|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2017;54:

363-367 |

|

Probiotics for Promoting Feed Tolerance in

Very Low Birth Weight Neonates ó A Randomized Controlled

Trial

|

|

A Shashidhar, PN Suman Rao, Saudamini Nesargi,

Swarnarekha Bhat and BS Chandrakala

From Department of Neonatology, St Johnís Medical

College, Bangalore, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Shashidhar A, Assistant

Professor, Department of Neonatology, St. Johnís Medical College,

Sarjapur Road, Bangalore 34, Karnataka, India.

Email: [email protected]

Received: June 09, 2016;

Initial review: October 14, 2016;

Accepted: February 11, 2017.

Published online:

March 29, 2017.

Trial Registration: CTRI/2012/08/002853.

PII: S097475591600053

|

Objective: To measure the efficacy of a probiotic formulation on

time to reach full enteral feeds in VLBW (very low birth weight)

newborns.

Design: Blinded randomized

control trial.

Setting: A tertiary care neonatal

intensive care unit (NICU) in Southern India between August 2012 to

November 2013.

Participants: 104 newborns

with a birth weight of 750-1499 g on enteral feeds.

Intervention: Probiotic group (n=52)

received a multicomponent probiotic formulation of Lactobacillus

acidophilus, Lactobacillus rhamnosus, Bifidobacterium longum and

Saccharomyces boulardii once a day at a dose of 1.25◊109 CFU from

the time of initiation of enteral feeds till discharge and the control

group (n=52) received only breast milk.

Outcome measure: Time to reach

full enteral feeds (150 mL/kg/day).

Results: The mean (SD) time to

reach full enteral feeding was 11.2 (8.3) days in probiotic vs.

12.7 (8.9) in no probiotic group; (P=0.4), and was not

significantly different between the two study groups. There was a trend

towards lower necrotizing enterocolitis in the probiotic group (4% vs.

12%).

Conclusion: Probiotic

supplementation does not seem to result in significant improvement of

feed tolerance in VLBW newborns.

Keywords: Bifidobacterium, Infant feeding,

Lactobacillus, Necrotizing entrocolitis.

|

|

Enteral feeding intolerance is

a major issue in

premature infants, resulting in prolonged

hospitalization and a predisposition to serious

complications due to prolonged use of parenteral nutrition. A delay in

reaching full enteral feedings is also associated with a poorer mental

outcome in preterm neonates at 24 months corrected age [1].

As the maturation of motor activity in premature

infants lags behind that of digestive and absorptive functions, it is

most frequently a disorder of gastrointestinal motility that limits the

use of enteral feeding in this population. An adequate establishment of

the intestinal flora after birth is strictly related to motility

maturation and plays a crucial role in the development of gut barrier

function and the innate and adaptive immune system [2].

Enteral supplementation of probiotics prevents severe

necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) and all-cause mortality in preterm

infants [3]. Moreover, among the many strategies tried for prevention of

feeding intolerance, probiotics are the most promising. However, they

are yet to be used as standard of care. The objective of this trial was

to determine the efficacy of probiotics on feed tolerance in very low

birthweight (VLBW) neonates.

Methods

All neonates with a birth weight between 750 g to

1499 g admitted to the NICU in whom enteral feeds were started were

eligible for enrolment. Neonates with gastro-intestinal anomalies,

severe congenital malformation, and those not started on enteral feeds

by day 14 of life were excluded. The study was a double blind randomized

controlled trial (RCT) conducted in a tertiary care NICU between

August 2012 to November 2013.

We hypothesized that by establishing a normal

intestinal flora probiotics could reduce the incidence of feed

intolerance. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics

Committee and a written informed consent was taken from the

parent/guardian before enrollment.

Outcomes: The primary outcome of the study

was the time taken to reach full enteral feeds. Secondary outcomes were

episodes of feed intolerance, incidence of NEC stage 2 or more,

duration of hospital stay, days on total parenteral nutrition (TPN),

weight gain and mortality during hospital stay.

Feed intolerance was defined as presence of any one

of the following four features - abdominal distension

≥2 cm from the

previous measurement; or vomiting ≥2

episodes in the past 6 hours or blood stained or bilious; or gastric

aspirate >2 episodes of voluminous gastric aspirates in a 6 hr period.

Voluminous gastric residuals were defined as >50% of previous feed

volume if ≥6

mL/feed; or 2 episodes of >50% in a 6 hr period or single residue of

100% if feed volume <6 mL/feed.

Sample size: The sample size was determined based

on data from a pilot study done in the same clinical unit. To achieve a

significant mean difference of 3.37 days (with SD 5.05 and 6.6 in the 2

groups) in time to reach full feeds with a Type 1 error of 5% and a

Power of 80% (2 sided), the sample size required was 47 (in each group)

which was inflated by a further 10% based on the usual percentage of

deaths and discharges against medical advice in the VLBW group in our

Unit.

The subjects were randomly allocated into two groups

using computer generated random numbers by an investigator not directly

involved in the study. We followed a parallel group design and block

randomization was done with block sizes varying from 8 to 12.

Sequentially numbered opaque sealed envelopes were used for allocation

concealment. The two groups were coded as A and B and the group code was

kept off site in an opaque sealed envelope and opened only after the

final analysis was done.

Feeding protocol: Feeding was initiated,

advanced, stopped and restarted as per unit protocol derived by

consensus for the purpose of the study. The protocol was attached to all

the study case files to ensure compliance. Trophic feeds i.e 10

to 20 mL/kg/day at 2 hourly interval of either colostrum (if available)

or donor breast milk feeds were initiated in hemodynamically stable

infants. Feeds were advanced by 20 mL/kg/day (in babies 750-1249 g and

those with abnormal antenatal Doppler) or by 35mL/kg/day (in babies

1250-1499g and well). Feeds were given every 2 hourly and pre-feed

aspirates were measured in babies on gavage feeds. Feeds were withheld

if there were signs of feed intolerance, hemodynamic instability,

suspected NEC or voluminous gastric residuals. Feeds were restarted when

all the above mentioned signs were resolved. Parenteral nutrition was

continued till 100 mL/kg/day of feeds were reached. Full feeds were

defined as 150 mL/kg/day. Oral feeds were initiated in babies more than

30-32 weeks with good suck reflex and otherwise well. 5% Dextrose was

used if milk was not available. Human milk fortifiers were used as per

NNF India recommendations.

The weights were checked daily on a calibrated

digital weighing machine with a sensitivity of Ī5 g. A best gestational

age was given for each infant based on LMP and corroborated by early

first trimester ultrasound when available. NEC was defined and staged as

per modified Bellís staging. The infants were discharged as per unit

protocol which is baby maintaining hemodynamic stability without

support, on full oral feeds-either by breast milk or paladay, showing

consistent weight gain of 15 to 20 g/kg/day for 3 days and 1.4 kg or

more. The management protocols, clinical practices, equipment,

infrastructure, and key personnel were unchanged during the study

period. The baseline illness severity documented by Score for Neonatal

Acute Physiology Perinatal extension (SNAPPE-II) was used in both groups

[4]. Adequate antenatal steroids were defined as an interval of at least

24 hrs after the initial dose.

Probiotic group received a multicomponent probiotic

formulation of Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus rhamnosus,

Bifidobacterium longum and Saccharomyces boulardii in the

form of powdered sachets of 1g each (Darolac; Aristo Pharmaceuticals

Pvt. Ltd.). The intervention was administered once a day at a dose of

1.25◊10 9 CFU starting within

24 hours of initiation of feeds. It was given as a powder form dissolved

in breast milk and from day 2, given at a fixed time of the day. Fresh

suspensions of supplements were individually prepared in the pantry

under strict asepsis by study nurses who were not directly involved in

routine patient care for each study infant. The probiotic

supplementation was continued till discharge given once a day if the

volume of feeds was 2 mL or more, and in two divided doses if the baby

received <2 mL/feed. It was stopped when feeds were withheld for any

reason. The no probiotic group received only breast milk and served as

the control. No placebo was used.

The probiotic supplementation did not change the

physical appearance of the milk, and the syringes were labeled only with

the patientís name and identification number with no indication of study

group assignment. Attending physicians and nurses caring for the infants

were blinded to the group assignments. To ensure blinding, the mixing

was done after the milk required for each study infant was gathered away

from the patient care area in the NICU irrespective of the assigned

group. The probiotic was stored as per manufacturerís guidelines and was

prescribed to all infants enrolled in the study to ensure blinding.

Nurses followed strict asepsis during preparation and

compliance was monitored regularly by one of the investigators. The

infants were clinically monitored daily by the consultants for feed

intolerance and sepsis. A septic screen followed by blood culture was

done as per clinical suspicion.

Statistical analysis: Continuous variables were

compared by using Studentís t test or the Mann-Whitney U test when

appropriate; chi square analysis or Fisherís exact test when

appropriate, was used to ascertain significant differences in

categorical variables between groups. All tests were 2-tailed.

Significance was defined as P<0.05. Intention to treat analysis of data

was performed. The final statistical analysis was performed using SPSS

20.0 software (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA)

Results

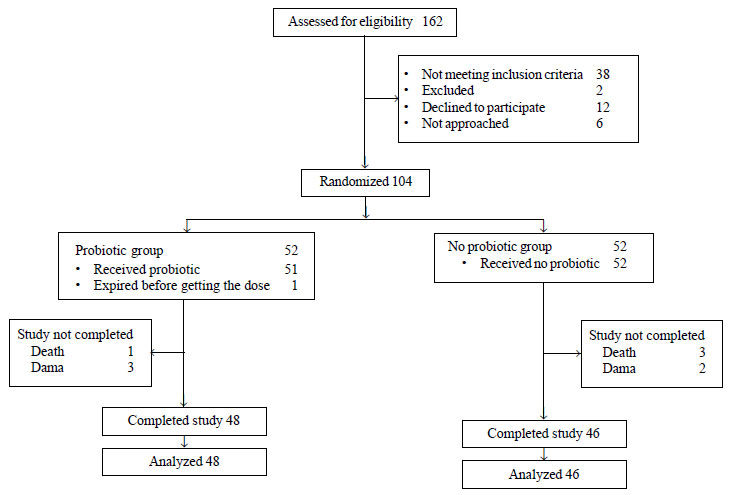

Of the 162 VLBW babies admitted to the NICU during

the study period, 104 VLBW newborns were enrolled; 52 in each group.

Fig. 1 shows the flow of study subjects through the phases of

the study.

|

|

Fig. 1 Trial flow.

|

The baseline characteristics are depicted in

Table I. The groups were comparable except for slightly more

number of Caesarean deliveries in the no probiotic group (Table

I). There were 5 extremely preterm babies (4 in control and 1 in

probiotic group) and 15 extremely low birth weight babies (10 in control

and 5 in probiotic group). Enteral feeding was initiated at a similar

postnatal age in the probiotic and no probiotic groups. Oral

supplementation with probiotics began in parallel with enteral feeding

(<24 h after initiation of feeds). A mean duration of 26.3 (17.6) days

of probiotic supplementation was received in the intervention group. 22

babies in the probiotic group and 25 in the control group were

exclusively fed with breast milk.

TABLE I Baseline Characteristics of Participants

|

Characteristics |

Probiotic (n=52) |

No probiotic (n=52) |

|

Gestational age *(wk) |

31.2 (2.1) |

31 (2.1) |

|

Sex (M:F) |

27:25 |

20:32 |

|

Birth weight *(g) |

1256 (185) |

1190 (208) |

|

Out born, n (%) |

10 (19.2) |

8 (15.3) |

|

Primigravida, n (%) |

30 (57.6) |

31 (59.6) |

|

Small for gestation, n (%) |

18 (34.6) |

19 (36.5) |

|

Gestational hypertension, n (%) |

21 (40.3) |

31 (59.6) |

|

Abnormal doppler, n (%) |

12 (23) |

9 (17.3) |

|

SNAPPE score* |

6.7 (7.9) |

8.3 (9.9) |

|

Caesarean delivery, n (%) |

27 (51.9) |

38 (73) |

|

Adequate antenatal steroids, n (%) |

27 (51.9) |

27 (51.9) |

|

APGAR at 1 min* |

6.6 (2.6) {n= 45} |

6.7 (1.5) {n= 46} |

|

APGAR at 5 min* |

8 (0.8) {n= 45} |

8 (1.0) {n= 46} |

|

Age at initiation of enteral feeds# (hrs.) |

15 (6,51) |

17 (9,47.5) |

|

*Mean (SD); #Median (IQR). |

The primary outcome of time to full enteral feeding

was 11.2 (8.3) days in probiotic vs 12.7 (8.9) in no probiotic

group and was not significantly different (Table II). The

secondary outcomes were also comparable between the groups. Treatments

such as duration of ventilation and antibiotic usage, and other co

morbidities like intraventricular hemorrhage, patent ductus arteriosus,

respiratory distress syndrome and bronchopulmonary dysplasia were not

significantly different between the two groups.

TABLE II Outcomes in Preterms in Probiotic and Control Groups

|

Parameter |

Probiotic group |

No probiotic group |

Mean difference

|

P

|

|

(n=48) |

(n=48) |

(95% CI) |

value |

|

Time to reach full feeds in days1 |

11.2 (8.3) |

12.7 (8.9) |

-1.5 (-4.9,1.9)

|

0.4 |

|

Duration of hospital stay (days)* |

27.6 (18.5) |

31.2 (22.9) |

-3.6 (-11.7,4.5) |

0.4 |

|

Duration of total parenteral nutrition (days)* |

9.5 (8.3) |

10.5 (9) |

-1.0 (-4.4,2.4) |

0.5 |

|

Number of episodes of feed intolerance# |

1 (0,2) |

1(0,2) |

0 (0.7,0.7) |

1.0 |

|

Number of withheld feeds# |

21 (1,40.5) |

12 (0,48) |

2.7 (-14.7,20) |

0.8 |

|

Weight gain per week (g)* |

31.1(27) |

39.5 (32.3) |

-8.4 (-20,3.2) |

0.2 |

|

Necrotizing enterocolitis ≥stage

II (%) |

2 (4.1) |

6 (12.5) |

3 (0.6,14.2)$ |

0.3 |

|

Mortality, n (%) |

1(1.9) |

3 (5.7) |

3 (0.3,27.9)$ |

0.6 |

|

*Mean(SD); #Median (IQR); $Relative risk

(95% CI). |

No unexpected adverse events were observed during the

course of the study. There was no significant difference in the

incidence of nosocomial infection, including fungal sepsis, in the

probiotic group.

Discussion

The present RCT comparing use of probiotic versus

no probiotic did not observe any significant reduction in the time

to reach full enteral feeding. However, VLBW infants receiving

probiotics reached full feeds 1.5 days earlier, which was similar to the

result of recently published systematic review [9].

The strength of the study was the blinding used. We

did not evaluate the successful colonization of infantsí gut by the

organism. The sample size derived from our pilot study was probably

over-optimistic on the expected effect size, as the difference observed

was much smaller.

The results of our study were similar to other

studies [6-12]. The RCTs which have shown a positive effect on time to

full feeds are the ones from India [13] and France [6]. However, the

Indian study enrolled infants at 5 days and allocation concealment, and

blinding of intervention and outcome was not adequately described [14],

and the French study [6]

showed a benefit only in >1000 g babies. In our

RCT, feeds were initiated at a median of 15 and 17 hours, respectively,

in the probiotic and no probiotic group which was comparatively early

compared to other RCTs which report a mean of about 3 to 5 days. Though

many trials and the Cochrane review [14] have shown a favorable impact

on time to reach full feeds with probiotics, i.e. three days

earlier than the control group (95% CI: 2.78 to 3.69 days, P<0.001),

many recent trials cited earlier have shown no improvement. The

guidelines for use of probiotics have been published [15] a few months

after initiation of our study. However, on review, our methodology was

consistent with most of the recommendations. There could be several

explanations for the observed results. It could be because of

predominant use of human breast milk in our NICU which is a rich natural

source of probiotic organisms and protects against NEC [16]. Most

studies showing benefit in NEC have had a significant use of non-human

milk. The second reason could be cross-contamination resulting in

nosocomial acquisition of probiotic strains by the other group in the

unit as evidenced by Kitajima [17] resulting in narrowing of differences

between the two groups. Cross-contamination in the control arm is

expected to underestimate the true effects of probiotics. A

significantly higher number of caesarean deliveries in the no probiotic

group (52% vs 73%) could have narrowed the differences. The

intestinal flora of caesarean delivered infants is altered and

characterized by a substantial absence of Bifidobacteria sp., and

vaginally delivered is characterized by predominant groups such as B.

longum and B. catenulatum. Therefore, the infants who would

have probably benefited more by probiotics were in the control arm. It

may also be due to the different strains used in our study which were

chosen on the basis of availability and existing literature of the time.

In conclusion, in the present double-blind randomized

trial, oral supplementation with multicomponent probiotic formulation of

L. acidophilus, L. rhamnosus, B.longum and S. boulardii

did not improve the gastrointestinal tolerance to enteral feeding in

very-low-birth weight infants, but was a safe intervention. We suggest

larger multicentric trials of probiotic supplementation to achieve early

feed tolerance before accepting/rejecting probiotics for wider clinical

use.

Acknowledgements: Nursing staff of the St

Johnís Medical College NICU for their invaluable help in this research,

parents of the infants who took part in this study, Dr.Tinku Sarah for

helping with the statistical analysis.

Contributorsí: SA: conceptualized and

designed the study, drafted the initial manuscript, and approved the

final manuscript as submitted; SR, SB: reviewed and revised the

manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted; SN, CBS:

designed the data collection instruments, and coordinated and supervised

data collection.

Funding: None; Competing interest: None

stated.

References

1. Morris BH, Miller-Loncar CL, Landry SH, Smith KE,

Swank PR, Denson SE. Feeding, medical factors, and developmental outcome

in premature infants. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1999;38:451-7.

2. Indrio F, Riezzo G, Cavallo L, Mauro A Di,

Francavilla R. Physiological basis of food intolerance in VLBW. J Matern

Neonatal Med. 2011;24:64-6.

3. Patole S. Nutrition for the Preterm Neonate - A

Clinical Perspective. Springer, Nether Lands; 2013.

4. Richardson DK, Corcoran JD, Escobar GJ, Lee SK.

SNAP-II and SNAPPE-II: Simplified newborn illness severity and mortality

risk scores. J Pediatr. 2001;138:92-100.

5. Athalye-Jape G, Deshpande G, Rao S, Patole S.

Benefits of probiotics on enteral nutrition in preterm neonates: a

systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100:1508-19.

6. Rouge C, Piloquet H, Butel MJ, Berger B, Rochat F,

Ferraris L, et al. Oral supplementation with probiotics in

very-low-birth-weight preterm infants: A randomized, double-blind,

placebo-controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:1828-35.

7. Mihatsch WA, Vossbeck S, Eikmanns B, Hoegel J,

Pohlandt F. Effect of Bifidobacterium lactis on the incidence of

nosocomial infections in very-low-birth-weight infants: a randomized

controlled trial. Neonatology. 2010;98:156-63.

8. Manzoni P, Mostert M, Leonessa ML, Priolo C,

Farina D, Monetti C, et al. Oral supplementation with

Lactobacillus casei subspecies rhamnosus prevents enteric colonization

by Candida species in preterm neonates: A randomized study. Clin Infect

Dis. 2006;42:1735-42.

9. Lin H-C, Hsu C-H, Chen H-L, Chung M-Y, Hsu J-F,

Lien R, et al. Oral probiotics prevent necrotizing enterocolitis

in very low birth weight preterm infants: a multicenter, randomized,

controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2008;122: 693-700.

10. Fernandez-Carrocera LA Cabanillas-Ayon M,

Gallardo-Sarmiento RB, Garcia-Perez CS, Montano-Rodriguez R, Echaniz-Aviles

MO S-HA. Double-blind, randomised clinical assay to evaluate the

efficacy of probiotics in preterm newborns weighing less than 1500 g in

the prevention of necrotising enterocolitis. Arch Dis Child. Fetal

Neonatal Ed. 2013;98:F5-9.

11. Braga TD, da Silva GAP, de Lira PIC, de Carvalho

Lima M. Efficacy of Bifidobacterium breve and Lactobacillus casei oral

supplementation on necrotizing enterocolitis in very-low-birth-weight

preterm infants: a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Am J Clin

Nutr. 2011;93:81-6.

12. Bin-Nun A, Bromiker R, Wilschanski M, Kaplan M,

Rudensky B, Caplan M, et al. Oral probiotics prevent necrotizing

enterocolitis in very low birth weight neonates. J Pediatr.

2005;147:192-6.

13. Samanta M, Sarkar M, Ghosh P, Ghosh J kr, Sinha

MK, Chatterjee S. Prophylactic probiotics for prevention of necrotizing

enterocolitis in very low birth weight newborns. J Trop Pediatr.

2009;55:128-31.

14. Alfaleh K, Anabrees J, Bassler D, Al-Kharfi T.

Probiotics for prevention of necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm

infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;3:CD005496.

15. Deshpande GC, Rao SC, Keil AD, Patole SK.

Evidence-based guidelines for use of probiotics in preterm neonates. BMC

Med . 2011;9:92.

16. Lucas A., Cole TJ. Breast milk and neonatal

necrotising enterocolitis. Lancet. 1990;336:1519-23.

17. Kitajima H, Sumida Y, Tanaka R, Yuki N, Takayama

H, Fujimura M. Early administration of Bifidobacterium breve to preterm

infants: randomised controlled trial. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed.

1997;76:F101-7.

|

|

|

|

|