|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2021;58:1040-1045 |

|

Predictors of Mortality

in Neonatal Pneumonia: An INCLEN Childhood Pneumonia Study

|

|

C Suresh Kumar, 1 Sreeram

Subramanian,2 Srinivas

Murki,3 JV Rao,4

Meera Bai,5 Sarguna

Penagaram,5 Himabindu Singh,6

Nirupama Padmaja Bondili,7

Alimelu Madireddy,6 Swapna

Lingaldinna,6 Srikanth Bhat,4

Bharadwaj Namala6

From Departments of Pediatrics, 1Institute of Child Health, Niloufer

Hospital, Osmania Medical College, and 4Gandhi Hospital and Medical

College; Departments of Neonatology, 2Paramitha and NeoBBC Children

Hospital, 3Fernandez Hospital, and 6Niloufer Hospital and Osmania

Medical College; and Departments of Microbiology, 5Osmania Medical

College and SRRIT&CD, and 7Fernandez Hospital, Hyderabad, Telangana.

Correspondence to: Dr Sreeram Subramanian, Neonatologist, Paramitha

and NeoBBC Children Hospital,

Hyderabad, Telangana.

Email: [email protected]

Received: June 08, 2020;

Initial review: August 25, 2020;

Accepted: February 10, 2021.

|

Background:

Neonatal pneumonia contributes significantly to mortality due to

pneumonia in the under-five age group, but the predictors of mortality

are largely unknown.

Objective: To evaluate the clinical and

microbiological charac-teristics and other risk factors that predict

mortality in neonates admitted with pneumonia in tertiary care centres.

Study design: Prospective observational cohort

study.

Participants: Term and preterm (32 weeks to 36

6/7 weeks) neonates (<28 days of life) admitted with clinical and

radiological features suggestive of pneumonia.

Intervention: Baseline sociodemographic data,

clinical details, blood culture and nasopharyngeal swabs for virologic

assay (RT PCR for RSV, Influenza) were collected at admission and the

neonates were observed throughout their hospital stay.

Outcome: The primary outcome was predictors of

mortality in neonatal pneumonia.

Results: Five hundred neonates were enrolled in

the study. Out of 476 neonates with known outcomes, 39 (8.2%) died. On

multivariate analysis, blood culture positive sepsis was independently

associated with mortality (adjusted OR 2.51, 95% CI1.23 to 5.11; P-0.01).

Conclusion: Neonates with blood culture positive

pneumonia positive are at a higher risk of death.

Key words: Burden, Early onset sepsis, Outcome, Risk Factors.

|

|

W

ith a mortality rate

of 37/1000 live births,

India ranks among the top five nations

with high under five mortality rates.

Neonatal mortality, comprising 60% of under-five mortality, is

markedly higher than that in any high-income group country [1].

Neonatal sepsis, the third most common cause of neonatal deaths,

has a significant impact on long term neurodevelopment. Neonatal

pneumonia alone accounts for 2% (0.136 million) of under-five

mortality in children in the world [2].

Though the incidence of neonatal sepsis among

NICU admissions in our country is reported to be 14.3%, the

occurrence of neonatal pneumonia and the factors predicting

mortality are not well studied [3-7]. Ventilator associated

pneumonia is common among preterm, low birth weight or

mechanically ventilated newborns [7]. In this study, we evaluate

the clinical and microbiological characteristics and other risk

factors that predict mortality in term and preterm (32 to 36

6/7 weeks) neonates

admitted with pneumonia, in tertiary care public sector

pediatric hospitals, catering predominantly to outborn neonates.

METHODS

This multi-centre, prospective, cohort study,

conducted in two tertiary level public sector hospitals,

included neonates having tachypnea, respiratory distress (chest

retractions/grunting) and evidence of pneumonia on chest X-ray

[8]. Neonates having meconium aspiration syndrome, or

respiratory distress developing within first 2 hours of life and

improving within 12 hours of life or those with major congenital

malformations or those admitted for >24 hours in another

hospital or received antibiotics prior to admission, were

excluded. Nodular or coarse, patchy non-homogenous infiltrates,

air broncho-gram, lobar, multi lobar or segmental consolidation

were considered as radiological evidence of pneumonia. Eligible

infants were enrolled after obtaining consent from either

parent. Blood culture and nasopharyngeal aspirates was taken at

admission and case details, clinical course and the outcome data

were recorded in a predesigned proforma. The clinical staff were

trained to interpret X-rays and the diagnosis was made by

the resident involved in study, was confirmed by a consultant,

and the neonates were managed as per standard treatment

guidelines [9]. Echocardiography was done only when clinically

indicated.

The primary outcome was predictors of

mortality in neonatal pneumonia. Predictors evaluated included

socio-demographic factors, maternal age, maternal fever, parity,

mode of delivery, the clinical features at admission [10] and

during the course of hospitalization as well as microbiological

characteristics of the isolates. The secondary outcomes included

overall blood culture positivity rate in neonatal pneumonia, the

distribution of microbiological causes, the need for higher

respiratory support and complications of pneumonia.

To ensure quality, the microbiological

samples were processed at a NABL accredited laboratory with an

active external quality assessment program. Apart from this, the

unusual bacterial organisms and fungal isolates were confirmed

using MALDI TOF assay at an another NABL accredited laboratory.

Further, interlab comparison of 10% of all positive and negative

viral isolates were done. All data collected were cross-verified

by the site investigators periodically.

Assuming a 10% prevalence of any of the

predictors, an odds ratio of 2.5 for mortality and a mortality

rate of 8% in neonatal pneumonia [11], the number of babies

expected to die due to pneumonia was 121. To realize this

target, 1500 neonates needed to be enrolled. In view of the slow

recruitment and time constraints, an interim analysis was done

on the data until June 2019 (353 neonates were enrolled till

then) and using the proposed predictors, the sample size was

revised to 606. Nasopharyngeal swabs were also collected form

100 healthy term neonates to look at the pattern of asymptomatic

viral colonisation.

The study was approved by the individual

ethics committees of the participating hospitals.

Statistical analysis: Comparison of

categorical variables was done by Chi square test, while

continuous variables were compared using Student t-test.

Risk ratio along with 95% CI was presented. Univariate and

multivariate binary logistic regression analysis was performed

to test the association between possible risk factors and

outcome variables. Variables with statistical significance (P

value <0.1) in univariate analysis were used to compute

multivariate regression analysis. Adjusted odds ratio with 95%

CI was calculated, taking P value < 0.05 as statistically

significant. All statistical analysis was done on IBM SPSS

version 22.

RESULTS

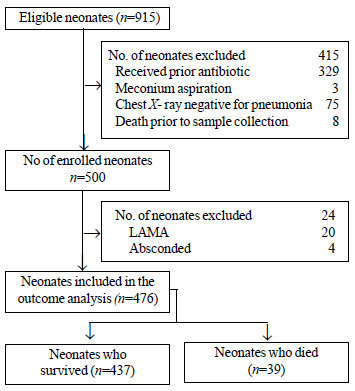

Out of a total of 915 eligible neonates, 500

were enrolled (Fig. 1). The mean (SD) birthweight of the

neonates was 2635.16 (533) g with 8 (1.6%) being very low

birthweight (VLBW). The mean (SD) gestational age was 37.29

(1.9) weeks, with 130 (25%) being preterm. Most of the families

(52%) belonged to upper lower socioeconomic class followed by

lower middle socioeconomic class (41.7%). Out of 476 neonates

with known outcomes, 39 (8.2%) died. The comparison of

parameters between surviving and non-surviving neonates is shown

in Table I. There were significantly higher proportions

of VLBW and preterm neonates in the non-surviving group,

compared to survivors.

|

|

Fig. 1 Study flow chart.

|

Table I Comparison of Sociodemographic, Antenatal and Birth Parameters Between Surviving and Non-Surviving Neonates

| Parameters |

Non-survivors (n=39) |

Survivors (n=437) |

Relative risk (95%CI) |

|

Birthweight (g)a,e

|

2403 (622) |

2639 (515) |

235.6 (63.4 , 407.8 )c |

|

Birthweight ³1500 ge

|

3 (7.7) |

5 (1.1) |

6.29 (1.88, 21.07) |

| Gestational age (wk)a |

36.72 ( 2.69) |

37.29 (1.93) |

0.88 (0.77, 1.01) |

| Preterm birth |

16 (41.0) |

111 (25.4) |

1.91 (1.04, 3.50) |

| Male gender |

32 (82.0) |

331 (75.7) |

1.42 (0.65, 3.14) |

| Vaginal delivery |

21 (53.8) |

218 (49.9) |

1.14 (0.61, 2.14) |

| Primigravida mother |

38 (97.4) |

382 (87.4) |

4.99 (0.69, 36.32) |

|

Antenatal visitsb |

4 (3,4) |

3 (3,4) |

0.95 (0.76, 1.19) |

|

Maternal feverd |

1 (2.6) |

11 (2.5) |

1.07 (0.15, 7.79) |

| Apgar score (1 min)b |

5 (5,5) |

5 (5,5) |

0.81 (0.54, 1.19) |

| Apgar score (5 min)f |

8 (8,8) |

8 (8,8) |

0.65 (0.47, 0.89) |

|

Weight at admission (g)a,e

|

2382.44 (628.47) |

2691.68 ( 569.66) |

309.12 (120.6, 497.6)c |

|

Age at admission (h)a,e |

136.46 ( 173.07) |

301.67 (232.74) |

165.2 (90.03, 240.3)c |

|

Hospital stay a,g |

5.9 (6.8) |

7.81 ( 5.6) |

1.9 (-0.02, 3.84) |

|

Values in n (%),amean (SD) or bmedian (IQR). cmean

difference (95% CI). dmaternal fever within 1 week prior

to delivery. eP<0.001, fP=0.007, gP=0.05. |

Onset of symptoms occurred at a mean of 5.6

days of life in the neonates who died, compared to 12.5 days in

those who survived [mean difference 6.9 (95% CI 3.7, 10); P<0.001].

The most common presenting symptom was difficulty in feeding

seen in 219 (46%)] neonates, followed by fever, noted

in 110 (23%) of the neonates. The most common sign was

tachypnea, mean (SD) respiratory rate being 63.7 (6.8) breaths

per minute and the median Silverman Anderson score at admission

was 4 (IQR 3,6). At admission, 302 (60%) neonates required

oxygen, with 143 (28%) being started on CPAP, and 55 (11%)

requiring intubation. The comparison of clinical features and

course between surviving and non-surviving neonates is shown in

Table II

Table II Comparison of Clinical Features and Course of Illness Between Surviving and

Non-Surviving Neonates and Survivors

| Parameters |

Non-survivors (n=39) |

Survivors (n=437) |

Relative risk (95%CI) |

| Cough |

2 (5.13) |

65 (14.87) |

0.34 (0.08, 1.40) |

| Running nose (cold) |

1 (2.56) |

38 (8.7) |

0.29 (0.04, 2.15) |

| Fever |

7 (17.95) |

103 (23.57) |

0.73 (0.32, 1.66) |

| Breathing difficulty |

33 (84.62) |

398 (91.08) |

0.58 (0.25, 1.39) |

| Apneab |

5 (12.82) |

14 (3.2) |

3.35 (1.31, 8.57) |

| Cold to

touchc |

7 (17.95) |

26 (5.95) |

2.99 (1.32, 6.79) |

| Vomiting |

4 (10.26) |

32 (7.32) |

1.43 (0.51, 4.02) |

| Diarrhea |

0 |

6 (1.37) |

- |

| Feeding difficulty |

22 (56.41) |

197 (45.08) |

1.53 (0.81, 2.88) |

| Seizuresb |

8 (20.5) |

33 (7.6) |

2.74(1.26, 5.97) |

| Movement

only with stimulationb |

10 (25.64) |

46 (10.53) |

2.58 (1.26, 5.29) |

| Heart rate >180/min |

4 (10.26) |

46 (10.53) |

0.96 (0.34, 2.71) |

| SAS

scorea,b |

5 (4, 6) |

4 (3,5) |

1.278 (1.054, 1.550) |

| Grunting |

26 (66.67) |

226 (51.72) |

1.77 (0.91 to 3.45) |

| CFT>3 seconds |

5 (12.82) |

48 (10.98) |

1.19 (0.47, 3.04) |

| Temp >37.5 ºC |

4 (10.2) |

101 (23) |

0.40 (0.16, 1.03) |

| Temp <36.5 ºC |

4 (10.26) |

17 (3.89) |

2.48 (0.88, 6.99) |

| Cyanosisc |

8 (20.51) |

16 (3.66) |

4.71 (2.16, 10.24) |

| SpO2< 90% |

23 (59) |

205 (46.9) |

1.56 (0.84, 2.88) |

| Bulging

anterior fontanelle |

2 (5.13) |

23 (5.26) |

0.91 (0.22, 3.78) |

| Lethargy |

18 (46.15) |

150 (34.32) |

1.56 (0.83, 2.94) |

| Abdominal

distensionb |

6 (15.38) |

22 (5.03) |

2.95 (1.24, 7.05) |

| Hepatomegaly |

4 (10.26) |

51 (11.67) |

1.19 (0.47, 3.04) |

| More than one skin pustule |

1 (2.56) |

1 (0.23) |

6.55 (0.90, 47.73) |

| Respiratory support at admission |

|

|

|

| Oxygend |

14 (35.9) |

272 (62.24) |

0.37 (0.19, 0.69) |

| Intubationc |

16 (41.03) |

38 (8.7) |

6.28(3.06, 12.86) |

| CPAP |

9 (23.08) |

127 (29.06) |

1.36(0.6, 3.14) |

|

Values in (%) or amedian (IQR). bP=0.01; cP<0.001;

P=0.002. CPAP: continous positive airway pressure; SAS:

Silverman Anderson score. |

While blood culture positivity rate was

significantly higher among neonates who died, viral isolates in

the nasopharynx was significantly higher among survivors, RSV B

being the most common. (Table III). Overall blood culture

positivity rate was 19.2%, Gram negative organisms were isolated

in 45 (47%) and Gram-positive organisms in 23 (24%) neonates.

Klebsiella was the commonest organism isolated and was seen in

22 neonates (23%). While 27 (28%) neonates showed fungal growth

with Candida species,190 (38%) neonates were positive for

viral PCR. Among 100 healthy term neonates, 7 were found to have

asymptomatic viral colonisation (Influenza B – 5, H1N1 – 1, both

influenza A and B -1)

Table III Comparison of Microbiological Parameters Between Surviving and Non-Surviving Neonates

| Parameters |

Non-survivors (n=39) |

Survivors (n=437) |

Relative risk (95%CI) |

P value |

| Blood culture positive |

15 (38.4) |

78 (17.8) |

2.63 (1.38 - 5.01) |

0.003 |

| Gram positive |

2 (5.1) |

20 (4.5) |

0.52 (0.12 - 2.25) |

0.38 |

| Gram negative |

8(20.5) |

38 (8.7) |

0.49 (0.06 - 3.71) |

0.49 |

| Fungal |

5(12.8) |

20 (4.5) |

1.46 (0.41 - 5.12) |

0.56 |

| Viral PCR positive |

4 (10.3) |

177 (40.5) |

0.18 (0.06 - 0.525) |

0.001 |

| RSV B |

3 (7.7) |

118 (27) |

0.24 (0.07 - 0.79) |

0.01 |

|

Values in n (%). RS: respiratory syncytial virus. |

On multivariate analysis, positive blood

culture (adjusted OR 2.51, 95% CI 1.23 to 5.11; P=0.01)

emerged as the independent predictor of mortality in neonates

with pneumonia.

DISCUSSION

In this study the mortality rate due to

neonatal pneumonia was found to be 8.2%. The blood culture

positivity was an independent predictor of mortality, though the

type of organism did not affect mortality. The mortality rate is

less than that reported (12%) in the multicenter national

neonatal perinatal database report [11]. In the DeNIS cohort [3]

though the overall blood culture positivity among neonates with

pneumonia was almost similar to our study (15% vs 19%,

respectively), the mortality rate was lower (45% vs 16%,

respectively) and was probably due to differences in inclusion

criteria and the higher prevalence of multidrug resistant

organisms. In the present study, 50% of the bacterial isolates

were Gram negative, Klebsiella being the commonest

organism reflecting community prevalence. On the other hand,

two-third of the culture positive isolates were Gram negative in

DeNIS study, Acinetobacter being the commonest isolate

[3]. Streptococcus pneumoniae, increasingly found in

possible serious bacterial infections (pSBI) among young

infants, has been reported to contribute to mortality [12].

However, we did not isolate any S. pnemoniae, possibly

due to inherent difficulty in isolating in blood cultures and

the need for additional techniques. The overall microbiological

yield was 53%, which is double than that reported in

community-acquired serious bacterial infections [12].

The incidence of community-acquired fungal

pneumonia in our cohort, confirmed by molecular diagnosis (MALDI

TOF), was very high (25% of culture positive), compared to other

studies [3,12], although this did not translate into higher

mortality. This is intriguing as none of the neonates received

any antibiotic nor were admitted in any hospital prior to

enrolment.

The viral positivity rate in our study (38%)

was similar to that of a community-based surveillance study

(42%) involving infants with respiratory illness from

Bangladesh, but neonatal pneumonia constituted only 11% in their

cohort [13]. Several hospital based studies in neonates, from

Asia, have reported 30% incidence of viral lower respiratory

tract infections, especially due to RSV [14]. The in-hospital

case fatality rate of viral pneumonia was 0.2% which is

significantly lower than the reported incidence in LMIC

countries [5·3% (95% CI 2·8 to 9·8)] possibly due to better

management in tertiary care centers [15]. Moreover, neonates

with viral pneumonia had higher body weight and presented at a

later age in the neonatal period, which could possibly explain

better outcome., The most common viral isolate in the present

study was RSV, consistent with the global burden, but unlike the

usual pattern, type B strain was dominant, which could be

another reason for better survival [14-16].

The symptoms and signs used in our study were

similar to those in integrated management of neonatal and

childhood illness (IMNCI) and young infant study [17,18]. Though

they have been shown to predict the occurrence of pBSI, our data

failed to show their association with mortality.

The strength of our study was the use of a

very strict case definition, which, to the best of our

knowledge, is the first and largest of its kind. The limitation

of the study was the inability to enroll the originally planned

1500 neo-nates, due to logistic constraints. Other etiological

agents like Mycoplasma, Chlamydia, and Pneumococcus requiring

special techniques for isolation, were not evaluated. The

investigators involved in the inter-pretation of X-rays

were not blinded to clinical features.

In conclusion we found blood culture

positivity in neonatal pneumonia as an independent predictor of

mortality. The role of fungus in community acquired neonatal

pneumonia needs further exploration and there is need to be

vigilant and consider early antifungal therapy especially in

those who do not seem to respond. The high incidence of viral

pneumonias in our study emphasizes the need to consider

nasopharyngeal swab in the neonatal pneumonia work up.

Vaccination against RSV immediately after birth may be a

potential strategy to lower the burden of neonatal pneumonia.

[19]

Acknowledgements: Technical advisory

group constituting Prof Dr Lalitha Krishnan, Prof Dr Siddharth

Ramji and Prof Dr Ramesh Agarwal for their critical appraisal of

the project and for providing technical guidance. INCLEN,

especially Dr Manoj K Das, for providing continuous technical

and logistic support for the study. Dr Murali Reddy and his team

from Beyond P value for providing statistical assistance. We

also thank the project coordinator Mrs. Pavani Soujanya for

supervising and coordinating the project, and also analyzing the

viral isolates.

Ethics clearance: (i)

Ethics committee of Osmania medical college, Hyderabad; Reg No

ECR/300/Inst/AP/2013 Date of approval June 23, 2015; (ii)

Ethics committee of Gandhi Medical college, Hyderabad,

ECR/180/Inst/AP/2013- October 13, 2015; and (iii) Ethics

committee of Fernandez hospital, Hyderabad; ECR/933/Inst/TG/2017

– December 09, 2015.

Contributors: SK, SS, SM, JVR, MB:

involved in the conception, design of the project; SK,SS,SM

were also involved in data analysis, drafting of manuscript; MB,

SP, NPB: designed and conducted the microbiological aspects of

the study; HS, AM, SL, SB, BN: involved in case enrolment and

supervision. All the authors were involved in critical appraisal

and have reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by Bill

and Melinda Gates Foundation through The INCLEN Trust

International (Grant number: OPP1084307). The funding source had

no contribution in study design, implementation, collection and

interpretation of data and report writing. Competing

interests: None stated.

|

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN?

•

Predictors of moratality

in neonatal pneumonia are largely unknown.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS?

•

Blood culture positivity independently predicts

mortality in neonatal pneumonia.

•

High prevalence of RSV B and Candida was seen

in neonatal pneumonia.

|

REFERENCES

1. United Nations Inter-agency Group for

Child Mortality Estimation (2019). Accessed April10,2020.

Available from: https://childmortality.org/data/India

2.. Liu L, Oza S, Hogan D, et al. Global,

regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2000-13,

with projections to inform post-2015 priorities: An updated

systematic analysis. Lancet. 2015;385:430-40.

3. Investigators of the Delhi Neonatal

Infection Study (DeNIS) Collaboration Characterisation and

antimicrobial resistance of sepsis pathogens in neonates

born in tertiary care centres in Delhi, India: A cohort

study. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4: e752-e60.

4. Duke T. Neonatal pneumonia in

developing countries. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed.

2005;90:F211-19.

5. Dutta S, Reddy R, Sheikh S, et al.

Intrapartum antibiotics and risk factors for early onset

sepsis. Archi Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2010 Mar

1;95:F99-103.

6. Chacko B, Sohi I. Early onset neonatal

sepsis. Indian J Pediatr. 2005;72:23-26.

7. Hooven TA, Polin RA. Pneumonia. Sem

Fetal and Neonatal Med. 2017:22:206-13.

8. Mathur NB, Garg K, Kumar S.

Respiratory distress in neonates with special reference to

pneumonia. Indian Pediatr. 2002;39:529-37.

9. Workbook On CPAP. Science evidence and

practise. Deorari AK, Kumar P, Murki S editors. 4th edition.

Accessed April 01, 2020. Available from:

https://www.newbornwhocc.org/CPAP-book-2017.html

10. Goldstein B, Giroir B, Randolph A;

Inter-national Pediatric Sepsis Consensus Conference:

Definitions for Sepsis and Organ Dysfunction in Pediatrics.

Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6:2-8.

11. Report of National Neonatal Perinatal

Database (NNPD) 2002-2003. Accessed January 20, 2014.

Available from: http://www.newbornwhocc.org/nnpo.html

12. Saha SK, Schrag SJ, El Arifeen S, et

al. Causes and incidence of community-acquired serious

infections among young children in south Asia (ANISA): an

observational cohort study. Lancet. 2018;392:145-59

13. Farzin A, Saha SK, Baqui AH, et al.

Population-based incidence and etiology of

community-acquired neonatal viral infections in Bangladesh.

Pediatric Infect Dis J. 2015;34: 706-11.

14. Zhang Y, Yuan L, Zhang Y, et al.

Burden of respiratory syncytial virus infections in China:

Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health.

2015;5:020417.

15. Shi T, McAllister DA, O’Brien KL, et

al. Global, regional and national disease burden estimates

of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory

syncytial virus in young children in 2015: A systematic

review and modelling study. Lancet. 2017;390:946-58.

16. Rodriguez-Fernandez R, Tapia LI, Yang

C-F, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus genotypes, host

immune pro-files, and disease severity in young children

hospitalized with bronchiolitis. J Infect Dis.

2018;217:24-34.

17. Ingle G K, Malhotra C. Integrated

management of neonatal and childhood illness: An overview.

Indian J Comm Med. 2007;32:108-10.

18. The Young Infants Clinical Signs

Study Group. Clinical signs that predict severe illness in

children under age 2 months: a multicentre study. Lancet.

2008;371:135-42.

19. Giersing BK, Modjarrad K, Kaslow DC, et al. Report from

the World Health Organization’s Product Development for Vaccines

Advisory Committee (PDVAC) meeting, Geneva, 7-9th Sep 2015.

Vaccine. 2016;34:2865-69.

|

|

|

|

|