|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2020;57:

469-470 |

|

Developmental Delay with Intermittent Twisting of Neck

|

|

Rangan Srinivasaraghavan and Samuel P Oommen*

Developmental Pediatrics unit, Christian Medical College and

Hospital,

Vellore, India.

Email:

[email protected]

|

|

The hallmark of cerebral palsy (CP) is the presence of pyramidal

or extra-pyramidal signs [1]. There are many disorders that can mimic CP

[2]. One such mimicking condition is high cervical cord compression due

to anomalies of the spinal cord [3].

A two-year-old boy, second

of twins born of non-consanguineous marriage, was brought with inability

to stand. He was delivered at eight months of gestation with a weight of

1.5 kg and no significant neonatal complications. His motor milestones

were significantly delayed compared to his twin and spasticity was

noticed from six months of age. The parents reported stiffness of his

neck and limbs which was more on waking up, which would decrease within

a few minutes. There were no seizures or regression of milestones. He

was diagnosed to have mixed (spastic-dystonic) cerebral palsy. His

language and social skills were age appropriate. At presentation, he was

using two- word phrases and had attained daytime bowel and bladder

control.

On examination, weight, height and head circumference

were within normal limits. There were no obvious dysmorphic features.

His upper segment to lower segment ratio was 0.92 suggestive of truncal

shortening. His vision and hearing were normal. There was hypertonia in

all the four limbs and brisk deep tendon reflexes. The plantar responses

were extensor bilaterally. Examination of the other systems was

unremarkable.

|

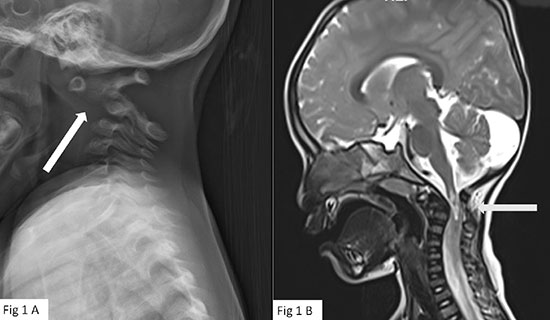

| Fig. 1 (a) X-ray

Cervical spine lateral view flexed position showing

widened pre-dentate space (white arrow); (b)

MRI T2 weighted image sagittal section showing

compression of the cord at C1 level (grey arrow). |

Lateral X-ray of the neck (Fig. 1a) showed anterior

dislocation of C1 vertebra. The pre-dentate space was widened

and measured 13 mm. MRI did not show any periventricular or

basal ganglia changes. MRI of the cervical spine (Fig. 1b)

(confirmed atlanto-axial dislocation (AAD) causing compressive

myelopathy at C1 level, without any other spinal malformations.

Neurosurgeon prescribed neck collar, and advised follow-up for

cervical spine stabilization. In view of the truncal shortening

and AAD, he was also advised evaluation for skeletal dysplasia,

but the parents deferred it to a later date.

Conditions

which mimic CP should be considered – when there is absence of

definite preceding perinatal insult; there is family history of

developmental delay and spasticity; there is developmental

regression or onset of new clinical signs of upper motor

involvement; and when there is associated significant ataxia,

muscle atrophy, or sensory loss [2]. Although neuroimaging is

not essential for making a diagnosis of CP, MRI brain is

abnormal in more than 80% of children with CP [4]. Current

Western guidelines recommend MRI in children suspected to have

CP [1]. The imaging not only uncovers the pathogenic patterns

responsible for the CP but can also detect structural

malformations of the brain and neuro-metabolic problems which

resemble CP [4].

Despite significant perinatal risk

factors, the inter-mittent abnormal neck stiffness warranted

meticulous examination and evaluation [3], which revealed AAD

can be idiopathic or due to traumatic, inflammatory or genetic

disorders like Down syndrome, achondroplasia, cleido-cranial

dysplasia and Morquio syndrome [4]. Neuro-logical manifestations

of congenital AAD in children result from progressive

compression of the cervico-medullary junction and present as

progressive quadri-plegia. Patients with myelopathy may go

undiagnosed for a long period because of very slow progression

of the disease process [3] and maybe mistakenly diagnosed as CP.

Trauma or sudden movement can worsen symptoms in AAD. In the

reported child, the increase in stiffness upon getting from

sleep could possibly be due to the fact that while he was lying

down, neck positioning could have caused an increase in

stiffness. Poor cervical posture during sleep could cause

increased biomecha-nical stresses on the structure of the

cervical spine and could result in cervical pain and stiffness

[5].

This case highlights compressive myelopathy as a

differential for CP, and underscores the importance of a good

history-taking in all patients, especially those labelled as

cerebral palsy.

Contributors: Both authors were involved

in clinical care, literature search and manuscript preparation.

Funding: None; Competing interest: None Stated.

References

1. Himmelmann K, Horber V, De

La Cruz J, Horridge K, Mejaski-Bosnjak V, Hollody K, et al. MRI

classification system (MRICS) for children with cerebral palsy:

Development, reliability, and recommendations. Dev Med Child

Neurol. 2017;59:57-64.

2. Appleton RE, Gupta R. Cerebral

palsy: Not always what it seems. Arch Dis Child.

2019;104:809-14.

3. Ginsberg L. Myelopathy: Chameleons

and mimics. Pract Neurol. 2017;17:6-12.

4. Jain VK.

Atlantoaxial dislocation. Neurol India. 2012;60:9-17.

5.

Lee W-H, Ko M-S. Effect of sleep posture on neck muscle

activity. J Phys Ther Sci. 2017;29:1021-4.

|

|

|

|

|