|

Achieving optimal enteral feeding is crucial for

the growth of the newborn, and delay in establishing full enteral feed

is associated with adverse short term and long term outcomes [1].

Advancement of enteral nutrition in preterm neonates is hampered by

gastric residuals and feeding intolerance. Gastrointestinal hypomotility

and non-development of coordinated peristalsis are the postulated

reasons for feeding intolerance [2-5].

Various feeding strategies (like trophic feeding and

slow feeding advancement), medications (like antenatal steroids and

prokinetics), and meconium evacuation are used to improve feeding

intolerance [6-9]. Immature intestinal motor mechanism and

neurotransmitter system is considered to be responsible for delay in

passage of meconium in preterm infants. Retained thick tenacious

meconium leads to functional obstruction, abdominal distension, gastric

residuals and feeding intolerance [10-12]; and total meconium evacuation

may improve feeding volume [11,13,14]. We hypothesized that glycerin

suppository – by acting as osmotic laxative – will facilitate early

meconium evacuation and accelerate feed tolerance and advancement in

preterm very-low-birthweight (VLBW) neonates. Our specific objective was

to compare the efficacy of glycerin suppository versus no

glycerin suppository in preterm VLBW neonates on time required to

achieve full enteral feeds.

Methods

This randomized controlled trial was conducted in a

Level III neonatal unit in Mumbai, India from March 2010 to April 2011.

The study was approved by the hospital’s Academic research ethics

committee. Infants were enrolled after obtaining written informed

consent from parents or legal guardians.

Infants admitted to neonatal intensive care unikt

(NICU) on day-1 of life, with a birthweight between 1000 to 1500 grams,

and gestational age between 28 to 32 weeks were eligible for inclusion

in the study. Infants with gastrointestinal or other systemic

malformations were excluded. Infant with hemodynamic instability and

features of shock were also excluded.

Eligible neonates were randomized to either glycerin

suppository group or control group. Those in the glycerin suppository

group received the drug at a dose of one infant glycerin suppository (Hallens

Infant Glycerin Suppository 1g, Meridian

Enterprises) once a day from day-2 of life onwards. Those assigned to

control group were not given any suppository, only a sham procedure was

performed (no active placebo). Sequence was generated using random

allocation software in variable blocks of 2 or 4, by a statistician who

was not part of the study. Randomization allocation concealment was

achieved by creating sequentially numbered sealed opaque envelopes that

contained the randomization codes. When a patient meeting inclusion

criteria was admitted in the unit, doctor on duty obtained written

informed consent from parents. The serially numbered opaque sealed

envelope was opened by the designated study staff nurses. Access to

these envelopes was only limited to these designated study staff nurses.

Nursing staff involved in care of infant, on-duty resident doctors and

consultants involved in the care of infant were blinded to study

intervention. The glycerin suppository administration or sham procedure

was performed by designated study staff nurses (two) behind curtains.

This intervention was continued till day 14 of life irrespective of

passage of stools. Glycerin suppository or sham intervention was

withheld if there was hemodynamic instability. These two study nurses

were otherwise not involved in day-to-day clinical management of these

infants. Feeds were started in both groups of infants when they were

clinically stable, usually between 3rd

to 5th day of life. The

feeds were in the form of intermittent boluses every 2 hours through

orogastric infant feeding tube. All infants received either expressed

breast milk (EBM) and/or preterm infant milk formula (Lactodex LBW,

Raptakos, Brett and Co. Ltd.); EBM was preferred, if available. The

initial feeding volume was 20 mL/kg/day and the volume was increased

daily by 20 mL/kg/day, if tolerated until complete enteral feeding was

achieved (180 mL/Kg/day). Feeds were withheld if clinical signs and

symptoms suggestive of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) or other

intra-abdominal pathology were suspected. Feeding was withheld as per

clinical condition or if gastric residuals exceeded 20% of previous feed

volume. EBM was fortified with a commercial powder preparation (Lactodex

HMF, Raptakos, Brett and Co. Ltd) once full feeds were tolerated by

infant. Feeding policy was similar in both study groups.

Standards of care of infants in the NICU did not

change throughout the study period. Grading up of intravenous fluids,

parenteral nutrition and starting of trophic feeds was done as before as

per the standard protocol of the unit. The regimen of parenteral

nutrition used for both groups remained same and it consisted of

solution of 10% dextrose, amino acids and electrolytes. Parenteral

nutrition was started on day-2 of life in all infants and advanced daily

to meet each infant’s total estimated fluid and nutritional

requirements.

The primary outcome was time required by the infant

to achieve full enteral feeds. (when the infant tolerated a volume of

180 mL/kg/day for at least 24 hours). Secondary outcomes were: time

required to regain birth weight, age of achieving a weight of 1700

grams, necrotizing enterocolitis (Bell classification) [15], proportion

of infants in whom feeds were withheld for any reasons, and age at the

time of discharge from hospital. All infants were followed up till the

time of discharge from the hospital or transfer to other hospital. All

the data were recorded in predesigned study case record forms.

Sample size was calculated by using the formula for

the hypothesis of 2-parallel sample means. In our unit, with the

existing feeding practices, the average time taken by an infant with

birth weight of 1000 to 1500 gram to reach full feeds was 15 days (SD 3

days). We hypothesized that the glycerin suppository group will reach

full feeds by day 12 of life. For a difference of 3 days, with an error

of 0.05 and power 90%, the estimated sample size was 22 in each group.

To account for loss to follow up, 25 infants were to be enrolled in each

group.

Data were analyzed by using IBM SPSS version 18

software. Categorical variables were compared using the Fisher’s exact

test. Continuous measures between groups were compared using two sample

t test or Mann-Whitney U test as appropriate. P value

<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

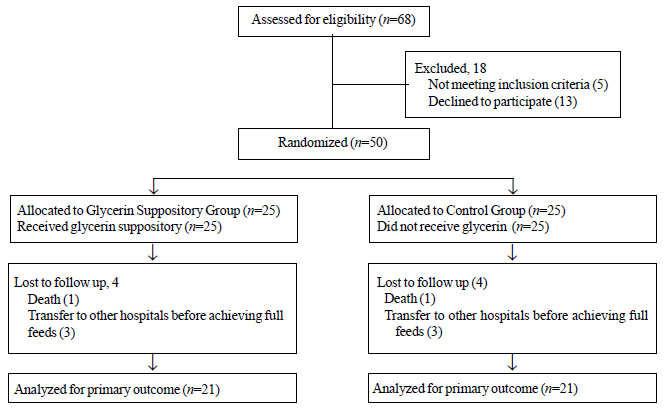

The flow chart of participants in the study is

presented in Fig. 1. A total of 50 infants were

randomized; 25 to glycerin suppository group and 25 to control group.

|

|

Fig.1 Flow of participants in the

study.

|

The baseline clinical and demographic

characteristics of the two study groups were similar (Table I).

Table II depicts the outcomes in the two study groups. The

time required to reach full enteral feeds was similar in both groups.

Glycerin suppository group regained birth weight 2 days earlier than

control group but this difference was not statistically significant. The

age of achieving a weight of 1700 grams, proportion of infants with NEC,

proportion of infants in whom feeds were withheld, and age at discharge

from hospital were similar in both study groups.

TABLE I Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of The Study Participants

|

Characteristic |

Glycerin |

Control

|

|

Suppository

|

Group |

|

Group (n=25) |

(n=25) |

|

Birth weight (g)* |

1179 (142) |

1237 (161) |

|

Gestational age (wks)* |

29.7 (1.3) |

29.7 (1.1) |

|

Males, n (%) |

13 (52%) |

16 (64%) |

|

Antenatal glucocorticoids |

19 (76%) |

20 (80%) |

|

LSCS delivery |

16 (64%) |

14 (56%) |

|

Age at introduction of feeds (d)*

|

5.5 (2.2) |

5.5 (2.8) |

|

Type of milk received |

|

Breast milk only |

18 (72%) |

19 (76%) |

|

Breast milk+Formula milk |

7 (28%) |

6 (24%) |

|

* Values in mean (SD). |

TABLE II Comparison of Outcomes in Glycerine Suppository vs. Control Groups

|

* Outcome

|

Glycerin suppository |

Control group |

Relative risk (95% CI) |

|

group (n=21) |

( n=21) |

|

|

Time to full enteral feeds (d)

|

11.9 (3.1) |

11.3 (3.6) |

0.57 (-1.52 to 2.66) |

|

Time to regain birth weight (d)

|

15.7 (4.1) |

17.1 (1.3) |

-1.45 (-3.35 to 0.45) |

|

Age of achieving weight of 1700 g (d)

|

41.6 (9.7) |

36.3 (8.8) |

5.32 (-0.46 to 11.10) |

|

NEC stage 2 or more, n |

0/21 |

1/21 |

0.33 (0.01 to 7.74) |

|

NEC stage 1, n |

2/21 |

0/21 |

5.0 (0.25 to 98.27) |

|

Feeds withheld, n |

7/21 |

4/21 |

1.75 (0.60 to 5.10) |

|

Duration of hospital stay (d)

|

53.7 (14.4) |

48.9 (14.8) |

4.8 (-4.31 to 13.91) |

|

* Values in mean (SD). |

Discussion

In this randomized controlled trial on 50 VLBW

neonates, we could not detect any difference in time required by the

infant to achieve full enteral feeds in children receiving glycerin

suppository and those not receiving it.

We did not enroll infants <1000 grams in our study

because of perceived risk and difficulty in administering 1g infant

glycerin suppository in this population. The main limitations of our

study was the assessment of only short term outcomes. Moreover, our

study was not powered for outcomes like NEC. We calculated sample size

for 3 days reduction in time required to reach full enteral feeds. A

smaller reduction that may still be clinically meaningful may have been

missed as it requires a large sample size.

Shim, et al. [4], in an observational study,

reported a significant reduction in time to achieve full enteral feeds.

A recent randomized controlled trial by Khadr, et al. [1] showed

that the median time to full feeds was 1.6 days shorter in glycerin

suppository group; however, it was not statistically significant. Haiden,

et al. [6] used gastrografin osmotic contrast for evacuation of

meconium in preterm infants, and observed that the median time to reach

full enteral feedings was shorter in intervention group as compared to

control group. Two systematic reviews evaluating glycerin suppository

for meconium evacuation did not report any benefit on feeding

intolerance or hyperbilirubinemia [16,17]. It may be possible that

glycerin application every 24 hour until complete achievement of full

feeds may be too low to be efficient. A more frequent application (e.g.12

hourly) or higher dose may be more effective in accelerating meconium

evacuation [18]. It is also possible that meconium evacuation cannot be

accelerated by suppositories because rapid and sufficient meconium

passage indicates a correct functionality of the digestive tract.

IIn conclusion, once daily application of glycerin

suppository does not seem to offer any advantage in premature infants in

terms of accelerating achievement of full enteral feeding.

Contributors/i>: SS: review of literature, data

collection and wrote the first draft; NSK: management of patients, study

design, drafting the article, analysis and interpretation of data. He

will act as guarantor; SRS, BSA, JA: management of patients, designing

of study and drafting the manuscript. The final manuscript was approved

by all the authors.

Funding : None; Competing interests:

None stated.

|

What is Already Known?

• Glycerin suppository is useful in early

evacuation of meconium in term and preterm infants.

What This Study Adds?

• DDaily application of glycerin

suppository in preterm infants (gestational age 28-32 weeks)

does not have any advantage in accelerating full enteral

feeding.

|

References

1. Khadr SN, Ibhanesebhor SE, Rennix C, Fisher HE,

Manjunatha CM, Young D, et al. Randomized controlled trial:

impact of glycerin suppositories on time to full feed in preterm

infants. Neonatology. 2011;100:169-76.

2. Leaf A. Introducing enteral feeds in the high-risk

preterm infant. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013:18;150-4.

3. Bisset WM, Watt J, Rivers RP, Milla PJ.

Postprandial motor responses of the small intestine to enteral feeds in

preterm infants. Arch Dis Child. 1989;64:1356–61.

4. Shim SY, Kim HS, Kim DH, Kim EK, Son DW, Kim BI,

et al. Induction of early meconium evacuation promotes feeding

tolerance in very low birthweight infants. Neonatology. 2007;92:67-72.

5. McClure RJ, Newell SJ. Randomised controlled trial

of trophic feeding and gut motility. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed.

1999;80:54-8.

6. Haiden N, Norooz F, Klebermass-Schrehof K, Horak

AS, Jilma B, Berger A, et al. The effect of an osmotic contrast

agent on complete meconium evacuation in preterm infants. Pediatrics.

2012;130:e1600-6.

7. Patole S. Strategies for prevention of feed

intolerance in preterm neonates: a systematic review. J Matern Fetal

Neonatal Med. 2005;18: 67-76.

8. McGuire W, Henderson G, Fowlie PW. Feeding the

preterm infant. BMJ 2004;329: 1227-30.

9. Costalos C, Gounaris A, Sevastiadou S,

Hatzistamatiou Z, Theodoraki M, Alexiou EN, et al/i>.. The effect of

antenatal corticosteroids on gut peptides of preterm infants – a matched

group comparison: corticosteroids and gut development. Early Hum Dev.

2003;74:83-8.

10. Yamauchi K, Kubota A, Usui N, Yonekura T, Kosumi

T, Nogami T, et al. Benign transient non organic ileus of

neonate: Eur J Peditr Surg. 2002;12:168-74.

11. Seigel M. Gastric emptying time in premature and

compromised infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1983:2 Suppl 1;

s236-40.

12. Dimmitt RA, Moss RL. Meconium diseases in infants

with very low birth weight. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2000;9:79-83.

13. Mihatsch WA, Franz AR, Linder W, Pohlandt F.

Meconium passage in extremely low birth weight infants and its

relationship to very early enteral nutrition. Acta Paediatr.

2001;90:409-11.

14. Neu J, Zhang L. Feeding intolerance in very

low-birth weight infants: what is it and what can we do about it? Acta

Paediatr. 2005;94:Suppl.93-9.

15. Bell MJ, Ternberg JL, Feigin RD, Keating JP,

Marshall R, Barton L, et al. Neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis.

Therapeutic decisions based upon clinical staging. Ann Surg. 1978;

187:1-7.

16. Shah V, Chirinian N, Lee S. EPIQ evidence review

Group; Does the use of glycerin laxatives decrease feeding intolerance

in preterm infants? Paediatr Child Health 2011;16:e68-70.

17. Shrinivasjois R, Sharma A, Shah P, Kava M. Effect

of induction of meconium evacuation using per rectal laxative on

neonatal hyperbilirubinemia in term newborn; A systemic review of

randomized controlled trials. Indian J Med Sci. 2010;65:278-85.

18. Emil S, Nguyen T, Sills J, Padilla G. Meconium

obstruction in extremely low-birth weight neonates: guidelines for

diagnosis and management. J Pediatr Surg; 2004; 39:731-7.

|