edical schools came into being with the purpose

of generating a scientifically trained professional workforce for

serving the health needs of the society. Over the years, a perceptibly

increasing gap between the health professionals’ education, health care

delivered, and societal health needs has raised global concerns [1,2].

Medical schools are increasingly facing the question, ‘Are they

producing graduates who are competent to cater to health needs of the

society?’ – Perhaps, not in entirety. For any corrective action;

therefore, it is only befitting that we re-trace and work our way

backwards from first defining the expected roles of a physician that

best serve the healthcare requirements of the community (local and

global) and also to clearly state the characteristics and abilities of

doctors graduating from medical schools that enable them to perform

these roles well [3]. The curricula then need to be designed towards

achieving these outcome requirements steered by appropriate assessment

methods. Herein lies the origin and essence of Competency-based Medical

Education (CBME).

The goal of Undergraduate (UG) medical training is to

produce ‘doctors of first contact’ or ‘primary care physicians’. Having

stated this goal, most traditional curricula and training programs,

including those in Indian institutions, have been designed around the

educational/ learning objectives [2]. These objectives largely allude to

knowledge base with some reference to procedural skills, and behavior to

be developed during the course of training. The holistic description of

the outcome product of a medical school viz, the array of

abilities of a fresh graduate, so as to perform the expected roles in

providing health care to the community` has been lacking. Accordingly,

assessment methods also were traditionally designed to measure

attainment of knowledge or specific skills rather than the ability of

the graduate in delivering judicious and contextual health care in

authentic settings.

Awakened to this misalignment of training and needs,

the efforts at making the ‘competencies’ as the chief driving force of

medical training and curricular planning has gained momentum since the

turn of the century [1,2,4]. In this article we discuss the concept of

competency-based medical education in comparison to the traditional

curricula in the Indian perspective, and also its implementation,

particularly the assessment for such a medical training.

Definitions

The dictionary meaning of the terms ‘competency’ or

‘competence’ is "ability to do something" or "ability for a task". While

the two terms are used interchangeably, competencies may also be viewed

as ingredients of competence i.e., many specific competencies in

combination constitute a broader area of competence [5]. Competence in a

particular area encompasses many aspects and hence is best expressed as

a description (statement) of abilities in context of setting, experience

and time (or stage of training) [5-7].

A comprehensive and widely cited definition of

Professional competence as proposed by Epstein and Hundert in 2002,

states: "the habitual and judicious use of communication, knowledge,

technical skills, clinical reasoning, emotions, values, and reflection

in daily practice for the benefit of the individual and community being

served" [4].

With evolving understanding and increasing consensus

on the issue, a definition of Competency-based Education as proposed by

Frank, et. al. in 2010, makes the core purpose and curricular

elements of CBME more lucid: "Competency-based education (CBE) is an

approach to preparing physicians for practice that is fundamentally

oriented to graduate outcome abilities and organized around competencies

derived from an analysis of societal and patient needs. It de-emphasizes

time-based training and promises greater accountability, flexibility,

and learner-centeredness" [8]. Some experts consider CBME as another

form of outcome-based education (OBE), where learning outcomes assume

more importance than learning pathways or processes.

Global Movement Towards Competency-based Medical

Education

Competencies are context-dependent and hence are

contextually expressed and communicated. This has resulted in various

competency frameworks in use in different countries/regions. Also,

within the same country, these frameworks have undergone modifications

and refinements over time.

In United States, the Outcome Project was initiated

by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) in

2001 for emphasizing the ‘educational outcomes’ in terms of competencies

to be achieved during the course of training [9,10]. These competencies

were identified under six domains, also referred to as general

competencies, for all physicians irrespective of specialty. These are:

Medical Knowledge, Patient care, Interpersonal and Communication skills,

Professionalism, Practice-based learning and improvement, and

System-based practice. They provided a framework for education and

evaluation by specifying the end product rather than the desired

training process or pathway. As a refinement measure towards assessment

and defining the training pathway the ACGME launched the ‘Milestones

Project’ in 2007 [7,11]. Thus sub-competencies, that serve as

‘milestones’ along the way to becoming fully competent, and hence must

be achieved during the course of training were specified for each

outcome competency [9].

In United Kingdom, the General Medical Council

defined the outcomes and standards of graduate medical education, and

brought out the details of competency framework in form of the document

‘Tomorrow’s Doctors’ in 1993, that underwent further refinements over

time [12]. Three broad outcomes were specified for medical graduates: (i)

Doctor as a scholar and a scientist, (ii) Doctor as a

practitioner, and (iii) Doctor as a researcher. Under each of

these heads, sub competencies were further specified. The standards of

teaching learning and assessment were further grouped under nine

domains. For each domain, the standards, the criteria and the evidence

(for evaluation) were specified in concrete terms [12].

The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of

Canada (RCPSC) expressed the outcome of undergraduate medical training

in terms of seven ‘roles’ of a physician and developed competency

framework based on these – the Canadian Medical Education Directions for

Specialists (CanMEDS) [13]. These roles were: medical expert,

communicator, collaborator, manager, health advocate, scholar and

professional.

The National Undergraduate Framework in Netherlands

is yet another example of a well implemented outcome competency-based

medical education framework [3]. Medical educationists from the

Netherlands further propose that competencies are perhaps better

observed and measured as Entrustable Professional activities (EPA),

discussed later in the article [14]. An effort at defining outcomes has

also been noted from Vietnam, Mexico and China [15].

Comparison With Traditional Curriculum

A comparative analysis of traditional

discipline-based curriculum and competency-based curriculum is provided

in Web Table I [2,3,5,14,16-18]. However, this analysis

should not lead us to believe that one approach should completely

replace the other. Incorporating elements of competency-based training

utilizing the systems approach, and retaining the strengths of the

traditional curricula would be desirable. This would certainly be a

challenging task.

The three key steps in planning a competency-based

curriculum, as suggested by experts and utilized by institutions running

such programs [5,19-22] are:

1. Identification of competencies

2. Content identification and program

organization

3. Assessment planning and program evaluation

For implementation, they can be further divided into

component steps and strategies as shown in Table I.

Additionally, faculty development and creating conducive environment is

a must for effective delivery of the curriculum.

TABLE I Steps of Competency-based Curriculum Planning and Strategies for Implementation

|

Steps for planning Competency-based Curriculum |

Steps and strategies for implementation |

|

I |

Identification of competencies |

• |

Competency identification by consensus opinion of experts,

health needs, analysis of physician activities, self-report by

physicians to identify critical elements of behavior, critical

incidents, public health statistics, medical records, practice

setting and resources. |

|

|

• |

Exactly define required competencies and their components: Bring

out statement of learning outcomes and communicate to faculty

and students |

|

II |

Content identification & Program organization |

• |

Identify corresponding course content |

|

|

• |

Course organization: sequencing, learning opportunities, select

educational activities, experiences and instructional methods |

|

|

• |

Time organization: delineate minimum and maximum time period of

training; Create space for feedback sessions and opportunity to

reflect. |

|

|

• |

Define the desired level of mastery/expertise in each area |

|

|

• |

Define milestones or achievement points along development path

for competency i.e. charting of student progression pathway. |

|

III |

Assessment planning and Program evaluation |

• |

Identify observable and measurable form of competencies in real

settings; e.g. EPA |

|

|

• |

Define performance criteria: Establish minimum acceptable norms

of summative performance and intervening levels of expertise. |

|

|

• |

Select assessment tools to measure progress along the charted

pathways i.e. formative assessment for achievement of milestones |

|

|

• |

Develop a longitudinal assessment program (rather than

standalone formative and summative assessments), with emphasis

on WPBA methods: Make a blueprint with areas to be assessed,

timing and assessors |

|

|

• |

Design an outcomes evaluation program with scope for curricular

review and improvement |

|

|

• |

Faculty development and student orientation |

|

|

• |

Ensuring conducive educational environment |

|

|

• |

Student selection: incorporate some mechanism for assessing

aptitude and motivation towards pursuing medical studies and

delivering health care |

For program organization and assessment planning, it

is important to remember that the competencies are developmental, i.e.,

expertise in a said area progressively changes over time and with

experience. This has two implications: first, attainment of a competency

can be viewed as passing through intermediate levels of expertise in

various aspects of that competency, to be achieved (corresponding to the

stage of learning) during the course of becoming fully competent – akin

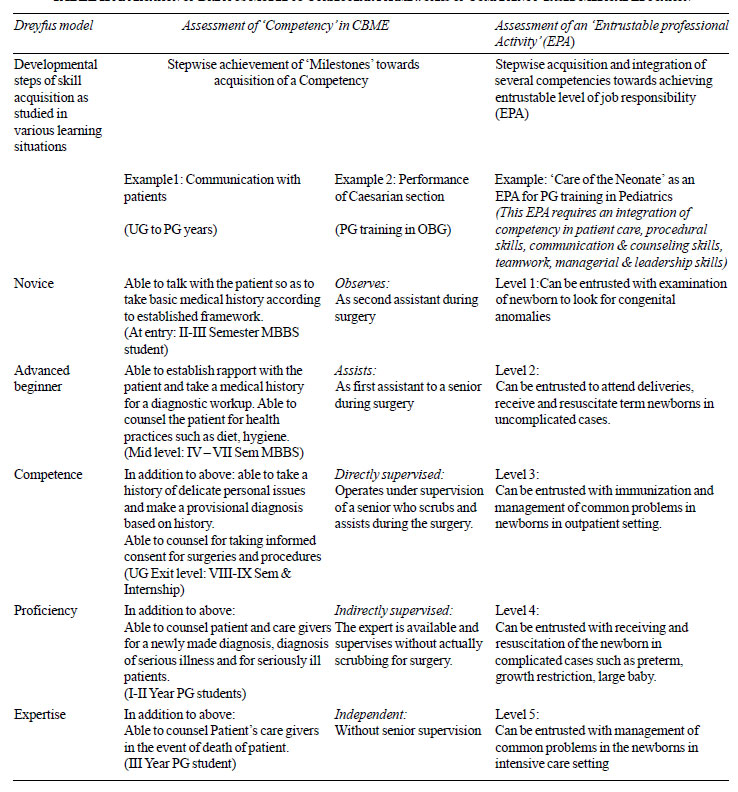

to the rungs of a ladder. Dreyfus and Dreyfus proposed a model of

phase-wise learning with developmental stages of skill acquisition, the

stages being Novice, Advanced beginner, Competence, Proficiency and

Expertise [23,24]. This model can also be applied to medical education

as illustrated in Table II. These meaningful achievement

points that mark the attainment of a predefined performance level during

the learning phase have been given different labels, e.g., the

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), USA,

refers to these as ‘Milestones’ to be achieved on way towards becoming

fully competent [7,25].

|

TABLE II Application of Dreyfus Model to

Curricular Frameworks of Competency-based Medical Education

|

|

The second consequence is, that a level of expertise

for being called ‘fully competent’ needs to be specified. This cut-off

is not set at the minimum level of expertise but at a level when the

person can act independently and take responsibility for his action or

performance in that area. Therefore, it is rightly said that the

ultimate goal in CBME is not merely attainment of competency but an

expertise (specified) in the area [16]. These two aspects are an

important consideration in designing the formative and summative

assessment in competency-based education.

Assessment in CBME

Some pertinent issues with regards to assessment in

CBME are discussed below:

What to assess?

In CBME, the outcome is expressed in terms of

competencies. Medical education literature distinguishes between the

terms ‘competence’ (meaning ‘able to do’) and ‘performance’ (meaning

‘actually does’). According to Miller’s pyramid model of clinical

competence, the assessment of performance is at the highest level

i.e. the ‘Does’ ; and competence assessment is a level below i.e

‘Shows how’. Naturally, performance assessment provides a more authentic

picture of trainees’ functionality in real clinical settings [17]. While

competence can be assessed in examination setting using simulations and

with tools such as Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE), it

can perhaps be better inferred from observable workplace performance

using Workplace-based Assessment (WPBA) tools [18] .

What to Measure While Assessing?

Assessment requires identification of measurable and

observable entities. This could be in the form of whole tasks that

contribute to one or more competencies or assessment of a competency

per se. While it appears reasonably justifiable to work on this

framework, there have been concerns that attaining individual

competencies may not actually lead to actual or acceptable performance.

A trainee who is competent in history taking, physical examination and

treatment planning, may still be unable to actually treat a patient. In

this context, the concept of ‘Entrustable Professional Activity’ (EPA)

[6] makes a lot of sense.

The EPA encompasses a set of professional work

activities that together constitute the particular profession or

specialization. Only after mastering a certain set of competencies can a

trainee be entrusted with carrying out a particular professional

activity with responsibility [14,26]. Observing and measuring

competencies in form of EPA gives a more authentic information about the

ability of the trainee to function as a professional in real life

situation, and hence a better validity to assessment.

Let us try to illustrate this concept by using a

simple example. While teaching driving to a novice, we set certain

objectives for ourselves. For example, he ‘should be able to start the

engine’, ‘change the gears’, and ‘coordinate the release of clutch and

accelerator’ and so on. Attainment of these does not mean that he will

be able to drive a car. However, if we change our outcome to ‘competent

to drive a car’ then this problem can be avoided and we will continue

our training till the trainee is able to drive a car. When the trainee

demonstrates his ability to drive a car, we can call him competent.

However, there may be more issues to it. He may be able to drive a small

car but not a large one or he may be able to drive a car in a small town

but not in the traffic of a metropolis or not in a hilly terrain. We may

entrust a trainee driver to drive us in a small town with not much of

traffic but need to provide more training before we can entrust him to

drive us in a metro. On the same analogy, we have different levels of

trust on the trainees depending upon their degree of expertise, stage of

training and context of performance. The concept of EPA will be further

discussed in detail in our next article in this series.

In our day-to-day practice, we all entrust night on-

call residents with different levels of tasks – we depend on someone to

be able to decide on what samples to collect but may not depend on

him/her to make the choice of an antibiotic. EPAs help us to decide the

level of trust we can place on a trainee to independently handle a given

task.

It is also easier to observe and judge the

proficiency with which a certain job activity is performed rather than

trying to observe and measure each competency contributing to it. The

term ‘entrustable’ in EPA inherently conveys the minimum acceptable

standard i.e., the trainee is able to carry out the said clinical

activity independently, can take responsibility for the same and hence

can be entrusted with it. Ten Cate proposed that once the EPA is of an

acceptable standard, a written statement to this effect may be issued to

the trainee: a Statement of awarded responsibility (STAR) [14].

Assessment of EPA may have a relatively more meaningful and utilitarian

interpretation, especially in formative assessments.

Also, it is of extreme importance to define standards

of measurement of sub-competencies (e.g., Milestones or

benchmarks; Levels of EPA) to be achieved at various stages of training.

This charts out the desired pathway to becoming fully competent.

Examples of developmental phases of attainment of competency and

entrustment of professional activity, based on Dreyfus model are shown

in Table II. Though the framework of EPA appears more

suitable for Postgraduate training, it may also by utilized for

Undergraduate medical training thus providing a developmental continuum

to specialist training [27] The next paper in this series of medical

education articles is dedicated to a full discussion on EPA.

How to Measure: the Methods, Tools and Reporting

Since CBME focuses on the outcome, it is important to

observe and assess (and learn) at workplace. Daily practice area

provides a richer source of information rather than isolated hand-picked

tasks in examination setting. The WPBA methods assess at the ‘does’

level of Miller’s pyramid and hence are most suitable [18]. These

include mini-Clinical Evaluation Exercise (mini-CEX), Directly Observed

Procedural Skills (DOPS), mini-Peer Assessment Tool (mini-PAT),

Multisource feedback (MSF) as some of the common ones. Each of the tools

can provide information about more than one competency; and any

competency can be assessed in a better way by using more than one tool

(triangulation). We have already discussed WPBA in detail in an earlier

paper [27].

Another aspect is the recording and reporting of

observations. There has been an undue emphasis on objectification of

assessment scores [16]. Subjective interpretations of assessment have

been underutilized and in fact been maligned to some extent. To some

extent, it has been so because subjectivity has been misinterpreted as

bias. This concern can be minimized by utilising multiple assessors over

multiple occasions and settings. Judgment by an expert can be well

expressed subjectively in words. It may in fact be more meaningful and

useful to the trainee than a set of scores or categories conveyed at the

end of assessment. This is particularly true for CBME since competencies

are developmental and their progression depends heavily on the

appropriate steering by assessment. The formative function of assessment

is served well by subjective reporting of assessment.

Recently, there is increasing emphasis on utilising

qualitative approach in assessment [16]. Use of student narratives and

portfolios can be a rich source of information about student learning.

Tekian, et al. [28] propose redefining of ‘competence’ itself in

terms of construct narratives rather than as a checklist of component

tasks.

Feedback: Whatever the assessment method, tool or

reporting format, it is of utmost importance to provide an early and

effective feedback to the trainee, preferably based on direct

observation. Development of competencies hinges on the feedback received

by the student trainee so that student progresses through the charted

milestones. There is evidence in literature that establishes feedback as

the most important determinant of learner progression [16].

When to Assess?

Frequent (or continuous) formative assessments that

allow for and promote developmental progression are desirable in CBME.

This helps to keep the trainee on the correct trajectory towards end

outcomes [18]. Hence there is a greater emphasis on formative assessment

in CBME.

Who Should Assess?

Faculty, peers, colleagues may assess depending on

the competency being assessed. It is more important that the assessors

are trained in using the method and tools that they use. Inter-rater

variation in assessment can be reduced by assessor training as well as

defining the standards for expected outcomes.

Standards of Assessment in CBME

It is well expressed by educationists that expertise

and not competence is the ultimate goal in CBME [16]. The standards of

acceptable level of expertise must be well- defined in competency-based

training programs, and these must be defined not just for the outcome-

competencies but also for the intervening milestones to be achieved by

the trainee. While establishing cut off standards, it is important to

adopt a criterion-based approach [16,17]. That is, the set standard is

an absolute level of performance (or competence) and is not dependent on

the performance of other students. Adopting a normative-approach has the

inherent risk that the standards may be set below acceptable level of

expertise.

CBME: The Indian Scenario

In India, there has been a relatively recent

need-driven movement towards competency based medical education, and it

is yet in a fledgling stage of discussions and planning. The Graduate

Medical Education Regulations 1997 (GMER) of the Medical Council of

India (MCI) mention the term ‘competent’ under institutional goals but

do not define it further [29]. Following a series of meetings and

deliberations, reforms were suggested in the form of ‘Vision 2015’

document in 2011 [30]. For the first time, the outcomes of graduate

medical education were expressed as the competencies that an ‘Indian

Medical Graduate’ would develop so as to function as a ‘Basic Doctor’ or

physician of first contact to the people of India and the world. The

five roles of a Basic doctor were stated as: Clinician, Leader and team

member, Communicator, Lifelong learner, and Professional (who is

ethical, responsive and accountable to patients, community and

profession). The competencies to be developed to perform the above roles

were also specified. The term competency was meant to imply ‘desired and

observable ability in the real life situation’. Unfortunately, in these

deliberations, assessment was neither discussed in appropriate details

nor was an assessment program aligned to outcome- measurement included.

The document did mention in passing that assessment be ‘criterion

referenced’ without giving any further details.

Based on above deliberations and documents, the new

Graduate Medical Education Regulations 2012 (GMER 2012) were proposed

[31]. A salient feature of this revision of medical curriculum was

emphasis on competency-based curriculum. While subject-wise specific

outcome competencies were mentioned in this document, the alignment of

assessment towards measuring competencies again remained largely

unaddressed. The Postgraduate Medical Education Regulations 2000 (PGMER)

of the MCI merely mention that the PG curriculum be competency-based,

and that each department must produce statement of competencies [32].

Hence, we as a country still have a long road ahead

towards implementing competency-based medical training. There is a need

to review and revise our curriculum respecting the key role of

assessment in achieving the deliverables. With the benefit of the

existent curricular frameworks in use in different nations, we need to

develop a competency framework suited to our needs and feasible in our

settings and resources.

Faculty Development

Since the competency-based training program and

assessment methods differ in many ways from the traditional curricula,

it is important not only to orient the faculty to it but also to train

the faculty in using the appropriate assessment methods. Of particular

importance is the faculty training for improving the direct observation

skills and feedback skills.

Where We Stand and What Needs to be Done

As we move towards developing a competency-based

approach to medical education in our country, it is crucial to sensitize

and prepare the faculty for the change. An initial combined and

organized effort for identification of general competencies and

specialty competencies may be a good starting point. Assessment has a

key role in shaping the outcomes and success of a curriculum and hence

must be carefully planned.

1. Long DM. Competency-based residency training: The

next advance in Graduate Medical Education. Acad Med. 2000;75:1178-83.

2. Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, Cohen J, Crisp N,

Evans T, et al. Health professionals for a new century:

transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent

world. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2011;28:337-41.

3. Harris P, Snell L, Talbot M, Harden RM for the

International CBME Collaborators. Competency-based medical education:

implications for undergraduate programs. Med Teach. 2010;32:646-50.

4. Epstein RM, Hundert EM. Defining and assessing

professional competence. JAMA. 2002;287:226-35.

5. Frank JR, Snell LS, Cate OT, Holmboe ES, Carraccio

C, Swing SR, et al. Competency-based medical education: theory to

practice. Med Teach. 2010;32:638-45.

6. Englander R. Glossary of Competency-based

Education terms. Available from: http://dev.im.org/AcademicAffairs/milestones/Documents/CBME%20Glossary.pdf.

Accessed November 15, 2014.

7. Orgill BD, Simpson D. Towards a glossary of

competency-based medical education terms. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6:203-6.

8. Frank JR, Mungroo R, Ahmad Y, Wang M, De Rossi S,

Horsley T. Toward a definition of competency-based education in

medicine: a systematic review of published definitions. Med Teach.

2010;32:631-7.

9. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical

Education. ACGME Outcome Project enhancing residency education through

outcomes assessment: General Competencies. 1999. Available from:

http://www.acgme.org/outcome/comp/compFull.asp. Accessed November 9,

2014.

10. Joyce B. Introduction to Competency-based

education. Facilitators guide ACGME. 2006. Available from:

http://www.paeaonline.org/index.php?ht=a/GetDocument Action/i/161740.

Accessed December 27, 2014.

11. Weinberger SE, Pereira AG, Lobst WF, Mechaber AJ,

Bronze MS, Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine Education Redesign

Task Force II. Competency-based education and training in Internal

Medicine. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:751-6.

12. General Medical Council. Tomorrow’s Doctors:

Education Outcomes and standards for undergraduate medical education.

Available from:

http://www.gmcuk.org/Tomorrow_s_Doctors_0414.pdf_48905759.pdf.

Accessed December 27, 2014.

13. Frank JR, Danoff D. The CanMEDS Initiative:

implementing an outcomes-based framework of physician competencies. Med

Teach. 2007;29:642-7.

14. ten Cate O, Scheele F. Competency-based

Postgraduate training: Can we bridge the gap between theory and clinical

practice. Acad Med. 2007;82:542-7.

15. Harden RM. Outcome-based education – The future

is today. Med Teach. 2007;29:625-9.

16. Holmboe ES, Sherbino J, Long DM, Swing SR, Frank

JR, for the International CBME Collaborators. The role of assessment in

competency-based medical education. Med Teach. 2010;32:676-82.

17. van Mook WNKA, Bion J, van der Vleuten CPM,

Schuwirth LWT. Integrating education, training and assessment:

competency-based intensive care medicine training. Neth J Crit Care.

2011;15:192-8.

18. Boursikot K, Etheridge L, Zeryab S, Sturrock A,

Ker J, Smee S, Sambandam E. Performance in assessment: Consensus

statement and recommendations from the Ottawa conference. Med Teach.

2011;33:370-83.

19. Chacko TV. Moving towards competency-based

education: Challenges and the way forward. Arch Med Heath Sci.

2014;2:247-53.

20. McGaghie WC, Miller GE, Sajid AW, Telder TV.

Competency–based Curriculum Development in Medical Education. An

Introduction. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1978.

21. Harden RM. Outcome-based education – the ostrich,

the peacock and the beaver. Med Teach. 2007;29:666-71.

22. Smith SR, Dollase R. AMEE guide No. 14: Outcome-

based education Part 2 – Planning, implementing and evaluating a

competency–based curriculum. Med Teach. 1999;21:15-22.

23. Dreyfus HL, Dreyfus SE. Mind over Machine: The

Power of Human Intuition and Expertise in the Age of the Computer.

Oxford: Basil Blackwell; 1986.

24. Batalden P, Leach D, Swing S, Dreyfus H, Dreyfus

S. General competencies and accreditation in Graduate medical education.

Health Affairs. 2002;21:103-11.

25. Nasca TJ, Philibert I, Brigham T, Flynn TC. The

next GME accreditation system – rationale and benefits. New Eng J Med.

2012;366:1051-6.

26. van Loon KA, Driessen EW, Teunissen PW, Scheele

F. Experiences with EPAs, potential benefits and pitfalls. Med Teach.

2014;36:698-702.

27. Singh T, Modi JN. Workplace based assessment: A

step to promote competency based training. Indian Pediatr.

2013;50:553-9.

28. Tekian A, Hodges BD, Roberts TE, Schuwirth L,

Norcini J. Assessing competencies using milestones along the way. Med

Teach. 2014;19:1-4.

29. Medical Council of India Regulations on Graduate

Medical Education 1997. Available from:

http://www.mciindia.org/RulesandRegulations/GraduateMedicalEducation

Regulations1997.aspx. Accessed November 10, 2014.

30. Medical Council of India. Vision 2015. Medical

Council of India. New Delhi. 2011. Available from:

http://www.mciindia.org/tools/announcement/MCI_booklet.pdf.

Accessed November 10, 2014.

31. Medical Council of India Regulations on Graduate

Medical Education 2012. Available from:

http://www.mciindia.org/tools/announcement/Revised_GME_2012.pdf .

Accessed October 2, 2014.

32. Medical Council of India, Post Graduate Medical

Education Regulations 2000, Medical Council of India, New Delhi.

Available from:

http://www.mciindia.org/Rules-and-Regulation/Postgraduate-Medical-Education-Regulations-2000.pdf.

Accessed November 29, 2014.