|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2019;56: 933-937 |

|

Development, Cognition, Adaptive Function and

Maladaptive Behavior in HIV-infected and HIV-exposed Uninfected

Children Aged 2-9 Years

|

|

Sharmila Banerjee Mukherjee 1,

Shilpa Devamare1,

Anju Seth1 and

Savita Sapra2

From Departments of Pediatrics, 1Lady

Hardinge Medical College and associated hospitals; and 2All

India Institute of Medical Sciences; New Delhi, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Sharmila B Mukherjee,

Professor, Department of Pediatrics, Lady Hardinge Medical College and

associated hospitals, New Delhi, India.

Email: [email protected]

Received: March 24, 2019;

Initial review: April 29, 2019;

Accepted: August 03, 2019.

|

|

Objectives: To compare

development/cognition, adaptive function and maladaptive behavior of

HIV-infected and HIV-exposed uninfected children between 2 to 9 years

with HIV-uninfected controls. Methods: This hospital-based

cross-sectional study was conducted from November, 2013 to March, 2015.

50 seropositive HIV-infected, 25 HIV-exposed uninfected and 25

HIV-uninfected children between 2 to 9 years were administered

Developmental Profile 3, Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale 2, and Child

Behavior Checklist for assessing development, adaptive function and

maladaptive behaviour, respectively. Additional data were obtained by

history, examination and review of records. Results:

Significant developmental/cognitive impairment was observed in 38 (76%),

16 (64%) and 6 (24%) HIV-infected, HIV-exposed uninfected, and

HIV-uninfected children, respectively. Significant impairment in

adaptive function was found in 12 (24%) and 2 (8%) HIV-infected and

HIV-exposed uninfected children, respectively. Maladaptive behavior was

not seen in any group. Conclusions: High magnitude of

impaired development/cognition and adaptive function in HIV-exposed and

HIV-infected children warrants assessment of these domains during

follow-up of these children, and incorporation of interventions for

these deficits in standard care for this group.

Keywords: Acquired immunodeficiency disorder,

Developmental delay, Neurocognition, Outcome.

|

|

T

he eco-biodevelopmental framework of child

development conceptualizes that interactions between ecology (social and

physical rearing environments) and biologic processes (heath), determine

developmental trajectories of early childhood. These influence

cognition, adaptive function (skills used in activities of daily living)

and behavior, the effects of which persist in late childhood,

adolescence and even adulthood [1]. Human Immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-

infected children from low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) are

exposed to more adverse factors than high- income countries. These

include non-detection or late detection in pregnancy and infancy,

unavailability of timely anti-retroviral therapy (ART), adverse

environ-mental (malnutrition, micro-deficiencies, decreased

opportunities, poor nurturing care, etc.) and social (i.e.

poverty, parental morbidity, mortality and poor literacy) factors [2,3].

HIV-exposed uninfected children are a less recognized, but equally

vulnerable population who lack HIV-related biological risk factors, but

otherwise face similar adversities.

Previous studies studying development, adaptive

function and behavior of these children from high-income countries

displayed differences varying from no impairment [4] to significant

impairment [5,6]. These discrepancies were explained by heterogeneous

objectives, methodology, participants (age, staging, timing of ART, CNS

drug penetration) and psychometric testing [7]. There is still paucity

of data from LMICs – the available Indian data is restricted to older

children and adolescents [8,9]. As ART policy changes and improving

health care translates into more survivors, there is a need to detect

potential developmental or mental health issues in childhood, for timely

intervention.

This study compared development/cognition, adaptive

function and maladaptive behavior of perinatally-acquired HIV-infected

and HIV-uninfected exposed pre-school and school-aged children with

HIV-uninfected (HU) controls. Their correlation with specific clinical

and environmental factors was determined.

Methods

This hospital-based cross-sectional study was

conducted from November, 2013 to March, 2015, after obtaining

Institutional ethics committee approval. Cases included children aged

2-9 years who were either HIV-infected (seropositive on three

consecutive ELISA rapid tests) or HIV-exposed but uninfected (HIV

negative siblings, or children born to seropositive patients), recruited

from the ART centre of our hospital. Children of the same age-group,

presenting with minor illnesses, were enrolled as controls and

considered to be HIV-uninfected. Exclusion criteria were significant

perinatal events requiring hospitalization, previous neurological

infections, and known neurodevelopmental or chronic disorders.

Sequential enrollment continued till a pre-decided sample size of

convenience (based on ART center attendance of the previous year) was

attained. Parental informed consent was obtained; however, assent of

older children was not taken to avoid inadvertent disclosure.

Locally developed, provider-completed, Hindi

translations of Developmental profile-3 (DP 3) [10], Vineland Adaptive

Behaviour Scale, 2 nd edition

(VABS 2) [11] and Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) [12] were administered

by a trained pediatrician. The parental questionnaire DP 3 assesses

physical, adaptive, social-emotional, cognitive and communication

domains from birth to 12 years. It computes standard scores (SS) for

domains and an overall General Development Score (GDS), which are rated

as Delay, Below average and Average. GDS represents development in

children younger than five years and cognition in older children. VABS 2

is a parental interview that measures adaptive function in

socialization, daily living skills, communication, and motor domains.

Adaptive Behavior Composite (ABC) and SS rate overall and domain-wise

performance as Low, Moderate low, and Adequate. Maladaptive Behavior

Index and Maladaptive Critical Index is assessed in children

ł3 years. CBCL is a

parental interview that categorizes behavior and rates them as Normal,

Borderline and Clinical, based on standardized T scores.

History, examination and records were reviewed after

which psychometric tests were scored. Primary outcome measures included

significant impairment in development/cognition (delay), adaptive

function (low) or maladaptive behavior (significant MBI, MCI or T

scores).

Statisticial analyses: SPSS version 20.0 was used

for statistical analyses. Unpaired t-test and Chi square test were used

for inter-group comparisons. Pearson’s coefficient of correlation (r)

was determined by univariate analysis between individual clinical

(staging, nutritional status, CD4 status, ART, central nervous system

(CNS) penetration) and environmental covariates (socio-economic status,

family composition, parental literacy, HIV and ART status, and death)

and primary outcomes (VABS-2, DP-3 and CBCL scores). Since development

is affected by the cumulative effect of multiple factors, multivariate

analysis was applied between combined clinical and environmental

covariates with the primary outcomes. Strength of association was

measured by multiple correlation coefficient (R).

Results

Of the 113 eligible children, 8 were excluded (3,

epilepsy; 4, significant perinatal events; 5, developmental disorders;

and 1, meningitis). The study population comprised of 50 HIV-infected

children (HI group), 25 HIV-exposed uninfected children (HEU group) and

25 HIV-uninfected (HU group). The mean (SD) age was 4.9 (2.2), 6.1

(1.9), 5.1 (2.2) years and male: female ratio 2.8, 1.1 and 1.1,

respectively in the three groups. Table I displays

baseline participant details in the three groups. Distribution of WHO

clinical staging in HI group was 24 (48%) T1, 12 (24%) T2, 8 (16%) T3

and 6 (12%) T4; 14 (28%) had CD4 percentage <25% while 15 (30%) had CD4

counts <350µl. Forty five (90%) were on ART; 22 (48.9%) with high CNS

penetration and 23 (51.1%) medium CNS penetration. Mean (SD) duration of

ART was 1.2 (0.9) years in children aged 2-5 years and 2 (2) years in

those between 5 and 9 years. None had microcephaly or focal neurological

signs.

TABLE I Baseline Characteristics of Children Enrolled in the Study (N=100)

|

Characteristics |

|

HI (n=50) |

HEU (n=25) |

HU (n=25) |

|

Parental education |

Mother ≤ primary

|

27 (54) |

20 (80) |

7(28) |

|

Father ≤ primary

|

10 (20)

|

8 (32) |

7 (28) |

|

Child education |

No informal (<5 y) |

23/30 (77.7) |

5/7 (71.4) |

7/11 (63.6) |

|

No school (>5 y) |

7/20 (35) |

14/18 (77.7) |

11/14 (78.5) |

|

#Socioeconomic status (SES) |

Lower middle

|

11 (22) |

11 (44) |

9 (36) |

|

Upper lower |

36 (72) |

14 (56) |

12 (48) |

|

Family status |

Nuclear family

|

31 (62) |

20 (80) |

23 (92) |

|

Maternal death |

4 (8) |

1 (4) |

0 |

|

Paternal death |

11 (22) |

2 (8) |

0 |

|

Both death |

4 (8) |

1 (4) |

0 |

|

Anti-retroviral therapy |

Antenatal |

7 (14) |

3 (12) |

- |

|

Maternal |

36 (85.7) |

6 (14.2) |

- |

|

Paternal |

30 (88.2) |

9 (26.5) |

- |

|

Nutritional status |

Severe stunting (<5 y) |

19/30 (63.3) |

0/11 |

0/7 |

|

Severe thinness (>5 y) |

1/20 (5) |

3/18 (16.7) |

4/14 (28.6) |

|

HIV: Human Immunodeficiency, HEU: HIV-exposed uninfected,

HI:HIV-infected, HU: HIV-uninfected; Significant differences (P

<0.05) noted in the following intergroup comparisons:

P<0.05 for children not attending school, Lower Middle SES,

parents on ART and severe s between HI and HEU, Maternal

education, children not attending school, Upper lower SES,

nuclear families and severe stunting – between HI and HU; and

maternal education between HEU and HU; #Using modified

Kuppuswamy socioeconomic status scale (1 child each in Upper

strata in HI and HU groups, and 2 and 3 children in Upper middle

strata in HI and HU groups, respectively). |

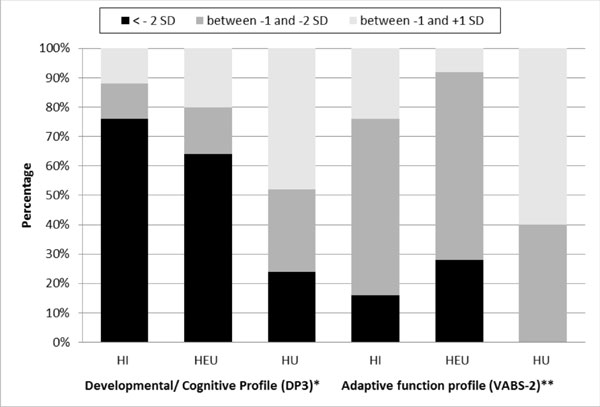

Significant development/cognitive impairment was

observed in 38 (76%) HI, 16 (64%) HEU, and 6 (24%) (SD) HU children.

Mean (SD) GDS of HI and HEU children was significantly lower than HU;

59.2 (16.9), 70.1(13.4) and 77.4(13.4), respectively. Significant

adaptive impairment was seen in 12 (24%) HI and 2 (8%) of HEU children.

Mean (SD) ABC of HI group was significantly lower than HEU group and HU

group [75.3 (8.9) vs 85.5 (7.3), P<0.05].

|

|

Fig. 1 Distribution of levels of

performance of development/cognition and adaptive function in

HIV-infected (HI), HIV-exposed and uninfected (HEU) and

HIV-uninfected (HU) groups.

|

Distribution of levels of development/cognition and

group [75.3 (8.9) vs 85.4 (7.3), P<0.05] adaptive function

is depicted in Fig. 1, and domain-wise performance in

Web Table I. Significant maladaptive behavior was not

observed in any group. Mean (SD) MBI was 11.7 (1.9), 11.4 (1.1) and 11.2

(1.1) in the HI, HEU and HU group, respectively. The mean (SD) CBCL T

score of HI group [29.2 (6.1)] was significantly higher than HEU group

[26.0 (1.7)] and HU [26.6 (1.8)] children, but not clinically relevant.

No single independent clinical or environmental

covariate had a strong correlation with GDS, ABC or T scores in HI

group. Combined clinical covariates displayed strong and significant (P<0.05)

association with GDS (R=0.84), ABC (R 0.81) and T scores (R 0.73).

Association between combined environmental covariates and GDS was strong

in HI (R=0.73, P<0.05) and HEU (R=0.74, P<0.05), moderate

with ABC in HI (R=0.59, P<0.05) and HEU (R=0. 66, P<0.05),

and weak with ABC in HU (R= 0.45, P<0.05).

Discussion

We found that the group as a whole had poor maternal

literacy, low pre-school/ school attendance, and thinness. A strong and

significant association was found between combined environmental factors

and overall develop-ment (GDS). The high prevalence of impairment in our

controls is less than the estimated 43% of children under five years

from LMIC who are not expected to attain their developmental potential

[13].

Significant cognitive impairment and low scores in

developmental and adaptive function was seen in HIV-infected children.

Studies from LMIC [4,5,14] have reported this earlier, attributing it to

delayed ART (more severe and pervasive neurological damage) and adverse

ecological and biological factors [15]. Neurodevelop-mental outcomes are

better when ART is started in infancy, as it decreases irreversible CNS

damage [5]. Though 90% of children in this study were receiving ART,

initiation in infancy had not been universal due to the then existing

ART policy. Adaptive function in HI children is affected by co-morbid

illnesses, increased dependence on caregivers, decreased opportunities,

and poor parental support, besides CNS dysfunction [16]. This explains

the significant differences between HIV-infected and HIV-exposed

uninfected children with respect to proportion, severity of impairment

and strength of association between environmental factors and ABC.

Children in HEU group had more cognitive impairment

than controls, and a strong association with combined environmental

covariates. This was also observed by Bass, et al. [2] in Ugandan

children. Surprisingly, few studies from high-income countries report

equal or even higher impairment in HEU group than HIV-infected children

[8]. This phenomenon is explained by HI group children receiving high

quality medical, nutritional, and social support, while HIV-exposed but

uninfected counterparts remain unsupported. The increased maladaptive

behavior reported in older HIV- infected children and adolescents

[8,16-19] is attributed to psychological responses to debilitating

illness and disclosure. The absence of maladaptive behavior in our study

may be attributed to less severe disease in the majority, non-disclosure

and good medical care (90% on ART, good adherence to therapy,

nutritional support and regular follow-up), all of which promote

resilience [4].

Though the Hindi translations of the psychometric

tools have not been validated in Indian community, they are routinely

used in clinical practice and research. The lack of Indian norms was

addressed by including a demographically-matched control group. Other

limitations were small sample size (being single centric) and lack of

blinding. An attempt was made to decrease information bias by

interpreting the tests after collection of clinical data. An adequately

powered, multi-centric, longitudinal study with age stratification is

recommended to provide deeper insight.

In India, ART became universally available to all

HIV-infected children after a policy change in 2014 [20]. Its clinical

implications are earlier initiation of ART and more children surviving

till adolescence and adulthood. Though biological HIV-related risk

factors may decrease, the ecological adverse influence will remain with

their associated impact of cognition, adaptive function and behavior. We

suggest that the National AIDS Control Organization consider

incorporating their assessment in standard care of all HIV-exposed

children, whether infected or not.

Contributors: SBM,AS: conceptualized the

study and will stand as guarantors; SD,SBM: did the literature search;

SD: was trained to administer the psychometric tools by SBM and SS and

collected the data; SBM,SD,SS: interpreted and analyzed the data; SM:

drafted the manuscript which underwent a critical appraisal by SD,AS,SS.

All the authors approved the final manuscript and agree to be

accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions

related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are

appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: None; Competing interests:

None stated.

|

What This Study Adds?

• Impairment in development/cognition and adaptive

function was found in HIV-infected and HIV-exposed

uninfected children aged 2-9 years.

|

References

1. Fiegelman S. Overview of assessment and

variability: Growth, development and behavior. In: Kliegmen RM,

Stanton BF, St Geme III JW, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics.

20th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2016. p. 48-51.

2. Bass JK, Nakasujja N, Familiar-Lopez I, Sikorskii

A, Murray SM, Opoka R, et al. Association of caregiver quality of

care with neurocognitive outcomes in HIV affected children aged 2-5

years in Uganda. AIDS Care. 2016;28:76-83.

3. Coscia JM, Christensen BK, Henry RR, Wallston K,

Radcliffe J, Rutstein R. Effects of home environment, socioeconomic

status, and health status on cognitive functioning in children with

HIV-1 infection. J Pediatr Psychol. 2001;26:321-9.

4. Smith R, Chernoff M, Williams PL, Malee KM, Sirios

PA, Kammerer B, et al. Impact of HIV severity on cognitive and

adaptive functioning during childhood and adolescence. Pediatr Infect

Dis J. 2012;31:592-8.

5. Puthanakit T, Aurpibul L, Louthrenoo O, Tapanya P,

Nadsasarn R, Insee-ard S, et al. Poor cognitive functioning of

school-aged children in Thailand with perinatally acquired HIV infection

taking antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2010;24:141-6.

6. Brahmbhatt H, Boivin M, Ssempijja V, Kigozi G,

Kagaayi J, Serwadda D, et al. Neurodevelopmental benefits of

Anti-Retroviral Therapy in Ugandan children 0–6 Years of age with HIV. J

Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;67:316-22.

7. Laughton B, Cornell M, Boivin M, Van-Rie A.

Neurodevelopment in perinatally HIV-infected children: a concern for

adolescence. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:18603.

8. Grover G, Pensi T, Banerjee T. Behavioural

disorders in 6-11-year-old, HIV-infected Indian children. Ann Trop

Paediatr. 2007;27:215-24.

9. Joshi D, Tiwari MK, Kannan V, Dalal SS, Mathai SS.

Emotional and behavioural disturbances in school going HIV positive

children attending HIV clinic. Med J Armed Forces India. 2017;73:18-22.

10. Gerald D. Developmental Profile, 3rd ed. Los

Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 2007.

11. Sparrow S, Cicchetti DV, Balla D. Vineland

adaptive behavior scale, 2nd ed. San Antonia: Pearson Assessment; 2005.

12. Achenbach TM, Rescorta LA. Manual for the ASEBA

school age forms and profiles. Burlington, VY: University of Vermont;

2001.

13. Black MM, Walker SP, Fernald LCH, Anderson CT,

DiGirolomo AM, Chunling L, et al. Early childhood development

coming of age: Science through the life course. Lancet. 2017;389:77-90.

14. Nozyce M, Lee S, Wiznia A, Nachman S, Mofenson L,

Smith M, et al. A behavioral and cognitive profile of clinically

stable and HIV infected children. Pediatrics. 2006;117:763-70.

15. Boyede GO, Lesi FEA, Ezeaka VC, Umeh CS. The

influence of clinical staging and use of antiretroviral therapy on

cognitive functioning of school aged Nigerian children with HIV

infection. J AIDS Clin Res. 2013;4:195.

16. Malee KM, Tassiopoulos K, Huo Y, Siberry G,

Williams PL, Hazra, R, et al. Mental health functioning among

children and adolescents with perinatal HIV infection and perinatal HIV

exposure. AIDS Care. 2011;23:1533-44.

17. Martin SC, Wolters PL, Toledo-Tamula MA, Zeichner

SL, Hazra R, Civitello L. Cognitive functioning in school aged children

with vertically acquired HIV infection being treated with Highly active

antiretroviral therapy (HAART). Dev Neuropsychol. 2006;30:633-57.

18. Gadow KD, Chernoff M, Williams PL, Brouwers P,

Morse E, Heston J. Co-occurring psychiatric symptoms in children

perinatally infected with HIV and peer comparison sample. J Dev Behav

Pediatr. 2010;31:116-28.

19. Gosling A, Burns J, Hirst F. Children with HIV in

the UK: A longitudinal study of adaptive and cognitive functioning. Clin

Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;9:25-37.

20. National AIDS Control Organization. NACO Annual

Report 2013-14. Available from:

http://naco.gov.in/documents/annual-reports. Accessed

December 27, 2015.

|

|

|

|

|