|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2018;55:975-978 |

|

Growth Patterns in

Small for Gestational Age Babies and Correlation with

Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 Levels

|

|

Deepika Rustogi 1,

Sangeeta Yadav1,

Siddarth Ramji2

and TK Mishra3

From Departments of 1Pediatrics, 2Neonatology

and 3Biochemistry, Maulana Azad Medical College (University

of Delhi), New Delhi, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Sangeeta Yadav, Director

Professor, Head, Department of Pediatrics, Maulana Azad Medical College,

New Delhi, India.

Email:

[email protected]

Received: August 03, 2017;

Initial review: December 26, 2017;

Accepted: August 27, 2018.

|

Objective: Correlation of catch-up growth and Insulin-like

Growth Factor -1 levels (IGF-I) in SGA babies. Methods: 50

Full-term Small for Gestational Age children aged 12-18 months were

analyzed for Catch-up growth (gain in weight and/or length, Standard

Deviation Score/SDS >0.67). IGF-1 was measured after post-glucose load

using ELISA method and correlated with catch-up growth. Results:

Mean (SD) birthweight and length were 2.1 (0.3) Kg and 44.4 (3.1) cm,

respectively. At enrollment, mean (SD) age, weight and length were 15.0

(2.1) months, 7.7 (1.3) Kg, and 72.9 (5.6) cm, respectively. Catch-up

growth was noted in 60% children. IGF-1 levels were significantly higher

in children showing catch-up growth (56.6 (63.2) ng/mL) compared to

those not having catch up growth (8.7 (8.3) ng/mL). IGF-1 was positively

correlated with both weight and length catch-up. Conclusion:

Majority of Small for Gestational Age showed catch-up growth by 18

months, which had good correlation with IGF-1 levels.

Keywords: Inslin sensitivity, Low birthweight, Outcome,

Postnatal Growth.

|

|

M

ajority of small for gestation (SGA) infants show

rapid weight/length gain in early postnatal life [1-3], known as

catch-up growth. In almost 90%, it is achieved by the age of 2 years;

however, 10-15% continue to experience poor growth

[1-4]. The patterns of these weight and length

catch-up growth are regulated by genetically determined, pre-programmed,

intrinsic ability of the growth plate that is coordinated by important

biological regulators including GH-IGF 1 system, Insulin, Thyroxine,

Cortisol, Leptin, Sex steroids, and nutrition - as explained by the

Neuroendocrine hypothesis [4]. So, changes in IGF system coincide with

the postnatal catch up growth, as IGF-I levels increase rapidly from

birth in SGA [5,6].

Epidemiological studies have pointed out a link between being born

SGA/IUGR and later risk of development of non-communicable diseases [7],

the linkage between these associations could be due to alterations in

the programming of insulin, IGF-1 and IGF-2.

No studies have been conducted on the role of IGF-1

in SGA and catch-up growth in our population. Therefore, this study was

carried out to study the growth patterns and its correlation with IGF-1

levels in term SGA children.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional study conducted in the

Department of Pediatrics of a tertiary-care center. All children aged

between 12-18 months attending the follow-up clinic in pediatric OPD

from October 2009 to January 2012 were screened to identify term babies

who at birth were SGA (<10 th

percentile). Those with major congenital anomalies, chromosomal

abnormalities, any gross neurological deficits, chronic illnesses,

prolonged hospitalization, or children whose mothers had diabetes or

gestational diabetes mellitus during the index pregnancy, were excluded

from the study. The subjects were enrolled after obtaining informed

consent from the parents. The study was approved by the institutional

ethics committee.

All enrolled children were predominantly breastfed

during first six months of life. A detailed history and clinical

examination was done in all subjects. The birthweight and length was

recorded from the hospital discharge record. Nude body weight was

recorded using an electronic weighing scale to the nearest 5 grams.

Length was recorded using an infantometer to the nearest 0.1 cm. Cohort

was segregated into symmetrical and asymmetrical SGA according to

Ponderal Index at birth. All the measurements were converted to standard

deviation scores (SDS) using WHO growth charts as reference standards.

Catch up growth was defined as gain in weight and/or length SD score of

>0.67 between birth and enrollment

[8].

A venous blood sample (1.5 mL) was taken 30 minutes

after completion of a oral glucose load (1.75 g/kg)

[5,9]. The samples were transported within two

hours of collection to the laboratory and centrifuged to separate the

serum, which was stored at –70 ºC till testing. IGF-1 levels were

measured after thawing the samples at room temperature. ACTIVE Non-

Extraction IGF-1 ELISA Kit (DSL-10-2800) was used for quantitative

measurement of IGF-1 in serum, using enzymatically amplified ‘two-step’

sandwich-type immunoassay

[9].

The difference in IGF-1 levels with respect to

catch-up growth was analyzed using Mann-Whitney U/Wilcoxon Rank sum

test. The difference in weight and length between the groups was

assessed using Kruskal-Wallis Test for variables displaying non-normal

distribution and ANOVA for normally distributed variables. A correlation

coefficient between IGF-1 levels and catch-up growth was calculated. A

probability of 5% (P<0.05) was taken as significant.

Results

A convenience sample of 50 children (54% boys) with

mean (SD) age of 15 (2.1) mo was enrolled. The mean Ponderal Index (PI)

of the study population at birth was 2.4 (0.5), suggestive of all being

symmetrical SGA. Catch-up growth was noted in 30 (60%) of the children.

CUG in both weight and length was seen in 13 (26%), length alone in 12

(24%) and only weight in 5 (10%) (Table I).

TABLE I Growth Variables in Children With Catch-up Growth and No Catch-up Growth

|

Variables |

CUG |

NCUG |

P value |

|

(n=30) |

(n=20) |

|

|

At Birth |

|

Weight (kg) |

2.0 (0.31) |

2.17 (0.29) |

0.06 |

|

Weight SDS, no (%) |

|

|

|

|

< -3 SD |

16 (53.3) |

7 (35) |

0.007 |

|

≥-3 to <-2SD |

9 (30) |

6 (30) |

|

|

≥-2 to <-1 SD |

5 (16.6) |

7 (35) |

|

|

Length (cm) (SD) |

44.3 (3.1) |

44.39 (3.3) |

1.0 |

|

Length SDS |

|

|

|

|

< -3 SD |

14 (46.6) |

8 (40) |

0.003 |

|

≥-3 to <-2SD |

5 (16.6) |

4 (20) |

|

|

≥-2 to <-1 SD |

8 (26.6) |

8 (40) |

|

|

≥-1 SD |

3 (10) |

0 |

|

|

PI (SD) |

2.2 (0.3) |

2.5 (0.6) |

0.1 |

|

At 12-18 months |

|

Weight (kg) mean (SD) |

8.1 (1.2) |

7.1 (1.1) |

0.005 |

|

Weight SDS, no (%) |

|

|

|

|

< -3 SD |

7 (23.3) |

10 (50) |

<0.001 |

|

≥-3 to <-2 SD |

5 (16.6) |

6 (30) |

|

|

≥-2 to <0 SD |

13 (43.3) |

4 (20) |

|

|

≥0 to <2SD |

5 (16.6) |

0 |

|

|

≥2 SD |

0 |

0 |

|

|

Length (cm), mean (SD) |

75.4 (5.3) |

69.3 (4.0) |

0.0 |

|

Length SDS, (%) |

|

|

|

|

< -3 SD |

7 (23.3) |

13 (65) |

<0.001 |

|

≥-3to <-2 SD |

3 (10) |

5 (25) |

|

|

≥-2 to <0SD |

12 (40) |

2 (10) |

|

|

≥0 to <2SD |

6 (20) |

0 |

|

|

≥2 SD |

2 (6.6) |

0 |

|

|

BMI (SD) |

14.4 (1.7) |

14.8 (1.7) |

0.3 |

|

CUG: Children with Catch-up growth; NCUG: Children with no CUG;

PI: Ponderal index. |

The IGF-1 in the study group followed a non-normal

distribution with a mean of 37.4 (54.4) ng/mL; ranging from 1.66 ng/mL

in the non-catch up group to 203.71 ng/mL in the catch-up group. The

mean (SD) level was significantly higher in the catch-up group [56.6

(63.2) vs 8.7 (8.3) ng/mL; P<0.001]. The mean IGF-1 levels

in those showing only weight catch-up (66.1 (73.4) ng/mL) was higher as

compared to those with only length catch-up (37.8 (52.8) ng/mL).

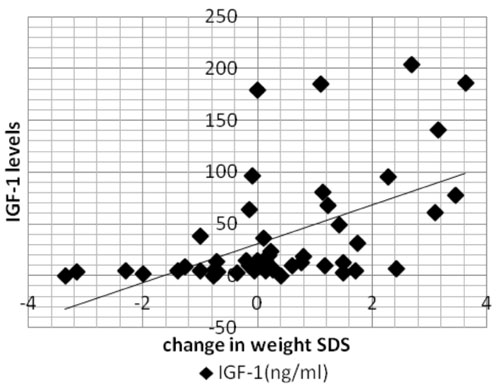

IGF-1 levels in the study cohort were found to have a

significant correlation (P<0.001) with the weight (r=0.533)

(Fig. 1), and length SDS (r=0.478, P<0.001)

change from birth.

|

|

Fig. 1 Correlation between IGF-1 and

change in weight SDS.

|

Discussion

Our data suggest that circulating levels of IGF-I in

childhood have correlation with weight-gain and height-velocity

particularly in the first two years of life. The IGF-1 levels were

significantly higher in the catch-up group than in the non-catch up

group, suggesting its role in catch-up growth. There was wide

inter-individual variation in serum IGF-I levels with skewed

distribution, which could be partially attributed to a genetic

influence. Poorer nutrition and growth may explain the greater positive

skewness of the distribution of IGF-1 concentrations in the Indian

children. This marked variation in serum concentration in first 18

months of life might limit its usefulness in assessment of growth

disorders in early life.

The strength of this study is the early age of

evaluation to detect those who do not catch-up by 18 months of age, so

that they can be closely monitored for further evaluation. The

limitation is the small size of our cohort and the results could not be

compared with AGA babies due to ethical issues.

IGF-I level of our cohort (4.85 nmol/L or 37.4 ng/L)

was less than the mean of reference population

of Low, et al. [10] at 12 months 9.7 (5.1)

nmol/L and at 18 months 13.6 (8.5) nmol/L of age. There are no Indian

studies on SGA in this age group. On comparison with the previous Indian

data [11] of healthy term babies (mean IGF-1 level at 1 year 23.1 (16.7)

ng/mL), our results were found to be similar. When compared with the

Western data (67-108 ng/mL)

[5,10,12,13], IGF-I levels were found to be lowest

in our cohort at the same age measured using the same assay, likely to

indicate delayed catch-up

[6,11,14]. As IGF-I levels are largely nutritionally regulated

[5,7,12,14], these findings are consistent with

the smaller size and chronic malnourished state of Indian children. This

may explain the lowest gain in weight and length SDS in our study group

when compared with children in other studies.

Our study concludes that majority of Indian infants

born SGA show catch-up growth as early as 12-18 months. IGF-I levels in

these are positively associated with postnatal weight and height gain,

and may potentially be used to assess growth, and correlate with

catch-up growth as early as 12-18 months of age. However, due to small

sample size, definitive conclusions are not possible.

Contributors: DR: collected the data, analyzed

and interpreted the data, wrote the paper; SY: conceptualized and

designed the study, gave critical inputs to the paper, reviewed and

approved the final manuscript; SR: data analysis, revised and reviewed

the manuscript for critical content, approved the final draft; TKM:

inputs in designing of methodology for biochemical analysis, reviewed

the final manuscript.

Funding: None; Competing interest: None

stated.

|

What This Study Adds?

• Around 60% of Indian infants born SGA show

catch-up growth by 18 months, which correlates with higher IGF-1

levels.

|

References

1. Karlberg J, Albertsson-Wikland K. Growth in

full-term small for gestational age infants: From birth to final height.

Pediatr Res. 1995;38:733-9.

2. Saenger P, Czernichow P, Hughes I, Reiter EO.

Small for gestational age: Short stature and beyond. Endocrine Rev.

2007;28:219-51.

3. Albertsson-Wikland K, Boquszewski M, Karlberg J.

Children born small-for-gestational age: postnatal growth and hormonal

status. Horm Res. 1998;49:7-13.

4. Soliman AT. Catch-up Growth: Role of GH-IGF-I Axis

and Thyroxine. In: Preedy VR, editor. Handbook of Growth and

Growth Monitoring in Health and Disease. New York: Sringer 2012. p. 8-9.

5. German I, Ong KK, Bazaes RA, Avila A, Salazar T,

Dunger D, et al. Longitudinal changes in IGF-1, Insulin

sensitivity, and secretion from birth to age three years in

small-for-gestational-age children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab.

2006;91:4645-9.

6. Mericq V, Ong KK, Bazaes RA, Pena V, Avila A,

Salazar T. Longitudinal changes in insulin sensitivity and secretion

from birth to age three years in small and appropriate-for

gestational-age children. Diabetologia. 2005;48:2609-14.

7. Chellakooty M, Juul A, Boisen KA, Damgard IN, Kai

CM, Schimdt IM, et al. A prospective study of serum insulin like

growth factor (IGF-1) and IGF binding protein-3 in 942 healthy infants:

Associations with birth weight, gender, growth velocity and breast

feeding. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:820-6.

8. Victora CG, Barros FC, Horta BL, Martorell R.

Short-term benefits of catch-up growth for small-for-gestational-age

infants. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30:1325-30.

9. Ong KK, Petry CJ, Emmett PM, Sandhu MS, Kiess W,

Hales CN, et al; ALSPAC Study Team. Insulin sensitivity and

secretion in normal children related to size at birth, postnatal growth,

and plasma Insulin like growth factor-I levels. Diabetologia.

2004;47:1064-70.

10. Low LC, Tam SY, Kwan EY, Tsang AM, Karlberg J.

Onset of significant GH dependence of serum IGF-I and IGF-binding

protein 3 concentrations in early life. Pediatr Res. 2001;50:737-42.

11. Dehiya RK, Bhartiya D, Kapadia C, Desai MP.

Insulin like growth factor-I, insulin like growth factor binding

protein-3 and acid labile subunit levels in healthy children and

adolescents residing in Mumbai suburbs. Indian Pediatr. 2000;37: 990-7.

12. Ong K, Kratzsch J, Kiess W, Dunger D; ALSPAC

Study Team. Circulating IGF-I levels in childhood are related to both

current body composition and early postnatal growth rate. J Clin

Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:1041-4.

13. Leger J, Noel M, Limal JM, Czernichow P. Growth

factors and intrauterine growth retardation. II. Serum growth hormone,

Insulin-like growth factor (IGF) I, and IGF-binding protein 3 levels in

children with intrauterine growth retardation compared with normal

control subjects: Prospective study from birth to two years of age.

Study Group of IUGR. Pediatr Res. 1996;40:101-7.

14. Soto N, Bazaes RA, Pena V, Salazar T, Avila A,

Iniguez G, et al. Insulin sensitivity and secretion are related

to catch-up growth in small-for-gestational-age infants at age 1 year:

Results from a prospective cohort. J Clin Endocrinol Metab.

2003;88:3645-50.

|

|

|

|

|