The prevalence of obesity, and its associated

metabolic disorders, is increasing dramatically in developing countries,

including India [1-3]. Although body mass index (BMI) is a simple

indicator of overweight or obesity, body fat distribution plays a major

role in cardio-metabolic health during childhood [4-7]. An increased

proportion of fat mass and a decreased proportion of fat-free mass (FFM)

during childhood have both been associated with increased risk of

developing chronic disease in later life [8]. Thus, evaluating body

composition is necessary to predict metabolic risk in childhood.

Amongst body composition assessment techniques,

Bioelectric impedance analysis (BIA) and dual-energy X-ray

absorptiometry (DXA) are the most commonly used. DXA provides acceptable

accuracy in measuring body composition among children [9]. However,

since measuring body composition using the DXA requires expertise, is

expensive, and is often not available in clinical and epidemiological

settings, the BIA is a preferred tool.

Accuracy of body composition estimation by BIA has

been evaluated in Western or Asian populations in comparison with the

DXA [10-13], but the results are inconsistent [10], presumably due to

ethnic and phenotypic differences in the study cohorts. The present

study therefore attempted to validate body composition measurements by

BIA against DXA as the reference method in healthy Indian children and

adolescents.

Methods

A random sample of 210 children (114 boys; age 5-18

y) was selected from schools in and around Pune city, India. Stratified

random sampling method was used in the selection of schools and

subjects; participants were selected gender-wise over the age range of

5-18 years. A written informed consent from the parent and an assent

from each participant were obtained. The study was approved by the

Ethics Committee of the Hirabai Cowasji Jehangir Medical Research

Institute.

Height and weight were measured with participants in

light clothes and without shoes. Standing height was measured using a

portable stadiometer (Leicester Height Meter, Child Growth Foundation,

UK) to the accuracy of 1 mm. Weight was measured using an electronic

digital scale to the nearest 0.1 kg (Salter India). Body mass index

(BMI) was calculated (Weight (kg)/Height (meter)2),

and height for age z-scores (HAZ), weight for age z-scores (WAZ), and

BMI for age z-scores (BAZ) were computed using recent Indian growth

references [14]. A pediatric endocrinologist assessed Tanner stage (TS).

Body composition was assessed by GE-Lunar DPX Pro (GE

Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA) Pencil Beam DXA scanner (software version

encore 2005, 9.30.044) to measure total %BF, total Body Fat Mass (g),

Fat free Mass (FFM) (g) and Bone mineral content (BMC) (g).

Reproducibility of DXA measurements for %BF in children was 0.47 (2.78)%

[15]. Daily quality assurance scans were run as per standard protocols.

Body composition of the subjects was also measured by

BIA (Model BC-420MA, Tanita) after at least 3 hours of fasting and

voiding before measurements, as per manufacturer’s instructions to

ensure equivalent hydration state. The Tanita Body Composition Analyzer

measures body composition using a constant current source with a high

frequency current (50 kHz, 90µA). The eight electrodes are positioned so

that electric current is supplied from the electrodes on the tips of the

toes of both feet, and voltage is measured on the heels of both feet.

BIA measures body composition as fat%, fat mass, fat-free mass, total

body water, bone-free lean tissue mass (LTM), bone mineral amount

included in the entire bone (bone mass) by measuring bioelectrical

impedance in the body. BIA measurements were tested for test-retest

reliability on a pilot sample of ten subjects separately by measuring

them on BIA at two different time points. Reliability coefficient was

significant for body fat percent, fat mass, fat free mass, lean mass

(intra class correlation coefficient = 0.99, 0.98, 0.99, 0.96,

respectively P=0.0001).

Statistical analysis: All statistical analyses

were performed using SPSS version 21.0. An independent t test was

used to determine gender differences in the participants’ physical

characteristics, DXA measure-ments and BIA measurements. P values

<0.05 were considered significant. Pearson’s correlation coefficients

between %BF, FM, FFM, LM predicted by BIA and that measured by DXA as

also with BMI were estimated. Linear regression model analysis was

performed to adjust the body composition parameters for age, BMI and TS.

Differences in body composition measurements by BIA and DXA were

examined using a paired t-test. Bland-Altman plots were used to

determine the agreement between BIA and DXA measurements [16]. The

agreement between methods is represented by the mean difference, and the

SD of the differences along with the 95% limits of agreement as the mean

difference ±1.96 SD of the differences between methods. Lin’s

concordance correlation coefficient (Rc)

was used to measure the bivariate relationship of %BF and FFM obtained

from DXA with those obtained by BIA. The degree of agreement by Lin’s

coefficient was judged by using McBride’s scale for continuous

variables; <0.90 poor, 0.90–0.95 moderate, 0.95–0.99 substantial, and

>0.99 almost perfect [17].

Results

Physical characteristics of the study cohort of 210

children and adolescents (114 boys) (mean (SD) age 11.3(2.5) yr) are

presented in Table I. Almost all (94%) children and

adolescents had normal Z scores for height, weight and BMI [14].

When compared with adult-equivalent cut-offs of BMI for Asians

corresponding to 23 and 28 kg/m2

[18], majority (78%) of the participants were in normal BMI category and

14% were overweight (Table II).

TABLE I Physical Characteristics of the Study Participants (N=210)

|

Parameter |

Age group |

|

Boys |

5-9 y |

10-13 y |

14-18 y |

|

No. |

28 |

67 |

19 |

|

Age (yr) |

8.2 (1.5) |

11.9 (1.1) |

15.2 (1.1) |

|

Weight (kg) |

24.8 (6.0) |

35.5 (9.6) |

45.2 (9.2) |

|

Height (cm) |

125.0 (10.4) |

143.7 (11.0) |

159.4 (9.3) |

|

BMI (kg/m2) |

15.6 (2.1) |

16.9 (2.7) |

17.7 (2.6) |

|

HAZ |

-0.3 (0.9) |

-0.6 (1.1) |

-0.7 (1.1) |

|

WAZ |

-0.3 (0.8) |

-0.5 (1.0) |

-0.8 (0.8) |

|

BAZ |

-0.1 (0.8) |

-0.4 (0.9) |

-0.6 (0.8) |

|

Girls |

5-9 y |

10-13 y |

14-18 y |

|

No. |

34 |

52 |

10 |

|

Age (yr) |

8.5 (1.3) |

11.9 (1.0) |

15.0 (1.3) |

|

Weight (kg) |

25.4 (6.4) |

35.2 (8.7) |

42.1 (7.8) |

|

Height (cm) |

126.8 (10.0) |

144.1 (9.2) |

148.1(5.8) |

|

BMI (kg/m2) |

15.5 (2.1) |

16.8 (2.9) |

19.1 (3.5) |

|

HAZ |

-0.2 (0.9) |

-0.4 (1.0) |

-1.1 (0.8) |

|

WAZ |

-0.2 (0.9) |

-0.6 (0.9) |

-0.8 (1.0) |

|

BAZ |

-0.2 (0.8) |

-0.5 (0.9) |

-0.3 (1.1) |

*Results are expressed as mean (SD), HAZ: Height for Age

z-score,

WAZ: weight for Age z-score, BAZ: BMI for Age z-score.

|

TABLE II Classification of Children According to BMI and Tanner Stage

|

Boys |

Girls |

All |

|

(n=114) |

(n=96) |

(N=210) |

|

Adult equivalent BMI |

Proportion of children (%) |

|

|

|

Under weight |

5.3 |

3.2 |

4.3 |

|

Normal weight |

76.1 |

80.0 |

77.9 |

|

Over weight |

15.9 |

11.6 |

13.9 |

|

Obese |

2.7 |

5.3 |

3.8 |

|

Tanner stage |

|

|

|

|

I |

45.5 |

30.5 |

38.6 |

|

II |

22.3 |

20.0 |

21.3 |

|

III |

17.0 |

14.7 |

15.9 |

|

IV |

11.6 |

12.6 |

12.1 |

|

V |

3.6 |

22.1 |

12.1 |

|

BMI: body mass index. |

TABLE III Body Composition of the Study Participants by BIA and DXA

|

Parameter |

BIA |

DXA |

|

Boys |

Girls |

Boys |

Girls |

|

Age-group:5-9 years |

(n=28) |

(n=34) |

(n=28) |

(n=34) |

|

Body fat % |

11.5 (7.2) |

16.3 (6.5) |

17.6 (7.5)** |

25.7 (11.7)**a |

|

Fat free Mass (kg)a |

21.4 (3.7) |

20.4 (4.0) |

19.6 (3.4)** |

18.2 (3.4)** |

|

Lean Mass (kg) |

20.4 (3.5) |

19.4 (3.7) |

18.8 (3.2)** |

17.3 (3.2)** |

|

Bone mineral content (kg) |

1.0 (0.2) |

1.0 (0.3) |

0.9 (0.2)** |

0.8 (0.2)** |

|

Age-group:10-13 years |

(n=67) |

(n=52) |

(n=67) |

(n=52) |

|

Body fat % |

13.2 (9.5) |

20.5 (8.9) |

21.1 (8.9)** |

27.3 (9.3)** |

|

Fat free Mass (kg) |

29.5 (5.7) |

27.9 (5.1) |

26.9 (6.1)** |

25.4 (5.2)** |

|

Lean Mass (kg) |

28.0 (5.4) |

26.4 (4.7) |

25.6 (5.8)** |

24.1 (4.9)** |

|

Bone mineral content (kg) |

1.5 (0.4) |

1.5 (0.4) |

1.3 (0.3)** |

1.3 (0.3)** |

|

Age-group: 14-18 years |

(n=19) |

(n=10) |

(n=19) |

(n=10) |

|

Body fat % |

12.9 (9.7) |

30.8 (12.2) |

21.3 (9.8)** |

35.2 (9.1)** |

|

Fat free Mass (kg) |

36.4 (7.2) |

30.4 (3.4) |

34.4 (6.5)** |

28.4 (3.4)** |

|

Lean Mass (kg) |

34.6 (6.8) |

28.8 (3.2) |

(6.2)** |

26.7 (3.0)** |

|

Bone mineral content(kg) |

1.9 (0.4) |

1.7 (0.2) |

1.6 (0.4)** |

1.7 (0.4)** |

|

Adjusted means# |

|

Adjusted Body fat % |

13.6 (7.6) |

20.0 (8.0) |

20.0 (6.7)** |

26.9 (6.8)** |

|

Adjusted Fat free Mass (kg) |

29.3 (7.6) |

26.0 (4.2) |

27.2 (7.2)** |

23.6 (4.3)** |

|

Adjusted Lean Mass (kg) |

27.9 (7.1) |

24.7 (3.9) |

26.0 (6.9)** |

22.4 (4.0)** |

|

Adjusted Bone mineral content (kg) |

1.4 (0.4) |

1.4 (0.3) |

1.2 (0.3)** |

1.2 (0.3)** |

|

Results are expressed as mean (SD); Level of Significance =

** P<0.001, a: Estimate of FFM by DXA; # means from linear

regression analysis adjusting for age, BMI and TS; BIA:

Bioelectric impedance analysis; DXA: Dual-energy X-ray

absorptiometry. |

The comparison of body composition measurements by

BIA and DXA in the study participants is shown in Table III.

The estimation of body fat% by BIA was significantly lower than the body

fat% measured by DXA in both boys and girls across all age groups (P<0.001)

(Table III). The estimates of fat-free mass, bone mineral

content and lean mass by BIA were significantly higher than by DXA (P<0.001).

These differences in estimates of FFM, BM, LM and %BF were of similar

magnitude after predicting the adjusted means for age, BMI and TS by

linear regression model (Table III). The correlations

between BMI and body composition measured on BIA were r=0.527, r=0.895,

r=0.524 and r=0.847 (P< 0.01) for FFM, FM, LM and %BF

respectively. Similarly, correlations between BMI and body composition

measured on DXA were r=0.537, r=0.885, r=0.531 and r=0.767 (P<0.01)

for FFM, FM, LM and %BF respectively. The correlations between BIA and

DXA were r=0.98, r=0.965, r=0.98, r=0.941 and r=0.917 (P<0.01)

for FFM, FM, LM, BM and %BF, respectively. The Lin’s concordance

correlation coefficients for %BF in boys and girls were low and showed a

poor agreement between DXA and BIA measurements (Rc<

0.90) (Web Table I). The FFM determined by

DXA and BIA showed a moderate agreement (Rc

between 0.90-0.95) in boys but poor agreement in girls. Similar moderate

agreement in boys and poor agreement in girls was seen for lean mass.

Bone mineral content by DXA and BIA also showed poor agreement in both

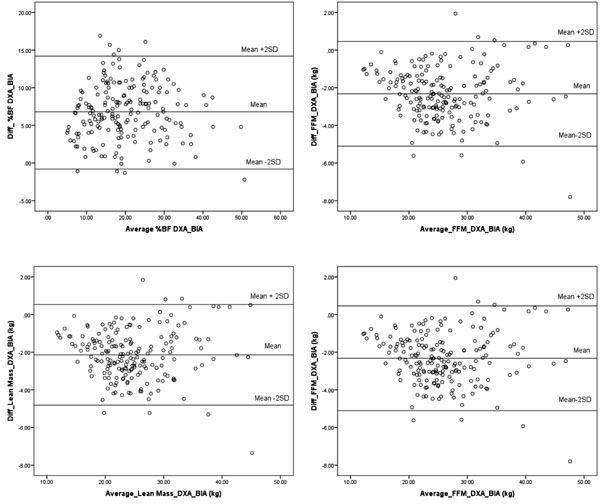

boys and girls. Overall, the mean difference between %BF by DXA and BIA

was 6.7 (3.7)%. The 95% limits for differences between the two methods

were (-0.8%, 14.2%). The width of the interval suggests that the degree

of agreement is not acceptable for using the two measurement methods

interchangeably (Fig.1a). Percentage body fat by BIA was

lower by 5.9 (3.5)% than the DXA estimate in overweight children.

|

|

Fig. 1 Comparison of BIA with DXA by Bland-Altman

plots for (a) percent body fat, (b) fat-free mass, (c) lean

mass, (d) bone mass in children and adolescents.

|

BIA overestimated lean mass than the DXA with a mean

difference of -2.15 (1.34) kg. The 95% limits of agreement between the

two methods were (-4.82 kg, 0.51 kg) (Fig. 1b). The mean

difference between DXA estimate of FFM and BIA was -2.32(1.39) kg. The

95% limits of agreement between the two methods were (-5.11 kg, 0.46 kg)

(Fig. 1c).

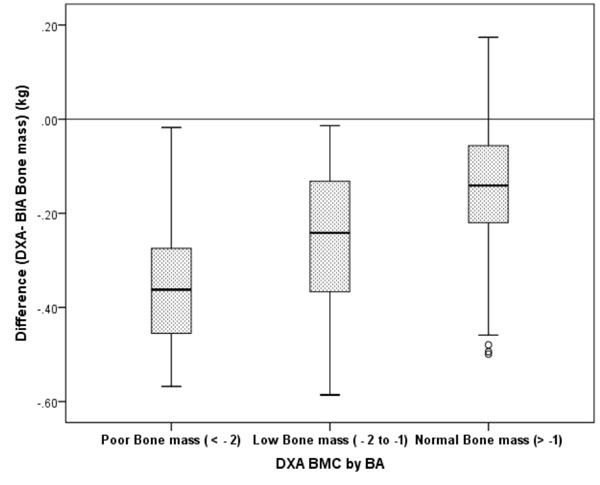

The mean difference between BMC by DXA and BIA was

-0.18 (0.15) kg. The 95% limits of agreement between the two methods

were (- 0.48kg, 0.12 kg) (Fig. 1d). The bias for BIA

estimates of BMC as compared to DXA estimates was lower in children with

normal bone mass for bone area (n = 169, -0.15 (0.14) kg), than

those with low bone mass for bone area (n = 32, -0.26 (0.15) kg)

or children with poor bone mass for bone area (n = 9, -0.34

(0.16) kg) as per DXA 85th

and 95th cut offs (14), (P<0.001)

(Fig. 2). Thus, BIA overestimated lean mass, FFM and bone

mass as compared to DXA.

|

|

BMC: Bone Mineral content; BA: Bone Area.

BMC by BA: Z score calculated using DXA measurements. Data are

presented as the mean difference ±SE. Mean difference among

three groups of BMC by BA was statistically significant (P<

0.1).

Fig. 2 Bone mineral content-dependent

bias of BIA compared with DXA in children and adolescents.

|

When children were classified as normal fat, over fat

and excess fat using DXA body fat percentile cut-offs [7] and cut-offs

for BIA by McCarthy, et al (of 85th and 95th percent body fat

percentile) [21], 93% children

were below 85th percentile for DXA cut-offs as also below

85th percentile by McCarthy, both indicating normal percent body fat.

However, 64% of excess fat children by McCarthy’s cut-offs were verfat

(between 85th and 95th percentile) or excess fat (>95th percentile) by

DXA cut-offs.

Discussion

Our findings indicate that while BIA underestimated

percentage body fat by 6.7 (3.8)% as compared to DXA measurements in

apparently healthy children and adolescents, it overestimated fat-free

mass, lean mass (muscle mass) and bone mass as compared to DXA. These

differences were of similar order after adjusting for influence of age,

BMI and Tanner stage. The accuracy and correlations between BIA and DXA

for FFM, FM, and %BF were higher than those between BMI and DXA. Even

so, both methods were similar in identifying normal fat children and

children with increased fat as per the respective available cut-offs.

One of the limitations of the present study was that

majority of the children and adolescents in the study were normal weight

children and therefore, comparison of the lean and obese children and

adolescents for the same age and gender could not be performed. However,

amongst overweight children and adolescents, underestimation of %BF by

BIA and DXA was of similar order; 5.9% in boys and 5.8% in girls.

Measurement of body composition may be performed by

several methods such as by underwater weighing, air-displacement,

dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

and computerized tomography (CT). However, either anthropometry (mainly

BMI) or BIA is a more practical method of assessing body composition in

the field setting [22]. The body mass index (BMI), although commonly

used as a surrogate measure for BF%, the relationship between BF% and

BMI is different is ethnic groups [23]. Thus, BIA maybe a more

preferable method for measuring body fat in the field setting.

An underestimation of 5% by BIA over DXA body fat%,

as we observed, is also reported in adults [12] and by 2% to 12% in

children [13,19]. The difference in percentage body fat estimates was

variable with different models of BIA devices [11] and also across body

fat ranges. A moderate agreement for FFM with different models of BIA

machines in comparison with the Hologic DXA has also been reported [11].

The underestimation by BIA may also be due to the use of

non-population-specific prediction equations by BIA models for

estimating fat and fat free mass from total body water [20].

Considering the cut-offs for body fat percentiles for

normal or excess body fat percentage [7] for the DXA and BIA (as per

85th and 95th percent body fat percentile) [21], 93% children were below

85th percentile of DXA as also below 85th percentile by McCarthy, both

indicating normal percent body fat. However, 64% of excess fat children

by McCarthy’s cut-offs were overfat (between 85th and 95th percentile)

or excess fat (>95th percentile) by DXA cut-offs. Apart from the

difference in method of assessment, this also could be because the

cut-offs for the DXA that we have used are based on Indian data while

the reference data for the BIA is based on Caucasian children. Hence,

more children were possibly classified as excess fat by the BIA cut-offs

than by the DXA cut-offs. This underlines the need for generating ethnic

specific BIA reference curves for identifying at risk children and

adolescents.

In conclusion, BIA and DXA techniques are not

interchangeable for % BF, FFM, lean mass and bone mass in children.

However, BIA may be used for the assessment of body composition in the

field/clinical setting preferably with the use of ethnic specific

references.

Contributors: SC, AK: concept and designed the

study, analyzed data and drafted the manuscript; NK: helped in data

analysis and manuscript writing; VE, LP, RM: collected data and helped

in data analysis; VK: analyzed data and manuscript writing.

Funding: Novo Nordisk India Pvt. Ltd. RM was

funded by a Fellowship Grant from the University Grants Commission

(UGC), Government of India

Competing Interest: None stated.

|

What is Already Known?

•

DXA is used to assess body

composition due to its precision although BIA is widely used in

clinical settings.

What This Study Adds?

•

BIA and DXA techniques are not interchangeable for

assessment of body composition in children.

•

BIA may be used for the assessment of body composition in

the field/clinical setting preferably with the use of ethnicity

specific references.

|

References

1. Khadilkar VV, Khadilkar AV, Cole TJ, Chiplonkar

SA, Pandit D. Overweight and obesity prevalence and body mass index

trends in Indian children. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2011;6:e216-24.

2. Deleuze Ntandou Bouzitou G, Fayomi B, Delisle H.

Child malnutrition and maternal overweight in same households in poor

urban areas of Benin. Sante. 2005;15:263-70.

3. Siervo M, Grey P, Nyan OA, Prentice AM.

Urbanization and obesity in The Gambia: a country in the early stages of

the demographic transition. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2006;60: 455-63.

4. Jahagirdar R, Hemchand KP, Chiplonkar SA,

Khadilkar VV, Khadilkar AV. Relationship between body mass index, fat

distribution and cardiometabolic risk factors in Indian children and

adolescents. Pediatr Obes. 2012;7: e37-41.

5. Artero EG, Ruiz JR, Ortega FB, Espańa-Romero V,

Vicente-Rodríguez G, Molnar D, et al. Muscular and cardio

respiratory fitness are independently associated with metabolic risk in

adolescents: the HELENA study. Pediatr Diabetes. 2011;12:704-12.

6. Steene-Johannessen J, Anderssen SA, Kolle E,

Andersen LB. Low muscle fitness is associated with metabolic risk in

youth. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41:1361-7.

7. Khadilkar AV, Sanwalka NJ, Chiplonkar SA,

Khadilkar VV, Pandit D. Body fat reference percentiles on healthy

affluent Indian children and adolescents to screen for adiposity. Int J

Obes. 2013;37:947-53.

8. Barker DJ. The developmental origins of insulin

resistance. Horm Res. 2005;64:2-7.

9. Helba M, Binkovitz LA. Pediatric body composition

analysis with dual216 energy X-ray absorptiometry. Pediatr Radiol.

2009;39:647-56.

10. Sun G, French CR, Martin GR, Younghusband B,

Green RC, Xie YG, et al. Comparison of multi-frequency

bioelectrical impedance analysis with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry

for assessment of percentage body fat in a large, healthy population. Am

J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:74-8.

11. Wang L, Hui SS, Wong SH. Validity of

bioelectrical impedance measurement in predicting fat-free mass of

Chinese children and adolescents. Med Scie Monitor. 2014;20:2298-310.

12. Li YC, Li CI, Lin WY, Liu CS, Hsu HS, Chen FN,

et al. Percentage of body fat assessment using bioelectrical

impedance analysis and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry in a weight loss

program for obese or overweight Chinese adults. PloS One. 2013;8:e58272.

13. Gutin B, Litaker M, Islam S, Manos T, Smith C,

Treiber F . Body-composition measurement in 9-11–y-old children by

dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, skinfold-thickness

measurements, and bio impedance analysis. Am J Clin Nutr.

1996;63:287-92.

14. Khadilkar V, Yadav S, Agrawal KK, Tamboli S,

Banerjee H, Cherian A, et al. Revised Indian Academy of

Pediatrics 2015 growth charts for height, weight and body mass index for

5 to 18-year-old Indian children. Indian Pediatr. 2015;52:47-55.

15. Khadilkar AV, Sanwalka NJ, Chiplonkar SA,

Khadilkar VV, Mughal MZ. Normative data and percentile curves for dual

energy X-ray absorptiometry in healthy Indian girls and boys aged 5-17

years. Bone. 2011;48:810-9

16. Bland JM, Altman DG. Measuring agreement in

method comparison studies. Stat Methods Med Res. 1999;8:135.

17. McBride GB. A Proposal for Strength-of-Agreement

Criteria for Lin’s Concordance Correlation Coefficient. NIWA Client

Report: HAM2005-062; National Institute of Water & Atmospheric Research:

Hamilton, New Zeeland, May 2005.

18. Khadilkar VV, Khadilkar AV, Borade AB, Chiplonkar

SA. Body mass index cut-offs for screening for childhood overweight and

obesity in Indian children. Indian Pediatr. 2012;49:29-34.

19. Hosking J, Metcalf BS, Jeffery AN, Voss LD,

Wilkin TJ. Validation of foot-to foot bioelectrical impedance analysis

with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry in the assessment of body

composition in young children: The Early Bird Cohort. Br J Nutr.

2006;96:1163-8.

20. Sen B, Mahalanabis D, Kurpad AV, Shaikh S, Bose

K. Total body water and fat free mass: Evaluation of equations based on

bioelectrical impedance analysis in infants and young children in India.

Br J Nutr. 2010;104:256-64.

21. McCarthy HD, Cole TJ, Fry T, Jebb SA, Prentice

AM. Body fat reference curves for children. Int J Obes. 2006;30:598-602.

22. Wang J, Thornton JC, Kolesnik S, Pierson RN Jr.

Anthropometry in body composition. An overview. Ann N Y Acad Sci.

2000;904:317-26.

23. Deurenberg-Yap M, Schmidt G, van Staveren WA,

Deurenberg P. The paradox of low body mass index and high body fat

percentage among Chinese, Malays and Indians in Singapore. Int J Obes

Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24:1011-7.