Neonatal chylothorax is an abnormal accumulation

of lymphatic fluid in the pleural space which can be either

congenital or acquired. Nearly 90% of all in utero pleural

effusions are chylothorax [1]. The estimated incidence of

congenital chylothorax is 4 per lakh [2], with mortality

ranging from 30-50%. [3]. We herein report a late preterm

girl identified antenatally at 31 weeks of gestation with

severe bilateral pleural effusion for which thoracoamniotic

shunt was placed and subsequently diagnosed with congenital

chylothorax after delivery.

A 37-year-old lady,

G3P1A1L1 was admitted at 365/7 weeks for delivery of

hydropic fetus. Antenatal follow up had been uneventful till

31 weeks when ultrasonography showed hydropic changes in the

fetus with bilateral pleural effusion and subcutaneous

edema. A therapeutic fetal pleurocentesis was done with

amniocentesis. Chromosomal analysis and microarray on

amniotic fluid was negative. Mother had a negative indirect

coomb’s test, with serology negative for VDRL, and TORCH.

Parvo Virus PCR was negative, and she had a normal HbA1C and

Hemoglobin electrophoresis. Pleural fluid examination showed

205 leucocytes per cu.mm, 80% lymphocytes, LDH 87 U/L and a

protein of 1.8g/dL. Follow up scan at 33 weeks showed a

return of significant pleural effusion. Rather than opting

for preterm delivery, a right Rodeck thoracoamniotic shunt

was placed. Subsequent USG showed resolution of effusion on

the Right side with lung expansion and satisfactory interval

growth with normal fetal Dopplers. The left pleural effusion

was drained just prior to the delivery.

A female baby

with birth weight of 3015 g was delivered at 365/7 week

gestation by elective LSCS. Baby had signs of labored

breathing at birth, and was intubated and ventilated. Chest

X-ray showed right side pneumothorax and left side pleural

effusion for which bilateral intercostal tube drains (ICD)

were inserted. Pleural fluid was clear exudate (Protein –

2.6 g/dL) with 3638 cells/mm3, predominantly lymphocytes and

1.9% neutrophils. Post ICD insertion baby improved and was

extubated to high flow nasal cannula (HFNC).

Echocardiography and ultrasound abdomen and cranium were

normal. Once feeds were started pleural fluid became milky

in nature. Pleural fluid sent for analysis showed rise in

triglyceride level from baseline 35.8 mg/dL on Day 1 to 134

mg/dL on day 6 confirming the diagnosis of chylothorax.

|

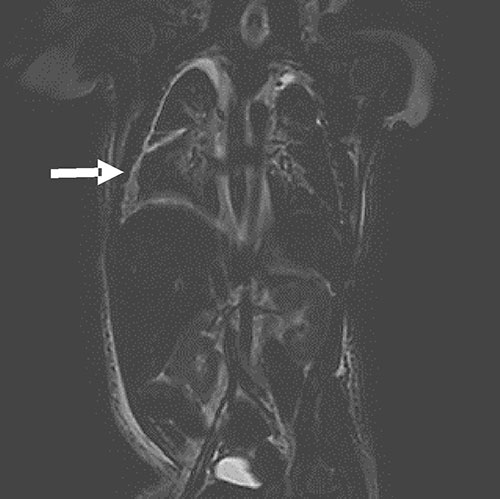

| Fig. 1 MRI

image (T2 SPAIR, coronal diffusion weighted

sequence) showing bilateral pleural effusion (R>L),

prominent tortuous lymphatic channels in thoracic

region extending into upper abdomen, with no

evidence of any mediastinal mass. |

MRI Chest was done on Day 8 of life for central

lymphatic anatomy and intrathoracic mass lesions. It showed

prominent tortuous lymphatic channels along with prominent

azygous vein

(Fig. 1). Baby was started on

medium chain triglyceride formula on day 9 of life in view

of chylothorax. Feeds had to be discontinued and parenteral

nutrition restarted along with injection Octreotide on day

12 because of increasing chyle drainage. Following this,

chyle formation reduced and the intercostal drains were

removed on day 16. Post drain removal there was an increase

in pleural effusion (right >left) which was organizing and

non-tappable. Octreotide infusion was increased in view of

persistent collection (at 10 mcg/kg/hr). Immunoglobulin

levels were low for which single dose IVIG was given. On Day

25, lymphoscintigraphy was done to rule out lymphatic

dysplasia, which was reported as normal. Feeds were

restarted on day 28, after which there was worsening in

respiratory distress but there was no increase in pleural

effusion; as monitored by ultrasound. Keeping the

possibility of leaky pulmonary lymphatics causing increase

in pulmonary interstitial fluid, diuretics were added, to

which baby responded well and feeds were gradually

increased. Diuretics were continued till day 41 of life.

Octreotide infusion was tapered gradually. Clinical exome

testing done which showed no pathogenic variants causative

of the phenotype, but variants of uncertain significance

were detected (lymphatic malformation-3, OMIM#613480). Baby

was discharged on day 44 of life on MCT- based formula

(Pregestimil).

Congenital chylothorax can be an

isolated finding or may be associated with genetic

conditions. Early antenatal detection and management by

placement of fetal pleuroamniotic shunt improves perinatal

outcome by avoiding complications due to pulmonary

hypoplasia [4]. Irrespective of the cause, initial postnatal

management consists of drainage of pleural fluid,

appropriate ventilation, total parenteral nutrition and

dietary modi-fication (conservative approach). Medication

and surgery may be required in refractory cases. Most

chylothorax cases improve spontaneously because of the

natural course of the disease. In newborns it is important

to distinguish neonatal chylothorax from congenital

lymphatic dysplasia, as the latter is difficult to treat and

has poorer prognosis.

As increased chyle formation

is associated with immunological and nutritional

complications, we had started octreotide on day 12. On

reviewing literature [5,6] we could not find any practice

recommendations for use of octreotide. The lymphatic

malformation-3 may explain the localized edema in neck,

genitals and probably in lungs, which persisted at time of

tapering of octreotide infusion.

To conclude,

optimum management of such cases is still a matter of

debate, but prenatal evaluation and management is associated

with improved survival. Postnatally we should follow

conservative approach for few weeks to give enough time for

the lymphatics to heal and develop collaterals [6].

Refractory cases would require additional therapy.

Contributors: RS: drafted the case report and revised it

critically for important intellectual content, involved with

management of case; TJA: revision of case report for

important intellectual content, involved with case

management, approved the version to be published; SG:

involved with case management, approved the version to be

published.

Funding: None; Competing interest: None

stated.

REFERENCES

1. Rocha

G, Fernandes P, Rocha P, Quintas C, Martins T, Proença E .

Pleural effusions in neonate. Acta Paediatr. 2006;95:791-8.

2. Bialkowski A, Poets CF, Franz AR. Congenital

chylothorax: A prospective nationwide epidemiological study

in Germany. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2015;100:F169.

3. Dorsi M, Giuseppi A, Lesage F, Stirnemann J, De Saint

Blanquat L, Nicloux M, et al. Prenatal factors associated

with neonatal survival of infants with congenital

chylothorax. J Perinatol. 2017;38:31-4.

4. Lee C,

Tsao P, Chen C, Hsieh W, Liou J, Chou H. Prenatal therapy

improves the survival of premature infants with congenital

chylothorax. Pediatr Neonatol. 2016;57:127-32.

5.

Bellini C, Cabano R, De Angelis L, Bellini T, Calevo M,

Gandullia P, et al. Octreotide for congenital and acquired

chylothorax in newborns: A systematic review. J Paediatr and

Child Hlth. 2018;54:840-7.

6. Beghetti M, La Scala G,

Belli D, Bugmann P, Kalangos A, Le Coultre C. Etiology and

management of pediatric chylothorax. J Pediatr.

2000;136:653-8.