The novel coronavirus disease 2019

(COVID-19) was declared a pandemic by the World

Health Organization (WHO) on March 11, 2020. The

causative agent, severe acute respiratory syndrome

coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), attaches through its

viral surface spike proteins to the angiotensin

converting enzyme-2 (ACE-2) receptors on the

respiratory epithelial cells. Although several

months into the pandemic, there is a lack of clarity

regarding management of COVID-19 infection in

children. This review aims to summarize the key

clinical presentations and management of Pediatric

COVID-19 based on most pertinent available evidence.

The Medline database was searched for seminal

articles on COVID-19 presentation and management in

children less than 18 years of age. The latest

guidelines from World Health Organization (WHO) and

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW),

Government of India were also reviewed [1,2].

EPIDEMIOLOGY IN CHILDREN

Children account for less than 5%

of diagnosed COVID-19 infections worldwide [3]. As

per the MoHFW, 8% of the COVID-19 positive cases in

India were contributed by people below 17 years of

age [4].

Reports show a lower need for

hospital and intensive care unit (ICU) admission and

lower mortality rate (0-0.7%) in children compared

to adults [5]. This may be due to lower exposure,

strong innate immune response due to trained

immunity, healthier blood vessel endothelium,

excellent alveolar epithelium regeneration capacity

and fewer co-morbidities [6]. The community spread

of virus by children is of concern as a high rate of

asymptomatic infection is seen in younger age

groups. However, data show lower transmission rate

by children than adults [7,8].

CLINICAL FEATURES

The median age of presentation in

children ranged from 3.3-11 years in different

studies with a male preponderance [5,9,10]. When

compared to adults, majority of COVID-19 infected

children are asymptomatic with gastrointestinal and

mild respiratory manifestations being the commonest

[5,9-11]. Anosmia and ageusia are difficulty to

elicit in young children and reported less commonly

[5]. Other symptoms include lethargy, altered

sensorium, seizures, sore throat, fatigue, myalgias,

oligo-anuria, and skin rash. Severe or critical

disease (acute respiratory distress syndrome,

respiratory failure, shock, myocardial failure, and

multiorgan dysfunction) is described in less than

1-3% children [10]. Viral co-infections have been

reported in around 6% patients. Underlying

co-morbidities (underlying malignancy, nephrotic

syndrome, chronic disease of kidney, lung, or liver)

are associated in 9.9 - 42% of SARS-CoV-2 positive

children [12,13]. It is imperative to evaluate and

treat these common infections and co-morbidities as

COVID-19 may just be a bystander.

The COVID-19 disease

severity classification is presented in

Table I [1,14]. Indications for admission

include children with moderate, severe or critical

COVID-19 disease. Mild disease can be managed at

home. However, if the child has any underlying

co-morbidity or if home isolation is not feasible,

the child may managed at a COVID care centre or

hospital.

INVESTIGATIONS

All patients with moderate to

severe COVID-19 should undergo investigations as

detailed in Box I. Investigations to rule out

other possible differentials (like enteric fever,

dengue, malaria, etc.) should be done as indicated.

MANAGEMENT

Mild Cases

Mild cases should be isolated at

home, a community facility (COVID care-center) or a

health facility decided on a case-to-case basis

[1,2]. Pre-requisites for home isolation include apt

residential conditions for quarantine of patient and

family contacts, absence of co-morbidities and

presence of a caregiver with communication link to

the hospital. Strict adherence to home quarantine

guidelines is necessary [22]. Any difficulty in

breathing, grunting, inability to breast feed,

bluish discoloration of lips or face, dip in oxygen

saturation <95%, chest pain, mental confusion,

inability to arouse and reduced interaction when

awake should prompt urgent referral to a dedicated

COVID health center or hospital. Symptomatic

treatment should be given with antipyretic (Paracetamol)

for fever and pain when necessary, adequate

nutrition and rehydration, and identification and

treatment of any underlying co-morbidities or

co-infections. In children with symptomatic

respiratory tract infection, routine use of

antibiotics is not recommended except in situations

of suspected or confirmed bacterial co-infection.

Respiratory tract infection management should be

followed as per existing protocols [23].

Asymptomatic cases who are

incidentally detected like contacts of a diagnosed

case or planned for an elective surgery may be

isolated and monitored. A COVID positive status

during surgery may pose a risk for infection spread

and portend poor surgical outcome [24]. Therefore,

elective surgeries should be delayed until patients

test negative for COVID-19 [25,26].

Moderate Cases

Moderate cases should be treated

in a dedicated COVID health center or hospital with

detailed clinical history and regular assessment for

vital signs, work of breathing and oxygen saturation

(SpO2). Investigations as described in Table II

should be done at admission [1,2]. General

management should be done as stated above.

Additionally, the following may be considered [1,2].

i) Supplemental oxygen

therapy should be used for distressed breathing

or hypoxia (detailed below with management of

severe cases). Bronchodilators if required are

preferably delivered with an MDI and spacer

instead of a nebulizer.

ii) Empiric antibiotic

therapy may be given in under-five children. In

the absence of hypoxia, an oral antibiotic (amoxycillin-clavulanic

acid/azithromycin) may be added while

intravenous ceftriaxone (50-100 mg/kg/day in two

divided doses) may be started for moderate

COVID-19 cases with hypoxia or infiltrates on

chest X-ray.

iii) Chloroquine (5–10

mg/kg/day for 5-10 days) was used in children

with moderate to severe COVID disease in initial

months of the pandemic [27]. However, latest

evidence shows no role of chloroquine or

hydroxy-chloroquine in treatment of COVID-19

[28].

Close monitoring for disease

progression, repeat investigations at 48-72 hours if

needed and provision of transportation to dedicated

COVID care hospital should be available.

Severe and Critical Cases

All severe and critical COVID-19

cases should be admitted in a dedicated COVID care

hospital with detailed work-up as elucidated above.

Continuous monitoring of vitals, work of breathing

and SpO2 should be done.

i) All patients should be

started on empirical intravenous antibiotics

(third generation cephalosporins) within an hour

of arrival which should be escalated as per

clinical assessment.

ii) Aggressive

intravenous fluid resuscitation should be

avoided as it may worsen oxygenation.

iii) Experience of awake

proning in children is limited as their

tolerance may not be good and any agitation can

worsen hypoxia.

iv) Supplemental oxygen

therapy is required to maintain SpO2

³

94% while taking all precautions to minimize

aerosol generation.

The following modes of oxygen

delivery may be used:

Conventional oxygen therapy

may be given using nasal prongs/cannula,

oxygen mask or hood. Non-rebreathing mask can

provide up to 95% FiO2 at oxygen flow rate of 10 -15

L/ min and can be used for short periods initially

[29].

HHHFNC/HFNC (Heated humidified

high flow nasal canula) [30], is indicated in

patients with mild ARDS without evidence of

hemodynamic instability, altered mental status or

multi-organ failure. However, in absence of

response, consider early escalation to BiPAP/invasive

ventilation. Although, increased aerosolization risk

with HHHFNC has been speculated, the certainty of

evidence is low and it is a widely preferred option

in resource poor settings. A triple layer mask may

be used to cover the mouth and nose of the patient

over the nasal cannula to decrease aerosolization

[29].

Non-invasive Ventilation

BiPAP (Bilevel Positive

Airway Pressure): It is indicated for mild acute

respiratory distress syndrome without hemodynamic

instability, altered mental status or multi-organ

failure. However, its use is feasible only in an

older, cooperative child accepting of oronasal BiPAP

mask [29].

Bubble CPAP (Continuous

positive airway pressure) may also be used for

newborns and children with severe hypoxemia.

Invasive Ventilation

Tracheal intubation should be

performed when failure/contraindication of

BiPAP/HFNC occurs. The following specific

precautions are needed:

• Pre-oxygenate with a

non-rebreathing mask (NRM) or tight-fitting face

mask attached to a self-inflating bag with100%

oxygen for 5 minutes. Avoid bag and mask

ventilation (BMV) to limit aerosolization and if

required, use low tidal volumes.

• Follow Rapid sequence

intubation using sedation and analgesia (to

avoid cough reflex).

• Use a cuffed endotracheal

tubes (ETT)

• Ensure intubation by most

experienced person to minimize attempts and use

video laryngoscope for intubation to maintain

safe distance from patient.

• May use a plastic sheet to

cover the head, neck and chest of patient to

minimize contamination.

• Use disposable ventilator

circuits and hydrophobic viral filter between

the ventilator circuit at the expiratory end.

• Use closed suction to

minimize contact with secretion and aerosol

release.

The pediatric ARDS protocol for

management should be used. Prone ventilation

may be difficult to conduct in a child and

may unnecessarily increase the risk of infection to

the healthcare workers.

Extracorporeal membrane

oxygenation (ECMO) may be considered in patients

with continued severe hypoxemia despite maximal

ventilatory support.

Management of Shock

Standard care includes early

recognition and the initiation of antimicrobial

therapy and slow crystalloid fluid bolus within 1

hour of recognition and vasopressors for fluid

non-responsive hypotension. Further management may

be as per the Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines

for the management of septic shock in children [31].

Adjunctive Therapies for COVID-19

Steroids

:

Glucocorticoids may be considered for patients with

severe or critical COVID-19 disease with progressive

deterioration of oxygenation indicators, rapid

worsening on imaging and excessive activation of the

body’s inflammatory response. The recommended doses

include intravenous methylprednisolone 1 –

2mg/kg/day (maximum 80 mg) for 10 days or oral/

injectable dexamethasone 0.2-0.4 mg/kg/day OD

(maximum of 6 mg) for 5 days [1,2]. These

recommendations have been extrapolated from studies

conducted chiefly in adults. The UK-based RECOVERY

trial) reported dexamethasone to reduce mortality in

patients who required respiratory support [32]. The

proportion of children enrolled and analysed was not

clear.

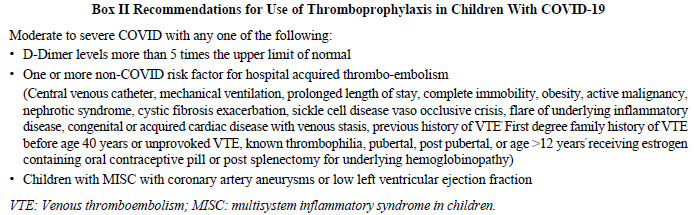

Anticoagulation [17,33]:

Recommendations for use in children are listed in

Box II. Thromboprophylaxis, both mechanical

(with sequential compression devices, where

feasible) and anticoagulation are recommended. Low

molecular weight heparin (enoxaparin) 1.5 IU/kg/dose

subcutaneous twice a day for <2 months age and 1

IU/kg/dose twice a day for >2 months should be used.

Unfractionated heparin may be used for children who

are clinically unstable or have severe renal

impairment as loading dose 75-100IU/kg intravenous

in 10 min followed by initial maintenance dose of 28

IU/kg/hour for age <1 year and 20 IU/kg/hour for

1-18 years (target aPTT between 65-80 seconds).

Anticoagulation therapy may be continued till

resolution of the hypercoagulable state or

resolution of the clinical risk factors for venous

thrombo-embolism [17].

|

Thromboprophylaxis is

contraindicated in active/major bleeding, need for

emergency surgery, platelets < 20,000/mm3,

concomitant aspirin administration at doses

>5 mg/kg/d and malignant hypertension.

Remdesivir: There are no

comparative clinical data evaluating the efficacy or

safety of remdesivir for COVID-19 in pediatric

patients. Although, initial guidelines

contraindicated its use in children < 12 years, the

US Food and Drug Administration issued an Emergency

Use Authorization (EUA) to permit the use of

remdesivir for treatment of COVID-19 in hospitalized

pediatric patients [34]. As per NIH guidelines,

remdesivir is indicated only in moderate COVID-19

with supplemental oxygen requirement where it

shortens the time to recovery [34,35]. It may be

considered in severe to critical COVID-19 (high flow

oxygen device, NIV, invasive ventilation or ECMO)

with dexamethasone (expert opinion) [34]. The latest

guidelines are similar for children albeit

extrapolated from adult data and recommended as a

part of clinical trials [36]. Few case series in

children show promise [37].

For children weighing > 40 kg, a

single loading dose of 200 mg on day 1 followed by

once daily dose of 100 mg from day 2 for 5-10 days

is used. For children weighing 3.5- 40 kg, a single

loading dose of 5 mg/kg on day 1 followed by 2.5

mg/kg once daily from day 2 for 5-10 days may be

given. The contraindications for its use include

AST/ALT > 5 times upper limit of normal (ULN) and

severe renal impairment (eGFR <30mL/min/m2

or need for hemodialysis). Remdesivir should not be

used in combination with chloroquine or

hydroxychloroquine [34].

Tocilizumab (TCZ): It is a

monoclonal antibody against interleukin-6 (IL-6)

receptor which emerged as an alternative treatment

for COVID-19 patients with cytokine storm. While

initial systematic reviews show that TCZ resulted in

reduction of mortality in severe COVID-19 cases

compared to the standard treatment, the latest

trials showed no benefit [38-40]. A larger ongoing

RCT which is also enrolling children may provide

clearer answers [41]. The use of TCZ is suggested

only in context of clinical trials [34] in those

with moderate/severe disease where

oxygen/ventilation requirement is increasing after

use of steroids with extensive bilateral lung

disease on radio-imaging [2,17]. The dose of TCZ for

>30 kg is 8 mg/kg (up to maximum of 800 mg) and <30

kg is 12 mg/kg given as intravenous infusion over 1

hour once, may be repeated if required at 12-24 hrs.

Contraindications to use include

patients with HIV, those with active infections

(uncontrolled systemic bacterial/fungal),

tuberculosis, active hepatitis (total bilirubin or

AST/ALT raised > 5 times ULN), ANC < 500-2000/mm3

and platelet count <50,000-1,00,000/mm3. Recipients

should be carefully monitored for secondary

infections, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia. All

patients should obtain a latent tuberculosis (TB)

test before TCZ therapy. If the text is positive,

treatment for tuberculosis should be started prior

to administration although, the risk for latent TB

reactivation is very compared to the benefit of

administering TCZ. Safety profile of TCZ in COVID-19

patients is yet to be understood.

Convalescent plasma therapy

(CPT): It may be considered in patients with

moderate disease who are not improving with

steroids. Few reports of its use in children with

severe COVID-19 show promise [42,43]. Special

considerations while using CPT include ABO

compatibility, neutralizing titre of donor plasma

above the specific threshold and avoidance of use in

patients with IgA deficiency or immunoglobulin

allergy. While adult trials have used doses of 4 to

13 ml/kg (usually 200 mL single dose) given slowly

over 2 hours, 2-4 mL/kg of convalescent plasma has

been used in children [43].

Other Agents Under Evaluation

Ivermectin, a potent in vitro

inhibitor of the COVID-19 causative virus

(SARS-CoV-2) with an established safety profile for

human use, was shown to be beneficial in COVID-19

[44]. A newer agent under evaluation is the

interleukin (IL)-1 inhibitor anakinra which may be

considered for immunomodulatory therapy (>4

mg/kg/day intravenous or subcutaneous) in COVID-19

with hyperinflammation. Initiation of anakinra

before invasive mechanical ventilation may be

beneficial [33]. Other potential treatments under

evaluation include interferon-beta, anti-IL-6

receptor monoclonal antibodies (sarilumab),

anti-IL-6 monoclonal antibody (siltuximab), Bruton’s

tyrosine kinase inhibitors, acalabrutinib,

ibrutinib, zanubrutinib) and Janus kinase

inhibitors (baricitinib, ruxolitinib, tofacitinib).

A recent trial has shown benefit of

baricitinib-remdesivir combination compared to

remdesivir alone in reducing recovery time in

COVID-19 patients [45]. However, there is

insufficient data for recommending use of any of

these agents in children except in the context of a

clinical trial [34].

Discharge Criteria and Follow-Up

The patient with mild to moderate

disease can be discharged after 10 days of symptom

onset and no fever or oxygen requirement for three

consecutive days with complete resolution of

symptoms prior to discharge [48]. Negative RT-PCR

before discharge is not required. Home quarantine

for 7 days post-discharge is necessary. Patients

with severe disease and immunocompromised states

(like cancer transplant recipients and HIV) should

have complete resolution of symptoms and negative

RT-PCR test report prior to discharge [48].

MULTISYSTEM INFLAMMATORY SYNDROME

IN CHILDREN (MIS-C)

MIS-C is a post-infectious

inflammatory response syndrome (characterized by

high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines CTNF, IL-6

and IL-1

b)

following SARS-CoV-2 infection. Various diagnostic

criteria have been provided by WHO and CDC

[33]. A tiered investigational approach is

followed in patients without life-threatening

manifestations, while work-up is done simultaneously

for the sick children [33]. Patients may require

additional investigations to rule out any

co-infection/other cause of illness.

Children with life threatening

manifestations should be admitted in PICU

management. Children with acute COVID inflammation

(RT-PCR positive) with symptoms like Kawasaki

disease (KD) should receive intravenous

immunoglobulin (IVIG) (dose-2g/kg over 1-2 days) and

remdesivir if available. Children with remote COVID

infection with KD symptom overlap should receive

IVIG and aspirin (20–25 mg/kg/dose every 6 hourly or

80-100 mg/kg/day) steroids may be added. In children

with remote COVID infection with predominant

cardiovascular involvement (myocarditis/cardiogenic

shock/distributive shock) with or without KD symptom

overlap IVIG, 3-day pulse of methylprednisolone with

tapering and LMWH prophylaxis are to be considered

as disease modifying agents [46].

Sick children should receive

initial broad-spectrum antibiotics considering

symptom overlap with severe bacterial infection.

Ceftriaxone or meropenem with vancomycin or

clindamycin or teicoplanin may be used for the

sickest children. In stable patients with MIS

overlap, with mild lab abnormalities and lacking

alternate diagnosis, ceftriaxone may be given.

Metronidazole is added if gastro-intestinal symptoms

are predominant.

All children with MIS-C require

ongoing clinical monitoring while laboratory

investigations may be repeated every 24-48 hourly as

guided by the clinical condition [47].

Contributors: PKS: reviewed

literature, drafted the manuscript; UJ:

conceptualized, drafted and critically appraised the

manuscript; AD: drafted and critically appraised the

manuscript.

Funding: None; Competing

interests: None stated.

REFERENCES

1. Clinical management of

COVID-19. Interim guidance. WHO. Published 27 May

2020. Available from:

https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/clinical-management-of-covid-19.

Accessed September 18, 2020.

2. Updated Clinical Management

Protocol for COVID-19. Ministry of Health and Family

Welfare. Government of India. Published July 3,

2020. Accessed August 3, 2020. Available from:https://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/UpdatedClinical

ManagementProtocolforCOVID19dated03072020.pdf.

3. Wu Z, McGoogan JM.

Characteristics of and important lessons from the

coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in

China: Summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the

Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

JAMA. 2020; 323:1239.

4. Coronavirus in India: 54%

COVID-19 cases in age group 18-44 years, 51% deaths

among those aged 60 years and above. Published Sep

02, 2020. Accessed September 18, 2020. Available

from:

https://www.financialexpress.com/lifestyle/health/coronavirus-in-india-54-pc-covid-19-cases-in-age-group-18-44-years-51-pc-deaths-among-those-aged-60-years-and-above/2072525/.

5. Rabinowicz S, Leshem E,

Pessach IM. COVID-19 in the pediatric

population-review and current evidence. Curr Infect

Dis Rep. 2020;22:29.

6. Dhochak N, Singhal T, Kabra

SK, Lodha R. Pathophysiology of COVID-19: Why

children fare better than adults? Indian J Pediatr. 2020;87:537-46.

7. Rajmil L. Role of children in

the transmission of the COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid

scoping review. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2020;4:e000722.

8. Viner RM, Mytton OT, Bonell C,

et al. Susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection among

children and adolescents compared with adults: A

systematic review and meta-analysis [published

online ahead of print, 2020 Sep 25]. JAMA

Pediatr. 2020; e204573.

9. Dong Y, Mo X, Hu Y, et al.

Epidemiology of COVID-19 among children in China. Pediatrics.

2020;145:e20200702.

10. Meena J, Yadav J, Saini L,

Yadav A, Kumar J. Clinical features and outcome of

SARS-CoV-2 infection in children: A systematic

review and meta-analysis. Indian Pediatr. 2020;

57:820-26.

11. Pei Y, Liu W, Masokano IB, et

al. Comparing Chinese children and adults with

RT-PCR positive COVID-19: A systematic review. J

Infect Public Health. 2020;13:1424-31.

12. Garazzino S, Montagnani C,

Donà D, et al. Multicentre Italian study of

SARS-CoV-2 infection in children and adolescents,

preliminary data as at 10 April 2020. Euro Surveill.

2020;25: 2000600.

13. Swann OV, Holden KA, Turtle

L, et al. Clinical characteristics of children and

young people admitted to hospital with covid-19 in

United Kingdom: Prospective multicentre

observational cohort study. BMJ. 2020;370:m3249.

14. Pediatric Acute Lung Injury

Consensus Conference Group. Pediatric acute

respiratory distress syndrome: Consensus

recommendations from the Pediatric Acute Lung Injury

Consensus Conference. Pediatr Crit Care

Med. 2015;16: 428-39.

15. Kosmeri C, Koumpis E,

Tsabouri S, Siomou E, Makis A. Hematological

manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 in children. Pediatr

Blood Cancer. 2020;67:e28745.

16. Katal S, Johnston SK,

Johnston JH, Gholamrezanezhad A. Imaging findings of

SARS-CoV-2 infection in Pediatrics: A systematic

review of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in 850

patients [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jul

30]. Acad Radiol. 2020;S1076-6332:30454-2.

17. Goldenberg NA, Sochet A,

Albisetti M, et al. Consensus-based clinical

recommendations and research priorities for

anticoagulant thromboprophylaxis in children

hospitalized for COVID-19-related illness. J Thromb

Haemost. 2020;18: 3099-105.

18. Koçak G, Ergul Y, Niºli K, et

al. Evaluation and follow-up of pediatric COVID-19

in terms of cardiac involvement: A scientific

statement from the Association of Turkish Pediatric

Cardiology and Pediatric Cardiac Surgery. Anatol J

Cardiol. 2020;24:13-18.

19. Henry BM, Aggarwal G, Wong J,

et al. Lactate dehydrogenase levels predict

coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) severity and

mortality: A pooled analysis. Am J Emerg Med.

2020;38:1722-6.

20. Mojtabavi H, Saghazadeh A,

Rezaei N. Interleukin-6 and severe COVID-19: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Cytokine

Netw. 2020;31:44-9.

21. Han J, Gatheral T, Williams

C. Procalcitonin for patient stratification and

identification of bacterial co-infection in

COVID-19. Clin Med (Lond). 2020;20:e47.

22. Revised guidelines for home

isolation of very mild/pre-symptomatic/asymptomatic

COVID-19 cases. Government of India Ministry of

Health & Family Welfare. Published July 2, 2020.

Available at:

https://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/Revised HomeIsolation

Guidelines.pdf. Accessed September 18, 2020.

23. Balasubramanian S, Rao NM,

Goenka A, Roderick M, Ramanan AV. Coronavirus

Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Children - What we know

so far and what we do not. Indian Pediatr.

2020;57:435-42.

24. COVID Surg Collaborative.

Mortality and pulmonary complications in patients

undergoing surgery with perioperative SARS-CoV-2

infection: An international cohort study [published

correction appears in Lancet. 2020 Jun

9]. Lancet. 2020;396:27-38.

25. Chan Y, Banglawala SM, Chin

CJ, et al. CSO (Canadian Society of Otolaryngology -

Head & Neck Surgery) position paper on rhinologic

and skull base surgery during the COVID-19

pandemic. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;49:81.

26. Morris M, Pierce A, Carlisle

B, Vining B, Dobyns J. Pre-operative COVID-19

testing and decolonization. Am J Surg.

2020;220:558-60.

27. Pastick KA, Okafor EC, Wang

F, et al. Review: Hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine

for treatment of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19). Open Forum

Infect Dis. 2020;7:ofaa130.

28. Takla M, Jeevaratnam K.

Chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, and COVID-19:

Systematic review and narrative synthesis of

efficacy and safety [published online ahead of

print, 2020 Nov 13]. Saudi Pharm J.

2020;10.1016/j.jsps.2020.11.003.

29. Sundaram M, Ravikumar N,

Bansal A, et al. Novel Coronavirus 2019 (2019-nCoV)

Infection: Part II - Respiratory Support in the

Pediatric Intensive Care Unit in Resource-limited

Settings. Indian Pediatr. 2020;57:335-42.

30. Agarwal A, Basmaji J,

Muttalib F, et al. High-flow nasal cannula for acute

hypoxemic respiratory failure in patients with

COVID-19: Systematic reviews of effectiveness and

its risks of aerosolization, dispersion, and

infection transmission. Can J Anaesth.

2020;67:1217-48.

31. Weiss SL, Peters MJ,

Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving sepsis Campaign

International Guidelines for the Management of

Septic Shock and Sepsis-associated Organ Dysfunction

in Children. Pediatr Crit Care Med.

2020;21:e52-e106.

32. RECOVERY Collaborative Group,

Horby P, Lim WS, et al. Dexamethasone in

Hospitalized Patients with Covid-19 - Preliminary

Report [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jul

17]. N Engl J Med. 2020;NEJMoa2021436.

33. Henderson LA, Canna SW,

Friedman KG, et al. American College of Rheumatology

Clinical Guidance for Pediatric Patients with

Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children

(MIS-C) Associated with SARS-CoV-2 and

Hyperinflammation in COVID-19. Version 1 [published

online ahead of print, 2020 Jul 23]. Arthritis

Rheumatol. 2020;10.1002/art.41454.

34. COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines

Panel. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Treatment

Guidelines. National Institutes of Health. Available

from: https://www.covid19treatmentguide

lines.nih.gov/ Accessed October 20, 2020.

35. Beigel JH, Tomashek KM, Dodd

LE, et al. Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid-19

- final report. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1813-26.

36. Chiotos K, Hayes M, Kimberlin

DW, et al. Multicenter interim guidance on use of

antivirals for children with COVID-19/SARS-CoV-2

[published online ahead of print, 2020 Sep 12]. J

Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2020;piaa115.

37. Méndez-Echevarría A,

Pérez-Martínez A, Gonzalez Del Valle L, et al.

Compassionate use of remdesivir in children with

COVID-19 [published online ahead of print, 2020 Nov

16]. Eur J Pediatr. 2020;1-6.

38. Aziz M, Haghbin H, Sitta EA,

et al. Efficacy of Tocilizumab in COVID-19: A

systematic review and meta-analysis [published

online ahead of print, 2020 Sep 12]. J Med Virol.

2020;10.1002/jmv.26509.

39. WHO SOLIDARITY Trial

Consortium, Pan H, Peto R, Karim Q, et al.

Repurposed antiviral drugs for COVID-19 – interim

WHO SOLIDARITY trial results. MedRxiv 2020.

40. Furlow B. COVACTA trial

raises questions about tocilizumab’s benefit in

COVID-19. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020;2:e592.

41. Covid-19: The inside story of

the RECOVERY trial. BMJ. 2020;370:m2800.

42. Piechotta V, Chai KL, Valk

SJ, et al. Convalescent plasma or hyperimmune

immunoglobulin for people with COVID-19: A living

systematic review. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

2020;7:CD013600.

43. Diorio C, Anderson EM,

McNerney KO, et al. Convalescent plasma for

pediatric patients with SARS-CoV-2-associated acute

respiratory distress syndrome [published online

ahead of print, 2020 Sep 4]. Pediatr Blood Cancer.

2020;e28693

44. Padhy BM, Mohanty RR, Das S,

Meher BR. Therapeutic potential of ivermectin as add

on treatment in COVID 19: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2020;23:462-9.

45. Kalil AC, Patterson TF, Mehta

AK, et al. Baricitinib plus remdesivir for

hospitalized adults with Covid-19 [published online

ahead of print, 2020 Dec 11]. N Engl J Med.

2020;10.1056/NEJMoa2031994.

46. Bhat CS, Gupta L,

Balasubramanian S, Singh S, Ramanan AV.

Hyperinflammatory syndrome in children associated

with COVID-19: Need for awareness. Indian Pediatr.

2020;57: 929-35.

47. Hennon TR, Penque MD,

Abdul-Aziz R, et al. COVID-19 associated multisystem

inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C)

guidelines; A Western New York approach [published

online ahead of print, 2020 May 23]. Prog Pediatr

Cardiol. 2020;101232.

48. Revised discharge policy for COVID-19.

Government of India. Ministry of Health and Family

Welfare. Published on 8 May, 2020. Accessed

September 18, 2020. Available from:

https://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/ReviseddischargePolicyforCOVID19.

pdf