|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2018;55: 993- 994 |

|

Neuroschistosomiasis: An Unusual

Intracranial Space Occupying Lesion

|

|

Nevitha Athikari Manamal 1,

Tanu Singhal2,

Abhaya Kumar3,

Darshana Sanghvi4

and Jayanti Mani5

From Departments of 1Laboratory Medicine,

2Pediatrics, 3Neurosurgery, 4Radiology

and 5Neurology, Kokilaben Dhirubhai Ambani Hospital and

Medical Research Institute, Mumbai, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Tanu Singhal, Department of

Paediatrics, Kokilaben Dhirubhai Ambani Hospital and Medical Research

Institute, Mumbai 400 053, India.

Email: tanusinghal@yahoo.com

Received: October 22, 2017;

Initial Review: February 15, 2018;

Accepted: May 24, 2018.

|

Background: Neuroschistosomiasis

is an uncommonly reported disease. Case characteristics: An

adolescent Indian boy residing in Kenya presented with headache, visual

symptoms and seizures, with MRI showing space-occupying lesions in the

occipital lobe and cerebellum. Observation: Brain biopsy was

diagnostic of neuro-schistosomiasis; complete recovery was seen with

praziquantel and corticosteroid therapy. Message: This case

highlights the importance of considering epidemiology in differential

diagnosis and establishing definitive diagnosis even if it is by

invasive methods.

Keywords: Headache, Raised intracranial pressure, Schistosoma

hemotobium, Seizures.

|

|

S

chistosomiasis; although widely prevalent

worldwide [1,2], is rarely reported from India due to the absence of the

specific intermediate snail hosts [3]. Acute neuroschistosomiasis,

usually due to S. japonicum, presents as acute

meningo-cencephalitis, whereas, chronic neuroschistosomiasis results

from ectopic migration of the eggs from the portal mesenteric or pelvic

systems to the CNS leading to a granulomatous reaction to the eggs. [4].

These can present as Pseudotumoral encephalic schistosomiasis due to

S. japonicum, or Spinal cord schistosomiasis in S. mansoni/ S.

hematobium [4]. We describe here a case of neuroschistosomiasis in a

non-resident Indian adolescent living in Kenya.

Case Report

This 17-year-old boy of Indian origin residing in

Nairobi, Kenya had been experiencing headaches, light headedness and

episodes of blurred vision for two months before admission. He also

reported episodes of flickering balls of light in front of his eyes that

came on randomly multiple times a day and left behind a dull occipital

headache. There was no fever, weight loss or cough. Magnetic resonance

imaging (MRI) done in Kenya showed space occupying lesions in the right

occipital parenchyma and left cerebellum. He presented to our hospital

with a tonic clonic seizure. The physical examination was normal.

Antiepileptic therapy with levetiracetam was initiated.

Radiologic differentials of lymphoma, autoimmune

vasculitis and tuberculosis were considered. Initial investigations

revealed a normal complete blood count, ESR and CRP, and negative ANA

and ANCA. CSF study including a TB PCR was negative. A contrast enhanced

CT scan of the chest and abdomen done to look for extra CNS TB was

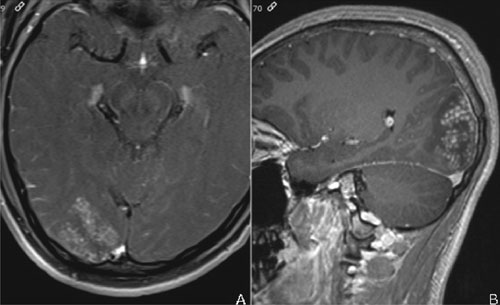

normal. Repeat MRI showed mild interval progression (Fig. 1).

Again seen were focal mass- like lesions in the right occipital lobe and

left cerebellum with prolonged T1- and T2-signal and perilesional

vasogenic edema. The lesions had ill-defined and irregular margins with

heterogenous enhancement. Arborised linear enhancement with interspersed

enhancing punctate nodules was seen. Punctate nodules formed the larger

conglomerate masses. As the diagnosis could not be established through

indirect and surrogate tests, an occipital craniotomy was done and brain

biopsy taken.

|

|

Fig. 1 Axial (a) and sagittal (b) T1

weighted contrast MRI shows conglomerate nodular and linear

enhancing nodules with arborization.

|

On histopathology, the brain parenchyma showed

granulomatous inflammation with numerous well-formed granulomas composed

of epithelioid cells, multinucleate giant cells and central necrosis.

The periphery showed lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate along with eosinophils.

The center of many granulomas showed one or two non-operculated

refractile eggs/ova of trematode with terminal spine (Web Fig.

1). Few ova show ruptured and distorted morphology engulfed by giant

cells. No vasculitis or viable larvae of parasite were seen. Thus a

tentative diagnosis of schistosomiasis was made. The ova morphology with

a terminal spine resembled S. hematobium. The images were sent to

the Department of Parasitic Diseases at Centers for Disease Control,

Atlanta, USA where the diagnosis was confirmed.

On enquiry, the patient who was an avid swimmer gave

a history of frequent swimming in natural fresh water lakes in Kenya.

There was no history of urinary or intestinal symptoms, and his urine

and stool analysis were negative for parasitic eggs. His serum was

positive for schistomiasis by hemagglutination (2560, reference range

<160), ELISA (6.8, reference range <0.8 negative, 0.8-1.2 equivocal and

>1.2 positive) as well as Western Blot (positive for the p30-32 / p20-24

bands)

The patient was started on praziquantel at a dose of

40 mg/kg/day for 3 days along with dexamethasone 4 mg thrice daily which

was subsequently tapered over 1 month. His clinical symptoms resolved

completely and a repeat MRI after 2 weeks showed remarkable regression

of the CNS lesions. The boy was asymptomatic at the six-month follow-up,

and a repeat MRI was normal.

Discussion

Neuroschistosomiasis is commoner than perceived,

diagnosed or reported [4-6]. An autopsy study from Africa reported that

half the patients with urinary schistosomiasis had brain lesions [7].

Another pathological study in Africa found scattered ova of S.

haematobium or S. mansoni in the brain at autopsy in around

25% of 150 unselected cadavers [5]. Only a handful of cases of

indigenous urinary schistosomiasis have been reported from India, but

none of neuroschistosomiasis [3].

In the index case, commoner differentials like

tuberculosis, lymphoma, and autoimmune etiology were considered, but

biopsy revealed the rare etiology. Even in most cases reported from

endemic areas, the diagnosis is usually made inadvertently following

brain biopsy and lesion excision. This is because the clinical symptoms

of the disease are non-specific and mimicked by other infectious and

non-infectious illnesses, including tumors. Some investigators have

described arborised linear enhancement circled by multiple enhancing

punctuate nodules as more characteristic for schistosomiasis [8]. CSF

findings are also non-specific. Recent studies have reported on the

utility of specific schistosoma serology and PCR in CSF for diagnosis

[9]. In some cases, the speciation was done by PCR analysis of brain

tissue [5].

Treatment of chronic neuroschistosomiasis is not well

standardized but good results with combination therapy with praziquantel

and steroids [4] are reported. Current consensus is to reserve surgery

only for non-responding lesions, severely elevated intracranial pressure

and intractable epilepsy [10]. This case highlights the need to consider

epidemiology in clinical differential diagnosis of any illness as well

as the importance of establishing a definitive diagnosis even if it is

by highly invasive methods.

Acknowledgements: CDC (Centre for Disease

Control) DPD MDPDx team for confirmation of diagnosis and Dr Francois

Cornu from Eurofins, Biomnis, France.

Contributors: NAM: histopathologic diagnosis and

drafted the manuscript; TS: treatment and finalized the manuscript; AK:

performed the craniotomy and lesion excision and contributed to writing

the manuscript; DS: reported on the MRI and wrote parts of the

manuscript; JM: involved in clinical care of the patient and contributed

to the manuscript.

Funding: None; Competing interest: None

stated.

References

1. Gryseels B, Polman K, Clerinx J, Kestens L. Human

schistosomiasis. Lancet. 2006; 368: 1106-18.

2. WHO fact sheet updated January 2017. Available

from:

http://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/schistosomiasis.

Accessed June 12, 2017.

3. Kali A. Schistosome infections: An Indian

perspective. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9:DE01-4.

4. Ferrari TC, Moreira PR. Neuroschistosomiasis:

Clinical symptoms and pathogenesis. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10: 853-64.

5. Imai K, Koibuchi T, Kumagai T, Maeda T, Osada Y,

Ohta N, et al. Cerebral schistosomiasis due to Schistosoma

haematobium confirmed by PCR analysis of brain specimen. J Clin

Microbiol. 2011;49:3703-6.

6. Pollner JH, Schwartz A, Kobrine A, Parenti

DM. Cerebral schistosomiasis caused by Schistosoma haematobium: Case

Report. Clin Infect Dis.1994;18:354-7.

7. Alves W. The distribution of schistosoma eggs in

human tissues. Bull World Health Organ. 1958;18:1092-97.

8. Liu H, Lim CC, Feng X, Yao Z, Chen Y, Sun H, et

al. MRI in cerebral schistosomiasis: Characteristic nodular enhance-ment

in 33 patients. Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:582-8.

9. Härter G, Frickmann H, Zenk S, Wichmann D, Ammann

B, Kern P, et al. Diagnosis of neuroschistosomiasis by antibody

specificity index and semi-quantitative real-time PCR from cerebrospinal

fluid and serum. J Med Microbiol. 2014;63:309-12.

10. Zhu F, Huang X, Wu M, Jin WX, Xie K. Diagnosis and treatment of

cerebral schistosomiasis: A report of 166 cases. Zhongguo Xue Xi Chong

Bing Fang Zhi Za Zhi. 2014;26: 695-6.

|

|

|

|

|