|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2009;46: 933-938 |

|

Two Doses of Measles Vaccine Reduce Measles

Deaths |

|

Maya van den Ent, Satish Kumar Gupta and Edward Hoekstra

Correspondence to: Maya van den Ent, Health Specialist,

UNICEF, 3 UN Plaza, New York, USA.

Email: [email protected]

|

|

Abstract

Two doses of measles vaccine to children reduce

measles related deaths. The first dose is delivered through the routine

immunization system to infants and the 2nd dose through campaigns or

routine immunization system, whichever strategy reaches the highest

coverage in the country. Experience in 46 out of 47 measles priority

countries has shown that measles vaccination using mass vaccination

campaigns can reduce measles related deaths, even in countries where

routine immunization system fails to reach an important proportion of

children. The gradual adoption of this strategy by countries has

resulted in 74% reduction in measles related deaths between 2000 and

2007. The 2010 goal to reduce measles mortality by 90% compared with

2000 levels is achievable if India fully implements its plans to provide

a second dose measles vaccine to all children either through campaigns

in low coverage areas or through routine services in high coverage

areas. Full implementation of measles mortality reduction strategies in

all high burden countries will make an important contribution to

achieving Millennium Development Goal 4 to reduce child mortality by two

thirds in 2015 as compared to 1990.

Key words: Measles, Mortality, Supplemental immunization

activities, Two dose strategy.

|

|

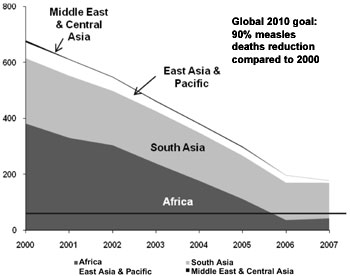

The introduction of a second dose for

measles vaccination using mass vaccination campaigns…,

along with improved routine immunization, has averted an estimated 3.4

million measles deaths between 2000 and 2007 in countries with previously

high measles burden. In the last nine years, 46 out of 47 countries with

more than 95% of the global measles deaths in 2000, introduced a 2nd

chance for measles vaccination, resulting in 74% reduction of measles

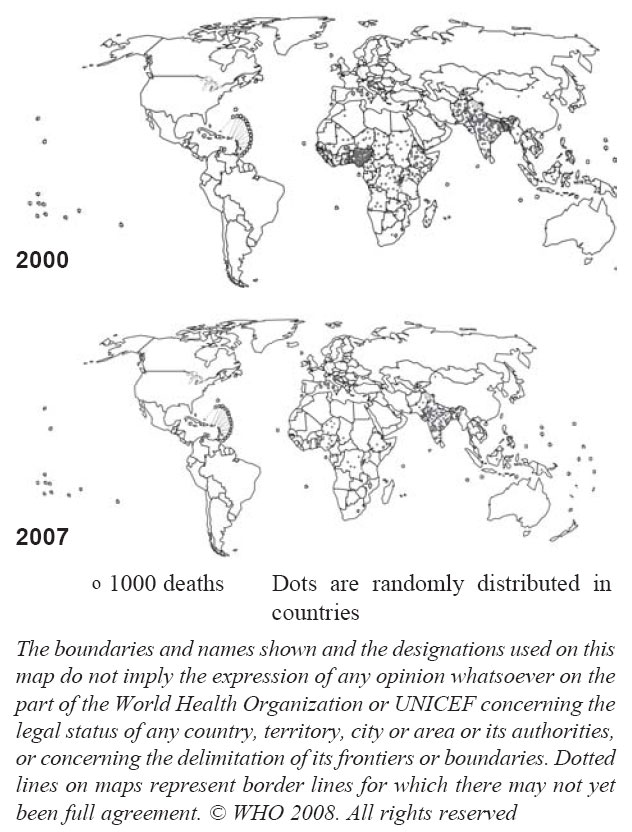

deaths between 2000 and 2007. Impressive progress was made in the African

region by 2006 and sustained in 2007, where measles deaths were reduced by

89% from 395,000 in 2000 to 45,000 in 2007(1,2) (Fig.1&2).

|

|

|

Fig. 1 Estimated measles death, 2000-2007 per region(1,2).

|

|

|

|

Fig. 2 Distribution of 750,000 estimated measles

deaths, 2000 and 2007(1,2).

|

In November 2008, the Strategic Advisory Group of

Experts (SAGE) on immunization has recommended that all children should

receive two doses of measles containing vaccine: the first dose during

routine vaccination program and the second dose either through routine

services or through mass campaigns (SIAs) …,

depending on which strategy achieves the higher coverage(3-5). This is an

important change to the previous recommendation that one dose of measles

containing vaccine would be sufficient to control measles.

As of 2009, all but one country has adopted a two dose

strategy for measles control. India is currently in the process of

introducing the 2nd dose of measles vaccination in their childhood

vaccination program. This is important, as one out of six people live in

India and an estimated 123,000 child deaths annually could be averted by

offering timely two doses of measles vaccine to Indian children(1,2).

Measles Kills

Measles is one of the most contagious viral diseases

and affected almost every child before widespread use of the measles

vaccine. About 6 million measles related deaths were estimated to occur

globally each year before the use of the live attenuated measles vaccine,

licensed in 1963(6). Although measles deaths in industrialized countries

are rare, measles is often fatal in developing countries with increased

risk of deaths for children under 5 years of age, those living in

overcrowded conditions, who are malnourished (especially with vitamin A

deficiency), and those with immunological disorders, such as advanced HIV

infection(7,8). Measles infection leads to immune suppression in the host,

lasting for up to one month, that reduces patients’ defenses against

complications such as pneumonia, diarrhea, and acute encephalitis.

Pneumonia, either a primary viral pneumonia or a bacterial

super-infection, is a contributing factor in about 60% of measles-related

deaths(7,8).

Globally, measles case fatality rates (CFR) vary widely

among countries, regions, age and within the same community in different

years. Higher CFRs occur in outbreaks, among children under 5 years of

age, in secondary cases, in cases with complications, and in unimmunized

individuals. Vaccination is associated with milder disease(7,8). Sudfield

and Halsey reviewed the CFRs of 25 studies in Indian communities,

presented elsewhere in this issue (mean CFR = 4.27%, range 0.00% - 31.25%,

median = 1.63%, range 0.00% - 31.25%). This review reveals that CFR

decreased over time, probably due to higher vaccination coverage. In

addition, children living in rural areas are more at risk of dying from

measles than those living in urban settings(9).

Control Strategies

After the introduction of measles vaccine in the

routine immunization program, along with improved nutrition, living

conditions and case management, measles related annual deaths reduced to

an estimated 2.5 million by 1980(10). As a result of the increase in

coverage with the 1st dose of measles to 72% in 2000, as compared to 16%

in 1980(11), a further substantial reduction in measles mortality was

achieved. Starting in the 1990s, an increasing number of countries

introduced a second dose of measles vaccine in their routine program, as

reported to WHO and UNICEF joint reporting system. The Pan American region

provided a second dose for measles in supplementary immunization

activities that resulted in the elimination of measles by 2002 in that

region (i.e. the region had no indigenous cases, as distinct from

imported cases, for more than 12 months)(12).

Despite these results, in 2000, measles was still the

leading cause of vaccine preventable deaths in children and the fifth

leading cause of death from any cause in children under five years

old(13). Responding to this situation, in 2001, the American Red Cross,

UNICEF, the United Nations Foundation, the CDC, and WHO launched the

Measles Initiative aimed at reducing the death rate from measles in

Africa, where nearly 60% of measles deaths were occurring(14). In 2004,

the Initiative extended its mandate to other regions (notably, Asia) where

measles was a significant burden. WHO and UNICEF identified 47 high-burden

countries for priority action. ……

All these countries had low coverage

of the measles first routine dose (with an average coverage of 58%) and

offered only one dose of measles vaccine to their children in 2000.

The Initiative adopted the WHO-UNICEF strategy to

reduce measles mortality (3-5,15) that is based on the experience in the

Americas:

• achieving high coverage of the first measles

containing vaccine (MCV1) in infants

• offer a second dose through campaigns (SIAs …)

or offer in the routine program reaching very high coverage;

• laboratory backed surveillance of new measles cases

to detect outbreaks and monitor progress; and

• enhanced case management, including vitamin A

supplementation.

Failure of Routine System to Reach Children

In the 47 high burden countries for measles ……,

the routine vaccination program reached on average only 58% of the infants

in 2000. Although the coverage increased to 72% in those countries by

2007, adding a 2nd dose to this weak program would not have resulted in a

significant increase of population immunity, as an important part of the

children are missed by the routine health delivery system. Therefore, a

different strategy was adopted to reach previously missed children and

increase population immunity.

In countries where the system fails to reach a large

part of the children, the only effective delivery system to reach over 95%

of the children nationwide is mass vaccination campaigns. Therefore,

offering the second dose through a campaign is the preferred strategy to

ensure sufficient children are protected from measles to significantly

reduce outbreaks. In the measles priority countries, an average of 28% of

children have not received their first dose of measles vaccination before

their first birthday in 2007, and in Niger, Chad, Somalia and Laos, more

than half of the children are missed through the routine system.

In 2007, 23 million infants did not receive the 1st

dose of measles vaccination. Two thirds of them live in eight countries:

India (8.5 million), Nigeria (2.0 million), China (1.0 million), Ethiopia

(1.0 million), Indonesia (0.9 million), Pakistan (0.8 million), DRC (0.6

million) and Bangladesh (0.5 million)(11).

Catch-up Campaigns in Areas With Poor Routine Immunization Coverage

Measles catch-up campaigns have been conducted in 46 of

the 47 priority countries that adopted the strategy and vaccinated all

children aged 9 months through 10-14 years, depending on the epidemiology

of the country ….

The impact of the campaigns has been overwhelming with over 90% reduction

in measles cases, and across Africa, many hospitals have closed their

measles wards.

Subsequently, every 2-4 years follow-up campaigns have

been conducted to administer the second measles dose to children born

after the previous campaign. The frequency of the follow-up campaigns

depends on the coverage of the routine immunization. Generally, major

outbreaks can be avoided by conducting follow-up campaigns before one

birth cohort of susceptible is reached.

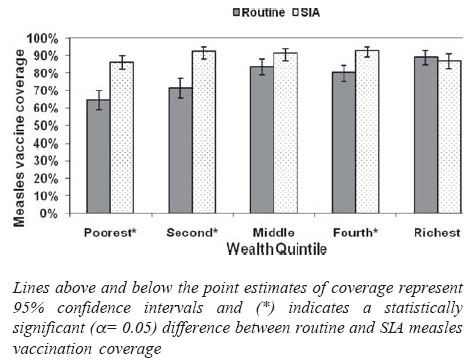

Well organized campaigns reach children across all

wealth quintiles evenly, whereas routine immunization program tends to

reach fewer children in the poorest quintiles. In Kenya, routine

vaccination reached 65% [95% CI: 59%-70%] of the children of the poorest

quintile, whereas 89% of the richest children were reached [95% CI:

85%-93%]. During the campaign the coverage was evenly distributed among

all wealth quintiles(16)(Fig.3). This indicates that

campaigns reach the unvaccinated children, including those from poorest

families.

|

|

|

Fig. 3 Nationwide

measles vaccination coverage among children aged 9-23 months through

routine vaccination immunization programme and SIA…,

Kenya 2002(16)

|

|

|

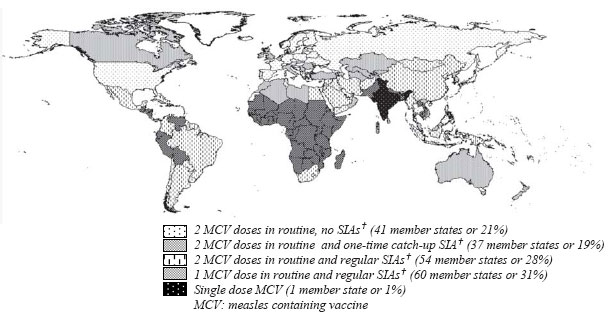

Fig. 4 Measles vaccination delivery

strategies, 2008. |

Realizing that measles is a more dangerous disease in

malnourished children and those living in overcrowded conditions, the

campaign approach seems an appropriate strategy to ensure that the poorest

children are reached and protected against measles.

Recently, countries have been organizing periodic

intensified routine immunization services or Child Health Days, where

routine immunization services, including measles vaccination, are offered

in underserved areas, often together with other life saving interventions.

This strategy has been adopted, as the number of un-immunized children

stagnated in recent years at more than 20 million. While health systems

take many years to develop and expand, extra outreach sessions can ensure

that the poorest children are also protected against vaccine preventable

diseases.

Integration

Measles vaccination has offered an excellent platform

to deliver other life saving interventions to the children, such as long

lasting insecticide treated nets, vitamin A, de-worming tablets, and polio

vaccines. Since 2001, the Measles Initiative with other partners has

supported the distribution of more than 37 million long lasting

insecticide treated nets for malaria prevention, 81 million doses of

de-worming medicine, more than 186 million doses of vitamin A, and more

than 95 million polio vaccines. Of the 33 countries conducting measles

SIAs in 2008, 29 (88%) integrated at least one other child survival

intervention with measles vaccination.

Two Dose Vaccination Schedules for Measles

To date, countries have adopted a delivery approach for

measles vaccine according to the capacity of their health system to reach

high population immunity. To stop transmission of measles virus, 93-95%

population immunity is needed, that requires a two dose schedule, as

vaccine efficacy after a single dose varies between 85 and 95%, depending

on the age at vaccination(5).

Countries with strong health systems deliver 2 doses in

the routine system only (41 of the 198 countries) or provide 2 doses

during the routine, in addition to having conducted a one- time catch-up

campaign (37 countries). Fifty-four countries provide two doses of measles

vaccines in the routine, and regularly conduct campaigns. Sixty countries

provide one dose of measles vaccination in the routine and conduct regular

campaigns. Finally, India has plans to begin introduction of a second dose

of measles vaccines in the near future (Fig.4).

Importantly, there are countries in each of the

categories that have successfully stopped measles transmission through

achieving and maintaining very high coverage with their delivery strategy,

with the exception of settings which use a single measles dose delivery

only.

According to the latest SAGE recommendations, it is

beneficial for countries to introduce a 2nd measles dose as part of the

routine vaccination programme, if the health system is sufficiently strong

and has reached at least 80% of the infants with the first measles dose

during 3 consecutive years. To ensure sufficient population immunity,

campaigns should be continued until the 1st and 2nd routine measles dose

reached 95% of the eligible children(4).

Conclusions

Significant reduction of mortality due to measles is

achieved by offering two doses of measles vaccines to all children. So

far, 46 of the 47 priority countries have adopted this strategy, further

reducing the measles related deaths by 74% between 2000 and 2007. In these

countries, all children are now offered two doses of measles vaccine, one

in the routine program and a second through campaigns by renewed delivery

strategies to reach previously unreached communities, besides closely

monitoring disease burden. Two of the 46 countries (Vietnam and Indonesia)

with stronger health systems have recently also started introducing 2nd

dose of measles in the routine immunization system.

Based on the experience in 46 out of 47 priority

countries, the 2010 goal to reduce measles mortality by 90% compared with

2000 levels(17) is achievable, if India fully implements its plans to

provide a second dose measles vaccine to all children either through

campaigns or through routine services. Full implementation of measles

mortality reduction strategies in all high burden countries will make an

important contribution to achieving Millennium Development Goal 4 to

reduce child mortality by two third in 2015, as compared to 1990.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Mickey Chopra, Maya

Vijayaraghavan, Maria Otelia Costales and Rouslan Karimov for their

contributions to the document and presentation of the data.

Funding: None.

Competing Interests: None stated.

Note: Authors are staff members of UNICEF. The

views expressed herein are those of the authors and not

necessarily reflect the views of UNICEF.

† Campaigns or

supplementary immunization activities (SIAs) are generally carried out

using 2 approaches. An initial, nationwide catch-up SIA targets all

children aged 9 months to 14 years; it has the goal of eliminating

susceptibility to measles in the general population. Periodic follow-up

SIAs then target all children born since the last SIA. Follow-up SIAs are

generally conducted nationwide every 2–4 years and target children aged

9-59 months; their goal is to eliminate any measles susceptibility that

has developed in recent birth cohorts and to protect children who did not

respond to the first measles vaccination.

††

The 47 measles priority countries are: Afghanistan,

Angola, Bangladesh, Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cambodia, Cameroon,

Central African Republic, Chad, Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the

Congo, Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gabon, Ghana,

Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, India, Indonesia, Kenya, Laos, Liberia, Madagascar,

Mali, Mozambique, Myanmar, Nepal, Niger, Nigeria, Pakistan, Papua New

Guinea, Republic of the Congo, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Somalia,

Sudan, Timor-Leste, Togo, Uganda, Tanzania, Vietnam, Yemen, and Zambia.

References

1. World Health Organization. Progress in global

measles control and mortality reduction, 2000-2007. Wkly Epidemiol Rec

2008; 49: 441-448.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Progress

in Global Measles Control and Mortality Reduction, 2000-2007. MMWR 2008;

57: 1303-1306.

3. World Health Organization. Meeting of the

immunization Strategic Advisory Group of Experts, November 2008-

conclusions and recommendations. Weekly Epidemiol Rec 2009; 84: 1-16.

4. World Health Organization. Meeting of the

immunization Strategic Advisory Group of Experts, April 2009- conclusions

and recommendations. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2009; 84: 213-236.

5. World Health Organization. Measles vaccines: WHO

position paper. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2009, 84: 349-360.

6. Clements CL, Hussey GD. Measles. In: Murray

CJL, Lopez AD, Mathers CD, eds. Global Epidemiology of Infectious

Diseases. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004.

7. Perry RT, NA Halsey. The clinical significance of

measles: a review. J Infect Dis 2004;189 (Suppl 1): S4-S16.

8. Wolfson LJ, Grais RF, Luquero FJ, Birmingham ME,

Strebel PM. Estimates of measles case fatality ratios: a comprehensive

review of community-based studies. Int J Epidemiol 2009, 38: 192-205.

9. Sudfield CR, Halsey NA. Measles case fatality ratio

in India; a review of community based studies: Indian Pediatr 2009; 46:

983-989.

10. Plotkin S, Orenstein W, Offit P. Vaccines, 5th ed.

Philadelphia: Saunders; 2008.

11. World Health Organization. United Nations

Children’s Fund. WHO/UNICEF review of national immunization coverage,

1980-2007. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2008. Available

at http://www.who.int/immunization_monitoring/routine/immunization_

coverage/en/index4.html. Accessed 20 September, 2009.

12. de Quadros CA, Andrus JK, Danovaro-Holliday MC,

Castillo-Solórzano C. Feasibility of global measles eradication after

interruption of trans-mission in the Americas. Expert Rev Vaccines,

2008; 7: 355-362.

13. Stein CE, Birmingham M, Kurian M, Duclos P, Strebel

P. The global burden of measles in the year 2000–a model that uses

country-specific indicators. J Infect Dis 2003;187 Suppl 1: S8-S14.

14. Wolfson L, Strebel P, Gacic-Dobo M, Hoekstra EJ,

McFarland JW, Hersh BS. Has the 2005 measles mortality reduction goal been

achieved? A natural history modelling study. Lancet 2007; 369: 191-200.

15. World Health Organization. United Nations

Children’s Fund. Measles mortality reduction and regional elimination

strategic plan 2001-2005. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization;

2001. Available at http://www.who.int/vaccines-documents/docspdf01/www573.pdf.

Accessed 20 September, 2009.

16. Vijayaraghavan M, Martin RM, Sangrujee N, Kimani GN,

Oyombe S, Kalu A, et al. Measles supplemental immunization

activities improve measles coverage and equity: Evidence from Kenya.

Health Policy 2007; 83: 27-36.

17. World Health Organization. Global immunization

vision and strategy 2006-2015. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health

Organization; 2005. Available at http://www.who.int/vaccines-documents/docspdf05/givs_final_en.pdf.

Accessed 20 September, 2009.

|

|

|

|

|