|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2018;55:989-992 |

|

Meta-analysis

Evaluating Efficacy and Safety of Levetiracetam for the

Management of Seizures in Children

|

|

Source Citation: Zhang L, Wang C, Li

W. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials on levetiracetam in

the treatment of pediatric patients with epilepsy. Neuropsychiatr Dis

Treat. 2018;14:769-79.

Section Editor: Abhijeet Saha

|

|

Summary

This meta-analysis was conducted to evaluate clinical

efficacy, safety and tolerability of levetiracetam as mono- or

adjunct-therapy in the treatment of children and adolescents with

epilepsy. A total of 1,013 patients were included from 13 randomized

controlled trials (RCTs). Levetiracetam had a comparable seizure-free

rate (RR 1.16, 95% CI 1.03, 1.31; P=0.30) compared to other

anticonvulsants (oxcarbazepine, valproate, sulthiame, carbamazepine) or

placebo. Seizure-frequency reduction of (>50% from baseline)

levetiracetam was equivalent (RR 1.08, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.16; P=0.35)

to other antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) with a comparable side effect

profile (RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.77, 1.06). The authors concluded that

levetiracetam had comparable efficacy, tolerability and adverse effect

profile compared to others AEDs, and advocated more well-designed trials

to justify widespread use of levetiracetam.

Commentaries

Evidence-based Medicine Viewpoint

Relevance: In recent years, levetiracetam has

gained popularity for treating seizure disorders in adults and children.

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE)

guidelines in the United Kingdom recommended it as an add-on medication

for certain types of seizures such as partial seizures, myoclonic

seizures, and a limited number of other specific causes of childhood

seizures [1]. This is probably because the mechanism of anti-convulsant

action of levetiracetam is different from other medications. Its other

pharmacological properties, including near-complete absorption after

oral intake, minimal metabolism, and absence of drug interactions make

it attractive for clinical use. A recently published Cochrane review [2]

undertook a network meta-analysis to examine the comparative therapeutic

efficacy of ten AEDs. Although the review was not targeted to children

alone, it concluded that medications like phenobarbitone or phenytoin

had greater efficacy than newer agents, but these were also associated

with the highest risk of non-compliance compared to lamotrigine or

levetiracetam. Overall, the network meta-analysis suggested that

valproate is the drug of choice for generalized tonic-clonic seizures,

while lamotrigine or levetiracetam are other appropriate options.

Similarly, in partial seizures, carbamazepine and lamotrigine are

appropriate as initial therapy; although, levetiracetam could be an

option. Another systematic review [3] evaluating levetiracetam

monotherapy in children included 32 studies with various study designs,

but failed to find convincing evidence to support levetiracetam in

preference to other medications. A fairly recent systematic review

explored the safety profile of levetiracetam in children [4], and

identified a higher (but statistically insignificant) prevalence of

behavioral problems as well as drowsiness. Another systematic review in

adults and children also confirmed that the adverse event profile of

levetiracetam affected compliance to treatment [5]. Against this

background, this new systematic review focusing on the efficacy and

safety of levetiracetam in children has been published [6].

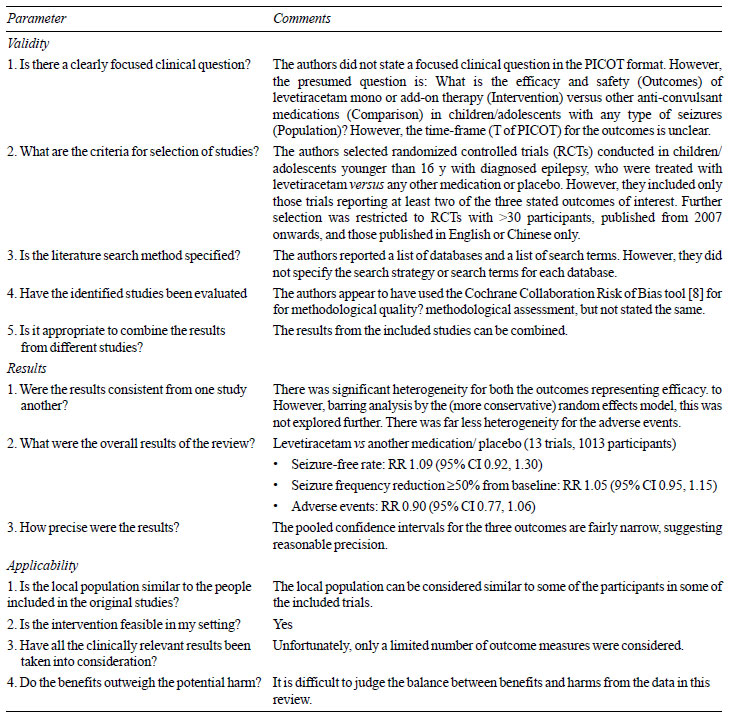

Critical appraisal: Table I

summarizes critical appraisal of the systematic review using one of

several tools available for the purpose [7]. However, several additional

issues emerged. It appears that the authors were more focused on the

meta-analysis component, rather than the systematic review of

literature. This is also reflected in the title’s emphasis on

meta-analysis, instead of the review itself. It should be clarified that

meta-analysis is only one component of systematic reviews, and

represents a statistical tool for pooling the results across included

studies to obtain a summary estimate of effect. Therefore, if the

systematic review is not conducted properly, the meta-analysis can be

flawed.

|

TABLE I Critical Appraisal of the

Systematic Review

|

|

In this review [6], the authors applied several

restrictions to their literature search that have not been properly

justified. For example, trials were included only if they reported two

specific outcome measures of therapeutic efficacy viz

seizure-free rate and >50% frequency reduction from baseline.

This restriction limited the scope of considering trials with other

outcome measures of efficacy, such as seizure-free period, time to

seizure recurrence, time to withdrawal of medication, and

³75% frequency

reduction from baseline. Similarly, adverse events were represented in a

single outcome without emphasizing on serious events, and those leading

to therapy discontinuation. Thus, coupled with a single outcome measure

on adverse events, there were only three outcome measures in this

review. Further, the authors included only those RCTs reporting at least

two of these three outcomes. This reflects bias.

Although the review was focused on the pediatric age

group, only trials including children younger than 16 years of age were

included, and no justification for excluding children between 16 to 18

years was provided. Another serious restriction was the exclusion of

trials with less than 30 participants. These arbitrary restrictions

resulted in the exclusion of a trial by Rosenow, et al. [9]

comparing levetiracetam versus lamotrigine. The fact that this

trial included 33 children upto 17 years of age makes one wonder whether

arbitrary restrictions in this review [6] were designed to exclude this

trial [9]. Unfortunately, the authors did not present a ‘Table of

excluded studies’ for readers to judge whether any other eligible trials

were unfairly excluded. The ‘Table of Included studies’ [6] lacks

information on whether levetiracetam was used as mono- or polytherapy,

and whether it was the initial treatment or add-on treatment. Similarly,

the duration of therapy was also not described. These are important to

judge the clinical utility of levetiracetam.

Conference abstracts were completely excluded from

the review without providing a justification. Similarly, the language

restriction in the review without specifying reasons is also arbitrary;

although, this could be related to resource constraints and the focus on

applicability in the local population.

On the other hand, the authors decided not to

restrict inclusion of RCTs based on duration of treatment and/or

follow-up. This permitted the inclusion of three trials with very short

follow-up periods ranging from 5 days to 12 weeks. It is interesting

that all three were placebo-controlled, and together showed

statistically significant benefit with levetiracetam.

The authors did not explore heterogeneity observed in

the meta-analyses. It is essential to understand whether the efficacy of

levetiracetam differed on the basis of duration of treatment, baseline

clinical diagnosis, compliance to therapy, mono- or polytherapy, initial

or add-on agent, etc. The table showing quality assessment of the

included RCTs reported ‘very serious limitations’ for all three outcomes

despite the absence of any serious inconsistency, indirectness or

imprecision. However, no explanation was provided for this. Although

publication bias was assessed, the results were not presented.

The overall presentation of the systematic review [6]

has considerable room for improvement. For example, the text stated that

levetiracetam was superior to placebo for both the outcome measures

reflecting therapeutic efficacy. However, the two forest plots reflect

the exact opposite result, showing that placebo was superior to

levetiracetam. The Discussion section is heavily loaded with a

repetition of the results, without alluding to the existing systematic

reviews on the topic or the additional value of this review. On a

lighter note, data extraction was done in an ‘electric’ rather than

‘electronic’ format – a minor point that probably escaped the attention

of the editorial process.

Usually, events in RCTs are counted in terms of the

unfavorable outcome (i.e., treatment failure), rather than

favorable outcome (i.e., treatment success). Thus, in this review

[6], failure of seizure control and failure to achieve >50%

reduction in seizure frequency would be the conventional expression of

the outcome measures. Reversing the convention affects calculation of

relative risks as shown in Table II. Further, the dramatic

efficacy compared to placebo was considerably blunted.

Table II Comparison of Levetiracetam Efficacy by Expression of Outcome Measures

(Risk Ratio, Random Effects Model)

|

Review by Zhang [6]

|

Re-analysis of data

|

Review by Zhang [6]

|

Re-analysis of data

|

|

Event: Seizure-free

|

Event: Absence of |

Event: Seizure-free reduction |

Event: Absence of seizure-free

|

|

rate |

seizure-free state |

³50% from baseline

|

reduction ³50% from baseline |

|

vs Oxcarbazepine |

1.09 (0.95, 1.25) |

0.93 (0.72, 1.20) |

1.00 (0.93, 1.09) |

1.06 (0.69, 1.64) |

|

vs Placebo |

4.25 (1.92, 9.45) |

0.77 (0.61, 0.98) |

1.79 (1.26, 2.53) |

0.73 (0.62, 0.86) |

|

vs Sulthiame |

0.89 (0.70, 1.14) |

2.10 (0.43, 10.26) |

0.89 (0.70, 1.14) |

2.10 (0.43, 10.26) |

|

vs Valproate |

1.11 (0.88, 1.40) |

0.94 (0.80, 1.11) |

1.08 (0.93, 1.25) |

0.60 (0.25, 1.44) |

|

vs Carbamazepine |

0.64 (0.36, 1.16) |

1.49 (0.87, 2.54) |

0.76 (0.50, 1.15) |

1.65 (0.77, 3.53) |

|

Pooled estimate |

1.09 (0.92, 1.30) |

0.87 (0.77, 1.00) |

1.05 (0.95, 1.15) |

0.83 (0.67, 1.02) |

Extendibility: The clinical problem, type of

patients, therapeutic options and choice of medication administered, are

all extendible to our settings. Therefore, had this review been free

from the bias(es) highlighted, the results could have been considered

for application.

Conclusion: This systematic review [6] has

several methodological limitations that limit the confidence in the

reported results that levetiracetam has comparable efficacy and safety

with respect to other AEDs in children.

Funding: None; Competing interests: None

stated.

Joseph L Mathew

Department of Pediatrics,

PGIMER, Chandigarh, India.

Email:

[email protected]

References

1. National Institute for Health and Clinical

Excellence. The epilepsies: the diagnosis and management of the

epilepsies in adults and children in primary and secondary care 2012.

Available from: guidance.nice.org.uk/cg137. Accessed October 15,

2018.

2. Nevitt SJ, Sudell M, Weston J, Tudur Smith C,

Marson AG. Antiepileptic drug monotherapy for epilepsy: a network

meta-analysis of individual participant data. Cochrane Database Syst

Rev. 2017;6:CD011412.

3. Weijenberg A, Brouwer OF, Callenbach PM.

Levetiracetam monotherapy in children with epilepsy: A systematic

review. CNS Drugs 2015;29:371-82.

4. Egunsola O, Choonara I, Sammons HM. Safety of

levetiracetam in paediatrics: A systematic review. PLoS One.

2016;11:e0149686.

5. Verrotti A, Prezioso G, Di Sabatino F, Franco V,

Chiarelli F, Zaccara G. The adverse event profile of levetiracetam: A

meta-analysis on children and adults. Seizure. 2015;31: 49-55.

6. Zhang L, Wang C, Li W. A meta-analysis of

randomized controlled trials on levetiracetam in the treatment of

pediatric patients with epilepsy. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat.

2018;14:769-79.

7. Abalos E, Carroli G, Mackey ME, Bergel E. Critical

appraisal of systematic reviews Available from: http://apps.who.int/rhl/Critical%20appraisal%20of%20

systematic%20reviews.pdf. Accessed December 14, 2016.

8. Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool (modified) for Quality

Assessment of Randomized Controlled Trials. Available from:

http://www.tc.umn.edu/~msrg/caseCATdoc/rct.crit. pdf. Accessed

November 20, 2017.

9. Rosenow F, Schade-Brittinger C, Burchardi N, Bauer

S, Klein KM, Weber Y, et al. The La Li Mo Trial: lamotrigine

compared with levetiracetam in the initial 26 weeks of monotherapy for

focal and generalized epilepsy- an open-label, prospective, randomised

controlled multicenter study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry.

2012;83:1093-8.

Pediatric Neurologist’s Viewpoint

Levetiracetam (LEV) has been the drug most widely

used off-label in pediatric population for past decade and half.

Initially FDA-approved as an adjunctive anti-epileptic drug (AED) for

adults with partial epilepsy, it was later approved for children with

partial-onset seizures (above 4 years of age), myoclonic seizures (6

years and older) and generalized tonic-clonic seizures (12 years and

older) [1]. In 2012, it was approved for usage in infants from 1 month

of age. It was welcomed with open arms by Neurologists caring for

infants and children, with hopes of efficacious seizure control with

novel mechanism of action and minimal adverse effects. The meta-analysis

by Zhang, et al. [2] brings out many pertinent issues to light –

good and bad – with Levetiracetam usage in children. The vast number of

studies/publications excluded (over 1000) in the meta-analysis

highlights its widespread use. On the flip side, only13 eligible studies

(8 from China) also points to lack of good quality evidence on its

efficacy and adverse events. Although LEV was more effective than

placebo, and equally effective as other AEDs (Valproate, Carbamazepine,

Sulthiame, Oxcarbazepine), in reducing seizures by >50%, it has not

shown superiority over other AEDs or placebo in terms of 100%

seizure-free rate. In the subgroups, LEV was slightly better in children

with Rolandic epilepsy than other partial epilepsies, but this was not

statistically significant. The adverse events were also similar to other

AEDs. There are lot of limitations in interpreting this data: large

heterogeneity of studies with differing sample sizes, variable intervals

for efficacy estimation, heterogeneity of epilepsies studied etc.

With the available studies, it is difficult to make any meaningful

conclusions about the efficacy of LEV from this review. As epilepsies in

infants and children are diverse, it is hoped that homogenous

populations (e.g., epileptic spasms, benign focal epilepsies,

primary generalized epilepsies, infantile-onset epilepsies of unknown

etiology, focal epilepsies of structural etiology) are studied in

future, with clinically meaningful intervals for end-point estimation.

For now, it’s a long way before LEV can be accorded prime position in

pediatric AED armamentarium based on current evidence.

Funding: None; Competing interests: None

stated.

Ramesh Konanki

Consultant Pediatric Neurologist

Rainbow Hospital for Women and Children,

Hyderabad, India.

Email: rameshkonanki@gmail.com

References

1. Weijenberg A, Brouwer OF, Callenbach PM.

Levetiracetam monotherapy in children with epilepsy: a systematic

review. CNS Drugs. 2015;29 :371–82.

2. Zhang L, Wang C, Li W. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled

trials on levetiracetam in the treatment of pediatric patients with

epilepsy. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018;14:769-79.

|

|

|

|

|