Formative assessment has a major influence on

learning [1]. The educational utility of a summative or year-end

examination is limited since it usually involves a single encounter

with assessment of a limited number of competencies, mostly

knowledge-based, with no opportunity for feedback and improvement.

Internal assessment provides a very useful opportunity to not only

test acquisition of knowledge but also provide feedback to make

learning better.

The strengths of internal assessment (IA) are

three-fold. One, there is an opportunity to provide timely

corrective feedback to students. Feedback is recognized as the

single-most effective tool to promote learning [2].Two, IA can be

designed to test a range of competencies, such as, skill in

performing routine clinical procedures (giving injections, suturing

wounds, performing intubation etc.), professionalism, ethics,

communication, and interpersonal skills, which are hardly assessed

in the final examinations [3]. Three, the continuous nature of this

assessment throughout the training period has the potential to steer

the students’ learning in the desired direction over time. The focus

is on the process, as much as on the final product of learning.

The concept of IA is not new. The University

Grants Commission [4] recommends that we need to "… move to a system

which emphasizes continuous internal assessment and reduces

dependence on external examinations to a reasonable extent."

Similarly, the National Accreditation and Assessment Council (NAAC)

encourages the use of internal assessment to guide learning [5].

The draft of the 2012 revised Regulations on

Graduate Medical Education (GME) released by the Medical Council of

India (MCI) stipulates that undergraduate students should have

passed in their IA to be eligible to appear in the final university

examinations [6]. The recommendation is for IA to be based on

day-to-day records. Also, regular assessments conducted throughout

the course shall relate to assignments, preparation for seminars,

clinical case presentations, participation in community health care,

proficiency and skills required for small research projects etc.

Further, electives and skills should be assessed as part of internal

assessment [6].

Problems with Internal Assessment in India

Despite its obvious strengths, internal

assessment has not been used to its full potential in India. Often

trivialized as a replica of the final examination, IA is restricted

only to theory and practical tests, while its potential to test

other competencies is seldom exploited. The major issues with

internal assessment in India are: improper implementation, lack of

faculty training, misuse or abuse, lack of acceptability among all

stakeholders and perceived lack of reliability [7].

Improper implementations: Implementation has

a strong bearing on any assessment and its educational utility. The

earlier 1997 guidelines [8] did not carry any mention of how the IA

was to be implemented. Institutions were left to design their own

plan of IA leading to considerable variation in the methods of

assessment and the competencies assessed. Practical guidelines have

not been provided for implementation of IA in the 2012 revised

regulations on GME [6] either, giving rise to a sense of déjà vu.

Lack of faculty training: Faculty

development is pre-requisite to proper implementation of any

educational method. Lack of training is often the reason for poor

implementation, lack of transparency, and inadequate or no provision

of feedback to students. By not providing timely and appropriate

feedback, the biggest strength of internal assessment is nullified.

When teachers do not give competencies such as communication skills,

professionalism, ethics, interpersonal skills, ability to work in a

team etc. enough weightage in the internal assessment due to the

fear that these cannot be precisely measured, they indirectly convey

to students that these qualities are not important in medicine.

While the faculty do gain experience of teaching and research, there

is no opportunity for them to get a hands-on experience on student

assessment.

Misuse/Abuse: IA is often misused as

an examination without external controls [9-10].The 2012 draft

regulations [6] have proposed some variations from the 1997

regulations [8]. Marks of IA are no longer to be added to the final

scores. Although not expressly stated, fear of abuse of IA to

inflate marks seems to have prompted this change. However, this

opens new opportunities to use IA to assess competencies hitherto

left un-assessed.

Lack of acceptability: The issues that

lower the acceptability of IA from all its stakeholders are:

variability in marking by institutions, too much ‘power’ bestowed to

single individuals (often departmental heads), too much weightage to

single tests and a perceived lack of reliability. Reliability (also

sometimes described as reproducibility) is commonly seen as

‘consistency of marking’. Here, it may be pertinent to clarify that

reliability should be seen as consistency or reproducibility of

student performance rather than consistency of marking by examiners.

Assessing a student in one clinical situation poorly predicts his

performance in another clinical situation. Also, it is uncertain

that a physician will encounter the same conditions in actual

practice under which he was assessed. Therefore, if reliability has

to contribute towards prediction of student’s future performance in

real situations, the true meaning of reliability should be

‘consistency of performance’ rather than ‘consistency of scoring’

[11]. Marker variability in IA is often cited as a reason for lack

of reliability. Research has consistently shown that increasing the

number of assessors and increasing the sample of the content being

assessed improves reliability [12]. Even with rather subjective

assessments, having different assessors for different parts of a

test can neutralize an incompetent/ biased assessor’s influence

[13]. By increasing the number of clinical situations in which a

student is assessed, the reliability of the assessment can be

improved more than by merely making more objective tests.

The utility of any assessment is dependent upon

its validity, reliability, acceptability, feasibility and

educational impact [14]. Although each one of these attributes is

important, there is always some trade-off between them. For example,

an assessment which is apparently low on reliability can still be

useful by virtue for its positive educational impact [13]. Where

combinations of different assessments alleviate draw-backs of

individual methods, use of the programmatic approach to assessment

is advocated, thereby rendering the total more than the sum of its

parts [15].

When properly implemented, IA scores over the

year-end examination in terms of its validity, reliability

(consistency of performance), feasibility and educational impact

[7]. To ensure that students are not denied the benefit of this

extremely useful modality, efforts need to be made to improve its

implementation and acceptability.

In this paper, we propose a model for internal

assessment, which tries to overcome some of the issues that teachers

and students face. We call it the ‘in-training assessment

(ITA) program’ as it reflects the philosophy and intent of

this assessment better. The ITA is designed to not only test

knowledge and skills, but also provide an opportunity to assess

competencies which are not assessable by conventional year-end

examinations. The purpose of ITA is to provide feedback to students

and teachers, and to improve student learning. It is proposed to be

a longitudinal program spread throughout the MBBS training. ITA is

expected to be complementary to the end-of-training assessment (ETA)

carried out by the affiliating Universities to test for attainment

of intended competencies.

The Proposed Quarter Model

The salient features of this model are outlined

in the Box 1.

|

Box 1: The Quarter Model of

In-training Assessment

1. One assessment to be conducted at

least every quarter.

2. No teacher to contribute more than a

quarter (25%) of the marks for any student.

3. No single tool to contribute more than

a quarter (25%) of the marks.

4. No single assessment to contribute

more than a quarter (25%) of the total marks.

|

Format: We propose that students be

periodically assessed during the course of their training by the

faculty of their parent institutes. Passing separately in ITA and

ETA, in both theory and practical/clinical components should be

mandatory. As proposed in the Graduate Medical Education Regulations

2012 [6], while passing in ITA will be an eligibility criterion for

appearing in the University examinations, marks obtained in ITA will

not be added to the marks obtained in ETA. The scores can be

converted to grades using a 7-point scale (using absolute grading

criteria) and shown separately on the mark-sheet issued by

Universities.

Organization and Conduct: To allow

greater spread of marks, each subject may be assessed out of a

maximum of 100 marks (50% for theory and 50% for practical/clinical

component) in the ITA. ITA should make use of a number of assessment

tools. For theory: essay questions, short answer questions (SAQ),

multiple choice questions (MCQ), extended matching questions and

oral examinations should be used. For practical/clinical assessment:

experiments, long cases, short cases, spots, objective structured

practical/clinical examinations (OSPE/OSCE), mini-clinical

evaluation exercise (mini-CEX) and objective structured long

examination record (OSLER) should be used. Viva in

practical/clinical assessment should focus on the experiments

actually performed or cases actually seen rather than being a

general viva. Colleges can add more tools depending on the local

expertise available.

The planning and assessment for ITA should

involve all teachers of each department to ensure that no single

teacher contributes more than 25% of the marks to the total marks

and no single assessment tool contributes more than 25% marks to the

total ITA. For this purpose, teachers would mean all those working

as tutors/ senior residents and upwards.

The proportion of 25% marks should be calculated

from the assessments spread over the entire year. For example, the

departments should be at liberty to have four assessments with one

having only essay type questions, another having only MCQs, the

third having only oral examination and a fourth one with a mix of

all. Or they could have four assessments with a mix of essays, SAQs,

MCQs and oral examinations. The same applies to practical/clinical

examinations. However, for subjects like radiology, TB and chest,

dermatology, casualty and dentistry, each teacher and each tool may

contribute 50% to the assessment in that subject. In effect, it

means that to maintain the 25% limit, at least four teachers and

four different assessment tools should be used for ITA. For subjects

with the 50% limit, at least two teachers and two tools will be

required.

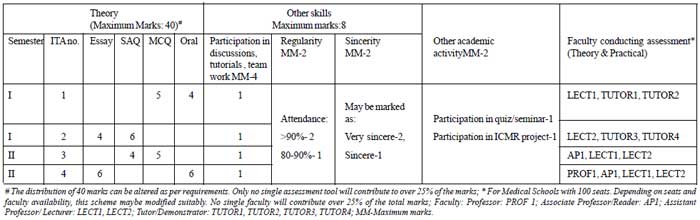

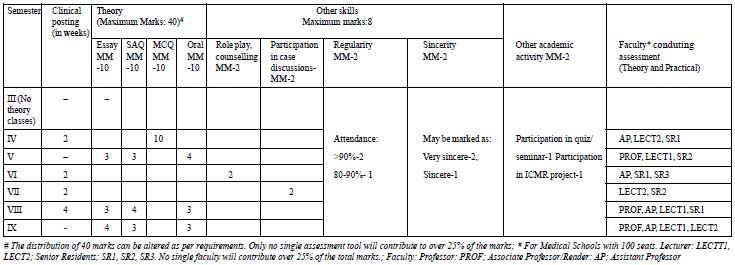

The marks for ITA in each subject is shown in

Table I. To illustrate its working, two examples, one

from a pre-clinical (Physiology) and another from a clinical

(Pediatrics) department are provided (Fig. 1 and 2).

TABLE I Division of Marks

|

Theory (Max. marks 50) |

|

Practical/clinical (Max. marks 50) |

|

|

Knowledge tests: using multiple tools* |

40 |

Practical and clinical skills (including communication |

35 |

|

|

skills, bedside manners): using multiple tools*

|

|

|

Preparation, participation, regularity, sincerity |

8 |

Regularity, sincerity, professionalism, presentation |

8 |

|

Other academic activities: quiz, seminar etc. |

2 |

Log books |

5 |

|

|

ICMR or other projects, community work, etc. |

2 |

The given sample formats have been drafted using

the prescribed number of teaching staff for an institution admitting

a batch of 100 students in a year. Utilization of end-of-posting

assessment for the practical component of ITA in clinical subjects

may contribute towards time efficiency of the ITA program by using

same assessments for formative as well as summative purposes.

|

|

Fig.1 Physiology : Sample format for ITA.

|

As Fig.2 shows, ITA is

proportionately divided over the phases for subjects that are taught

over different semesters. For subjects that include other allied

subjects (e.g. Medicine includes Dermatology, Psychiatry

etc.), a proportion of ITA is allocated to allied subjects based on

the teaching time allotted. Students would need to secure passing

marks (>50%) in theory and practical separately for allied subjects

also.

|

|

Fig 2 Pediatrics: Sample format for ITA - Theory

(maximum mark 50); Minimum 4 ITAs over entire course.

|

All results should be declared within two weeks

of the assessment. Students should sign on the result sheet in token

of having seen the results. The results should also be uploaded on

the college website within two weeks of being put up on the notice

board. Students who do not pass in any of the assessments should

have the opportunity to appear for it again – however, any repeat

assessment should not be conducted earlier than two weeks of the

last to allow students to meaningfully make good their deficiencies.

Only one additional assessment may be provided to make good the

deficiency. If a student is unable to score 50% even after an

additional assessment, he should repeat the course/posting and

appear for University examinations 6 months later.

Teachers should provide feedback to students

regarding their performance. A group feedback session should be

organized within a week after declaration of results. However, for

persistently low achieving students, one-to-one feedback sessions

may be organized.

To use the power of assessment meaningfully for

better learning and to ensure stability in assessments, all colleges

should appoint a Chief Coordinator. All the teaching departments

should also appoint a teacher as coordinator to plan and organize

ITA. Departments should coordinate among themselves and with the

Chief Coordinator to ensure that students do not have assessment in

more than one subject during the same week. As far as possible, all

ITAs should be scheduled on Monday mornings so that students get the

weekend to prepare and do not miss classes. For clinical subjects,

the practical component of the ITAs should be scheduled at the end

of clinical postings. The minimum number of ITAs for each subject

should be specified in the beginning of the term. The plan and

tentative dates of assessment should be put up on the notice board

within the first month of starting that phase of training. The ITA

plan of each department should be developed as a standard operating

protocol (SOP) document, approved by the Curriculum/ Assessment

committee of the college and reviewed (and revised if required)

annually. This document should be made available to the students at

the beginning of each phase.

Record keeping: It is important to

maintain a good record of performance in ITA to ensure credibility.

Students should have access to this record and should sign it every

three months. A sample format for record keeping has previously been

published [16].

Faculty development: Unless both the

assessors and students understand the purpose of this exercise, this

powerful tool will continue to be trivialized and acceptance will

remain suboptimal. Success of this model will require training

faculty in use of multiple assessment tools. Currently, faculty

development is carried out through the basic course workshops on

medical education; this needs to be scaled up for capacity building

of medical teachers. It is also imperative that the students be

sensitized to the ITA program for MBBS during the proposed

foundation course (the first two months before Phase I of MBBS).

Discussion

The quarter model addresses several commonly

leveled criticisms against internal assessment. The strength of ITA

is expected to be realistic in its continuous nature and in the fact

that it is based on longitudinal observations in authentic settings.

Provision of feedback not only allows for mid-course correction of

the learner’s trajectory [17] but also reinforces their strong

points.

Medical competence is an integrated whole and not

the sum of separate entities. No single instrument will ever be able

to provide all the information for a comprehensive evaluation of

competence [18]. Single assessments, howsoever well planned, are

flawed [15]. By including assessment in various settings and by use

of multiple tools in this model, the intention is to increase the

sampling and to make more well-informed and defensible judgments of

students’ abilities. Use of multiple examiners is expected to help

reduce the examiner biases involved in the process of assessment,

and also minimize misuse of power.

Understandably, this model may demand more effort

and work from the faculty members. However, we feel that that the

added benefits of this model would be a better distribution of

student assessment tasks within the department and also an

opportunity for the tutors/senior residents to be trained in

assessment methods under supervision. It must be reiterated here

that assessment requires as much preparation, planning, patience and

effort that research or teaching does. Assessment has been taken

rather casually for far too long and at least semi-prescriptive

models of ITA based on educational principles are a need of the day.

Ignoring educational principles while assessing students, merely

because it results in more work, seriously compromises the utility

and sanctity of assessment.

Black and Wiliam [19] state that any strategy to

improve learning through formative assessment should include: clear

goals, design of appropriate learning and assessment tasks,

communication of assessment criteria and provision of good quality

feedback. Students must be able to assess their progress towards

their learning goals [17]. The quarter model largely takes into

account all these elements. Our model gives a broad overview of what

is and what is not being measured. It also balances the content and

counteracts the tendency to measure only those elements which are

easy to measure. By involving students early in the process,

informing them of the criteria by which they will be judged, the

assessment schedules and most importantly, giving them feedback on

their learning, the model is expected to provide them an opportunity

to improve performance. The display of ITA grades alongside the ETA

marks is expected to demonstrate the consistency of student

performance and prevent manipulation of marks.

This model has been conceptualized using accepted

theories of learning and assessment. Multiple tests on multiple

content areas by multiple examiners using multiple tools in multiple

settings in the quarter model will improve the reliability and

validity of internal assessment, and thereby improve its

acceptability among all stakeholders.

1. Rushton A. Formative assessment: a key to deep

learning. Med Teacher. 2005; 27:509-13.

2. Hattie JA. Identifying the salient facets of a

model of student learning: A synthesis of meta-analyses. Int J Educ

Res. 1987;11:187–212.

3. Singh T, Natu MV. Examination reforms at the

grassroots: Teacher as the change agent. Indian Pediatr.

1997;34:1015-9.

4. University Grants Commission. Action Plan for

Academic and Administrative Reforms. New Delhi. Available from:

URL:http://ugc.ac.in/policy/cmlette2302r09.pdf. Accessed 24 June,

2012.

5. National Accreditation and Assessment Council.

Best Practice Series-6. Curricular Aspects. Available from: URL:

http://naac.gov.in/sites/naac.gov.in/files/Best%20

Practises%20in%20Curricular%20Aspects.pdf. Accessed 24 June, 2012.

6. Medical Council of India Regulations on

Graduate Medical Education 2012. Available from: URL:

http://www.mciindia.org/tools/announcement/Revised_ GME_2012.pdf.

Accessed 24 June, 2012.

7. Singh T, Anshu. Internal assessment revisited.

Natl Med J India. 2009;22:82-4.

8. Medical Council of India Regulations on

Graduate Medical Education 1997. Available from: URL:

http://www.mciindia.org/RulesandRegulations/Graduate

MedicalEducationRegulations1997.aspx. Accessed 24 June, 2012.

9. Gitanjali B. Academic dishonesty in Indian

medical colleges. J Postgrad Med. 2004;50:281-4.

10. RGUHS does it again, alters MBBS marks.

Available from: URL:

http://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2006-04-25/bangalore/27804396_1_internal-assessment-rguhs-medical-colleges.

Accessed 24 June, 2012.

11. Feldt LS, Brennan RL. Reliability. In:

Linn Rl, editor. Educational Measurement. 3rd edn. New York:

Macmillan; 1989.p. 105-46.

12. van der Vleuten CPM, Scherpbier AJJA, Dolmans

DHJM, Schuwirth LWT, Verwijnen GM, Wolfhagen HAP. Clerkship

assessment assessed. Med Teacher. 2000;22:592-600.

13. van der Vleuten CPM, Norman GR, De Graaff E.

Pitfalls in the pursuit of objectivity: Issues of reliability.

Medical Education. 1991;25:110-8.

14. van der Vleuten CPM, Schuwirth LWT. Assessing

professional competence: from methods to programmes. Medical

Education. 2005;39:309-17.

15. van der Vleuten CPM, Schuwirth LWT, Driessem

EW, Dijkstra J, Tigelaar D, Baartman LKJ, et al. A model for

programmatic assessment fit for purpose. Medical Teacher.

2012;34:205-14.

16. Singh T, Gupta P, Singh D. Continuous

internal assessment. In: Principles of Medical Education. 3rd

edn. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers; 2009. p.107-12.

17. Burdick WP. Foreword. In: Singh T,

Anshu, editors. Principles of Assessment in Medical Education. 1st

edn, New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers; 2012.

18. Dijkstra J, van der Vleuten CPM, Schuwirth

LWT. A new framework for designing programmes of assessment. Adv

Health Sci Educ. 2010;15;379-93.

19. Black P, Wiliam D. Assessment and classroom learning.

Assessment in Education.1998;5:7-75.