|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2019;56:951-957 |

|

Allergy

Testing – An Overview

|

|

Neeraj Gupta 1,

Poojan Agarwal2,

Anil Sachdev1 and

Dhiren Gupta1

From 1Division of Pediatric

Emergency, Critical Care, Pulmonology and Allergic Disorders, Department

of Pediatrics, Institute of Child Health, and 2Department

of Pathology, Sir Ganga Ram Hospital, Rajinder Nagar, Delhi, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Neeraj Gupta,

Consultant, Division of Pediatric Emergency, Critical Care, Pulmonology

and Allergic Disorders, Department of Pediatrics, Institute of Child

Health, Sir Ganga Ram Hospital, Rajinder Nagar, Delhi 110060, India.

Email: [email protected]

|

|

Childhood allergies pose huge economic burden and adverse effects on

quality of life. Serum IgE has been considered a surrogate allergy

marker for decades. Availability of several over-the-counter allergy

tests add to confusion of partially trained caregivers. The present

review focuses on current status of allergy testing in Indian scenario.

Various in-vitro and in-vivo diagnostic modalities are

available for allergy detection. Skin prick tests are useful for

aero-allergies whereas oral challenge tests are best for identifying

suspected food allergies. An allergy test should be individualized based

on clinical features, diagnostic efficacy, and cost-benefit analysis.

Keywords: Challenge test, Histamine,

Hypersensitivity, IgE, Patch test, Skin prick test.

|

|

A

llergy encompasses a wide spectrum of

manifestations affecting skin, respiratory and gastrointestinal systems.

Several genetic, environmental and socio-economic factors play an

important role in the diverse presentation. A rising trend of allergies

has been noted worldwide affecting physical, social and psychological

well-being and increasing economic burden and disability adjusted life

years [1,2]. It is estimated that about 20-30% of the Indian population

suffers from atleast one form of allergy, of which, rhinitis is most

common followed by asthma [3,4]. Scarce diagnostic facilities and

limited knowledge further add onto the disease burden. This review

focuses on various available modalities for allergy diagnosis and their

clinical relevance.

Terminology

As per World Allergy Organization (WAO) and European

Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology (EAACI), hypersensitivity

is defined as a state when there are objectively reproducible symptoms

or signs initiated by an exposure to a defined stimulus at a dose

tolerated by other persons [5]. Allergy is a chronic clinical condition

involving an abnormal immune reaction to an ordinarily harmless

allergen, commonly mediated by IgE production though other mechanisms

can play significant role [6]. An IgE-mediated allergy with personal or

familial tendency is ‘atopy’. Hyper-sensitivity reactions usually have

an immunological basis but all are not allergies. This understanding is

necessary as most of the available allergy tests can only detect

hypersensitivity in response to a particular object/allergen, which

requires clinical correlation to be labelled as allergy.

Types of Hypersensitivity Reactions

1. Type I (Immediate or IgE-mediated) –

Rapid immunologic reaction in a previously sensitized individual,

triggered by binding of an antigen to IgE antibodies on the surface

of mast cells [7].

2. Type II (Antibody-mediated

cytotoxic/cytolytic) – IgG- and IgM- mediated cellular damage

with complement and phagocyte involvement.

3. Type III (Immune complex mediated) –

Antigen-antibody immune complex deposition causing complement

activation and tissue damage.

4. Type IV (Cell-mediated or delayed

hypersensitivity) – Direct cell damage mediated by various

cytokines released by sensitized Th1 cells.

Most of the clinically relevant allergies are

mediated via type I hypersensitivity. Commonly used in vitro

tests detect free IgE, whereas bound IgE and mast cell degranulation can

be demonstrated by in vivo procedures (skin-prick or challenge

tests). Food allergies have various IgE (e.g., urticaria,

angioedema, asthma, rhinitis, anaphylaxis and oral allergy) and non-IgE

(e.g., dermatitis hereptiformis, Heiner’s syndrome,

procto-enterocolitis, enteropathy and Celiac disease) mediated

mechanisms; hence, IgE-based tests alone are insufficient for their

diagnosis [8]. Atopic dermatitis and eosinophilic disorders may have

both types of mechanisms.

Allergy Diagnosis

The key lies in detailed clinical history, relevant

physical examination and knowledge about local environment. Temporal

relationship of allergen exposure and onset of clinical features,

periodicity of symptoms (seasonal/perennial, diurnal),

aggravating/relieving factors, history of travel, pet or insect

exposure, number of affected body systems, familial atopy and

occupational history should be elicited. Table I enlists

common indoor allergens and associated risk factors. Attending

physician/allergist should be aware of local aeroallergens with seasonal

variation (Web Table I) and regional predominance (Web

Table II). Knowledge about regional pollen calendar combined

with clinical correlation can help in tailoring allergen panel for

individual patient.

TABLE I Common Indoor Allergens

|

Organism |

Allergen |

Location |

Risk factors |

|

Dust Mite |

Der p1 and Der f1 |

Carpet, bedding (mattress/pillow/ |

Humidity, older homes and absence of air- |

|

|

curtains) and upholstery |

conditioning |

|

Dog |

Can f1 and albumin |

Carpet and bedding; airborne |

Depends on the breed and/or animal |

|

Cat |

Fel d1 |

Carpet and bedding; airborne |

Cat allergen is universal |

|

Cockroach |

Bla g1-4 and Per a1 |

Kitchen and dining |

Humidity and open food sources |

|

Fungus |

Various |

Bathrooms and/or kitchens; areas of water damage |

Humidity, water damage, and leaky plumbing |

|

Der p: Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus; Der f:

Dermatophagoides farinae; Can f: Canis familiaris; Fel d: Felis

domesticus; Bla g: Blattella germanica; Per a: Periplaneta

americana.

|

Laboratory Tests

Tests should be carefully selected based on patient

history, environmental triggers and operational issues (cost,

anaphylaxis risk, time required). Tests may be targeted towards either

cause identification or functional and structural disability assessment.

Immunological Tests: For Cause Identification

In vitro tests

(i) Total IgE levels – A reaginic

antibody was discovered by Ishizaka (1966) and Johansson (1967) groups

independently and named as IgE by WHO in 1968 [6]. Serum total IgE

levels, a conglomerate of all specific IgE molecules, are neither

sensitive nor specific for allergy diagnosis [9]. Raised levels may be

documented in conditions like parasitic infestations, immunodeficiency

disorders (e.g., AIDS, hyper IgE syndromes etc.), Ebstein Barr

virus (EBV) infection, rheumatoid arthritis and smoking [10]. IgE

molecules produced against specific individual antigens are labelled as

serum specific IgE (sIgE). These were detected by Radio-Allergo-Sorbent

Test (RAST) using radiolabeled (I 125)

antihuman IgE molecules. Radio-isotopes have now been replaced by enzyme

conjugated antihuman IgE antibodies (Immunocap). The major pitfall of

sIgE estimation is false positivity with high total IgE levels (>300

kIU/L) due to non-specific binding to test allergens [11].

(ii) Component resolved diagnostics (CRD):

Epitopes on some allergens may have structural homology with others.

For example, allergenic epitopes on birch pollen share similar

structural characteristics to peanut and hazel nut (Web Table

III), which may be responsible for oral pruritus while eating fresh

nuts in a birch pollen allergic individual without any true nut allergy

(oral allergy syndrome). During testing with crude allergen extract for

either of them there could be false positive reaction to others due to

phenomenon of cross reactivity. To combat this problem, recombinant

allergens using a specific epitope are being manufactured to improve

diagnostic efficacy of in-vitro food allergen tests [12] and better

management of the patients [13]. The high-risk component allergenic

proteins for peanut (Ara h1, 2, 3, 9), hazelnut (Cor a8, 9, 14), walnut

(Jug r1, 2, 3), soya (Gly m5, 6), wheat (Tri a14, 19) and Rosacea fruits

(Pru p3, Mal d3) can be detected with CRD [13]. It is a promising tool

for improving the specificity in allergy testing though more studies are

required for its validation.

In vivo tests

(i) Skin prick test (SPT) – SPT

is an age-old technique first described by Charles Harrison Blackley

(1860s) in patients of ‘hay fever’. It detects bound IgE by replicating

a mini allergic reaction in the already sensitized host once the

allergens are delivered epicutaneously. SPT is considered "gold

standard" test for diagnosing IgE mediated allergic diseases [14].

SPT should be performed at a place well equipped with

resuscitation facilities. As, blood vessels and pain receptors are

located in deep dermis, SPT is pain-free and associated with minimal

risk of bleeding or infection if performed appropriately (Fig.

1a) [15]. Crude extract may directly be pricked (Prick test)

followed by SPT, in case of non-availability of standard allergen

extract [16]. Selection of antigens should be based upon patient’s

clinical and environmental history, occupation and socio-economic

factors. House dust, house dust mite, relevant pollens (grass, tree or

weeds), fungus (Alternaria, Aspergillus), insects (Cockroach) and pet

animals (dog, cat, buffalo) dander are the commonest aeroallergens

prevalent in India whereas milk, egg, peanut, soya, wheat, tree nut,

fish and shell fish contribute to majority of food allergens [17,18].

Cockroach remains the predominant allergen among insects whereas common

occupational allergens are latex and chemicals. Honey bees are important

allergens in high risk groups like bee keepers. A patient with either

recurrent or persistent symptoms not adequately controlled by preventer

therapy should be tested with SPT. Patients with allergic rhinitis or

asthma having either persistent or moderate to severe symptoms as per

the ARIA and GINA guidelines should be subjected to allergy testing.

Patients on anti-histaminics and immunomodulators, on b-blockers, with

unhealthy skin condition, within 4 weeks of anaphylaxis and extremes of

age are not suitable for SPT. Clinical correlation of test results might

help in instituting specific allergen avoidance measures and targeted

immunotherapy in select cases.

|

|

|

Fig. 1 Skin prick test: (a)

technique; (b) ‘Wheal’ and ‘Flare’ reactions after SPT to

different allergens (1,2,3,4).

|

Histamine and normal saline serve as positive and

negative controls respectively and read after 10 minutes and 15 minutes

[16]. Positive reaction is suggested by appearance of a wheal at the

prick site (Fig. 1b). The maximum diameter of the wheal is

measured and reaction interpreted in millimeters (mm) of wheal diameter

[19, 20]. Also, any pseudopod (an extra protuberance to the regular

circular shape) if observed, is separately mentioned. Positive control

should be at least 3 mm or more than negative control to establish test

validity. Any reaction with normal saline more than 3 mm should be

considered as baseline high reactivity of the skin, making test

conditions invalid. If positive and negative controls are within 3 mm of

each other, the test should be considered invalid. Any allergen showing

a wheal size of ³3

mm than the negative control should be considered positive indicator of

hypersensitivity. Any wheal size more than 8 mm suggests high positive

predictive value.

Factors influencing SPT

• Medications – Certain medications may

affect the results of SPT as mentioned in Table II

[16]. SPT reaction usually declines after 6 months to 3 years of

allergen immunotherapy.

• Age – SPT is currently practiced

beyond 6 months of age though no lower or upper age limit cutoff is

recommended [16]. Skin reactivity declines after 60 years.

• Test area – The mid and upper back are

33% more reactive than the lower back. The back as a whole is more

reactive (53%) than the forearm. An area approximately 5 cm away

from the wrist and 3 cm from the antecubital fossa, on the forearm

is usually used [16]. Left forearm is generally preferred.

• Distance between two pricks – A minimum

of 2 cm gap should be present between two adjacent test sites. This

is to prevent non-specific enhancement through nearby axon reflex

and also to avoid merging of wheals from strong reactions in the

nearby area.

• False positives – Skin conditions

(dermatographism, acute or chronic urticaria, cutaneous

mastocytosis), naturally occurring histamine in some allergen

extracts (insect venom, mold, foods), non-standard allergen

preparations (irritant reaction), cross-reactivity with homologous

proteins.

• False negatives – Recent (within 4

weeks) anaphylaxis, medications (Table II), technical

(low-potency extract, false technique), UV exposure.

TABLE II Drugs to be Stopped Before Skin Prick Test

|

Medication |

Period for withholding before test |

|

Antihistaminics (H1 blockers) |

48 hours |

|

Astemizole |

60 days |

|

Ketotifen |

5 days |

|

Tricyclic antidepressants |

2 weeks |

|

Short-term (topical/systemic) steroids |

No effects |

|

Long-term systemic steroids |

2 weeks |

|

Long-term topical steroids |

2-3 weeks |

The advantages of in vitro tests include no

effect of anti-histaminics or steroids, feasibility with any skin

condition and no risk of systemic reactions. Serum sIgE has better

specificity with higher positive predictive value for determining

aeroallergen (pollen and insects) sensitization [21]. SPT have an edge

over in-vitro tests in terms of better sensitivity with clinical

correlation, faster result (15-20 minutes), no interference with high

IgE levels and cost effectiveness [16]. Intradermal tests, with more

risk potential, are indicated only when SPT and/or sIgE results are

negative with relevant exposure history [22].

(ii) Patch test – It is based on

delayed (type IV) hypersensitivity. Patches with allergenic proteins are

applied on the upper back. An eczematous reaction usually occurs after

48-72 hours till as late as 7 days. Optimum reading time is day 2, 4 and

7 after patch application [23]. Test reactions are graded as erythema,

vesiculation or ulceration. TRUE test is one of the commercially

available patches with approximately 30 allergens. The most common

allergens are nickel sulfate, neomycin, myroxylon pereirae (balsam of

Peru), fragrance mix, thiomersal, sodium gold thiosulfate,

quaternium-15, formaldehyde, bacitracin and cobalt chloride [24]. Patch

test can be used at any age with negligible risk of anaphylaxis. It has

high specificity with very low sensitivity and is time consuming.

(iii) Nasal provocation test –

Increasing quantities of allergen extract are introduced in the anterior

part of inferior nasal turbinate to reciprocate the allergic reaction.

Due to higher chances of anaphylaxis and cumbersome technique, this is

not recommended.

(iv) Bronchial (Methacholine) challenge

test – Bronchoconstriction provoked by methacholine can be

quantified by spirometry. It should be done only in hospital setting

with availability of emergency facilities and is rarely performed

now-a-days.

(v) Oral food challenge test – Double

blind placebo control food challenge (DBPCFC) test is the gold standard

technique for detecting sensitivity to suspected food items. However,

due to practical difficulty in masking of food in a vehicle each time,

open label food challenge serves the needful [25]. When sIgE or SPT have

diminished substantially during the course of food allergy or in case of

false positive or negative skin or blood tests, oral challenge can be

used to confirm or rule out allergy.

(vi) Elimination trial test – In case

of true allergy the symptoms should disappear with food elimination and

reappear with its reintroduction [26].

Functional Assessment

Airway Hypersensitivity

Spirometry – Though gold standard for functional

assessment, effort dependence and requirement of patient cooperation

limits its practical utility in younger children and elderly. Evidence

of reversible bronchoconstriction is considered consistent with

diagnosis of asthma.

Impulse oscillometry – Determines airway

resistance, reactance and impedance using sound waves [27]. It can

detect peripheral airway obstruction, with minimal patient’s

cooperation, which may be missed by conventional spirometry [28].

Peak expiratory flow rate – Role limited to

monitor lung functions during domiciliary care. Diurnal variability in

lung functions is consistent with diagnosis of asthma.

Nasal Patency Assessment for Nasal Allergy

Rhino-manometry detects variable resistance

encountered to airstream in nasal passage. Peak nasal inspiratory

flowmeter is an economical, fast, portable, easy to use objective test

with good reproducibility.

Structural Assessment

Nasal endoscopy: It provides accurate assessment

of disease and anatomical variation in patients with symptoms of

rhinitis which may be important during surgical interventions. Apart

from revealing classical signs (watery nasal discharge and edematous

mucosa) it can help in detecting structural deformities (deviated

septum, septal spur, polyps, turbinate hypertrophy and stenotic or

accessary maxillary ostia), ruling out foreign bodies and collecting

samples (for cyto-, microbio- and histopatho-logical examination).

Gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy: It may be

helpful during diagnosis (esophageal edema, furrows, exudates, transient

rings and diffuse narrowing) and management (stricture dilatation) in

eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). Endoscopic guided GI tract biopsy may

provide a vital clue for eosinophilic inflammation.

Supportive Tests

Blood eosinophil levels: Hyper-eosinophilia (>450

cells/mL) may be present in Hodgkin lymphoma, Addison disease, allergies

(including asthma, eczema, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis,

EoE), collagen vascular disorders, drug reactions, mastocytosis,

hyper-eosinophilic syndrome ( ³1500

eosinophils/mL) and infections (HIV, parasitic and fungal infections).

Nasal and sputum eosinophilia: It has been

documented in patients with allergic asthma.

Fractional Exhaled Nitric Oxide (FENO): FENO is a

good surrogate marker for eosinophilic airway inflammation and can

assist in treatment of refractory asthma cases.

Mast cell mediators: High histamine levels soon

after anaphylaxis is the best investigation but practically impossible

due to short half-life (2-3 minutes). Serum tryptase levels peaks

between 15 to 20 minutes (half-life of 2.5 hours.) Blood samples are

collected at 1, 2, 3, 6, 12 and 24-hours post-reaction to document both

rise and fall. A peak concentration of >50 mg/L with relevant symptoms

and documented fall during convalescence is consistent with IgE-mediated

anaphylaxis [29].

Pitfalls of Allergy Testing

The main limitation of allergy testing is that it

detects only IgE-mediated hypersensitivity state, which may not be

clinically relevant. sIgE may be falsely positive with high total IgE

levels. SPT might be falsely negative after certain medications and

anaphylaxis.

Conclusion

Serum and skin tests help in detecting IgE-mediated

hypersensitivities, which require clinical correlation. While choosing

an allergy test panel, one needs to be vigilant about relevant allergens

as per exposure history and cost to benefit ratio for an individual

patient. SPT is a reliable, cost and time effective modality when

performed using standard extracts. Patch test may be useful in delayed

hypersensitivity reactions. Component resolved diagnostics, a futuristic

tool, might be helpful in cross reactive food allergies. ‘Less is more’

should be the dictum, regarding number of allergens to be tested.

Identification of responsible allergens helps in specific allergen

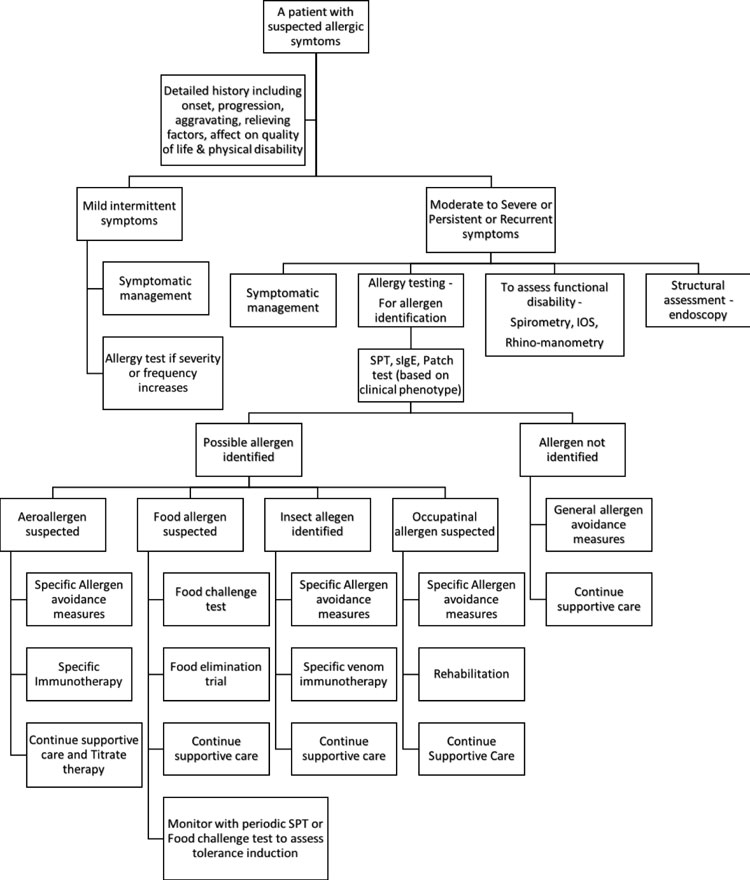

avoidance measures and targeted immuno-therapy. Fig. 2

gives an algorithmic approach to an allergic patient.

|

|

Fig. 2 Approach to an allergic

patient.

|

Contributors: NG: conceptualized and

designed the original manuscript, wrote the initial draft and revised it

critically; PG: helped in designing the initial draft by writing the

immunological part and revised the final manuscript; AS,DG: helped in

designing the original manuscript by writing structural and functional

allergy assessment section and revised it critically for important

intellect. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and

agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: None; Competing interest: None

stated.

|

Key Messages

• Blood tests target free IgE while skin

tests and challenge tests mimic natural reactions by targeting

bound IgE and mast cell degranulation.

• Skin prick test is considered the gold

standard for aero-allergen identification, while challenge tests

take precedence in suspected food allergies.

• Allergy testing is recommended in

moderate-severe or persistent or recurrent symptoms.

• Clinical symptoms, local flora and occupational exposure

should be kept in mind while selecting an allergy panel.

|

References

1. Pawankar R. Allergic diseases and asthma: A global

public health concern and a call to action. World Allergy Organ J.

2014;7:12.

2. Antolin-Amerigo D, Manso L, Caminati M, de la Hoz

Caballer B, Cerecedo I, Muriel A, et al. Quality of life in

patients with food allergy. Clin Mol Allergy. 2016;14:4.

3. Prasad R, Kumar R. Allergy Situation in India:

what is being done? Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2013;55:7-8.

4. Chandrika D. Allergic rhinitis in India: an

overview. Int J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;3:1-6.

5. Pawankar R, Holgate ST, Canonica GW, Lockey RF.

White Book on Allergy. Milwaukee, Winconsin, United State of America.

World Allergy Organization (WAO); 2011.

6. Igea JM. The history of the idea of allergy.

Allergy. 2013;68:966-73.

7. Eastman J, Gupta R, Jose J. Immune Mechanisms.

In: Lee G, Stukus D, Yu Joyce, editors. Review for the Allergy &

Immunology Boards. 3rd ed. Arlington Heights, United States of America.

American College of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (ACAAI); 2016.p.45-6.

8. Sicherer SH, Sampson HA. Food allergy: A review

and update on epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, prevention and

management. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141:41-58.

9. Abraham JT, Barcena MA, Bjelac JA, Pazheri FP.

Specific Diagnostic Modalities. In: Lee G, Stukus D, Yu Joyce,

editors. Review for the Allergy & Immunology Boards, 3rd ed. Arlington

Heights, United States of America. American College of Allergy, Asthma &

Immunology (ACAAI); 2016.p.417-500.

10. Schimke LF, Sawalle-Belohradsky J, Roesler J,

Wollenberg A, Rack A, Borte M, et al. Diagnostic approach to the

hyper-IgE syndromes: immunologic and clinical key findings to

differentiate hyper-IgE syndromes from atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin

Immunol. 2010;126:611-7.

11. de Vos G, Nazari R, Ferastraoaru D, Parikh P,

Geliebter R, Pichardo Y, et al. Discordance between aeroallergen

specific serum IgE and skin testing in children younger than 4 years.

Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2013;110:438-43.

12. Treudler R, Simon JC. Overview of component

resolved diagnostics. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2013;13:110-7.

13. Borres MP, Maruyama N, Sato S, Ebisawa M. Recent

advances in component resolved diagnosis in food allergy. Allergol Int.

2016;65:378-87.

14. Bernstein IL, Li JT, Bernstein DI, Hamilton R,

Spector SL, Tan R, et al. Allergy diagnostic testing: an updated

practice parameter. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;100: S1-148.

15. Kowalski ML, Ansotegui I, Aberer W, Al-Ahmad M,

Akdis M, Ballmer-Weber BK, et al. Risk and Safety Requirements

for Diagnostic and Therapeutic Procedures in Allergology: World Allergy

Organization Statement. World Allergy Organ J. 2016;9:33.

16. Smith W. Skin Prick Testing for the Diagnosis of

Allergic Disease – A Manual for Practitioners. Australasian Society of

Clinical Immunology and Allergy (ASCIA). Available from:

www.allergy.org.au/images/stories/pospapers/ASCIA_SPT_Manual_March_2016.pdf.

Accessed September 26, 2019.

17. Bhattacharya K. Sircar G, Dasgupta A, Gupta

Bhattacharya S. Spectrum of allergens and allergen biology in India. Int

Arch Allergy Immunol. 2018;177:219-37.

18. Comberiati P, Cipriani F, Schwarz A, Posa D, Host

C, Peroni DG. Diagnosis and treatment of pediatric food allergy: an

update. Ital J Pediatr. 2015;41:13.

19. van der Valk JP, Gerth van Wijk R, Hoorn E,

Groenendijk L, Groenendijk IM, de Jong NW. Measurement and

interpretation of skin prick test results. Clin Transl Allergy.

2016;6:8.

20. Haahtela T, Burbach GJ, Bachert C, Bindslev-Jensen

C, Bonini S, Bousquet J, et al. Clinical relevance is associated

with allergen-specific wheal size in skin prick testing. Clin Exp

Allergy. 2014;44:407-16.

21. Alimuddin S, Rengganis I, Rumende CM, Setiati S.

Comparison of specific immunoglobulin E with the skin prick test in the

diagnosis of house dust mites and cockroach sensitization in patients

with asthma and/or allergic rhinitis. Acta Med Indones. 2018;50:125-31.

22. Ferastraoaru D, Shtessel M, Lobell E, Hudes G,

Rosenstreich D, de Vos G. Diagnosing environmental allergies: Comparison

of skin-prick, intradermal, and serum specific immunoglobulin E testing.

Allergy Rhinol (Providence). 2017;8:53-62.

23. Bourke J, Coulson I, English J. Guidelines for

the management of contact dermatitis: an update. Br J Dermatol.

2009;160:946-54.

24. AlSelahi EM, Cooke AJ, Kempe E, Schiffman AB,

Sokol K, Virani S. Hypersensitivity disorders. In: Lee G, Stukus

D, Yu Joyce, editors. Review for the allergy & immunology boards. 3rd

ed. Arlington Heights, United States of America. American College of

Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (ACAAI); 2016.p.129-202.

25. Sampson HA, Aceves S, Bock SA, James J, Jones S,

Lang D, et al. Food allergy: A practice parameter update-2014. J

Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:1016-25.

26. Caffarelli C, Baldi F, Bendandi B, Calzone L,

Marani M, Pasquinelli P, et al. Cow’s milk protein allergy in

children: A practical guide. Ital J Pediatr. 2010;36:5.

27. Shi Y, Aledia AS, Tatavoosian AV, Vijayalakshmi

S, Galant SP, George SC. Relating small airways to asthma control by

using impulse oscillometry in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol.

2012;129:671-78.

28. Dos Santos K, Fausto LL, Camargos PAM, Kviecinski

MR, da Silva J. Impulse oscillometry in the assessment of asthmatic

children and adolescents: From a narrative to a systematic review.

Paediatr Respir Rev. 2017;23:61-7.

29. Sheldon J, Philips B. Laboratory investigation of anaphylaxis:

Not as easy as it seems. Anaesthesia. 2015;70:1-5.

|

|

|

|

|