The

consensus for any discrepancies were sought through discussion

with senior reviewers (NSN, LL, and BTV). A Preferred Reporting

Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) chart

was generated to summarize the study selection process.

Characteristics were summarized and results were reported using

tables and accompanied by a descriptive summary that compared

and evaluated the methods and results of included studies. The

results of the search were managed and screened using Endnote

(v. x7). Microsoft Excel 2007 was utilized for data extraction.

Statistical analysis: Depending on

methodological hetero-geneity, a random-effects model was used.

The summary measures were pooled based on study design. A Forest

plot was generated and pooled estimates were reported with 95%

CIs. Based on the availability of data, a subgroup analysis was

also planned a priori with respect to study design, type of

neonatal pneumonia, study setting, and onset of pneumonia.

However, the subgroup analysis was not possible due to

non-availability of relevant data. For meta-analysis, data were

available only from two studies on VAP (ventilator-associated

pneu-monia) and meta-analysis was possible only for two factors

i.e., very low birth weight and prematurity. Depending on data

availability, a sensitivity analysis and meta-regression was

planned but could not be performed due to limited data.

Reporting bias could also not be assessed as included studies

were less than 10.

The reporting has been done in accordance

with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and

Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [12] and the Meta-analysis of

Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines [13].

Quality assessment was done at the study level using the

modified Quality Assessment Tool for Systematic Reviews of

Observational Studies (QATSO) tool [14]. STATA (v.13) was used

to perform statistical analyses.

RESULTS

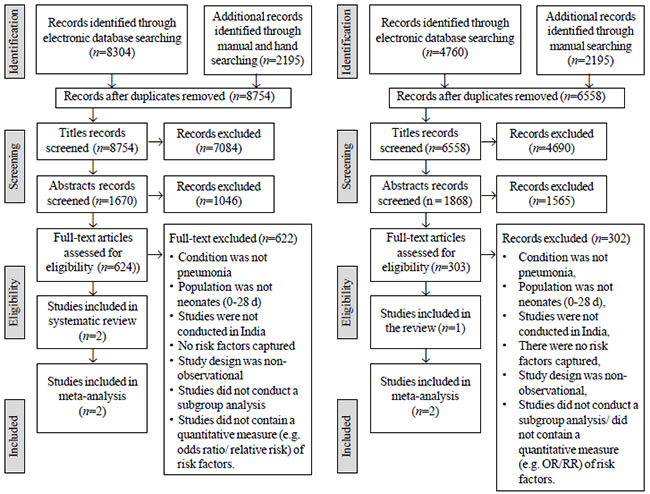

A total of 8754 citations were subjected to

title screening, and finally two articles were found to be

eligible and were included for the meta-analysis (Fig. 1).

For mortality predictors of neonatal pneumonia, a total of 6,955

citations were identified, of which, 303 articles were screened

for full text and only one article was eligible for inclusion (Fig.

2). Meta-analysis was not possible as there was only one

eligible study.

|

|

Fig. 1 PRISMA flow chart

depicting the study selection process for risk factors

of neonatal pneumonia.

|

Fig. 2 PRISMA flowchart

depicting the study selection process for factors

associated with mortality.

|

For risk factors, two studies [15,16] were

included with data from a total of 194 neonates. For mortality

predictors, only one study [17] with 150 neonates was

included. Table I lists the characteristics of included

studies [18].

Both studies used (NNIS) 1996 guidelines in

conjunction with pediatric modification of the original center

for disease control guidelines. [15,16]. Both studies (risk

factors) found Klebsiella species as the most predominantly

isolated organism from the endotracheal aspirate of neonates

with ventilator associated pneumonia. None of the studies

reported the socio-demographic characteristics of neonates with

or without ventilator associated pneumonia.

Web Table I

describes in detail diagnostic criteria used for ventilator

associated pneumonia [15,16] and neonatal pneumonia [17]. The

study on mortality predictors did not specify the guideline

followed for diagnosis of neonatal pneumonia, the authors

reported the use of the National Neonatology Forum (NNF) to

diagnose ‘respiratory problems’. In both the studies [15,16] no

primary criteria for mechanical ventilation was provided in the

methodology; however, in one of the study results indicated four

conditions for mechanical ventilation namely pneumonia, apnea,

poor respiratory effort and Hyaline Membrane Disease [15].

In total, 11 risk factors were identified

from two studies and six of them were common across both

studies. Table I provides a risk factor profile of the

included studies [15, 16]. A random effects model was used for

the meta-analysis. Meta-analysis was carried out for only two

factors from two studies namely very low birthweight (VLBW) and

prematurity. In both the included studies, a significant

association was found between development of ventilator

associated pneumonia and duration of mechanical ventilation and

number of re-intubations; however, there was missing data and

attempts at reaching the authors were unsuccessful, therefore a

meta-analysis could not be performed for these factors.

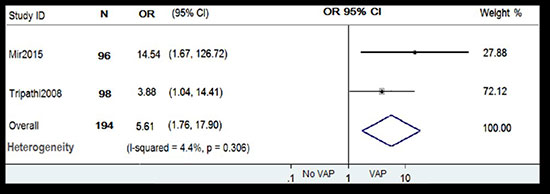

Pooled OR for very low birth weight from

random effects meta-analysis of two studies [15,16] is depicted

in Fig. 3. The forest plot show that neonates with VLBW

(<1500 g) were more likely to develop ventilator associated

pneumonia compared to neonates who were normal to low

birthweight (OR 5.61; 95% CI 1.76, 17.90). Very low birth weight

was found to be significant risk factor for development of

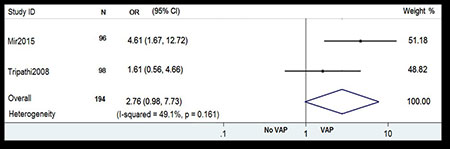

ventilator associated pneumonia. Pooled OR for prematurity is

depicted in Fig. 4 [15, 16]. The Forest plot shows

that neonates with estimated gestational age <37 week or

premature neonates were more likely to develop ventilator

associated pneumonia compared to term neonates (OR 2.76; 95% CI

0.98, 7.73).

|

|

Fig. 3 Forest plot showing the

effect of very low birthweight on ventilator-associated

pneumonia.

|

|

|

Fig. 4 Forest plot showing the

effect of prematurity on ventilator-associated

pneumonia.

|

Only one study [17] reported mortality

predictors to neonatal pneumonia. The authors did not specify

the list of independent and confounding variables considered as

predictors for fatality due to pneumonia in neonates. However,

they provided only P values for significant predictors

which they considered for multiple logistic regression. These

predictors included: <birthweight 2000 g, gestation <34 week,

age at presentation, lethargy, absent neonatal reflexes, shock,

Silverman score (4 to 6), FiO2>40%, pH<7.2, base excess >-10,

positive blood culture, C-reactive protein (CRP) positive, mean

alveolar arterial oxygen gradient (AaDO2) >250 mm Hg, mean

arterial alveolar tension ratio (a/A ratio) <0.25 and positive

ventilatory support. The authors found only AaDO2 gradient >250

mmHg as a significant predictor of mortality due to pneumonia

with respiratory distress in neonates (OR 71.1; 95% CI 1.1,

4395).

Publication bias could not be assessed as

there were fewer than 10 studies.

Web Table II depicts

quality assessment of studies using the QATSO Tool [14]. Four of

the five items on the scale were used to assess (i)

External validity, (ii) Reporting, (iii) Bias and

(iv) Confounding. However, no scoring was done. For

studies on risk factors, the measurement of pneumonia was only

found to be objective in one study [15] i.e., clinical records

or laboratory tests. Neither study reported any response rate.

Regarding the control of confounding factors when analyzing

associations, only one study partially accounted for this [15],

while the other did not report adequately on the handling of

variables during the analysis [16].

For study on mortality predictors [17] dose

response relationship could not be determined. The odds ratio in

the study was very large with large confidence intervals (71.1;

95% CI 1.1, 4395). No event rates were reported for both the

groups. Discrepancies exist in the numbers of participants

included in the study. The authors mention the presence of two

groups: respiratory distress with pneumonia and respiratory

distress without pneumonia. However, information on

socio-demographic characteristics, clinical and other important

exposure and confounding information for the two groups was

missing.

DISCUSSION

We conducted a series of systematic reviews

to determine the risk factors associated with development of

neonatal pneumonia and its mortality predictors in India.

Literature is widely available on pneumonia in general and on

neonatal sepsis. However there was near absence of data on

neonatal pneumonia particularly with respect to its risk factors

and mortality predictors in India. Only two studies were

included for risk factors and only one study on mortality

predictors of neonatal pneumonia. Meta-analysis for prematurity

and low birth weight was carried out and low birth weight was

found to be significant for the occurrence of neonatal

pneumonia. Only alveolar-arterial oxygen gradient (AaDO2) >250

mm Hg was found as a significant predictor of mortality due to

pneumonia with respiratory distress in neonates in present

review.

To the best of our knowledge this systematic

review is the first in India studying factors associated with

pneumonia and its mortality in neonates. A rigorous effort was

made to search the relevant studies without time restriction in

Indian context by means of conducting search on nine electronic

databases, hand searching, grey literature, by contacting

authors and in consultation with clinical experts to include

every possible study. Screening and data extraction was carried

out independently by two authors and discrepancies were resolved

by mutual discussion and by getting experts opinion.

Considering the limited evidence in this

review, studies on neonatal sepsis were included up to full text

screening to verify the presence or absence of a subgroup for

pneumonia but no clear underlying etiology as risk factor for

neonatal pneumonia was mentioned in these studies. Consequently

we have excluded studies where pneumonia was part of the

condition but further description for neonatal pneumonia was not

given separately.

Another limitation of the review was the lack

of response from authors of studies of neonatal sepsis that did

not explicitly provide data on the pneumonia component of their

sepsis cases. Due to lack of data in the papers, meta-analysis

for all the identified risk factors was not possible. Results

from our study on risk factors pertain only to cases of

ventilator associated pneumonia, which is a subgroup of neonatal

pneumonia, and therefore, the findings could not be extrapolated

to all the cases of neonatal pneumonia.

The major limitation for mortality predictors

of neonatal pneumonia was that we found limited evidence from a

single study that was not sufficient to conclude despite the

comprehensiveness of our search. One of the potential limitation

could be the language as we have restricted the search only to

articles published in English. Nonetheless, we might have not

missed any relevant studies on neonatal pneumonia as scientific

literature in India is mostly published in English.

Both the studies [15,16] in our review

investigated ventilator-associated pneumonia in neonates that

required mechanical ventilation for 48 hour or more as observed

in other studies [19-23]. In our review the incidence of

ventilator associated pneumonia ranged from 22 to 68 cases per

1000 MV days where as in another study from China it was 27.33

per 1,000 ventilator-days [21]. In contrast, in a study from

USA, VAP rates were as low as 6.5 and 4 per 1000 ventilator days

for patients with EGA <28 week and EGA >28 week, respectively

[22]. Both the included studies [15,16] found Klebsiella

species as the most predominantly isolated organism from the

endotracheal aspirate of neonates with VAP. Similarly in studies

from Egypt [23] and Western India [24], K. pneumoniae was

also found to be the most common organism.

High AaDO2 was found as a significant

predictor of mortality due to pneumonia. Similarly, in a study

from Bangladesh, high AaDO2 was one of the factors significantly

associated with change in antibiotics due to the worsening

condition of the neonates diagnosed with pneumonia [25].

However, they did not specify the limit to describe AaDO2 as

high whereas AaDO2 > 250 mm Hg was considered as high in the

included study [17]. In a multivariate logistic regression, VAP

was the single most important factor found to be significantly

associated with mortality, whereas marginally significant

association was found with presence of an arterial catheter

[22].

In contrast to our meta-analysis findings and

few other studies [19,20,22,26-28], there is one study [29]

where the occurrence of VAP was not associated with low

birth-weight (<1500 g). Results from meta-analysis of two

studies [15,16] found birth-weight of <1500 g as a significant

risk factor to develop VAP (OR 5.61; 95% CI 1.76, 17.90) Our

meta-analysis findings are comparable to a study from China

where low birth weight and premature infants had more chances of

developing VAP [28].

Differences in birth weight were observed

amongst different studies when it comes to defining weight at

birth as low. One study in our review [15] defined VLBW as less

than 1500 g. The other study [16] defined it as in between 1000

to 1500 g and excluded extremely low birth weight babies less

than 1000g weight. However, a study from Thailand reported a

neonatal birth weight less than 750g as an independent risk

factor for VAP [19] and another study established that VAP rates

were high among extremely preterm neonates but birth weight was

specified as £2000g

[22]. A retrospective observational study conducted in Taiwan

found that higher gestational age and weight at birth were

significantly associated in bringing down the VAP occurrence

[20].

Like other studies [27-29], duration of NICU

stay and MV were found as the risk factors but due to lack of

data, meta-analysis for these factors was not possible for our

review. Some intervention studies focused on the association of

the infection control program and VAP prevention [21, 23, 30]

and NICU stay [23]. However, one possible explanation for this

association could be the usage of humidifiers and closed-circuit

ventilation in NICU which provide a major source for growth of

microorganisms [28, 31]. Hence, NICU environment itself can be a

determining risk factor for development of VAP.

Risk factors that other studies have

attributed to neonatal pneumonia of early onset but were absent

from our review were antacid therapy [29], abnormal gastric

aspirate, and low APGAR score among high-risk infants [32].

However, it has also been reported that often risk factors are

absent in pneumonia of early onset, and that sudden onset of

preterm labor by its very nature; is considered as an important

risk factor [33].

Pneumonia is one of the leading causes of

death among neonates in India. Thus, factors that affect

neonatal mortality due to pneumonia and its occurrence are of

great importance for any effort to improve child survival.

However our review concludes that data and primary studies

itself is negligible to substantiate a holistic view on factors

associated with incidences and mortality of neonatal pneumonia.

There is no conclusive evidence on risk factors of neonatal

pneumonia other than ventilator associated pneumonia and hence

it is recognized with this review that neonatal pneumonia, which

comprises the majority of the burden of neonatal sepsis,

continues to be an understudied issue in the Indian neonatal

health scenario. To conclude, we can say that there is an

emergent need to prioritize research toward generating

evidence on neonatal pneumonia and determining factors for its

development and mortality.

Acknowledgments: The authors would like

to extend the gratitude to following persons for their guidance

and support throughout the development process of this

manuscript: Dr Manoj Das, Director Projects, The INCLEN Trust

International, New Delhi; Dr Anju Sinha, Deputy Director

General, Scientist ‘E’, Division of Child Health, Indian Council

of Medical Research, New Delhi; Dr KK Diwakar, Professor and

Head, Department of Neonatology, Associate Dean, Malankara

Orthodox Syrian Church Medical College, Kerala; Mrs Ratheebhai

V, Senior Librarian and Information Scientist, at Manipal School

of Communication, Manipal Academy of Higher Education (MAHE),

Manipal; Dr Ravinder M Pandey, Professor and Head, Department of

Biostatistics, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New

Delhi; Dr B Shantharam Baliga, Professor, Department of

Paediatrics, Kasturba Medical College, Mangalore, Karnataka; Dr

Shrinivas Darak, Senior researcher, PRAYAS, Pune, Maharashtra;

Dr Unnikrishnan B, Associate Dean and Professor, Department of

Community Medicine, Kasturba Medical College, Mangalore. The

authors would like to thank Dr. Ravishankar N, Assistant

Professor, Department of Data Science, Prasanna School of Public

Health (PSPH), MAHE, Manipal for conducting meta-analysis.

Ethics clearance: Institutional

Ethics Committee, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal;

February 16, 2015.

Contributors: NSN: principal

investigator for the project and guarantor for this article. He

conceptualized the research idea and provided overall technical

guidance; LESL: co-investigator for the project. conceptualized

the research idea and provided overall technical guidance. In

addition, LL helped in developing search terms; VSD: drafted the

manuscript and contributed in drafting the full study report to

the funder; SM: conducted the search, piloted the study

selection process, drafted and piloted the data extraction form,

selected studies, extracted data, performed risk of bias,

synthesized data, and drafted the full study report to the

funder; MAG: conducted the search, piloted the study selection

process, drafted and piloted the data extraction form, selected

studies, extracted data, performed risk of bias, synthesized

data, and drafted the full study report to the funder; TL:

conducted the search, piloted the study selection process,

selected studies, conducted hand searching, extracted data,

performed risk of bias, synthesized data, and drafted the full

study report to the funder; BTV: administrative

coordinator for the project, and conceptualized

the research idea. She has also provided technical guidance

throughout the project, during protocol development, finalizing

the full report and addressing the project expert comments. All

authors approved the final version of manuscript, and are

accountable for all aspects related to the study.

Funding: This work was supported

by Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation through The INCLEN Trust

International (Grant number: OPP1084307). The funding source had

no contribution in study design, implementation, collection and

interpretation of data and report writing. Competing

interests: None stated.

REFERENCES

1. Child Mortality Estimates: Global and

regional child deaths by cause. Accessed April 04, 2019.

Available from: http://data. unicef.org

2. Duke T. Neonatal pneumonia in

developing countries. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed.

2005; 90:F211–FF219.

3. Ghimire M, Bhattacharya S, Narain J.

Pneumonia in South-East Asia Region: Public health

perspective. Indian J Med Res. 2012; 135:459.

4. Choudhury AM, Nargis S, Mollah AH, et

al. Determination of risk factors of neonatal pneumonia.

Mymensingh Med J. 2010;19:323-9.

5. Yang L, Zhang Y, Yu X, Luo M.

Prevalence and risk factors of neonatal pneumonia in China:

A longitudinal clinical study. Biomed Res. 2018; 29:57-60.

6. Almirall J, Serra-Prat M, Bolíbar I,

et al. Risk factors for community-acquired pneumonia in

adults: A systematic review of observational studies.

Respiration 2017; 94:299-311.

7. Liu B, Li SQ, Zhang SM, et al. Risk

factors of ventilator-associated pneumonia in pediatric

intensive care unit: A sys-tematic review and meta-analysis.

J Thorac Dis. 2013; 5:525-31.

8. Nair NS, Lewis LE, Godinho M, et al.

Risk factors for neonatal pneumonia in India: A systematic

review and meta-analysis. PROSPERO 2016 CRD42016044019.

Available from:https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD

42016044019

9. Nair NS, Lewis LE, Lakiang T, et al.

Risk factors for mortality due to neonatal pneumonia in

India: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PROSPERO 2016

CRD 42016045398. Available from:https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?

ID=CRD42016045398

10. Nair NS, Lewis LE, Godinho M, et al.

Factors associated with neonatal pneumonia in India:

Protocol for a systematic review and planned meta-analysis.

BMJ Open. 2018; 8: e018790.

11. Nair S, Lewis LE, Lakiang T, et al.

Factors associated with mortality due to neonatal pneumonia

in India: A protocol for systematic review and planned

meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e018790.

12. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et

al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews

and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care

interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med.

2009;151:W65-94.

13. Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et

al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology:

A proposal for reporting. JAMA. 2000; 283:2008-12.

14. Wong WC, Cheung CS, Hart GJ.

Development of a quality assessment tool for systematic

reviews of observational studies (QATSO) of HIV prevalence

in men having sex with men and associated risk behaviours.

Emerg Themes Epidemiol. 2008; 5:23.

15. Tripathi S, Malik GK, Jain A, et al.

Study of ventilator associated pneumonia in neonatal

intensive care unit: Characteristics, risk factors and

outcome. Internet J Med Update. 2010; 5:12-19.

16. Mir ZH, Ali I, Qureshi OA, et al.

Risk factors, pathogen profile and outcome of ventilator

associated pneumonia in a neonatal intensive care unit. Int

J Contemp Pediatr. 2015; 2:17-20.

17. Mathur NB, Garg K, Kumar S.

Respiratory distress in neonates with special reference to

pneumonia. Indian Pediatr. 2002; 39:529-37.

18. Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Higgins JP,

et al. Presenting results and ‘Summary of findings’ tables.

In: Higgins J, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook

for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 5.1.0. The

Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from:

www.cochranehandbook.org

19. Thatrimontrichai A, Rujeerapaiboon N,

Janjindamai W, et al. Outcomes and risk factors of

ventilator-associated pneumonia in neonates. World J Pediatr.

2017; 13:328-34.

20. Lee PL, Lee WT, Chen HL.

Ventilator-Associated Pneu-monia in Low Birth Weight

Neonates at a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: A Retrospective

Observational Study. Pediatr Neonatol. 2017; 58:16-21.

21. Zhou Q, Lee SK, Jiang SY, et al.

Efficacy of an infection control program in reducing

ventilator-associated pneumonia in a Chinese neonatal

intensive care unit. Am J Infect Control. 2013; 41:1059-64.

22. Apisarnthanarak A, Holzmann-Pazgal G,

Hamvas A, et al. Ventilator-associated pneumonia in

extremely preterm neonates in a neonatal intensive care

unit: Characteristics, risk factors, and outcomes.

Pediatrics. 2003; 112:1283-9.

23. Azab SF, Sherbiny HS, Saleh SH, et

al. Reducing ventilator-associated pneumonia in neonatal

intensive care unit using "VAP prevention Bundle": A cohort

study. BMC Infect Dis. 2015; 15:314.

24. Amin AJ, Malam PP, Asari PD, et al.

Sensitivity and resistance pattern of antimicrobial agents

used in cases of neonatal sepsis at a tertiary care center

in western India. Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2016; 7:3060-67.

25. Islam MM, Hossain MM, Al Mamun MA, et

al. Risk factors which affects the change of antibiotics in

neonatal pneumonia observed in a tertiary care hospital.

Northern Int Med Coll. 2014; 6:21-4.

26. Medeiros FD, Alves VH, Valete CO, et

al. Invasive care procedures and neonatal sepsis in newborns

with very low birth weights: A retrospective descriptive

study. Online Braz. J Nurs. 2016; 15:704-12.

27. Afify M, AI-Zahrani S, Nouh MA. Risk

Factors for the Development of Ventilator – Associated

Pneumonia in Critically-ill Neonates. Life Sci J. 2012;

9:302-7.

28. Tan B, Zhang F, Zhang X, et al. Risk

factors for ventilator-associated pneumonia in the neonatal

intensive care unit: a meta-analysis of observational

studies. Eur J Pediatr. 2014; 173:427-34.

29. Afjeh SA, Sabzehei MK, Karimi A, et

al. Surveillance of ventilator-associated pneumonia in a

neonatal intensive care unit: Characteristics, risk factors,

and outcome. Arch Iran Med. 2012; 15:567-71.

30. Ryan RM, Wilding GE, Wynn RJ, et al.

Effect of enhanced ultraviolet germicidal irradiation in the

heating ventilation and air conditioning system on

ventilator-associated pneu-monia in a neonatal intensive

care unit. J Perinatol. 2011; 31:607-14.

31. Garland JS. Strategies to prevent

ventilator-associated pneumonia in neonates. Clin Perinatol.

2010; 37:629-43.

32. Mahendra I, Retayasa IW, Kardana IM.

Risk of early onset pneumonia in neonates with abnormal

gastric aspirate. Pedia-trica Indonesiana. 2008;48:110-13.

33. Webber S, Wikinson AR, Lindsell D, et al. Neonatal

pneu-monia. Arch Dis Child. 1990; 65:207-11.

|

|

|

|

|