|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2010;47: 945-953 |

|

Gallstone Disease in Children |

|

Ujjal Poddar

Correspondence to: Dr Ujjal Poddar, Department of

Pediatric Gastroenterology, Sanjay Gandhi Post Graduate

Institute of Medical Sciences, Raebareli Road, Lucknow 226 014, Uttar

Pradesh, India.

Email: [email protected]

|

Context: Little is known about the epidemiology of cholelithiasis

in children. Cholelithiasis and choledocholithiasis were considered to be

uncommon in infants and children but have been increasingly diagnosed in

recent years due to wide- spread use of ultrasonography. However, there is

not much of information from India and no consensus among Indian

pediatricians and pediatric surgeons regarding management of gallstones in

children. Hence, the purpose of this review is to increase awareness about

the management of gallstones in children. Methods: Extensive

electronic (PubMed) literature search was made for this purpose and

literature (original articles, clinical trials, case series, review

articles) related to gallstones in children were reviewed. Conclusions:

The etiologies of cholelithiasis are hemolytic (20%-30%), other known

etiology (40%-50%) such as total parenteral nutrition, ileal disease,

congenital biliary diseases, and idiopathic (30-40 %). Spontaneous

resolution of gallstones is frequent in infants and hence a period of

observation is recommended even for choledocholithiasis. Children with

gallstones can present with typical biliary symptoms (50%), nonspecific

symptoms (25%), be asymptomatic (20%) or complicated (5%-10%).

Cholecystectomy is useful in children with typical biliary symptoms but is

not recommended in those with non-specific symptoms. Prophylactic

cholecystectomy is recommended in children with hemolytic disorders.

Key words: Choledocholithiasis, Cholelithiasis, Outcome.

|

|

Cholelithiasis

or gallstones are quite common in adults. The prevalence of gallstones

among adult population in the West is 10% to 20% (1,2) and this figure in

India is 3% to 6%(3,4). Interestingly the prevalence of gallstones is

seven times more frequent in north India than in south India(5) and the

composition of gallstones is also different in different parts India. In

north and eastern India, gallstones are predominantly cholesterol stones

and mixed stones; on the other hand, in south India, pigment stones are

predominant(6,7). The natural history of gallstones in adults has shown

that the majority (more than 80%) are incidentally detected asymptomatic

gallstones(8) and the majority of them (>80%) remains asymptomatic on long

term follow up; even if they develop complications (like pancreatitis,

cholecystitis, choledocholithiasis), they are usually preceded by biliary

colic(1,9). Hence, in adults, prophylactic cholecystectomy is not recommended

for asymptomatic gallstones. However, the picture is not so clear in

children.

Gallstones were considered to be uncommon in infants

and children but have been increasingly diagnosed in the recent years,

mainly due to wide spread use of ultrasonography. There is not much

information about cholelithiasis in children from India and there is no

consensus among Indian pediatricians and pediatric surgeons regarding the

management of gallstones in children. Hence, the purpose of this review is

to increase awareness about the management of gallstones in children.

Methods

A detailed electronic (PubMed) literature search was

made for this purpose and English language literature (original articles,

clinical trials, case series, case report, letter, meta-analysis, practice

guideline, randomized controlled trial) related to gallstones in children

(key words used: gallstones, children, ceftriaxone, fetal gallstones) were

reviewed. The period of search was from 1965 to December 2009. During this

period a total of 372 articles were published of which relevant 61

articles were included in this review.

Epidemiology

Little is known about the epidemiology of

choleli-thiasis in children. Cholelithiasis and choledo-cholithiasis have

been increasingly diagnosed in recent years in children. This phenomenon

may be attributed to better medical imaging (especially ultrasonography)

and its usage in investigating children with unexplained abdominal pain

and/or a genuine increase in the incidence of cholelithiasis due to

increasing use of total parenteral nutrition, frusemide and phototherapy

in the infants(10). The exact prevalence of gallstones in children is not

known. Studies from Europe have shown an overall prevalence of gallstone

disease of 0.13% to 0.2% in children(11,12).

In Japan, the prevalence of gallstone disease is reported to be less than

0.13% of children(13). The only report from India by Ganesh, et al.

has shown a prevalence of 0.3% in a hospital based observation among

13,675 children(14). However, the prevalence of gallstones among obese

children and adolescents was shown to be quite high (2% of 493 children)

in a recent study(15). Studies on cholelithiasis in children have shown a

bimodal distribution, with a small peak in infancy and a steadily rising

incidence from early adolescence onwards(11,16). Boys and girls are

equally affected in early childhood, but as in adults, a clear female

preponderance emerges during adolescence.

A unique subset is chronic hemolytic disease. In this

condition, cholelithiasis is usually not seen before the age of five and

thereafter, the incidence increases progressively with age. In sickle-cell

disease, the prevalence of pigment gallstones was reported to be 10% to

15% in children under 10 years of age, it increased to 40% in those aged

10-18 years, and 50% in adults(17-19). The prevalence of gallstones in

hereditary spherocytosis was 10% to 20% and in adult series it was

40%(20,21). In thalassemia, the reported figure is low (10% to

15%)(22,23). With longer survival of thalassemia patients, higher

prevalence of gallstones (50%) has been reported(24). The highest

prevalence of gallstones have been reported in thalassemics with Gilbert’s

syndrome genotype(24,25). However, in a study on 64 patients with median

age of 10 (range, 5 to 20) years with thalassemia major from Chandigarh,

none had gallstones(26).

Pathogenesis

Gallstones are either cholesterol gallstones (pure and

mixed) or pigment stones (black or brown). Cholesterol supersaturation of

bile with stasis predisposes to cholesterol gallstone formation. Mixed

cholesterol gallstones are the commonest stones in adults and in

adolescent girls. However, pigment stones are more common in children.

Black pigment stones are formed due to supersaturation of bile with

calcium bilirubinate and are seen in hemolytic disorders and in

association with total parenteral nutrition. Brown pigment stones are

associated with infection and biliary stasis and form more often in the

bile ducts than in the gallbladder(16).

Biliary sludge is composed of mucin, calcium

bilirubinate and cholesterol crystals. It is commonly associated with

prolonged fasting, total parenteral nutrition, pregnancy, sickle-cell

disease, treatment with ceftriaxone or octreotide(27). The natural history

of biliary sludge is variable; it may resolve spontaneously or may

progress to gallstone develop-ment. Persistent sludge may give rise to

biliary complications (such as obstruction or infection).

Etiologically cholelithiasis (Table I)(11,16)

in children can be divided into three groups; hemolytic, other known

etiology, and idiopathic. Almost 20% to 30% of all gallstones in children

are due to hemolytic diseases such as sickle-cell disease, hereditary

spherocytosis and thalassemia. In around 40% to 50% of cases, gallstones

are due to another known etiology such as total parenteral nutrition,

prolonged fasting, ileal disease or ileal resection, frusemide therapy,

congenital biliary diseases such as choledochal cyst, chronic liver

disease and progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis (PFIC). Around

30% to 40% of cases are idiopathic. As in adults, gallstones in adolescent

girls are more often idiopathic(16).

TABLE I

Etiology of Gallstones in Children(11,16)

|

Type of gallstones |

Proportion of all gallstones

in children |

Etiology |

|

Hemolytic |

20%-30% |

Sickle-cell disease, hereditary spherocytosis, thalassemia major |

|

Non-hemolytic |

40%-50% |

TPN, prolonged fasting, ileal disease (like Crohn’s disease) or

resection, prematurity, frusemide therapy, cardiopulmonary bypass,

congenital biliary malformations, PFIC, chronic liver disease,

cystic fibrosis, OCP, teenage pregnancy |

|

Idiopathic |

30-40% |

No predisposing factor |

|

TPN: total parenteral nutrition, PFIC:

progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis, OCP: oral

contraceptive pills |

Total parenteral nutrition and cholelithiasis

Total parenteral nutrition (TPN) impairs entero-hepatic

circulation and cholecystokinin induced gallbladder contraction resulting

in biliary stasis, sludge and stones(28). The longer the duration of TPN

therapy, the higher the risk of developing cholelithiasis(29). The risk of

developing gallstones in children on prolonged TPN therapy is increased if

there is concomitant ileal resection or disease. In a study of 21 children

on prolonged TPN (more than 3 months), Roslyn, et al. have shown

that 43% of children developed gallstones but this figure was 64% in

children with ileal resection or disease(29). Sludge develops more rapidly

in neonates than in adults after a mean time of TPN infusion in neonates

of 10 days, as compared with more than 6 weeks in adults. In a prospective

study of 41 neonates, Matos, et al. have shown that gallbladder

sludge appeared in 18 (44%) of those infants who had received TPN infusion

for a mean period of 10 days(30). In 12 infants, the sludge cleared within

one week of resuming enteral feeding but two of the remaining infants went

on to develop asymptomatic gallstones. Spontaneous resolution occurred in

one of these two infants by 6 months while the calculi persisted in the

other baby.

Ceftriaxone-associated biliary pseudolithiasis

Ceftriaxone, a third-generation cephalosporin, is a

popular drug among pediatricians as it has a broad spectrum of

antimicrobial activity and good CSF penetration. Biliary sludge or biliary

lithiasis has been reported as a potential complication of ceftri-axone

treatment since 1986(31). Since ceftriaxone induced biliary lithiasis is

reversible and disappears on discontinuation of therapy it is called ‘pseudoli-thiasis’.

In a patient with normal renal function, 60% of the drug is excreted

unchanged into the urine and 40% is excreted into the bile(32).

Ceftriaxone is an anion, can concentrate in bile 20 to 150 times more than

in serum and readily forms an insoluble salt with calcium (calcium-ceftriaxone)

that precipitates in gallbladder(33). The risk factors for ceftriaxone

pseudolithiasis are hypercalcemia, renal failure (leads to increase

biliary concentration), high dose (>2g or >200mg/kg/day), long-term

treatment and gallbladder stasis(34).

The incidence of ceftriaxone induced pseudolithiasis is

15% to 46% in various prospective studies(38-42). Usually pseudoliths

appear after 6 (range, 3 to 22) days of therapy and disappear after 15

(range, 2-63) days of discontinuation of therapy(35,36). Most cases of

ceftriaxone induced pseudolithiasis are asymptomatic and detected on

sonography but rarely (0-19% of cases)(36), they can produce symptoms like

pain abdomen, nausea, vomiting and biliary obstruction. In symptomatic

cases, discontinuation of drug is recommended. However, cessation of drug

therapy is unnecessary in incidentally detected asymptomatic cases of

ceftri-axone induce pseudolithiasis.

Low phospholipid associated cholelithiasis (LPAC)

Gallstones in the adolescent age group with a strong

family history of gallstones under the age of 40 years, intrahepatic

cholestasis of pregnancy or a cholestatic reaction to oral contraception

should raise the suspicion of a rare condition called low phospholipid

associated cholelithiasis (LPAC)(37). The underlying cause is a mutation

in MDR3, a gene which encodes the ABCB4 transporter. This protein is

responsible for the translocation of phosphatidyl-choline across the

canalicular membrane of hepato-cytes which then solubilises cholesterol in

bile. In the absence of phosphatidylcholine, bile becomes supersaturated

with cholesterol and predisposes to gallstone formation. This condition is

more frequent in females than in males (3:1). Apart from a family history

of cholesterol gallstones amongst first degree relatives, intrahepatic

hyperechoic foci (cholesterol crystal deposits in intrahepatic bile ducts)

are a characteristic sign of the LPAC syndrome. The typical biliary

symptoms experienced by these patients are probably due to cholesterol

crystal deposits and bile duct inflammation as symptoms recur in more than

half of the cases after cholecystectomy. Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA)

appears to relieve biliary symptoms long before the dissolution of

intrahepatic stones(38).

Clinical presentation

Table II summarizes the clinical presentations

at different age of presentation.

TABLE II

Clinical Presentations of Gallstones in Children(46,47)

| Age group |

Proportion of all gallstones in children |

Clinical presentations |

| Infants (< 2yrs) |

10% |

1. Symptomatic: Cholestatic jaundice, transient

acholic stools, abdominal pain, and sepsis. 2. Asymptomatic:

incidental detection. |

|

Children (2-14 yrs) |

40% |

1. Typical biliary symptoms (40%-50%): right upper quadrant or

epigastric pain with or without nausea, vomiting and fat

intolerance. |

| |

|

2. Non-specific abdominal pain (20%-30%). |

| |

|

3. Acute abdomen (5%-10%): due to acute cholecystitis, pancreatitis

or cholangitis. |

| |

|

4. Asymptomatic (20%). |

| Adolescents(14-18 yrs) |

50% |

Same as in children but right upper quadrant pain

and fatty food intolerance are more common in adolescents than in

children. |

Fetal Cholelithiasis

The prenatal diagnosis of fetal gallstones has been

reported since 1983(39) but is a rare finding and little is known about

the natural history and clinical significance. The most cases of fetal

cholelithiasis reported in the literature are detected in the third

trimester of pregnancy with no apparent sex predilection and all were

identified as incidental findings. The echogenic material detected in

fetal gallbladder is usually sludge as in most reported cases there was

lack of acoustic shadowing. The prognosis of fetal gallstones is very good

as complete spontaneous resolution has been documented in the majority of

cases between 1 and 12 months after birth and those that persist are

rarely symptomatic(40). There are several hypotheses put forward to

explain the formation of fetal gallstones but none are conclusive. Brown,

et al. have suggested that increased level of estrogen might

predispose to the formation of stones by increasing the secretion of

cholesterol and reducing the synthesis of bile acids(41). Other possible

predisposing factors are: use of narcotics in pregnant women, hemolytic

anemia, blood group incompatibility, structural abnormalities like

choledochal cyst, pregnancy induced cholestasis, etc.(42,43).

Cholelithiasis in infancy

Cholelithiasis is uncommon in infants but increasing

numbers are reported in recent years mainly due to increasing use of

ultrasonography (US). Gallstones in infancy are usually asymptomatic but

occasionally can present with cholestatic jaundice, transient acholic

stools, sepsis and abdominal pain. In symptomatic infants, gallstones are

more often associated with stones in the common bile duct (CBD) than

stones in the gallbladder alone(44,45). In a series of 13 cases of

cholelithiasis in infants, St-Vil, et al. have reported that 11

were asymptomatic and detected by US done for unrelated problems(44). In

another series of 40 cases of cholelithiasis in infancy, Debray, et al.

have shown that 6 had isolated gallstones and were asymptomatic whereas 34

had bile duct obstruction and were symptomatic(45).

Cholelithiasis in children

Children with gallstones can present with acute

abdominal pain due to cholecystitis, cholangitis or pancreatitis. However,

an acute presentation is uncommon (5% to 10% of cases only). Most

commonly, children with cholelithiasis present with typical right upper

quadrant pain (50%) or non-specific abdominal symptoms (25%) including

poorly localized abdominal pain and nausea. Around 20% of cases are

asymptomatic (incidentally detected stones)(11,46,47). Gallstones in

children are more often (60%) symptomatic than in adults (20%)(46). The

type of symptoms depend on the age of presentation, older children (6

years or more) often localize pain in the right upper quadrant whereas

younger children (5 years or less) tend to present with nonspecific

symptoms(11). Fatty food intolerance, a typical symptom of gallstone

disease in adults, tends to be reported by older children(47).

Cholelithiasis in adolescents

In this age group, the symptoms are similar to those

reported in adults. Fatty food intolerance, biliary colic and acute or

chronic cholecystitis are usual presenting features of symptomatic

patients(47).

Diagnosis

The universally used and the most accurate diagnostic

test in detecting the presence of gallstones is ultrasonography.

Gallstones are usually mobile, single or multiple and characteristically

cast an acoustic shadow. Biliary sludge though appearing echogenic on

ultrasound, does not cast an acoustic shadow. A stone, as small as 1.5 mm,

can be detected by ultrasonography. The sensitivity and specificity of

ultrasonography exceeds 95% for gallbladder cholelithiasis, but this

figure is only 50%-75% for choledocholithiasis. In children 20% to 50%

gallstones are radiopaque(48).

Cholescintigraphy, with technetium 99 m

labeled diisopropyl iminodiacetic acid (DISIDA), is the most accurate

method of diagnosing acute cholecystitis. Nonvisulization of the

gallbladder in an otherwise patent biliary system suggests acute

cholecystitis. Magnetic resonance cholangio-pancreatography (MRCP) is

being used increasingly to investigate complicated gallstone disease.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) offers the

additional advantage of therapeutic intervention in common bile duct

stones(49,50).

Management

Management of gallstones depends on the symptoms and

the age of the patient. Symptomatic gallstones need cholecystectomy and

same is true for complicated gallstones but there is no consensus about

the management of asymptomatic gallstones in children. In a prospective

study of children with non-pigmented gallstones, Bruch SW, et al.

followed 41 children with non-specific or no symptoms for 21 months(51).

Of these, 50% remained or became asymptomatic, 32% experienced definite

improvement in symptoms, 18% had continued symptoms but none had any

biliary complications. Wesdorp, et al.(11) have substantiated this

observation in their study of 82 children with cholelithiasis who were

followed up for a mean period of 4.6 years. The suggested treatment

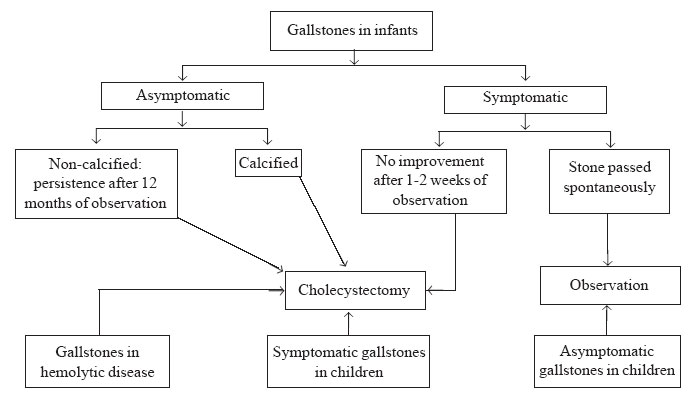

algorithm for gallstones in children is given in Fig.1.

Children with gallstones should be divided into two groups. Those with

typical symptoms (right upper quadrant or epigastric pain, nausea,

vomiting and fatty food intolerance) should have their gallbladders

removed. Asymptomatic children or children with nonspecific symptoms can

undergo safe follow up. These children will require observation into

adulthood to determine their lifetime risk of developing symptoms.

|

|

Fig. 1. Management algorithm for gallstones

in children. |

In recent years, laparoscopic cholecystectomy has

become the treatment of choice in the surgical management of children with

cholelithiasis. It has the advantage of being less invasive with lower

morbidity and mortality and shorter hospital stay over conventional open

cholecystectomy(52).

The role of dissolution therapy in the management of

gallstones in children remains to be defined. The only study of UDCA

therapy for gallstones in children by Gamba, et al.

have shown disappointing results(53). Of 15 children with radiolucent

stones (<10 mm) and a functional gallbladder treated for one year, stones

disappeared completely in only two cases but returned later in both.

Extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy for gallstones in

children has been successful in a single case report(54).

The approach to cholelithiasis in infancy is different as spontaneous

resolution has been reported in a significant proportion of cases (cholelithiasis

almost 50% and choledocholithiasis 30%)(44,45,55). Spontaneous resolution

within 6 months is more common with idiopathic gallstones than in patients

with known predisposing factors. Asymptomatic infants with idiopathic

cholelithiasis be observed for spontaneous resolution. Even for

choledocholithiasis, an observation period of 1-2 weeks is recommended

before active therapy as there is a chance of spontaneous resolution.

Cholecystectomy is indicated for symptomatic cholelithiasis, asymptomatic

choleli-thiasis persisting beyond 12 months and radiopaque calculi(44,45).

Management of cholelithiasis in hemolytic disease

In this group of children, screening with US is

recommended at around 5 years of age. Screening is also recommended before

splenectomy as both splenectomy and cholecystectomy can be combined in

presence of gallstones and it confers a survival benefit over splenectomy

alone in hereditary spherocytosis(56). However, there is no advantage of

doing cholecystectomy with splenectomy if there are no gallstones as these

patients are not at an increased risk of cholelithiasis after

splenec-tomy(57). In sickle-cell disease, prophylactic cholecystectomy is

recommended even for asympto-matic gallstones as it is difficult to

differentiate an acute abdominal crisis from acute cholecystitis, and the

morbidity and mortality of emergency cholecystectomy in this setting is

much higher than in elective cholecystectomy(58). To avoid sickling during

the perioperative period it is recommended that hemoglobin S be decreased

to at least 30% and total hemoglobin be increased to at least 11 g/dL.

During the surgery and recovery period, hypotension, dehydration, hypoxia,

hypothermia and acidosis should be prevented(47).

Choledocholithiasis

Most often common bile duct (CBD) stones are associated

with gallstones except in hemolytic conditions where these may be the

primary stones. Overall CBD stones are uncommon in children (only 10% of

all gallstones)(16,59), but infants have a higher incidence(45).

Clinical presentation of CBD stones comprises jaundice, cholangitis, and

gallstone pancreatitis. A CBD stone should also be suspected in a patient

with gallstones with hyperbilirubinemia (total bilirubin >1.3 mg/dL)

and/or a dilated CBD on US (>6 mm). The most appropriate method of

investigation and management of CBD stones seems to be laparoscopic

cholecystectomy (LC) with intraoperative cholangiogram (IOC) followed by

ERCP(60). In a study of 48 cases of suspected CBD stones, Mah, et al.

have compared preoperative ERCP followed by LC with LC+IOC followed by

ERCP(61). The diagnostic yield of ERCP in detecting CBD stone was just 23%

with the former approach compared with 100% with the latter approach.

|

Key Messages

• Gallstone disease is uncommon in children but

more cases are being diagnosed due to increasing use of

ultrasonography.

• Gallstones in infants most often resolve

spontaneously.

• Gallstones in a setting of hemolytic disease

develop after 5 years of age and require prophylactic

cholecystectomy.

• Asymptomatic gallstones or gallstones with

atypical symptoms may be observed as the natural history is benign. |

References

1. Rome Group for the Epidemiology and Prevention of

Cholelithiasis (GREPCO). The Epidemiology of gallstone disease in Rome,

Italy. Part I. Prevalence data in men. Hepatology 1988; 8: 904-906.

2. Bainton D, Davies GT, Evans KT, Gravelle IH.

Gallbladder disease. Prevalence in a South Wales Industrial Town. N Engl J

Med 1976; 294: 1147-1149.

3. Khuroo MS, Mahajan R, Zargar SA, Javid G, Sapru S.

Prevalence of biliary tract disease in India: a sonographic study in adult

population in Kashmir. Gut 1989; 30: 2001-2005.

4. Singh V, Trikha B, Nain CK, Singh K, Bose SM.

Epidemiology of gallstone disease in Chandigarh: A community-based study.

J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2001; 16: 560-563.

5. Malhotra SL. Epidemiological study of cholelithiasis

among railroad workers in India with special reference to causation. Gut

1968; 9: 290-295.

6. Kotwal MR, Rinchen CZ. Gallstone disease in the

Himalayas (Sikkim and North Bengal): causation and stone analysis. Indian

J Gastroenterol 1998; 17: 87-89.

7. Jayanthi V. Pattern of gallstone disease in Madras

city, south India-a hospital based survey. J Assoc Physicians India 1996;

44: 461-464.

8. Khan HN. Asymptomatic gallstones in the

laparo-scopic era. J R Coll Surg Edin Irel 2004; 2: 115.

9. Gracie WA, Ransohoff DF. The natural history of

silent gallstones: the innocent gallstone is not a myth. N Engl J Med

1982; 307: 798-800.

10. Schirmer WJ, Grisoni Er, Gauderer MWL. The spectrum

of cholelithiasis in the first year of life. J Pediatr Surg 1989; 24:

1064-1067.

11. Wesdorp I, Bosman D, de Graaff A, Aronson D, van

der Blij F, Taminiau J. Clinical presentations and predisposing factors of

cholelithiasis and sludge in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2000;

31: 411-417.

12. Palasciano G, Portincasa P, Vinciguerra V, Velardi

A, Tardi S, Baldassarre G, et al. Gallstone prevalence and

gallbladder volume in children and adolescents: an epidemiological

ultrasonographic survey and relationship to body mass index. Am J

Gastroenterol 1989; 84: 1378-1382.

13. Nomura H, Kashiwagi S, Hayashi J, Kajiyama W,

Ikematsu H, Noguchi A, et al. Prevalence of gallstone disease in a

general population of Okinawa, Japan. Am J Epidemiol 1988; 128: 598-605.

14. Ganesh R, Muralinath S, Sankarnarayanan VS,

Sathiyasekaran M. Prevalence of cholelithiasis in children – a

hospital-based observation. Indian J Gastroenterol 2005; 24: 85.

15. Kaechele V, Wabitsch M, Thiere D, Kessler AL,

Haenle MM, Mayer H, et al. Prevalence of gallbladder stone disease

in obese children and adolescents: influence of the degree of obesity, sex

and pubertal development. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2008;

42: 66-70.

16. Schweizer P, Lenz MP, Kirschner HJ. Pathogenesis

and symptomatology of cholelithiasis in childhood. Dig Surg 2000; 17:

459-467.

17. Webb DK, Darby JS, Dunn DT, Terry SI, Serjeant GR.

Gallstones in Jamaican children with homozygous sickle-cell disease. Arch

Dis Child 1989; 64: 693-696.

18. Tripathy D, Dash BP, Mohapatra BN, Kar BC.

Cholelithiasis in sickle cell disease in India. J Assoc Physicians India

1997; 45: 287-289.

19. do Santos Gumiero AP, Bellomo-Brandao MA,

Costa-Pinto EAL. Gallstones in children with sickle cell disease followed

up at a Brazilian hematology center. Arq Gastroenterol 2008; 45:

313-318.

20. Croom RD 3rd, McMillan CW, Orringer EP, Sheldon GF.

Hereditary spherocytosis. Recent experience and current concept of patho-physiology.

Ann Surg 1986; 203: 34-39.

21. Kar R, Rao S, Srinivas UM, Mishra P, Pati HP.

Clinico-hematological profile of hereditary spherocytosis: experience from

a tertiary care center in North India. Hematology 2009; 14: 164-167.

22. Kalayci AG, Albayrak D, Gunes M, Incesu L, Agac R.

The incidence of gallbladder stones and gallbladder function in beta-thalassemic

children. Acta Radiol 1999; 40: 440-443.

23. Lotfi M, Keramati P, Assadsangabi R, Nabavizadeh

SA, Karimi M. Ultrasonographic assessment of the prevalence of

cholelithiasis and biliary sludge in beta-thalassemia patients in Iran.

Med Sci Monit 2009; 15; CR398-402.

24. Origa R, Galanello R, Perseu L, Tavazzi D,

Cappellini MD, Terenzani L, et al. Cholelithiasis in thalassemia

major. Eur J Hematol 2008; 82: 22-25.

25. Galanello R, Piras S, Barella S, Leoni GB,

Cipollina MD, Perseu L, et al. Cholelithiasis and Gilbert’s

syndrome in homozygour beta-thalassemia. Br J Haematol 2001; 115: 926-928.

26. Chawla Y, Sarkar B, Marwaha RK, Dilawari JB.

Multitransfused children with thalassemia major do not have gallstones.

Trop Gastroenterol 1997; 18: 107-108.

27. Hussaini SH, Pereira SP, Veysey MJ, Kennedy C,

Jenkins P, Murphy GM, et al. Roles of gall bladder emptying and

intestinal transit in the pathogenesis of octreotide induced gall bladder

stones. Gut 1996; 38: 775-783.

28. Jawaheer G, Pierro A, Lloyd DA, Shaw NJ.

Gallbladder contractility in neonates: effects of parenteral and enteral

feeding. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 1995; 72: F200-202.

29. Roslyn JJ, Berquist WE, Pitt HA, Mann LL, Kangarloo

H, DenBesten L, Ament ME. Increased risk of gallstones in children

receiving total parenteral nutrition. Pediatrics 1983; 71: 784-789.

30. Matos C, Avni EF, Van Gansbeke D, Pardou A,

Struyven J. Total parenteral nutrition (TPN) and gallbladder diseases in

neonates - sonographic assessment. J Ultrasound Med 1987; 6:

243-248.

31. Schaad UB, Tschappeler H, Lentze MJ. Transient

formation of precipitations in the gallbladder associated with ceftriaxone

therapy. Pediatr Infect Dis 1986; 5: 708-710.

32. Richards DM, Heel RC, Brogden RN, Speight TM, Avery

GS. Ceftriaxone. A review of its antibacterial activity, pharmacological

properties and therapeutic use. Drugs 1984; 27: 469-527.

33. Shiffman ML, Keith FB, Moore EW. Pathogenesis of

ceftriaxone-associated biliary sludge. In vitro studies of calcium-ceftriaxone

binding and solubility. Gastroenterology 1990; 99: 1772-1778.

34. Lee SP, Lipsky BA, Teefey SA. Gallbladder sludge

and antibiotics. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1990; 9: 422-423.

35. Schaad UB, Wedgwood-Krucko J, Tschaeppeler H.

Reversible ceftriaxone-associated biliary pseudolithiasis in children.

Lancet 1988; 2: 1411-1413.

36. Schaad UB, Suter S, Gianella-Borradori A,

Pfenninger J, Auckenthaler R, Bernath O, et al. A comparison of

ceftriaxone and cefuroxome for the treatment of bacterial meningitis in

children. N Engl J Med 1990; 322: 141-147.

37. Rosmorduc O, Poupon R. Low phospholipid associated

cholelithiasis: association with mutation in the MDR3/ABCB4 gene. Orphanet

J Rare Dis 2007; 2: 29.

38. Rosmorduc O, Hermelin B, Poupon R. MDR3 gene defect

in adults with symptomatic intrahepatic and gallbladder cholesterol

cholelithiasis. Gastro-enterology 2001; 120: 1449-1467.

39. Beretsky I, Lankin DH. Diagnosis of fetal

cholelithiasis using real-time high resolution imaging employing digital

detection. J Ultrasound Med 1983; 2: 381-383.

40. Suma V, Marini A, Bucci N, Toffolutti T, Talenti E.

Fetal gallstones: sonographic and clinical observations. Ultrasound Obstet

Gynecol 1998; 12: 439-441.

41. Brown LD, Teele LR, Doubilet MP. Echogenic material

in the fetal gallbladder: sonographic and clinical observations. Radiology

1992; 182: 73-76.

42. Abbitt LP, Mc Ilhenuy J. Prenatal detection of

gallstones. J Clin Ultrasound 1990; 18: 202-204.

43. Stringer MD, Lim P, Cave M, Martinez D, Lilford RJ.

Fetal gallstones. J Pediatr Surg 1996; 31: 1589-1591.

44. St-Vil D, Yazbeck S, Luks FI, Hancock BJ,

Filiatrault D, Youssef S. Cholelithiasis in newborns and infants. J

Pediatr Surg 1992; 27: 1305-1307.

45. Debray D, Pariente D, Gauthier F, Myara A, Bernard

O. Cholelithiasis in infancy: A study of 40 cases. J Pediatr 1993; 122:

385-391.

46. Rief S, Sloven DG, Lebenthal E. Gallstones in

children. Am J Dis Child 1991; 145: 105-108.

47. Holcomb GW Jr, Holcomb GW III. Cholelithiasis in

infants, children and adolescents. Pediatric Rev 1990; 11: 268-274.

48. Millar AJW. Surgical disorders of the liver and

bile ducts and portal hypertension. In: Kelly DA editors, Disease

of the liver and biliary system in children, 3 rd

Edition, Wiley-Blackwell publication UK, 2008, pp 433-474.

49. Poddar U, Thapa BR, Bhasin DK, Prasad A, Nagi B,

Singh K. Endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography in the management

of pancreatobiliary disorders in children. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2001;

16: 927-931.

50. Prasad H, Poddar U, Thapa BR, Bhasin DK, Singh K.

Endoscopic management of post laparoscopic cholecystectomy bile leak in a

child. Gastrointest Endosc 2000; 51: 506-507.

51. Bruch SW, Ein SH, Rocchi C, Kim PCW. The management

of nonpigmented gallstones in children. J Pediatr Surg 2000; 35: 729-732.

52. Chan S, Currie J, Malik AI, Mahomed AA. Pediatric

cholecystectomy: shifting goalposts in the laparoscopic era. Surg Endosc

2008; 22: 1392-1395.

53. Gamba PG, Zancan L, Muraca M, Vilei MT, Talenti E,

Guglielmi M. Is there a place of medical treatment in children with

gallstones? J Pediatr Surg 1997; 32: 476-478.

54. Sokal EM, De Bilderling G, Clapuyt P, Opsomer RJ,

Buts JP. Extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy for calcified lower

choledocholithiasis in an 18-month-old boy. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr

1994; 18: 391-394.

55. Miltenburg DM, Schaffer R, Breslin T, Brandt ML.

Changing indications for pediatric cholecystec-tomy. Pediatrics 2000; 105:

1250-1253.

56. Marchetti M, Quaglini S, Barosi G. Prophylactic

splenectomy and cholecystectomy in mild here-ditary spherocytosis:

analyzing the decision in different clinical scenarios. J Intern Med 1998;

244: 217-226.

57. Sandler A, Winkel G, Kimura K, Soper R. The role of

prophylactic cholecystectomy during splenec-tomy in children with

hereditary spherocytosis. J Pediatr Surg 1999; 34: 1077-1078.

58. Al-Salem AH. Should cholecystectomy be performed

concomitantly with splenectomy in children with sickle-cell disease?

Pediatr Surg Int 2003; 19: 71-74.

59. Newman KD, Powell DM, Holcomb GW III. The

management of choledocholithiasis in children in the era of laparoscopic

cholecystectomy. J Pediatr Surg 1997; 32: 1116-1119.

60. Vrochides DV, Sorrells DL, Kurkchubasche AG,

Wesselhoeft CW Jr, Tracy TF Jr, Luks FI. Is there a role for routine

preoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography for suspected

choledo-cholithiasis in children? Arch Surg 2005; 140: 359-361.

61. Mah D, Wales P, Njere I, Kortan P, Masiakos P, Kim CW. Management

of suspected common bile duct stones in children: role of selective

intraoperative cholangiogram and endoscopic retrograde

cholangiopancreatography. J Pediatr Surg 2004; 39: 808-812.

|

|

|

|

|