|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2019;56: 972 -974 |

|

Life-threatening Hypercalcemia as the First Manifestation of

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

|

|

Kakali Roy1,

Rajni Sharma1*,

Manisha Jana2

and Vandana Jain1

From Departments of 1Pediatrics

and 2Radiology, AIIMS, New Delhi, India.

Email:

[email protected]

|

|

Hypercalcemia of malignancy, usually

reported in adults in advanced stages, is rare in children. A 4-year-old

boy presented with intermittent episodes of severe hypercalcemia, which

improved with intravenous hydration therapy, furosemide and

bisphosphonates as the initial manifestation of occult acute

lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatricians should rule out hematological

malignancy in patients with severe hypercalcemia.

Keywords: Constipation, Diabetes insipidus.

|

|

S

evere hypercalcemia (>14 mg/dL) is rare in

children but can result in coma, arrhythmias and death. In adults, the

most common cause of severe hypercalcemia is malignancy (advanced

stages), which portends a poor prognosis. Hypercalcemia of malignancy

has been rarely reported in children [1]. We present a boy with

life-threatening hypercalcemia who was diagnosed with occult acute

lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

A 4-year-old boy presented with recurrent vomiting,

polyuria, polydipsia, extreme irritability, irrelevant talk,

constipation and right leg immobility with the history of low back pain

for two months. The child was in severe dehydration with altered

sensorium, high blood pressure (>99 th

centile) without any neurological deficit, hepatosplenomegaly or

lymphadenopathy. On laboratory investigations, serum calcium was 19.2

mg/dL (ionized 8.2 mg/dL), phosphate 3.7 mg/dL, albumin 3.7 g/dL,

alkaline phosphatase 389 IU/L, high urinary calcium: creatinine ratio,

25(OH)D 40 nmol/L (normal 50-250), increased 1,25(OH)2D

271 pmol/L (normal 52-117); and normal venous blood gas, renal function

and serum magnesium. He was managed with hydration with double

maintenance fluid and intravenous furosemide. Pamidronate (1 mg/kg) was

administered over 4 hours by intravenous infusion. The serum calcium

improved to 9.2 mg/dL and subsequently fell to 6.8 mg/dL over the next 3

days requiring oral calcium supplementation. A diagnosis of primary

hyperparathyroidism was considered based on serum PTH level of 106 pg/ml

(15-68.3) and doubtful PTH gland adenoma on ultrasound of neck.

Sestamibi scan, 4D CT neck and 4D MRI neck did not identify any

parathyroid gland abnormality. A repeat serum PTH was reported low at

1.3 pg/mL with normal calcitonin (<2 pg/mL, normal 0-18.2). Work up for

PTH-independent causes of hypercalcemia including granulomatous disease

(tuberculosis and angiotensin-converting enzyme levels for sarcoidosis)

was normal.

|

| (a) |

(b) |

|

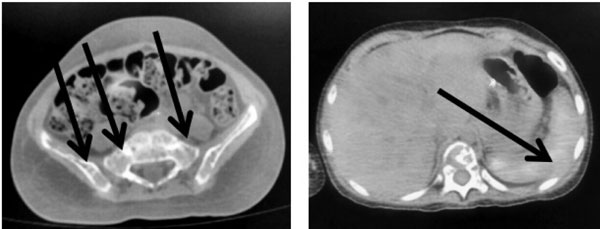

Fig. 1 Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET

scan showing extensive lytic changes in skeleton (a) with

diffusely increased FDG uptake in spleen (b).

|

Radiographs showed extensive generalized bony lytic

lesions of skull (salt and pepper appearance), phalanges and spine with

vertebral collapse. Bone-scan showed metastatic calcification of stomach

and bilateral lung secondary to hypercalcemia. In the background of

extensive bony lytic lesions and suppressed PTH, malignancy-induced

hypercalcemia was considered. Complete blood count, peripheral smear,

lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), uric acid and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) were

normal. Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy were normal. Parathyroid

related peptide (PTHrP) was also normal <0.8 pmol/L (<1.3). CECT

abdomen, chest and neck revealed diffuse geographic lytic lesions with

diffuse osteopenia (brown tumor) but no solid tumor was identified.

Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET scan showed extensive lytic changes

involving the entire visualized skeleton with diffusely increased FDG

uptake in the spleen suggestive of a lymphoproliferative disorder (Fig.

1a, 1b). A repeat bone marrow aspiration and biopsy revealed

inconclusive small round cell tumor. Subsequently, a CT-guided bone

marrow biopsy was done from iliac crest lesions, which showed 54%

malignant cells consistent with round cell tumor. Immuno-histochemistry

was positive for PAX5 (B cell marker), T’dt (precursor of lymphocytes),

MIC-2, and CD20 (focal) markers and negative for CD3 (T cell marker), CD

56, Chromogranin (neuroendocrine marker), which confirmed the diagnosis

of B-cell ALL. He was started on standard-risk induction chemotherapy

for ALL (vincristine, L-asparaginase, prednisolone and intra-thecal

methotrexate) with which remission was achieved.

In summary, our case presented with severe

hypercalcemia, high PTH and parathyroid adenoma on USG neck, pointing

towards a diagnosis of primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT). Occurrence of

bony pains and the characteristic salt and pepper appearance of skull in

our patient were also consistent with PHPT. However, multiple extensive

bony lytic lesions are very rare in PHPT [2]. Serum PTH was found to be

suppressed on repeat testing pointing to the possibility of malignancy

in the absence of other clinical, haematological or biochemical

evidence. Our case report highlights the importance of repeating hormone

assays (PTH) when the clinical picture is inconsistent and the

limitations of a single rephine biopsy in detecting occult lymphoblastic

malignancies.

Hypercalcemia of malignancy is very rare in children

and usually seen in ALL, rhabdomyosarcoma and less often in lymphoma,

hepatoblastoma, and neuroblastoma [3]. Hypercalcemia in solid tumor

presents late in the disease course and is more resistant to treatment,

unlike ALL where it may present early without other clinical

manifestations [4]. There are several mechanisms of malignancy-induced

hypercalcemia, such as PTHrP by malignant solid tumours and osteolytic

metastasis with local release of cytokines including osteoclast

activating factor or unregulated extrarenal production of 1,25(OH)2D

(in lymphoma and granulomatous diseases) [5]. In one study of 22 ALL

patients with hypercalcemia, half had elevated PTHrP thought to be

released from blast cells [6]. In our case, the PTHrP was normal and

hypercalcemia probably resulted from the extensive osteolytic lesions

due to local pro-duction of cytokines and possibly high 1,25(OH)2D

levels.

We conclude that severe hypercalcemia, extensive

generalized bony lytic lesions and suppressed PTH levels may point to an

underlying malignancy even in the absence of occult features which

should be ruled out by appropriate investigations.

Contributors: KR: reviewed the literature and

drafted the manuscript; RS,MJ,VJ: critically reviewed the manuscript.

All authors were involved in management of the case and approved the

final manuscript.

Funding: None; Competing interest: None

stated.

References

1. Reagan P, Pani A, Rosner MH. Approach to diagnosis

and treatment of hypercalcemia in a patient with malignancy. Am J kidney Dis.

2014;63:141-7.

2. De Manicor NA. Primary hyperparathyroidism: a case

study. J Perianesth Nurs. 2004;19:334-41.

3. Fisher MM, Misurac JM, Leiser JD, Walvoord EC.

Extreme hypercalcemia of malignancy in a pediatric patient: therapeutic

consideration. AACE Clinical Case Rep. 2015;1:e12-5.

4. Celil E, Ozdemir GN, Tuysuz G, Tastan Y, Cam H,

Celkan T. A child presenting with hypercalcemia. Turk Pediatri Arsivi.

2014;49:81-3.

5. Davies JH. A Practical Approach to hypercalcemia.

In: Allgrove J, Shaw NJ, editors. Calcium and Bone Disorders in Children

and Adolescents. Endocrine Development. Basel: Karger Publishers; 2009.

p. 93-114.

6. Inukai T, Hirose K, Inaba T, Kurosawa H, Hama

A, Inada H, et al. Hypercalcemia in childhood acute lymphoblastic

leukemia: frequent implication of parathyroid hormone-related peptide

and E2A-HLF from translocation 17;19. Leukemia. 2007; 21:288-96.

|

|

|

|

|