|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2012;49: 924-925

|

|

Early Presentation of Neuromyelitis Optica

|

|

Nikola Dimitrijevic, Dragana Bogicevic, *Aleksandar

Dimitrijevic and Dimitrije Nikolic

From the Department of Neurology; and *Educational

Department, University Children’s Hospital, and Medical Faculty

University of Belgrade, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia.

Correspondence to: Dr Nikola Dimitrijevic, University

Children’s Hospital, Neurology Department,

Tirsova 10, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia.

Email:

ndimitrijevic@beotel.net

Received: February 22, 2012;

Initial review: March 15, 2012;

Accepted: July 06, 2012.

|

Neuromyelitis optica is a rare autoimmune demyelinating disease of the

central nervous system in childhood. Its relapsing form is usually

reported in adults. We report a 3-year-old girl with relapsing, IgG

seropositive neuromyelitis optica. Initially she presented with optic

neuritis, followed by three relapses with deterioration of optic

neuritis and developing transverse myelitis. With each relapse, the

treatment was less effective. Four years after the onset of the disease,

the patient was blind, had paraplegia associated with urinary and bowel

incontinence and short stature.

Key words: Childhood, Neuromyelitis optica, Relapsing form.

|

|

Neuromyelitis optica is an inflammatory

demyelinating disease of the central nervous system clinicaly

presenting as optic neuritis and transverse myelitis [1,2]. The

onset ranges from early childhood to late adulthood with the mean

age in the forties. Pediatric case series data are insufficient,

especially for patients younger than six years [3,4].

Case Report

A previously healthy 3-year-old girl presented

with sudden visual loss preceded by pain while moving the left eye.

No recent history of fever, respiratory or gastro-intestinal

symptoms, infections, trauma, or vaccination was reported. The

family history was negative for neurological and autoimmune

disorders. Neurological evaluation revealed divergent strabismus,

mydriasis, and diminished pupillary reflex of the left eye.

Fundoscopy showed left optic disc pallor. Visual evoked potentials

were absent on the left eye, and significantly prolonged with

diminished amplitudes on the right eye. Brain MRI revealed slight

enlargement of the optic nerves, pre-dominantly on the left side.

Complete blood count and biochemical testing was normal. Analysis of

the cerebrospinal fluid showed normal findings with absent

oligoclonal bands. Serological tests for Toxoplasma, Borrellia

burgdorferi, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Herpes simplex virus,

Epstein-Bar virus, cytomegalovirus, adenoviruses, influenza A and B

viruses, varicella zoster virus and HIV were negative. Antinuclear,

antiphos-pholipid and anti-thyroid antibodies, LE cells and

rheumatoid factor were negative. Levels of complement were within

normal ranges. The patient was treated with intravenous

methylprednisolone 20 mg/kg/day for 5 consecutive days, followed by

oral prednisone. Clinical improvement was noticed 2 weeks later with

visual function recovery on visual evoked potentials (complete on

the right and partial on the left eye).

The first relapse occurred 17 months later. The

patient developed flaccid paraparesis with increased tendon reflexes

and loss of sphincter control, preceded by back pain. This was

followed by bilateral loss of vision in the next five days. Brain

MRI was normal. Spine MRI showed a signal increase in spinal cord

between T8 and T12 levels on T2–weighted images. Intravenous

methylprednisolone therapy was repeated. Ten days after the

initiation of the steroid therapy the patient regained vision of the

right eye, with improved muscle strength and nearly normal muscle

tone of lower extremities. A month later sphincter control was

established. Spinal cord lesion on the control MRI disappeared

completely.

|

|

(a)

(b)

(c)

|

|

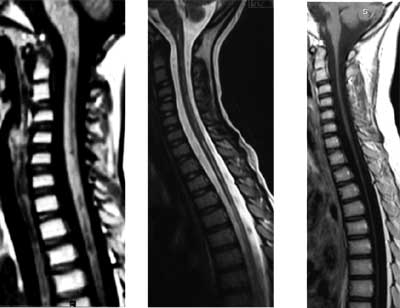

Fig. 1 Progression of spinal cord

atrophy shown on MRI (a) at the second relapse; (b) at the

third relapse; and (c) after third relapse.

|

Second relapse occurred at the age of 5 years and

10 months, with loss of vision in the right eye and weakness in the

arms and legs. There was moderate hypertonia in legs with Babinski

sign and increased tendon reflexes. Visual evoked potentials showed

no cortical responses. Brain MRI was normal. Spine MRI revealed

enhanced signal on T2 weighted images between C1 and T2 levels (Fig.

1a). Intravenous methylprednisolone was administered, with

significant improvement after two weeks. Patient was able to walk,

climb the stairs and jump. Muscle tone of the arms and legs was

normalized, but the left eye blindness persisted.

The third relapse occurred at the age of 6 years

and 4 months with total loss of vision and inability to sit, stand

and walk. Vibratory sensory loss was noted below T10 level. Brain

MRI showed atrophy of both optic nerves, optic chiasm and optic

tracts . Spine MRI revealed diffuse cervical and thoracic spinal

cord atrophy with subsequent dilatation of the central canal (hydromyelia)

(Fig. 1b). Intravenous methylprednisolone and

immunoglobulin treatement was unsuccessful. Parents of the patient

refused any further therapy.

An year later, neuromyelitis optica testing

revealed high titer of antibodies.

At the age of nine years the patient was blind

with spastic paraparesis, sensory loss below T10 level, urinary and

bowel incontinence, neurogenic bladder with recurrent urinary

infections, and height below third percentile. Mental development

was normal. MRI revealed severe atrophy of the spinal cord (Fig.

1c).

Discussion

Relapsing neuromyelitis optica is rare in

children. The youngest case previously reported in literature was a

boy of 23 months [3]. Our patient presented with isolated optic

neuritis at the age of 3 years, transverse myelitis occurred 17

months later. At the time of the first relapse, our patient

fulfilled all absolute criteria, two out of three major supportive

criteria and all minor supportive criteria for the diagnosis of

neuromyelitis optica. NMO-IgG antibodies were confirmed later [5-7].

The diagnosis of neuromyelitis optica has been

considerably facilitated by the discovery of highly specific serum

autoantibody biomarker - NMO-IgG [6]. The high titer of NMO-IgG

correlates well with frequent relapses [8]. Patients with the

relapsing form of NMO have demonstrated progressive disability.

There are no scientifically proven guidelines and

treatment strategies either in the acute attacks or on a long-term

base. The outcome depends on early effective immunosuppression prior

to accumulation of severe neurological damage.

Our patient is one of the youngest cases with

relapsing NMO and NMO-IgG seropositivity reported in the literature.

Although rare, pediatric NMO needs specific attention due to an

unpredictable clinical course and possible poor outcome with severe

disability . It is very important to identify risk factors that

predict a relapsing course and to determine optimal treatment,

especially for long-term preventive immunotherapy.

Acknowledgments: Professor Robert Marignier

and Laboratory in Bron (France) for performing NMO-IgG analysis.

Professor Borivoj Marjanovic from Insitute for Mother and Child,

Belgrade, for useful clinical suggestions.

References

1. Wingerchuk DM, Weinshenker BG. Neuromyelitis

optica. Curr Treatment Options Neurol. 2008;10:55-66.

2. Weinshenker BG. Neuromyelitis optica is a

distinct from multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2007;64:899-901.

3. Yuksel D, Senbil N, Yilmaz D, Yavuz Gurer YK.

Devic’s neuromyelitis optica in an infant. J Child Neurol.

2007;22:1143.

4. Loma IP, Asato MR, Filipink RA, Alper G.

Neuromyelitis optica in young child with positive serum

autoantibody. Pediatr Neurol. 2008;39:209-12.

5. Wingerchuk DM, Lennon VA, Pittock SJ,

Lucchinetti CF, Weinshenker BG. Revised diagnostic criteria for

neuromyelitis optica. Neurology. 2006;66: 1485-9.

6. Lennon VA, Wingerchuk DM, Kryzer TJ, Pittock

SJ, Lucchinetti CF, Fujihara K, et al. A serum autoantibody

marker of neuromyelitis optica: distinction from multiple sclerosis.

Lancet. 2004;364:2106-12.

7. Krupp LB, Banwell B, Tenembaum S. Consensus

definitions proposed for pediatric multiple sclerosis and related

disorders. Neurology. 2007;68:S7-12.

8. Banwell B, Tenembaum S, Lennon VA, Ursell E,

Kennedy J, Bar-Or A, et al. Neuromyelitis optica-IgG in

childhood inflammatory demyelinating CNS disordes. Neurology.

2008;70:344-52.

|

|

|

|

|